Flappers and mods rebelled against the traditional image of femininity held by the generations before them. Although their worlds were very different, their fashion and beauty ideals were remarkably similar.

Introduction

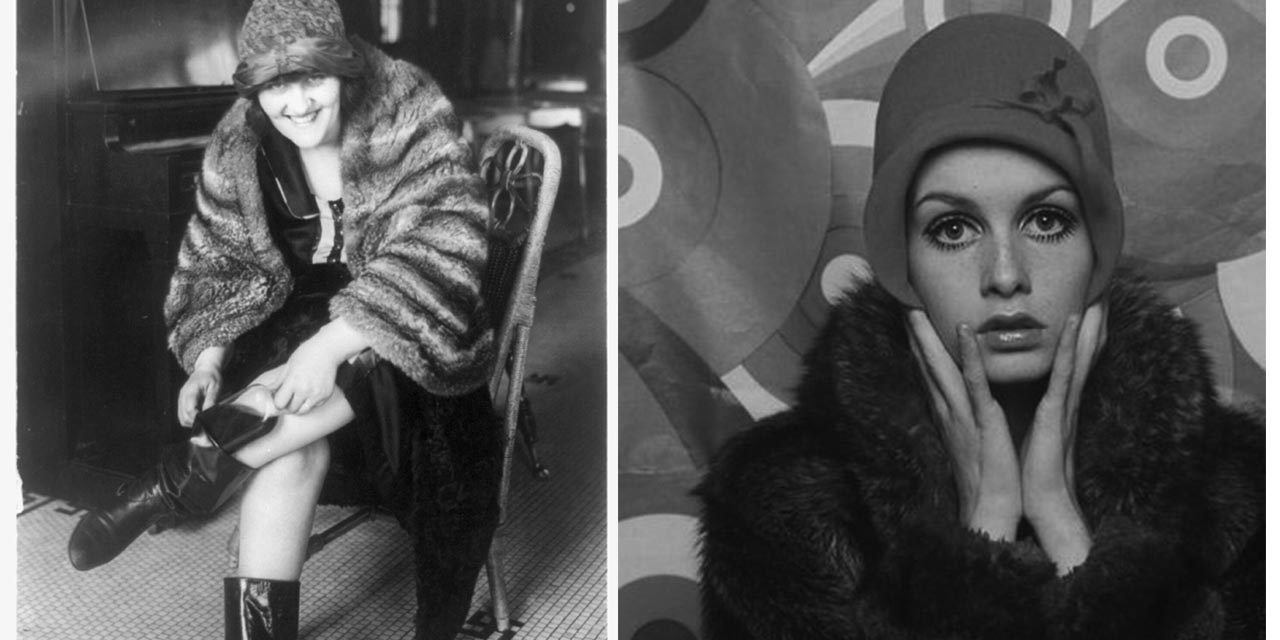

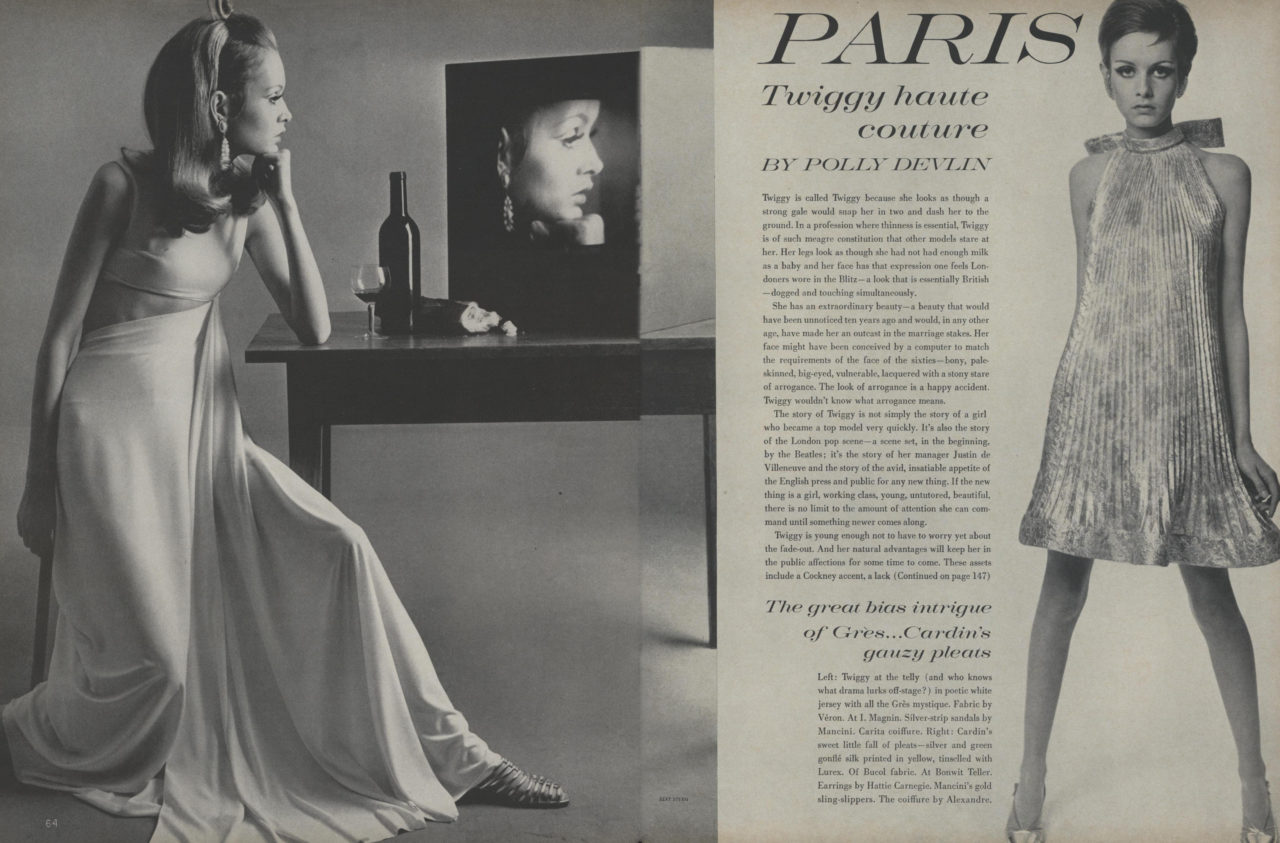

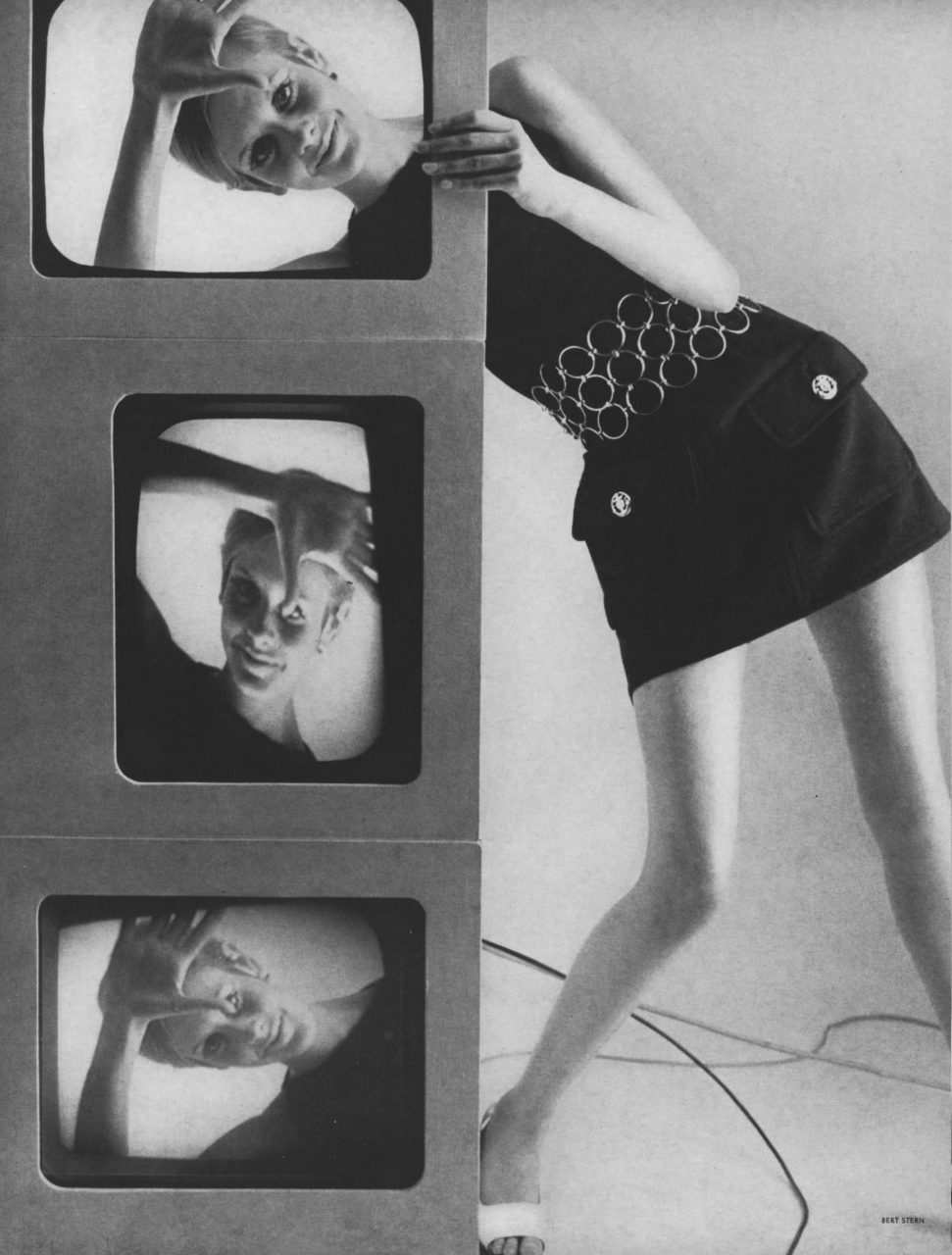

I n a 1967 issue of Vogue, Polly Devlin wrote about the appearance of fashion model Twiggy – something she perceived to be an unprecedented phenomenon (Fig. 1). She felt that in any other period of history, Twiggy’s beauty would not only have gone “unnoticed” – she would have been “an outcast in the marriage stakes” (Devlin 65). Among her physical qualities that were supposedly unique to the sixties were her big eyes and overall boniness (Devlin 65). It is inarguable that Twiggy’s level of fame as a fashion model in the mid-1960s was historically unprecedented; however, Devlin was incorrect to state that her traits were totally unique to the decade (Gibson). Many of Twiggy’s physical traits and typical costume, which were examples of the British mod style tribe, were also ideal among the flapper youth subculture of the 1920s (Fig. 2). Though they existed four decades apart, during radically different times, they shared many fashionable ideals. Flappers and mods both reflected the revolutionary movements, social progress, and changing gender roles of their times – which were manifested in remarkably similar ways. Both groups idealized thin, flat bodies and short, boyish hair, wore shockingly short clothing, eye-enhancing cosmetics, and were obsessed with music. In addition, both youth subcultures were criticized by their elders and the press; however, in the end, many of their characteristics were assimilated into mainstream culture.

