Gucci has taken a thoughtful, creative approach to engaging Chinese consumers. While other brands have fallen into caricature and suffered for it, Gucci has become a beloved and dominant luxury brand in China.

The Beginning (1997-2014)

In the 1980s, China was still recuperating from the rule of Mao Zedong and the devastating Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) and, due to the government’s strict restrictions on foreign entities, Western brands had achieved little market penetration. Since the 2000s, however, China has produced a new generation of wealthy consumers and now accounts for twenty-eight percent of sales in the luxury market (Kottasová 2018). In 2017, 206 people in China became billionaires—bringing the total to 819 (Chan 2018). A recent global study predicted that Chinese consumers will account for forty-six percent of luxury sales worldwide by 2025 (Hall and Suen 2018). Northwestern University professor Jeffrey Winters explained, “What is happening in China constitutes one of the most rapid emergences of wealth stratification in human history” (Fan 2017).

Under creative director Tom Ford, the Italian fashion house Gucci opened its first Chinese store in 1997 (Blanchard 2012, “Frida Giannini”). As early as 2004, chief executive of the Gucci Group Robert Polet aimed more than sixty percent of its investments towards Asia—particularly China—because he believed that the “Asia Pacific was going to be the big prize to be taken” (“Gucci Learns to Speak Chinese” 2012). Under Polet’s control, the brand went from four to thirty stores in China in ten years. Under the creative direction of Frida Giannini, Gucci organized its first Shanghai fashion show in 2012. Giannini explained, “There is a lot of competition, but we were lucky in that we were already a well-known brand here.” Gucci was so well-known that Giannini would be stopped in the street to have her picture taken as “Frida from Gucci.”

Fig. 1 - Creative Director Frida Giannini (Italian, born 1972). Li Bing Bing for Gucci, 2014. Source: Pursuitist

In 2012, Gucci moved its Chinese headquarters into a state-of-the-art building in the middle of Shanghai and hired Carol Shen as president of Gucci China to manage their 1,500 employees (Blanchard 2012, “Frida Giannini”). At the same time, Chinese actress Li Bingbing was named Gucci’s global spokesperson (Fig. 1), and she declared, “Sometimes I’m a Gucci girl, sometimes I’m a bad girl” (Blanchard 2012, ‘”Li BingBing”). However, Chinese social media followers were not enthusiastic about Li Bingbing’s appearance in Gucci’s advertisements, which were described as “a drunken mess” (Shuang 2015). This would only be the beginning of the new Chinese Gucci generation. Sales declined in 2014 and Gucci had to close six of those Chinese stores.

On a May morning in 2015, loyal Gucci customer Meng Linghao had been waiting since sunrise for the Shanghai Gucci store to open. Fifty others were waiting alongside her to take advantage of Gucci’s latest sale, with discounts up to fifty percent off. Some believed these discounts were related to China’s recent announcement to cut import tariffs to increase domestic consumption; however, a Kering spokesperson countered that the sale was completely unrelated and part of the normal end of the season (Bloomberg 2015). Indeed, Gucci had just reported its weakest quarterly performance in five years and was looking to shift direction by promoting designer Alessandro Michele to creative director, replacing Giannini (Bhasin and Williams 2018). The sale was a business move made by Gucci’s chief executive officer Marco Bizzarri, as an Exane BNP Paribas analyst explained:

“Bizzarri is clearing inventory from the previous collection, as Gucci is looking forward to turning the page on Frida Giannini. Gucci needs a new direction and some correction — I consider this inevitable.” (Bloomberg 2015)

When Giannini was at Gucci’s helm in 2012, she observed that there had been a demand for more classic leather pieces in China instead of a desire for the Gucci logo. She believed, “They want Gucci because it is an international brand, so if I designed something with a more Chinese attitude, I’m not sure they would appreciate it” (Blanchard 2012). This perspective would shift dramatically under Michele.