Fig. 1 - Bert Stein (American, 1929-2013). Twiggy Haute Couture, March 1967. Source: Vogue

Fig. 2 - Jean-Claude Sauer (French, 1935-2013). Twiggy, 1965. Paris: Paris Match Archive, M0161619. Source: Paris Match

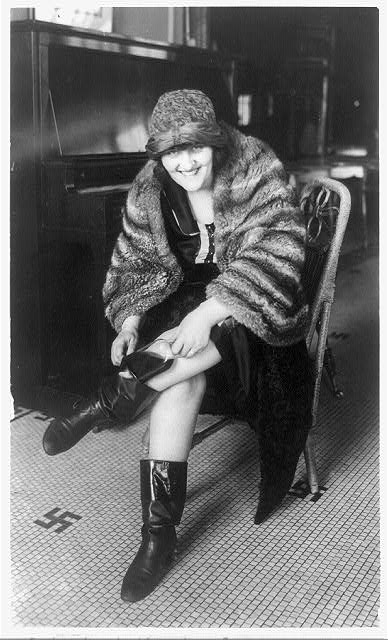

Fig. 3 - Photographer unknown. Flapper putting a flask in her boot, January 1922. Photographic print. Washington, D.C.: National Photo Company Collection, LOT 12294, vol. 1, p. 25. Source: The Library of Congress

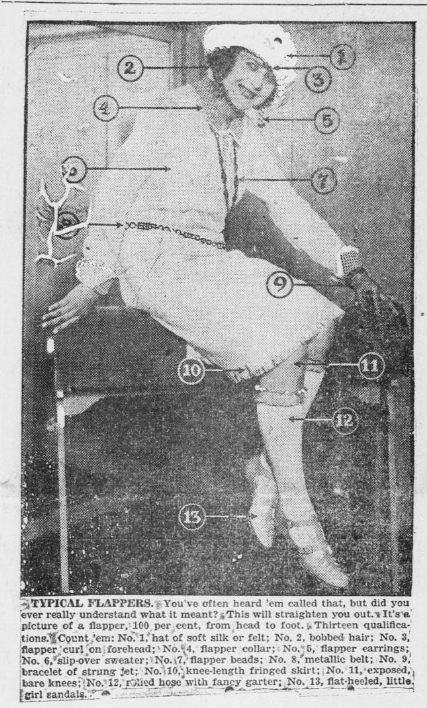

Fig. 4 - Unknown. Typical Flappers, August 1922. Prescott, AZ: Weekly Journal-Miner, No. 26779. Source: The Library of Congress

Fig. 5 - MGM. Lobby card for the American drama film Our Dancing Daughters, 1928. Watercolor and ink on board; (11" x 14" in). Source: Wikimedia Commons

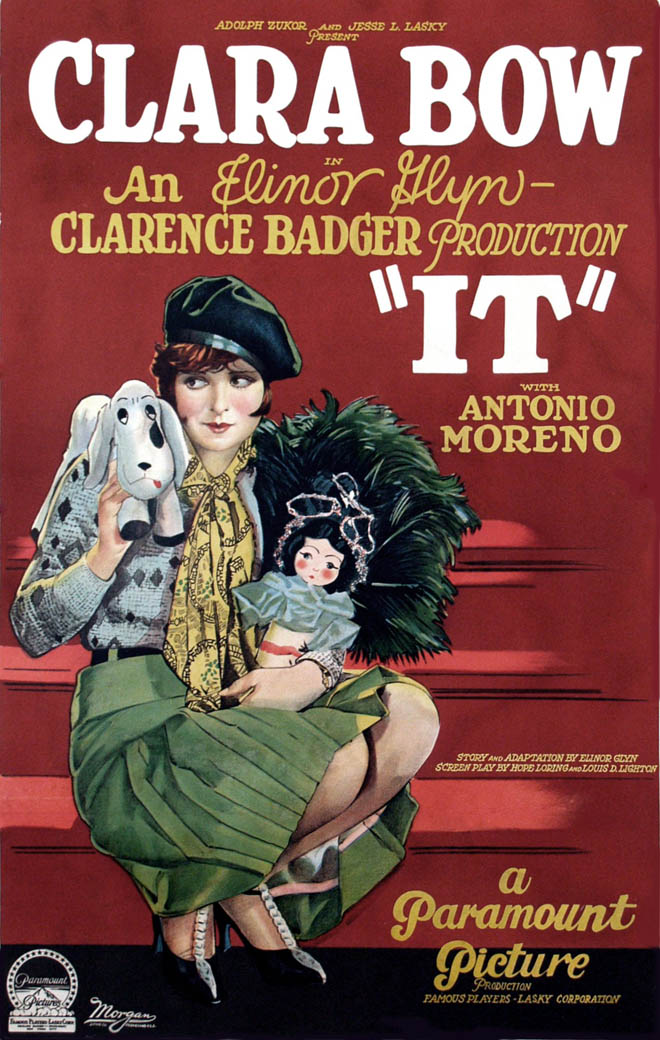

Fig. 6 - Paramount Pictures. Theatrical release poster for It., 1927. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Background: Flappers & Mods

T he 1920s arrived on a seismic wave of social change and economic prosperity, which directly resulted in the advent of “flapper” girls. Young women celebrated unprecedented rights, including suffrage, increased access to education, and more opportunities to work outside the home (Breunig). Restrictive corsets, cumbersome hemlines, and unstable hairstyles were ill-suited for the lifestyles of “fast living” working girls of the twenties (Sauro). As a result, some young women rebelled against fashionable society, and gave a new meaning to the word “flapper” (Moffitt). The term has a long history, and in the nineteenth century referred to a “flighty or hoydenish adolescent girl” (Sauro). One 1917 Vogue article explained that flapper was a stigmatized word to describe a young girl at a “difficult” or “awkward” age (“Fashion: The Term ‘Flapper’ Carries No Stigma”). However, in the post-WWI era, the term came to refer to this novel brand of rebellious adolescent girl, who exemplified new gender ideologies (Fig. 3) (Moffitt). Flappers were working-class girls, and their ensembles frequently violated the prevailing etiquette of fashion (Sauro). They cut their hair, shortened their skirts, and they rolled down their stockings (Fig. 4). The flapper was also referred to by contemporaries as “garçonne, bachelor girl, business girl, girl scout and vamp,” – but she referred to herself as “modern” (Wollstein; “Want Flapper Called ‘Modern’; Camp-Fire Girls War on Term”).

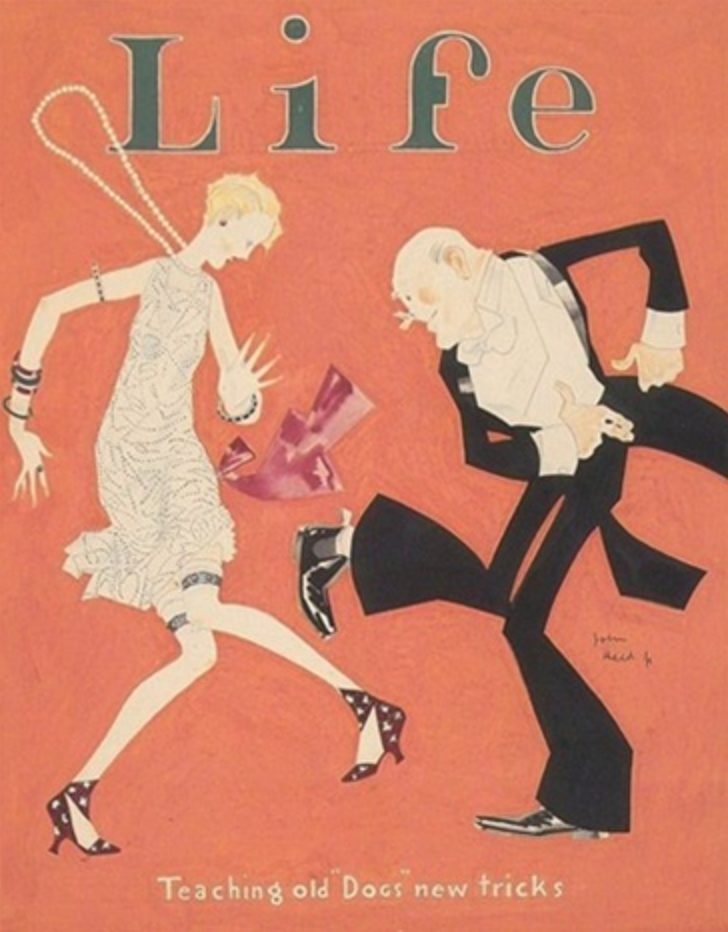

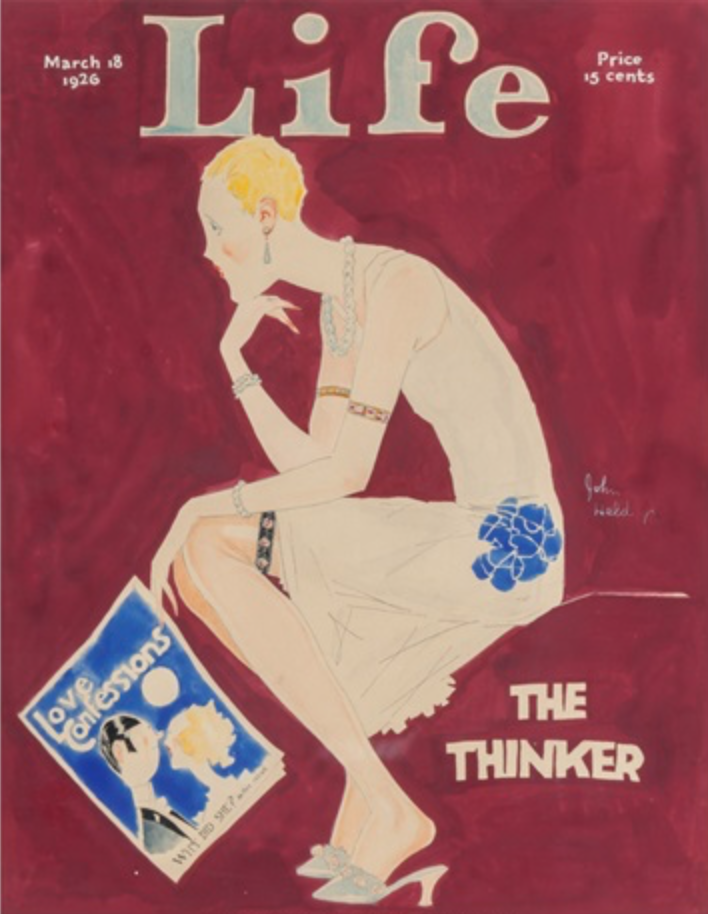

What began as a youth subculture transformed into a larger-than-life pop culture figure through literature, illustrations, and Hollywood films. Cartoonist John Held Jr. is widely credited with establishing the popular image of the flapper through his illustrations, which were circulated in Life, Judge, College Humor, and The New Yorker (Figs. 7-9) (“John Held Jr., Cartoonist, Dies; Satirist of the Twenties Was 69”). In his cartoons, Held depicted the flapper as flippant, unsophisticated, and string-bean-like in appearance (Moffitt). His work can also be found alongside that of F. Scott Fitzgerald, a prominent American author now regarded as the “spokesman of the Jazz Age” (“Fitzgerald, F. Scott”). Fitzgerald attempted to capture the spirit of the flapper in his works Flappers and Philosophers (1920), Tales of the Jazz Age (1922), and The Great Gatsby (1925). In glamorous films, flappers were portrayed by young Hollywood stars Clara Bow, Colleen Moore, Anita Page, and Joan Crawford (Figs. 5-6). The costumes worn by flappers in films like Our Dancing Daughters (1928) cannot be mistaken for the dress of real, working-class flapper girls. They did, however, serve as style inspiration for some wealthier film-goers. Such films helped proliferate the popular image of the flapper as jazz-loving but highly fashionable.

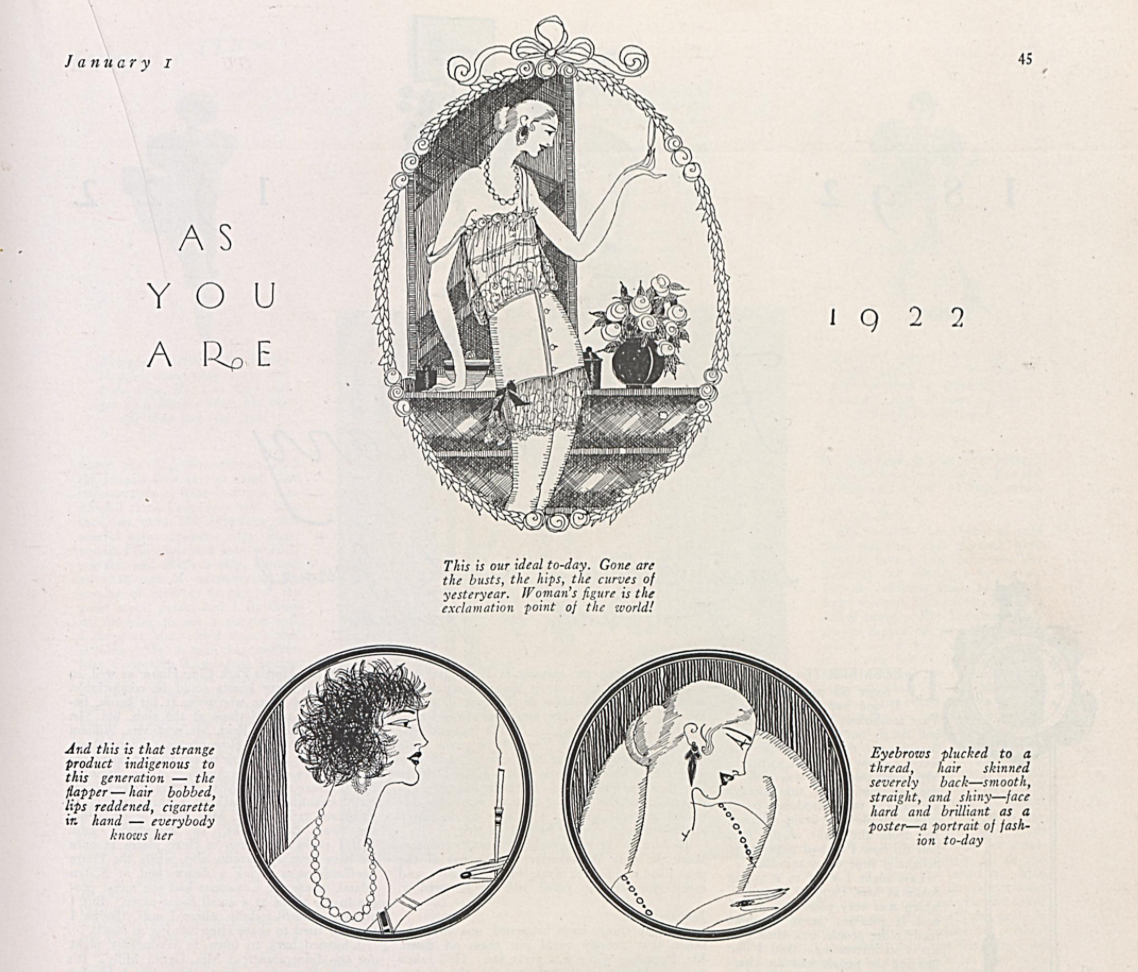

On the screen and the streets, flappers were met with confusion, concern, and even severe scrutiny by the general public. While some girls simply aligned with the physical appearance of flappers, a more daring breed engaged in taboo activities such as drinking, smoking, and promiscuity (Wigmore et al.). Juxtaposed with a portrait of the ideal fashionable woman, a 1923 Vogue article labeled the shaggy-haired flapper “that strange product indigenous to this generation” (“Fashion: As You Are, 1922”). In 1924, the New York Times described flappers as “an entirely different specimen from anything ever known before in the history of the species female, normal or otherwise” (Wollstein). Although the flapper’s behavior was scandalized by the press, some felt it was simply a passing fad, with no real cause for concern (“Defends Flapper as a Normal Girl: Secretary of Labor Davis In Mother’s Day Address at Arlington Sees Her Future Sure”). Indeed, in 1928 the young ladies of The Junior League Magazine officially declared the flapper deceased – but saw no issue speaking ill of the dead (Wigmore et al.). Bidding her good-riddance, they proceeded to ridicule everything about the flapper’s appearance and mannerisms.

Fig. 7 - John Held Jr. (American, 1889-1958). Flapper and sugar daddy dancing (illus. for Life), 1926. Watercolor and gouache; (15.75 x 12.25 in). Source: Artnet

Fig. 8 - John Held Jr. (American, 1889-1958). The Thinker, Life magazine cover, 1926. Watercolor and ink on board; (13.5 x 10.5 in). Source: Artnet

Fig. 9 - John Held Jr. (American, 1889-1958). "Kamerad!" Cover illustration for The American Legion Weekly, 1926. Gouache, pen and ink on thick paper; (9.3 x 8 in). Source: Artnet

Not unlike the 1920s, the 1960s were also a revolutionary period which engendered a “youthquake” of fashion subcultures. The sixties are intrinsically linked with historic moments, social movements, and political upheavals – all of which were vastly influential on youth. The sexual revolution was especially impactful for young women, who were embracing more sexually liberated lifestyles. The atmosphere of revolution, economic prosperity, and a musical renaissance contributed to burgeoning street style and style tribes. Among the earliest youth style tribes of the sixties were the “mods” (Figs. 10-11). The style, short for “modernist,” originated in late 1950s on the streets of London (see Figure 5) (Divita). From the beginning, mods were at odds with another youth style tribe, the “rockers” (Laurie 68). They were eventually joined by the “hippies” around 1966 (Tortora & Marcketti).

Many aspects of the mod subculture differ from that of the flappers, yet there are interesting parallels. Like flappers, mods were working-class teenagers filled with contempt towards adults (Laurie 68). However, one major difference is that mods were a co-ed subculture group in which men featured prominently. Perhaps the largest distinguishers between the two lie in their attitudes. Mods saw themselves as highly sophisticated and self-restrained, refraining from boastfulness, aggression, and overt sexuality (Laurie 69). In addition, they took great pride in their appearance and possessions. Motor scooters, like Vespas, were very important to mod culture (Laurie 68). However, clothing was the mod’s greatest obsession, and their styles were rapidly changing (Jenss). Mods constantly desired originality in their dress, which became an issue when the mod style was brought abroad and became mainstream.