To Today (2015-Present)

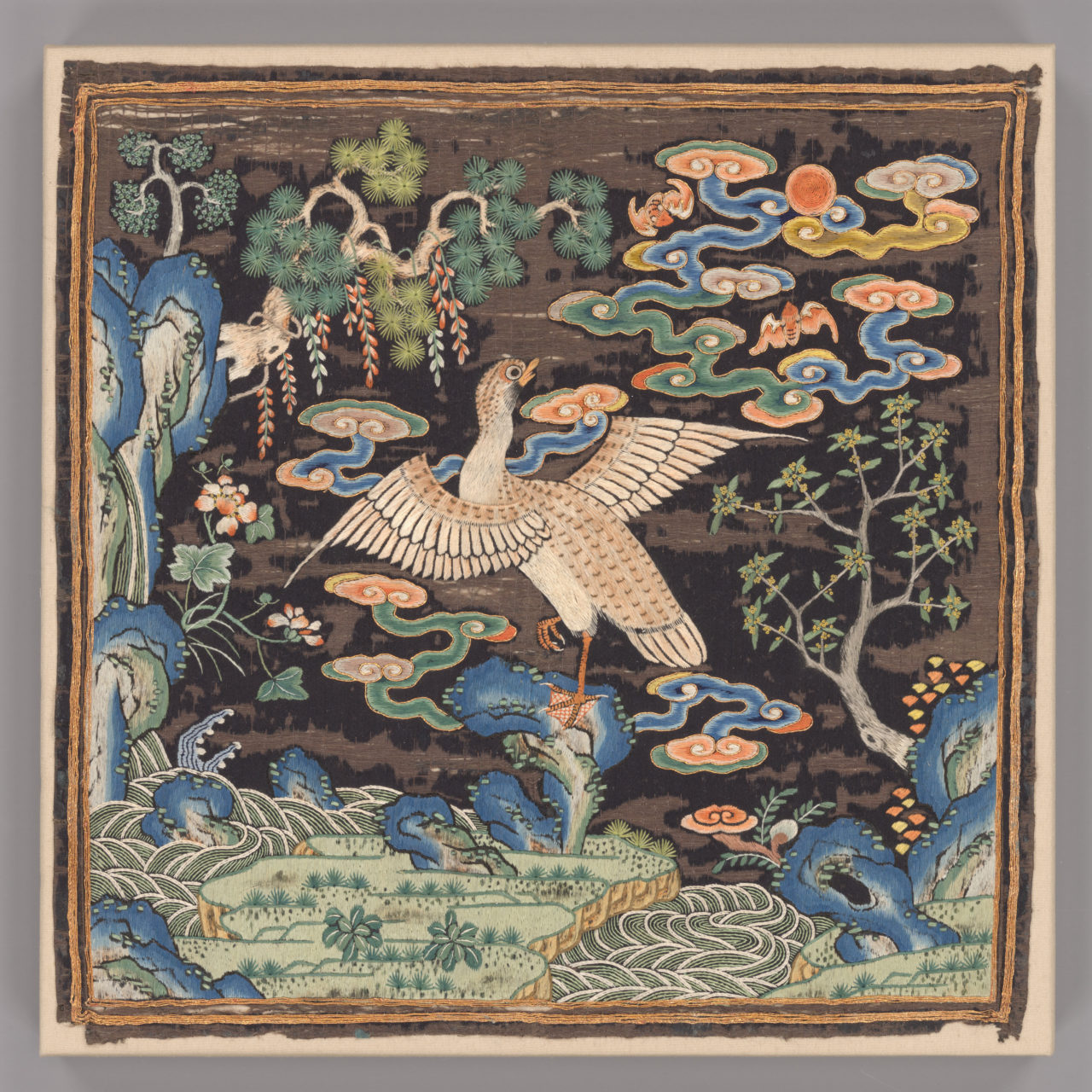

With the help of Asian designers like Cao Fei, Cheng Ran, Kelbin Lei, Yoshito Hasaka and Jaesuk Kim, Gucci created a special print in 2016, called Tian (Fig. 2), which features a floral motif inspired by eighteenth-century Chinese textiles (Fig. 3) (Sauer 2016). They described the print as expressing “the Daoist ideal of harmony with nature, presenting a perfect balance between action and stillness.”

Fig. 2 - Jaesuk Kim (illustrator) (Korean, born 1987). The Gucci Tian print inspired by eighteenth-century Chinese landscapes, Spring 2016. Source: WWD

Fig. 3 - Maker unknown (Chinese, Qing dynasty, 1644–1911). Rank Badge with Wild Goose, 18th century. Silk and metallic thread embroidery on silk satin; 24.1 x 24.1 cm (9 1/2 x 9 1/2 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 30.75.874. Bequest of William Christian Paul, 1929. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