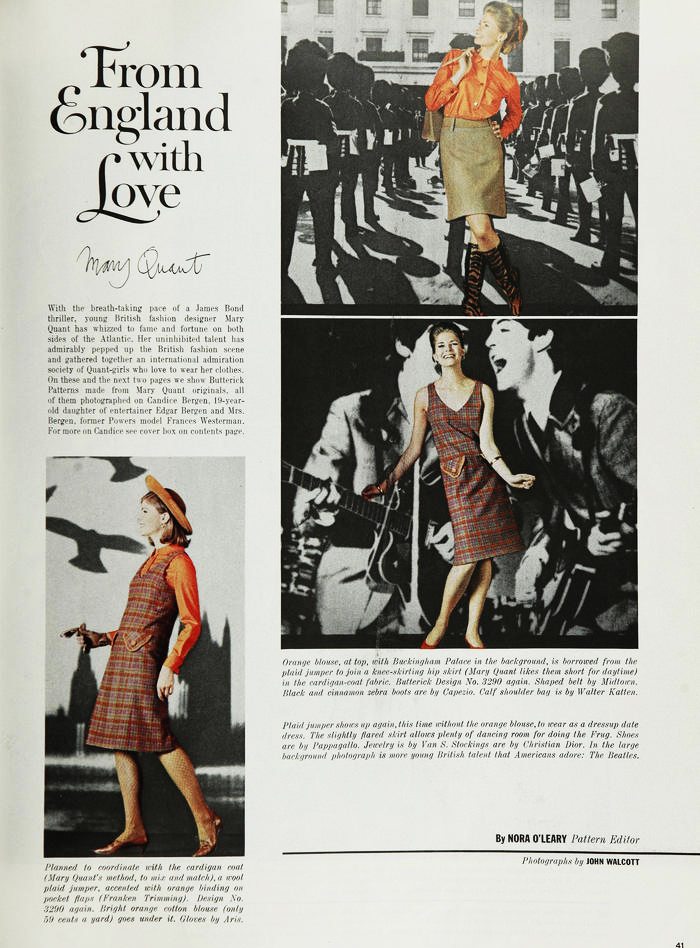

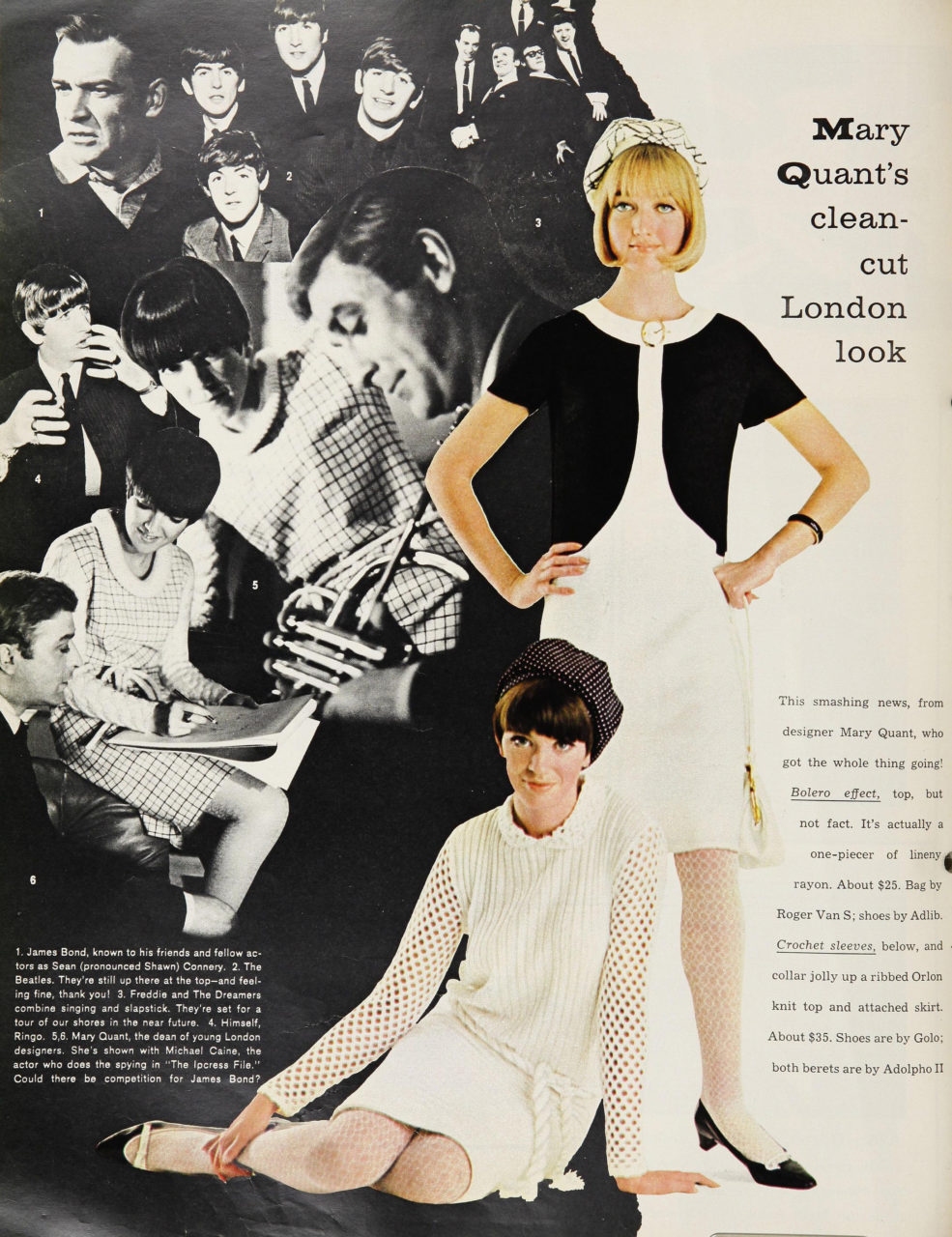

Just as the flapper’s image was transformed by media and assimilated into the mainstream, as was the mod subculture. In 1955, Mary Quant opened a shop in London called Bazaar where she sold her youthful, mod-inspired fashion designs (de la Haye). By 1962, Quant was spreading her designs throughout the United States (Fig. 12) (de la Haye). For many young Americans, it was Mary Quant and The Beatles who put both London and mod fashion on the map (Fig. 13). In fact, magazines even displayed Quant’s designs against a Beatles photo backdrop (Fig. 14-15). Other notable designers associated with mainstream mod fashions include André Courrèges and Pierre Cardin (Steele 49-76). Even as early as 1965, Women’s Wear Daily declared that mods and The Beatles were among the biggest fashion influences of the decade (“The ‘60s: When Women Made the Fashion”). Then, as the “Face of ’66,” fashion model Twiggy embodied the “quintessence of the London image,” which in the United States had become synonymous with mod (Fig. 16) (“Twiggy”; Divita). In a way, Twiggy became to the original mods what Held’s illustrations were to flappers: a glamorized, commercialized caricature of a once-alternative youth subculture.

Fig. 10 - Caxton Youth Trust. Group of Mod girls from Caxton Mod Club, 1960s. London, UK: Museum of Youth Culture. Source: Google Arts & Culture

Fig. 11 - Roger Mayne (British, 1929-2014). Mod girls in Brixton, 1966. Paper. Museum of London, IN15292. Source: Museum of London

Fig. 12 - Associated Press. Three models and designer Mary Quant wearing her mod fashions in Little Rock, Arkansas., October 1968. London, UK: Museum of Youth Culture. Source: Pop Culture Universe: Icons, Idols, Ideas, ABC-CLIO

Fig. 13 - Photographer unknown. The Beatles, 1967. Washington D.C.: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-122935. Source: Library of Congress

Fig. 14 - John Walcott. From England with Love, August 1964. Source: Ladies' Home Journal

Fig. 15 - Photographer unknown. Mary Quant's Clean-Cut London Look, March 1965. Source: Seventeen

Fig. 16 - Bert Stein (American, 1929-2013). Twiggy on the tube, March 1967. Source: Vogue