To take advantage of the increased spending on Chinese holidays, Gucci launched capsule collections for Chinese New Year and the Qixi festival. For the 2018 Chinese New Year, the year of the dog, Gucci’s special collection included sixty-three items featuring Alessandro Michele’s own Boston Terriers (Fig. 4) (Derval 2018). For their ready-to-wear-collections, Gucci has continued to incorporate Chinese-inspired elements from fall 2016 to fall 2018. Gucci’s fall 2016 collection even featured in an act of American diplomacy when President Trump and Melania Trump attended state dinner hosted by Chinese President Xi Jinping and his wife Peng Liyuan, who is known as the “master in the art of diplomatic dressing” (Quick 2015). For the Obama’s Chinese state dinner in 2015, Michelle Obama had stunned fashion followers in a black floor-length gown by Chinese-American designer Vera Wang. In 2017 Melania Trump chose Gucci’s interpretation of a qipao (Fig. 5) —a satin floor-length black gown featuring magenta pink cuffs, floral motifs, with a high slit on the side (Fig. 6). Alessandro Michele commented to Robin Givhan, “We have all kinds of customers. Everybody is free to do what they want” (Bryant 2017).

Fig. 4 - Creative Director Alessandro Michele (Italian, born 1972). Gucci's capsule collection celebrating the Chinese New Year, 2018. Photo by Petra Collins. Source: WWD

Fig. 5 - Alessandro Michele for Gucci (Italian, born 1972). Look 30, Fall 2016 Ready-to-Wear. Photograph by Yannis Vlamos. Source: Vogue.com

Fig. 6 - Photographer unknown. US First Lady Melania Trump walks with Peng Liyuan (right), wife of China's President Xi Jinping, in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, November 9, 2017. Photograph courtesy of AFP. Source: The Straights Times

In 2017, Gucci sales skyrocketed to $7.2 billion—a forty-two percent spike, of which thirty percent of sales came from China (Bhasin and Williams 2018). China was Kering’s second fastest-growing market in 2018, and two-thirds of its revenues came from Gucci. Indeed, Helen Brand, executive director of European luxury goods at UBS, declared that while classic labels, like Burberry, were suffering in China, “Gucci is very hot.” Brand continued, “they made sure they have enough entry-level products for millennials like smaller bags and belts …and more than fifty percent of their marketing spending is now on digital” (Kottasavá 2018). Incredibly, in 2018, Gucci’s value increased sixty-six percent to $22.4 billion, which is due in large part to the “Moonlight clans,” China’s millennials who have a love for luxury goods (Bhasin and Williams 2018). Bruno Lannes, a partner at Bain & Company in Shanghai, explained “They don’t have the urge to save … compared to millennials in other countries.” (Kottasavá 2018). In 2018, there are almost sixty Gucci stores across China and the number continues to grow.