Shared Fashionable Ideals

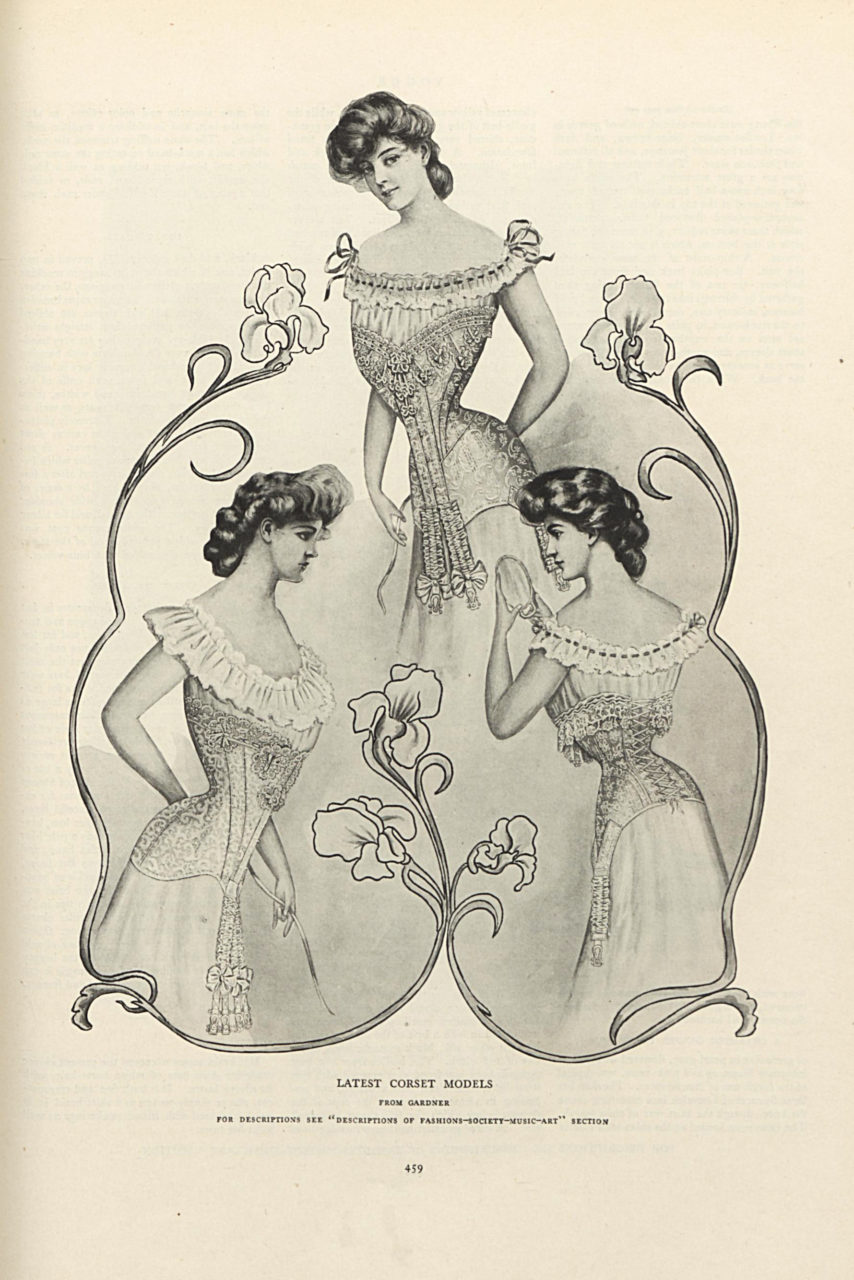

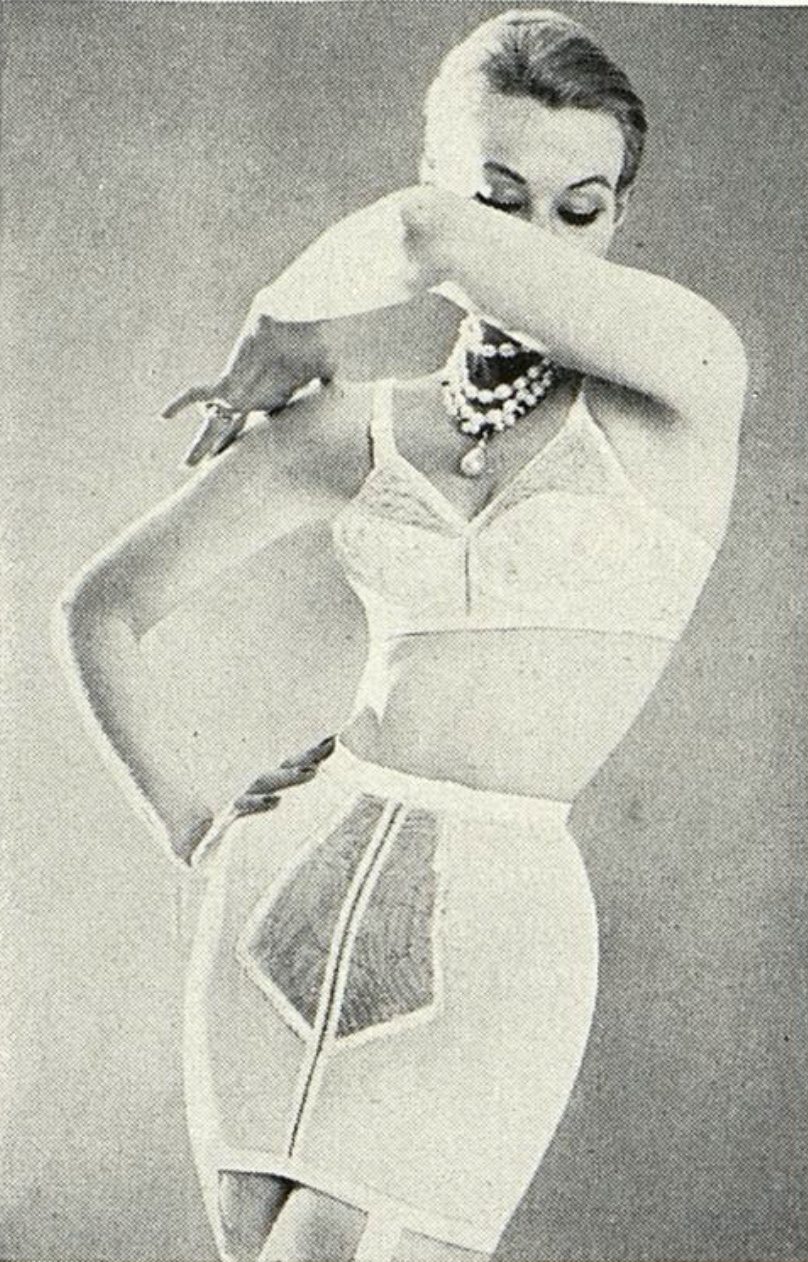

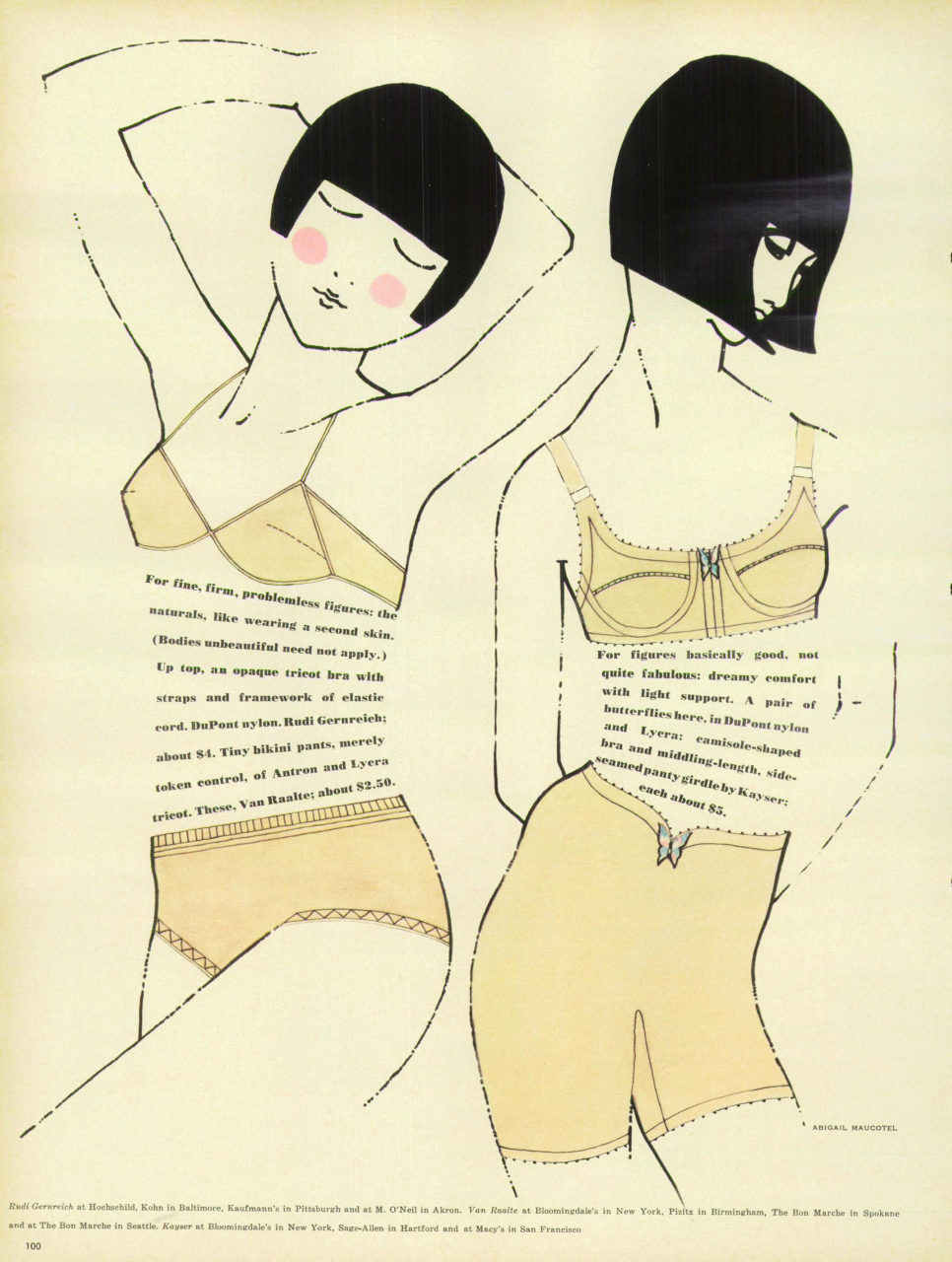

B oth the flapper and the mod idealized a narrow, slim body, in direct opposition to that of the generation before her. Much has been written about the stark physical contrast between the 1920s flapper girl and Charles Dana Gibson’s “Gibson Girl,” who exemplified the ideal young woman of the 1890s (Gianoulis). The famous “S” shape of the Gibson Girl’s body was achieved through corsetry and padding (Fig. 17) (Gianoulis). However, in January of 1923, Vogue declared: “Gone are the busts, the hips, the curves of yesteryear” (“Fashion: As You Are, 1922”). In another Vogue article, the author laments that while anyone could achieve the figure of a Gibson Girl through artifice, “it really seems as if none but the emaciated could get into” the straight silhouette of the 1920s (Fig. 18) (Hillis). In the post-WWII era, the feminine hourglass figure was once again ideal. A 1953 Cosmopolitan feature on Marilyn Monroe partially attributed her success to her “staggering set of measurements” (Heilbroner). In the 1950s, a figure expertly molded by foundation garments was crucial for the fashionable figure (Fig. 19) (“The Fitter is a Girl’s Best Friend”). However, in the 1960s many teens idealized Twiggy, who essentially had no figure at all. One 1967 Vogue article warned readers of a dangerous trend in “Twiggy-inspired” dieting among young school girls who desired the “Twiggy figgah” (“Beauty Checkout: Automatic Lift/The Twiggy Figgah…”). Lightweight foundation garments were marketed towards teenaged girls, and emphasized the “natural look,” rather than the ultra-feminine hourglass (Fig. 20).

Fig. 17 - Gardner. Latest Corset Models, April 1904. Source: Vogue

Fig. 18 - Marguerite Ohman. The Changing Silhouette, November 1928. Source: Ladies' Home Journal

Fig. 19 - Karlson. New Line Formation, October 1957. Source: Harper's Bazaar

Fig. 20 - Abigail Maucotel. New Shapes of Fashion, October 1965. Source: Seventeen

Short hair was ubiquitous among flappers, and was also common among mod girls. One of the greatest visual distinguishers of the flapper was her hair – or lack thereof (Fig. 21). In the back, her hair was cut into a “too short shingle,” putting her neck on full display (Wigmore et al.). She may have had bangs and some length at the sides, forming a “youthful bob” (“Features: The Crowning Glory of Youth”). The flapper’s bob also broke from the past in that it was straight rather than curly. The “youthfulness” and “practicality” of the bob caused it to spread throughout fashionable society, eventually becoming de rigueur for all “smart women” (“Features: Short Cuts to Chic”). While it eventually fell out of style in the ensuing decades, a similar hairdo was seen on mod girls of the 1960s. The short hairstyle is permanently associated with Twiggy, and she admits receiving the cut was what propelled her modeling career (Fig. 22) (“Twiggy by Twiggy” 106). However, years before Twiggy entered the scene, some mod girls “razor-cut their hair close to the head and down the neck like a boy’s,” (Fig. 23) (Laurie 68). As mod culture became more mainstream, many may have adopted the “Sassoon” haircut inspired by Mary Quant or The Beatles (“Hairdos Of The Month”; “Beatlemania U.S.A.”). However, unlike with flappers, the short cut was not ubiquitous among mods. Some mods would wear their hair long.

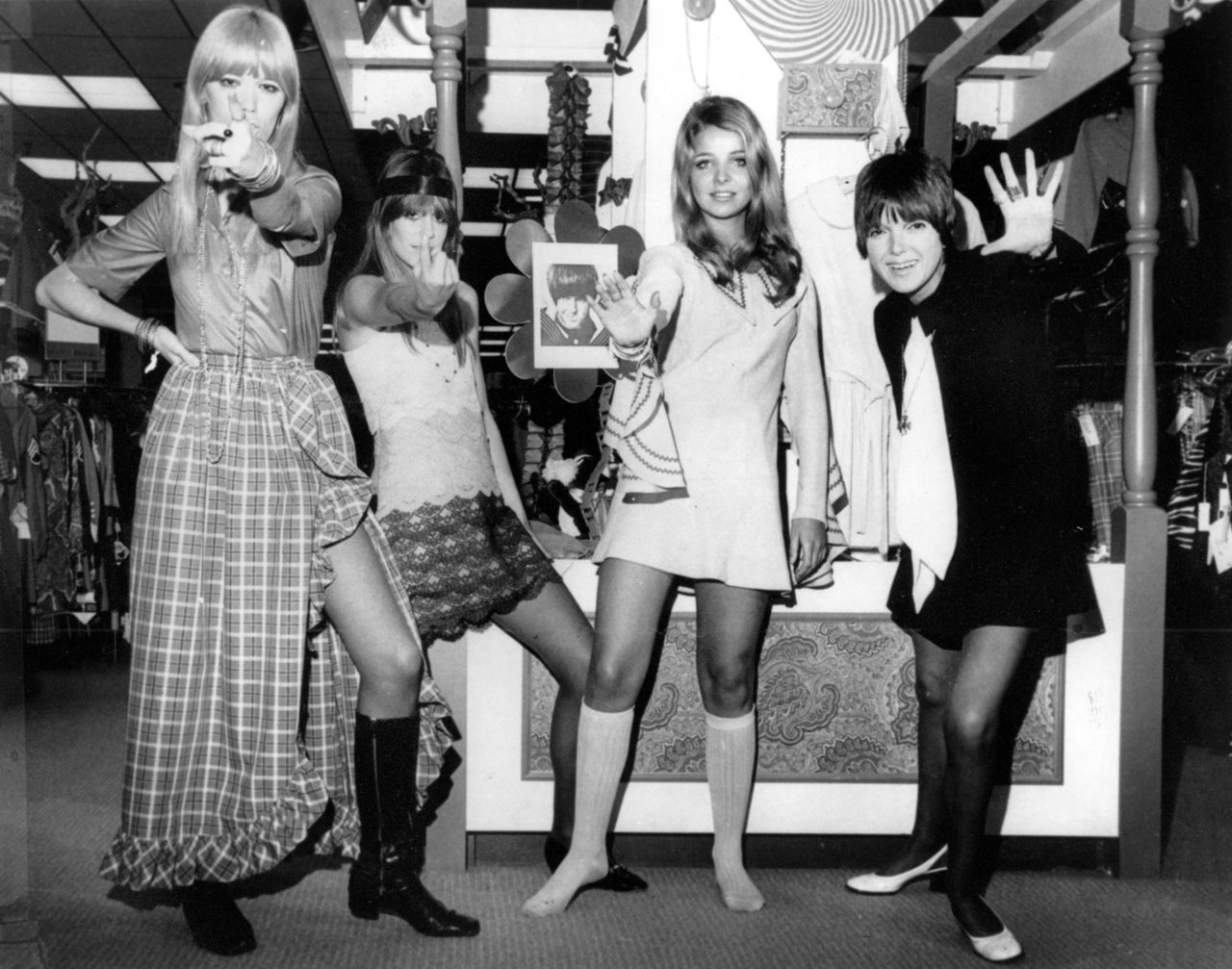

The clothing worn by flappers and mods reflected a break from previous feminine ideals and gender roles, shocking the older generations. Flappers challenged traditional notions of femininity by including variations of menswear in their wardrobes, including vests, Fair Isle sweaters, and striped sailor shirts (Fig. 24)(Breunig). However, she is most remembered for the “flapper dress.” It was the length, not necessarily the shape of the flapper’s dress that came under fire in the 1920s. Indeed, the “straight silhouette” was increasingly popular since about 1910, and the “straight-line, one-piece frock” dominated the mode of the 1920s (“Fashion: 30 Years of the Mode” 66-67). However, the flapper’s “ridiculous” knee-length dress and rolled stockings revealed more leg than ever before (Wigmore et al.). Critics of the flapper’s short dress would have been scandalized by minis of the 1960s. Keeping with the spirit of the times, fashionable women of all ages were shortening their skirts. However, minis “strictly for those under twenty” could be more than five inches above the knee (Fig. 23) (Barmash; Livingstone). The older generation harshly objected to the mini, prompting protests by schools and churches (Barmash). In addition, mod clothing also incorporated elements from menswear (or boyswear), like the Mary Quant ensemble modeled by Twiggy in Figure 25.

Slim bodies, cropped hair, and menswear-inspired clothing combined to create an androgynous, boyish look shared by both flappers and mods. In 1927, Red Book Magazine published a poem called “To A Flapper,” written by Berton Braley (Braley 30). Braley revealed that he was actually glad that the flapper rejected corsets, and liked her short skirts and rolled stockings. However, he went on to heavily scrutinize her “boyish flat form,” “boyish bob,” and “garb that is mannish.” He concluded that, in their unsuccessful efforts to “be male,” flappers were negating all of their feminine charm. Similar criticisms befell the boyish appearance of short-haired mod girls, the waifish Twiggy being the most high-profile target. One New York Times reporter described her as “your next door neighbor, if he happens to be a 12-year-old boy” (Curtis). Judith Crist, a critic for Ladies’ Home Journal, blamed Twiggy for bringing “the age of the hermaphrodite” (Crist 60). Crist awaited the end of Twiggy’s fame, hoping that the next “crop” of teens would be “female in a slightly lusher sense and bear a resemblance to the girl, rather than the boy, next door” (Crist 60).

Fig. 21 - Artist unknown. Fashion: As You Are, 1922, January 1923. Source: Vogue

Fig. 22 - Bettmann. Leonard of London cuts model Twiggy's hair, April 1967. U1551947. Source: Getty Images

Fig. 23 - Tony Othen and Bede Associatio. Mod girls at the Lady Gomm Club in Hawstone Road, 1969. London, UK: Museum of Youth Culture. Source: Google Arts & Culture

Fig. 24 - Photographer unknown. Group of flappers and man seated at a piano, October 1923. Photographic print. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, No. 26779. Source: Library of Congress

Fig. 25 - Terence Donovan (British, 1936-1996). Twiggy modeling a waistcoat ensemble by Mary Quant., October 1966. UK: Ernestine Carter Archive, Fashion Museum/Bath and North East Somerset Council. Source: Bloomsbury Fashion Central

Fig. 26 - Unknown. Charleston dance contest at the Parody Club, New York City, 1926. Source: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Fig. 27 - John Cowan (British, 1929-1979). Mary Quant and Alexander Plunket Greene dancing., ca. 1962. Paper. London: The Cowan Archive, Museum of London, IN34718. Source: Museum of London