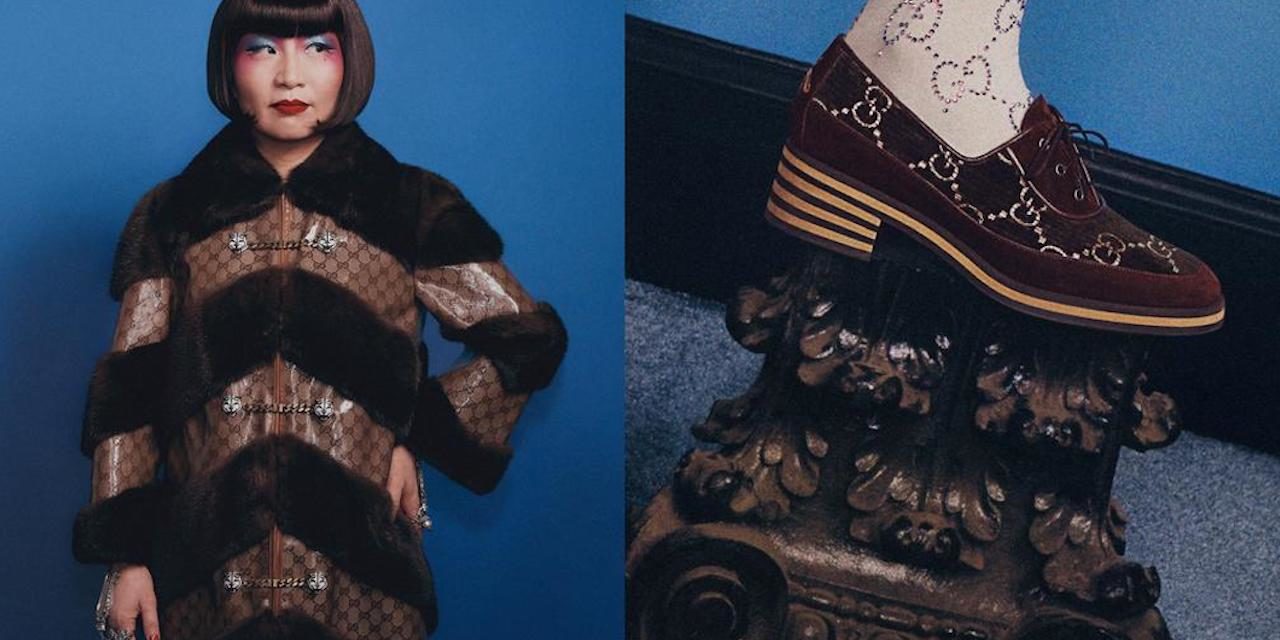

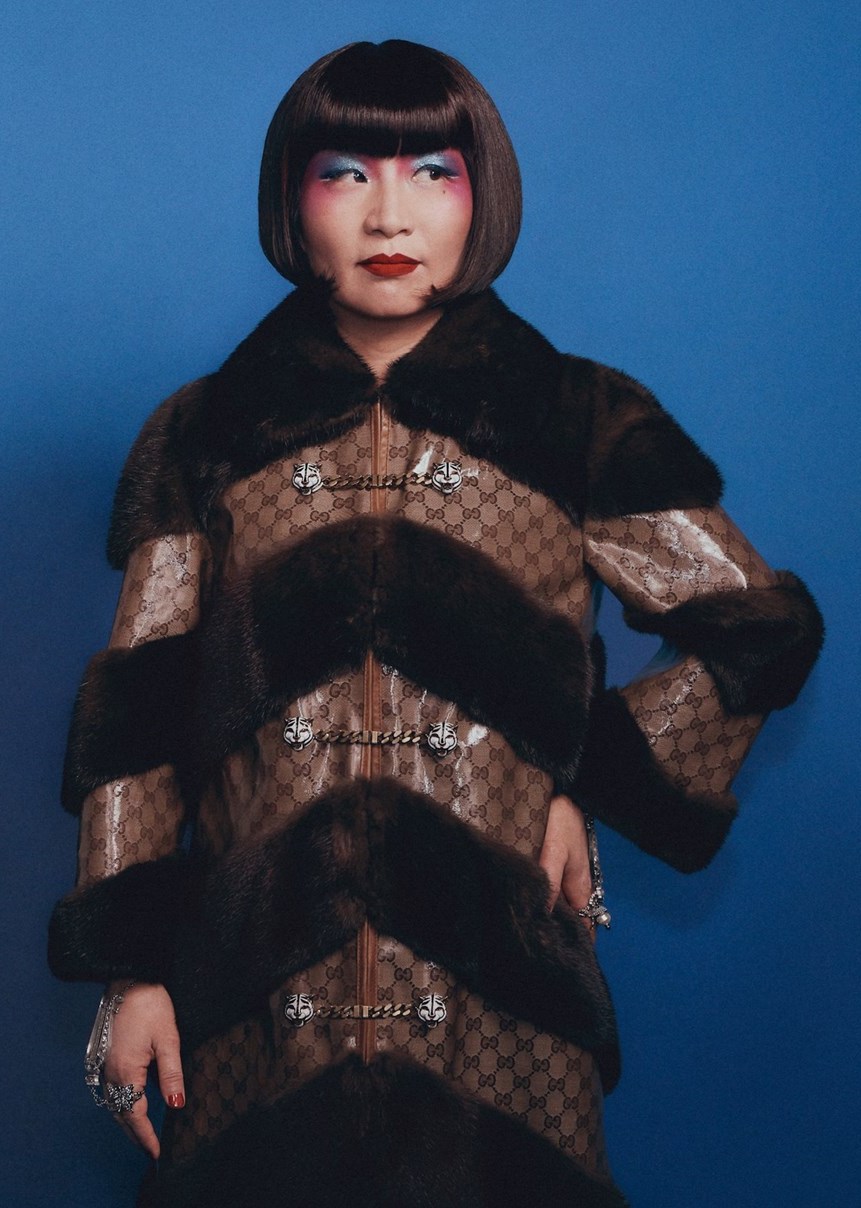

Fig. 7 - Creative Director Alessandro Michele (Italian, born 1972). Zhou Fenxia, a Chinese restaurateur, featured in Gucci’s Cruise 2018 "Roman Rhapsody" campaign, 2017. Photo by Mick Rock. Source: Gucci