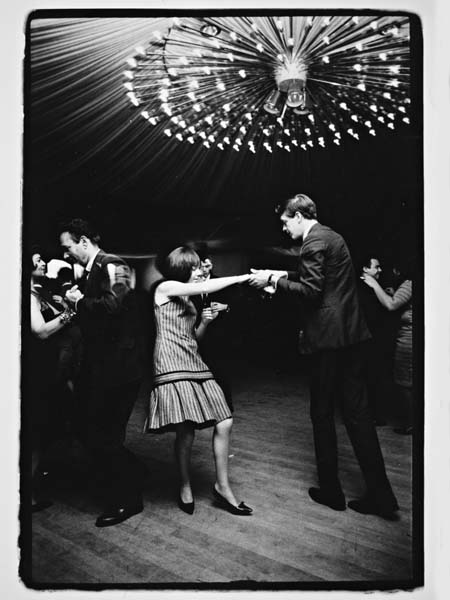

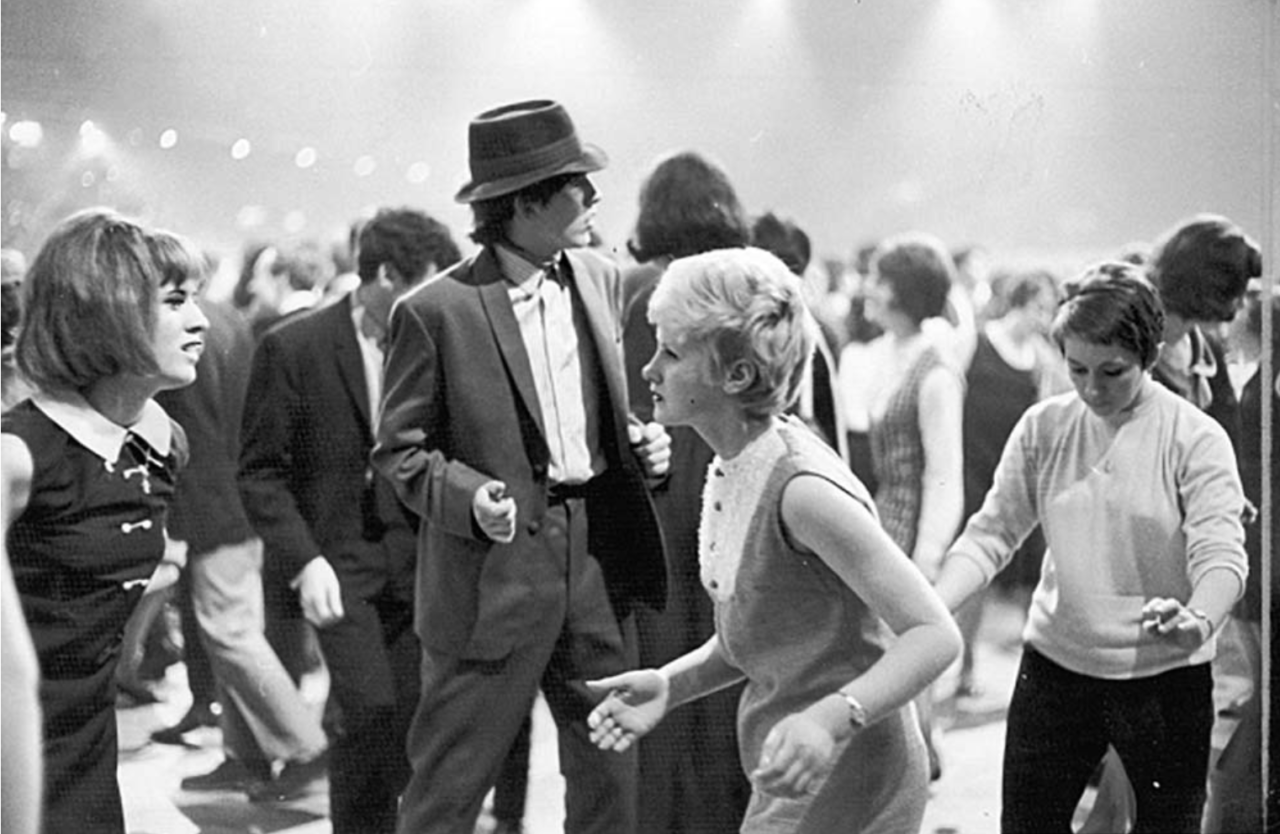

The costume and behavior of flappers and mods were both heavily influenced by controversial new music genres and dances. Flappers were lovers of jazz music, and dances like the Charleston and the Black Bottom (Fig. 26) (Hannel). The desire to comfortably engage in such energetic dances was one of the greatest influences on the flapper’s costume. Short, sleeveless frocks liberated the arms and legs, and cropped hair was undisturbed by rigorous movement. However, jazz would only became mainstream in the coming decades. In the early 1920s, it was thought to be evil, savage, violent, and corrupting (Faulkner). Music was also crucial to the mods, who were fans of modern jazz, rhythm and blues, blues, and bluebeat (Lewis). They would spend their weekends at dance clubs, possibly dancing the frug, jerk, and watusi (Figs. 27-29) (Jenss). As such, mods valued garments that channeled jazz and allowed for freedom of movement (“Mary Quant Pop Art Meets Pure Jazz”). In 1964, the television program Ready, Steady, Go! hosted a “great Mod Ball,” broadcasting eight thousand young London mods dancing the latest trends (Laurie). However, parents of teenagers questioned the morality and physical safety of their music and dancing. In 1965, one dismayed eighteen-year-old wrote in to Seventeen to defend teen dance crazes, concluding: “After all, wild dances weren’t invented in the sixties (what about the Charleston?)” (Block 204).

Fig. 28 - Daily Mirror/Mirrorpix/Getty Images. Mods dance and play at the Empire Pool, Wembley, London, April 1964. 592230650. Source: Getty Images Gallery

Fig. 29 - Daily Mirror/Mirrorpix/Mirrorpix via Getty Images. The Glad Rag Ball at the Empire Pool, Wembley, London, November 1964. 592261190. Source: Getty Images Gallery

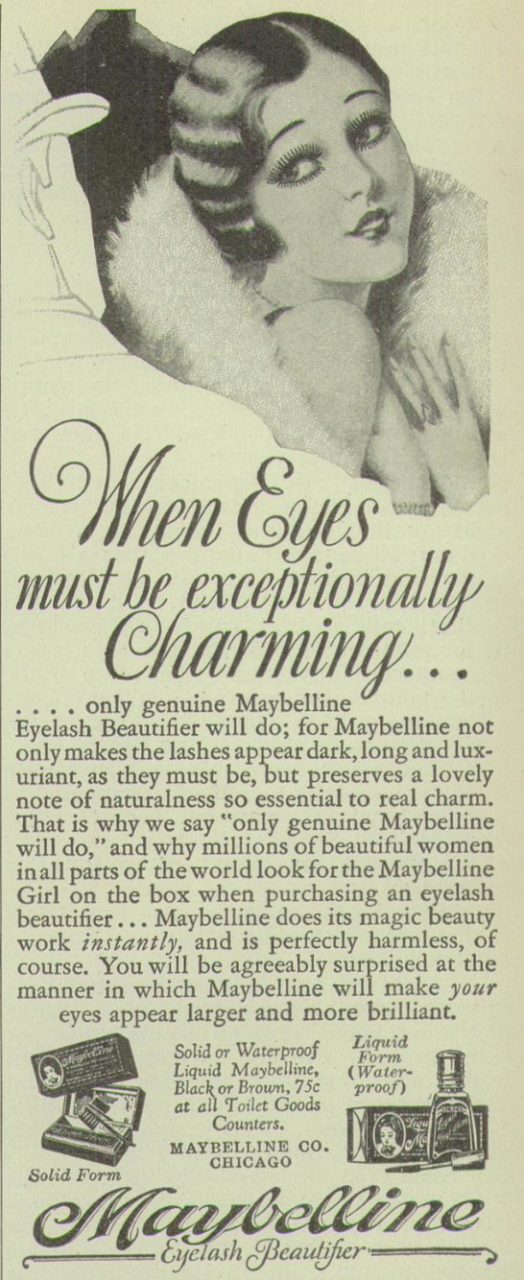

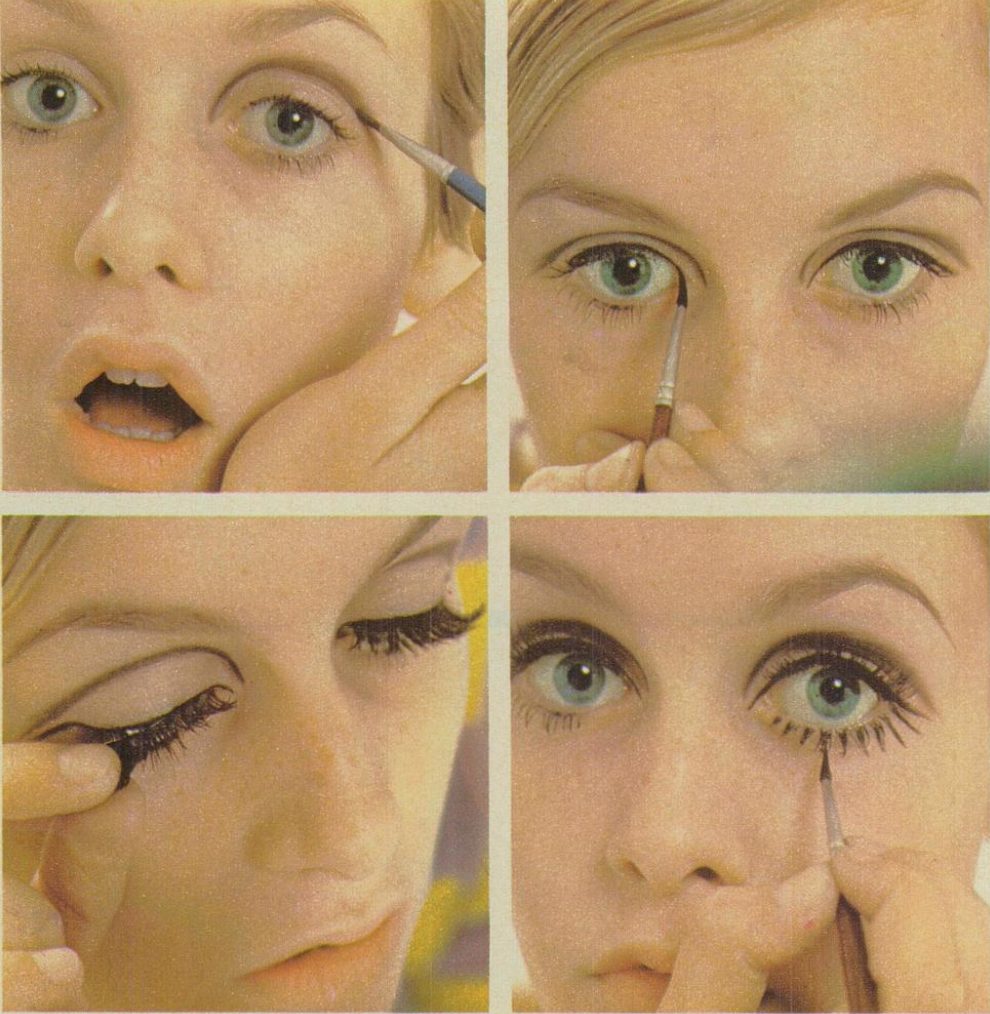

Cosmetics and beauty practices were crucial to flappers and mods, and many of their goals were shared. In an effort to emphasize their eyes, flappers plucked their eyebrows and used kohl liner and mascara (Fig. 30) (Hockenhull). They also used rouge and red lipstick. Many were shocked by the unprecedentedly brazen use of makeup in what was deemed “The Cosmetics Age” (Currie 30). Contemporaries of the flapper criticized her makeup on aesthetic grounds for being “crude as a clown’s” (Wigmore et al.). However, it was also criticized for being ungodly and threatening to health (Lowry; Flapper’s Cosmetics Alarming Physicians: Dr. Love Fears For What Modern Girl Will Look Like At 40”). By the 1960s, the use of makeup no longer scandalized. Like the flappers, mods desired to emphasize their eyes, and did so with shadows, liners, and mascara (Fig. 31) (Jenss). A 1967 issue of Seventeen revealed Twiggy’s signature makeup tutorial, which included eye-enlarging shadow techniques, mascara, several pairs of false eyelashes, and drawn-on lower lashes (Fig. 32) (“Twiggy”). However, mod makeup styles were also criticized in the press. One 1964 Vogue Beauty Bulletin asserted that no professional makeup expert liked the “outward-drawn eyeline” of “modly” eyeliner (“Beauty Bulletin: One New Theory On The Way Make-Up Is Moving Now”).