Western brands are realizing the importance of Chinese digital and social media platforms, with nine percent of sales in China coming from e-commerce (Hancock 28). Gucci launched its new online shop in China last year, which is the only place where their products are sold online in the country. While brands like Burberry, Tiffany, Saint Laurent, and Alexander McQueen utilize Alibaba and JD.com, two other popular e-commerce platforms in China, Gucci has decided to stay away due to the rampant counterfeiting on such platforms. Bizzarri also believes that joining those platforms would lessen the sense of exclusivity necessary to sustain a luxury brand. Gucci does, however, have a presence in the Chinese digital sphere via WeChat, a platform they used to create three small programs for customers to interact digitally with the brand. “Gucci Gucci” is featured on WeChat’s main page, which reflects the high-end style of the brand. Second, “Gucci beauty self-expression” allows users to take pictures and add Gucci design elements to their photos. The third is a section where customers can purchase gift cards to increase spending (“What Are Gucci’s 3 Marketing Strategies in China?” 2018).

Gucci has also partnered with many Chinese key opinion leaders, or KOLs. These internet celebrities have a large number of followers and access to a younger Chinese generation, which means even more promotion for the brand. Last year Gucci partnered with Gogoboi, a Chinese fashion KOL, to launch his holiday collection, which sold out in five days. Gucci has collaborated with other KOLs such as Chinese pop singer LiYu Chun, restaurant owner Zhou Fenxia (Fig. 7), and actress Ni Ni to market to different types of Chinese clientele (“What Are Gucci’s 3 Marketing Strategies in China?” 2018). Gucci’s Western social media platforms also frequently feature Chinese models and celebrities, who often appear in Gucci advertisements, special events, and shows (Fig. 8). All of these strategic moves have proved to be successful ones, reaffirmed by Women’s Wear Daily’s recent report that named Gucci the top brand in Chinese social media, according to “mentions, reports, likes, reads, sentiment, purchase intent and total engagement” (Zaczkiewicz 2016).

Fig. 8 - Gucci. Chinese celebrity Ni Ni featured on Gucci’s Instagram and Gucci eyewear campaign, October 4, 2018. Source: Instagram/Gucci

While Gucci has been prospering in the Chinese market, some brands have had the opposite of success. To promote an upcoming runway presentation in Shanghai in 2018, Dolce & Gabbana caused an uproar when a video posted on the brand’s Weibo account featured an Asian model struggling to eat Italian food with her chopsticks. Viewers deemed it racist and stereotypical, which led the brand to delete the video. This controversy took a turn for the worse when derogatory comments were made about the Chinese by D&G co-founder Stefano Gabbana on Instagram. Dolce & Gabbana claimed that Gabanna’s account, as well as the brand’s, were hacked. While the two designers did issue a public apology, Gabbana’s direct messages were widely shared on Chinese social media, prompting the trending hashtag #BoycottDolce. Due to the public fury and protests, the show was canceled, reportedly by Chinese authorities.

In comparison, Gucci has taken a step further in incorporating China into their marketing initiatives. For example, to promote their pre-fall 2018 collection, Gucci collaborated with Vogue to create a photo shoot featuring six Shanghainese families, including a young couple, a Chinese doctor, and twin sisters (Fig. 9, 10). Each group wore their favorite items from the collection and posed around Shanghai. The brand has also created special items that fit the Asian body type. Shawqi Ghanem, Managing Director of Grand Optics explains:

“Brands like Gucci develop products specifically for the Asian market, with a special nose bridge style, and specific designs for the front of the sunglasses, that fit the Asian face.” (Derval 2018)

Gucci has also incorporated floral prints and more feminine elements for their men’s collections to attract the Chinese male customer, who tend to embrace more feminine elements in their wardrobe than the men in the West. Gucci has learned to embrace—not caricature—Chinese culture, while sharing it globally with all of their customers. This is a respectful model that treats China as China, which many designer brands can learn from.

References:

- “25 Ways to Gucci: Shanghai’s Style Remix.” Vogue. September 13, 2018. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://www.vogue.com/article/25-ways-to-gucci-shanghai-street-style.

- Bain, Marc. “How Much Do Top Fashion Brands Really Depend on China?”Quartz. August 21, 2015. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://qz.com/484013/how-much-do-top-fashion-brands-really-depend-on-china/.