Fig. 30 - Artist unknown. Maybelline Advertisement, October 1929. Source: Hearst's International Combined with Cosmopolitan

Fig. 31 - Mary Quant Cosmetics. Box of 10 'eye crayons', 1966-1974. London: Museum of London, 74.330/32kkb. Source: Museum of London

Fig. 32 - Rik van Glintenkamp. Twiggy's makeup tutorial, March 1967. Source: Seventeen

Conclusion

T he world of the 1960s was a drastically different from that of the 1920s, yet they both spawned strangely similar responses in young women’s alternative fashion (Fig. 33). As youth subcultures, flappers and mod girls rebelled against the traditional image of femininity held by the generation before them. In both instances, the rebellious spirit of the times was prompted by great victories (such as the end of WWI, women’s suffrage, and the sexual revolution), challenging authority (including protesting prohibition, the Vietnam war, and civil rights movements), and cultural phenomena (such as jazz and pop music). As a result, flappers and mods rejected the aesthetic values of their parents and engaged in new, “modern” lifestyles. They desired to look youthful rather than mature, idealizing a slim, straight figure. They showed a shocking and unprecedented amount of leg, while also incorporating elements of menswear into their wardrobes. All flappers and many mods cut their hair in a short, “boyish” style. Furthermore, they were criticized by the public for their use of cosmetics and other beauty practices – mainly used to emphasize the eyes. Despite the regular scrutiny that flappers and mods faced in the press, both for their appearances and behaviors, one could say they won the day. Media professionals and fashion designers profited off of proliferating those subcultures into the mainstream. They were very successful in doing so, as the fashion impulses of flappers and mods truly met the demand of their revolutionary times.

Fig. 33 - Terry Fincher/Express/Getty Images. Twiggy wearing 1920s style fashions, November 1966. Hulton Archive, 99n/19/huty/13482/01. Source: Getty Images

References:

- Barmash, Isadore. “Miniskirts Are Raising Some Retailing Eyebrows.” New York Times (1923-Current File), December 4, 1966. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/117595037?accountid=27253.

- “Beatlemania U.S.A.” Seventeen, April, 1964, 175, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/2047138066?accountid=27253.

- “Beauty Bulletin: Make-up report to Americans.” Vogue, February 1, 1965, 172-177, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/879254040?accountid=27253.

- “Beauty Bulletin: One New Theory On The Way Make-Up Is Moving Now.” Vogue, April 15, 1964, 120-122, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/904295775?accountid=27253.

- “Beauty Checkout: Automatic Lift/The Twiggy Figgah…” Vogue, June 1, 1967, 60, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/879267424?accountid=27253.

- Block, Nancy. “Critics of Teen Dances See Moral Danger Where None Exists.” Seventeen, October, 1965, 204, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/2007376848?accountid=27253.

- Braley, Berton. “To a Flapper.” Red Book Magazine, April, 1927, 30, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1807551968?accountid=27253.

- Breunig, Lisa Pierce. “Flappers and Chanel.” In Pop Culture Universe: Icons, Idols, Ideas, ABC-CLIO, 2020, popculture2.abc-clio.com/Topics/Display/3?cid=182.

- Bullitt, Helen Lowry. “Still the Cosmetic Urge.” New York Times (1857-1922), June 18, 1922. 46. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/99503174?accountid=27253.

- Crist, Judith. “What Twiggy’s Got.” Ladies’ Home Journal, June, 1967, 60, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1916727314?accountid=27253.

- Currie, Barton W. “The Cosmetic Age.” Ladies’ Home Journal, February, 1926, 30, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1876386143?accountid=27253.

- Curtis, Charlotte. “Twiggy: She’s Harlow, and the Boy Next Door.” New York Times (1923-Current File), March 21, 1967. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/118090982?accountid=27253.

- de la Haye, Amy. “Quant, Mary.” In Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele, 71-74. Vol. 3. Detroit, MI: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2005. Gale eBooks (accessed May 7, 2020). https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3427500472/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=af51058d.

- “Defends Flapper as a Normal Girl: Secretary of Labor Davis In Mother’s Day Address at Arlington Sees Her Future Sure.” New York Times (1923-Current File), May 10, 1926. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/103878395?accountid=27253.

- Devlin, Polly. “Fashion: Paris: Twiggy Haute Couture.” Vogue, March 15, 1967, 65, 147. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/879264737?accountid=27253.

- Divita, Lorynn R. “Subcultures.” In Fashion Forecasting, 131–150. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501338663.ch-007.

- “Fashion: 30 Years of the Mode.” Vogue, 1923, 63-68, 178, 180, 182, 184, 186, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/897852735?accountid=27253.

- “Fashion: As You Are, 1922.” Vogue, 1923, 45, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/897858998?accountid=27253.

- “Fashion: The Term ‘Flapper’ Carries No Stigma.” Vogue, June 1, 1917, 79, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/879154809?accountid=27253.

- Faulkner, Anne Shaw. “Does Jazz Put The Sin In Syncopation.” Ladies’ Home Journal, August, 1921, 16, 34, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1876403679?accountid=27253.

- “Features: Short Cuts to Chic.” Vogue, July 15, 1926, 65-67, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/879167549?accountid=27253.

- “Features: The Crowning Glory of Youth.” Vogue, August 15, 1925, 100, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/879166345?accountid=27253.

- “Fitzgerald, F. Scott.” In Gale Contextual Encyclopedia of American Literature, 526-529. Vol. 2. Detroit, MI: Gale, 2009. Gale eBooks (accessed April 27, 2020). https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3008100169/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=dcae70fb.

- “Flapper’s Cosmetics Alarming Physicians: Dr. Love Fears For What Modern Girl Will Look Like At 40.” New York Times (1857-1922), April 13, 1922. 10. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/98783104?accountid=27253.

- Gianoulis, Tina. “Gibson Girl.” In 1900s-1910s, edited by Sara Pendergast and Tom Pendergast, 84-85. Vol. 1 of Bowling, Beatniks, and Bell-Bottoms: Pop Culture of 20th-Century America. Detroit, MI: UXL, 2002. Gale eBooks (accessed April 30, 2020). http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1023726400.

- Gibson, Pamela Church. “Twiggy.” In Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele, 354-355. Vol. 3. Detroit, MI: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2005. Gale eBooks (accessed April 25, 2020). https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3427500601/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=72660c2d.

- “Hairdos Of The Month.” Seventeen, September, 1965, 224-225, 228, 230, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/2007374214?accountid=27253.

- Hannel, Susan L. “The Influence of American Jazz on Fashion.” In Twentieth-Century American Fashion, edited by Linda Welters and Patricia A. Cunningham, 57–78. Dress, Body, Culture. Oxford: Berg, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/9781847882837/TCAF0008.

- Heilbroner, Robert L. “Marilyn Monroe.” Cosmopolitan, May, 1953, 39. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1999145732?accountid=27253.

- Hillis, Marjorie. “Fashion: Fitting the Flat Back to the Full Figure.” Vogue, November 15, 1923, 44-44, 45, 128, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/879168196?accountid=27253.

- Hockenhull, Stella. “Modish and Modern: Interwar Fashion and the Changing Role of Women.” In Pop Culture Universe: Icons, Idols, Ideas, ABC-CLIO, 2020. http://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2451/Topics/Display/1793941?sid=1793938&cid=91.

- Jenss, Heike. “Icons of Modernity: Sixties Fashion and Youth Culture.” In Fashioning Memory: Vintage Style and Youth Culture, 37–64. Dress and Fashion Research. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474262002.ch-003.

- “John Held Jr., Cartoonist, Dies; Satirist of the Twenties Was 69.” New York Times (1923-Current File), March 3, 1958. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/114607267?accountid=27253.

- Laurie, Peter. “Features/Articles/People: So Young, so Cool, so Misunderstood–Mods and Rockers.” Vogue, August 1, 1964, 68-69, 129, 135, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/897852122?accountid=27253.

- Livingstone, Janet. “The Hemline Dilemma: Which Length For You?” Good Housekeeping, July, 1968, 74-77, 192, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1884670285?accountid=27253.

- “Mary Quant Pop Art Meets Pure Jazz.” Seventeen, September, 1965, 106-107, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/2007374633?accountid=27253.

- Moffitt, Jennifer. “New Fashion, New Women: The Flapper As Product and Producer of Changing Gender Roles in the 1920s.” In Pop Culture Universe: Icons, Idols, Ideas, ABC-CLIO, 2020. http://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2451/Topics/Display/1793941?sid=1793940&cid=91.

- Quant, Mary. “Features/Articles/People: The Young Will Not Be Dictated To.” Vogue, August 1, 1966, 86-89, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/897852584?accountid=27253.

- Sauro, Clare. “Flappers.” In Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele, 88-89. Vol. 2. Detroit, MI: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2005. Gale eBooks. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3427500245/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=9aa4a3b5

- Steele, Valerie. Fifty Years of Fashion: New Look To Now. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/955193317

- “The Fitter is a Girl’s Best Friend.” Seventeen, October, 1955, 82-85, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/2007366334?accountid=27253.

- “The ‘60s: When Women Made the Fashion.” Women’s Wear Daily, December 30, 1965, 4-5, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1565116887?accountid=27253.

- Tortora, Phyllis G., and Sara B. Marcketti. “The Sixties and Seventies: Style Tribes Emerge 1960–1980.” In Survey of Historic Costume, 540–589. New York: Fairchild Books, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501304194.ch-018.

- “Twiggy Borrows from the Boys.” Seventeen, July, 1967, 60-61, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/2013794512?accountid=27253.

- “Twiggy by Twiggy.” Cosmopolitan, October, 1967, 104-109, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/2007369250?accountid=27253.

- “Twiggy.” Seventeen, March, 1967, 116-119, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/2013813390?accountid=27253.

- “Want Flapper Called ‘Modern’; Camp-Fire Girls War on Term.” New York Times (1923-Current File), October 6, 1925. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/103438415?accountid=27253.

- Wigmore, Katherine, Peggy Stoddard, Patsy Brooks, and Anonymous. “Has the Flapper Disappeared?” The Junior League Magazine, January, 1928, 16-17. https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:RAD.SCHL:10642406?n=18.

- Wollstein, R. Heylbut. “Girls — Seen By Edna Ferber.” New York Times (1923-Current File), May 11, 1924. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/103347878?accountid=27253.