- Bhasin, Kim, and Robert Williams. “Gucci Strikes China Gold, Thanks to ‘Moonlight Clans’ Who Spend It All.” Bloomberg.com. May 29, 2018. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-05-29/gucci-strikes-china-gold-thanks-to-moonlight-clans-who-spend-it-all.

- Blanchard, Tamsin. “Frida Giannini: Gucci’s Shanghai Express.” The Telegraph. November 13, 2012. Accessed November 30, 2018. http://fashion.telegraph.co.uk/news-features/TMG9674484/Frida-Giannini-Guccis-Shanghai-express.html.

- Blanchard, Tamsin. “Li Bingbing: Gucci’s Chinese Torchbearer.” The Telegraph. April 23, 2012. Accessed November 30, 2018. http://fashion.telegraph.co.uk/news-features/TMG9221059/Li-Bingbing-Guccis-Chinese-torchbearer.html.

- Bloomberg. “With Chinese Discounts, Gucci Turns the Page on Frida Giannini.” The Business of Fashion. May 27, 2015. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/news-analysis/with-chinese-discounts-gucci-turns-the-page-on-frida-giannini.

- Bryant, Kenzie. “Melania Trump Wears a China-Themed Gucci Dress to State Dinner in Beijing.” The Hive. November 09, 2017. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2017/11/melania-trump-china-state-dinner-gucci.

- Chan, Tara Francis. “Communist China Has 104 Billionaires Leading the Country While Xi Jinping Promises to Lift Millions out of Poverty.” Business Insider. March 02, 2018. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://www.businessinsider.com/billionaires-in-china-xi-jinping-parliament-income-inequality-2018-3.

- DeHart, Jonathan. “China’s Nouveau Riche: Truth Exceeds Fiction.”The Diplomat. June 13, 2013. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://thediplomat.com/2013/06/chinas-nouveau-riche-truth-exceeds-fiction/.

- Derval, Diana, Dr. “How Gucci Won China over.” LinkedIn. October 3, 2018. Accessed November 29, 2018. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/how-gucci-won-china-over-prof-diana-derval-戴安娜.

- Fan, Jiayang. “China’s Rich Kids Head West.” The New Yorker.June 19, 2017. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/02/22/chinas-rich-kids-head-west.

- “Gucci Learns To Speak Chinese.” Jing Daily.April 11, 2012. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://jingdaily.com/gucci-learns-to-speak-chinese/.

- Hall, Casey, and Zoe Suen. “Luxury Brands Need to Invest in Chinese Teens.” The Business of Fashion. November 21, 2018. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/professional/luxury-brands-need-to-invest-in-chinese-teens-balenciaga-gen-z.

- Hancock, Tom. “Gucci Wary of Chinese Ecommerce Tie-up Because of Fakes.” Financial Times. October 15, 2018. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://www.ft.com/content/5d75fe48-d05d-11e8-a9f2-7574db66bcd5.

- Kottasová, Ivana. “Chinese Shoppers Can’t Get Enough Luxury.” CNN. October 04, 2018. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://www.cnn.com/2018/10/04/business/china-economy-luxury-brands/index.html.

- Paton, Elizabeth. “The Great Promise of China.”The New York Times. November 19, 2018. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/19/fashion/china-luxury-retail.html.

- Quick, Harriet. “Mrs Peng – a Master in the Art of Diplomatic Dressing.”The Telegraph.October 21, 2015. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/11946175/Mrs-Peng-a-master-in-the-art-of-diplomatic-dressing.html.

- Sauer, Abe. “#GucciGram: Gucci Tian Prints Target Luxury Buyers in China.”Brandchannel:. March 31, 2016. Accessed December 01, 2018. https://www.brandchannel.com/2016/03/31/gucci-tian-china-033116/.

- Shuang, Tang. “Op-Ed | How Celebrity Sells in China.” The Business of Fashion. January 27, 2015. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/opinion/op-ed-celebrity-sells-china.

- “What Are Gucci’s 3 Marketing Strategies in China ?”Marketing to China.October 05, 2018. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://www.marketingtochina.com/gucci-marketing-strategy/.

- Zaczkiewicz, Arthur. “Gucci Named Top Brand in Study of Social Media Influencers.” WWD. September 01, 2016. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://wwd.com/fashion-news/designer-luxury/gucci-top-social-media-brand-10519420/.