A xicolli is a sleeveless, sewn vest usually embellished with fringe that comes in various lengths worn by priests and high rank warriors in ancient Mesoamerican cultures.

The Details

Chloe Sayer describes the typical pre-conquest clothing worn in what is now Mexico, as well as the men’s xicolli, in the Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion (2010):

“By 400 B.C.E., some men had adopted a short cloak and a hip-length xicolli (sleeveless jacket open in the front). The xicolli, associated with male deities, was often worn by priests. During important ceremonies, priests were required to impersonate deities. A plain-woven cotton xicolli, fringed and painted with sacred designs, was found in 2005 by archaeologists in Mexico City. Preserved in a stone box at the heart of the Aztec precinct of the Templo Mayor, this important garment was probably worn by a priest to impersonate Tlaloc, the chief rain deity.” (231)

Figure 1 is a depiction of the open-front xicolli worn on a Mayan warrior, dating to ca. 550-950 AD. This xicolli is unfringed/unadorned at the hem, possibly due to the fact that it would get in the way during battle or perhaps it is a simplification by the artist.

Within The Essential Codex Mendoza (1997), the editors, Frances Berdan and Patricia Rieff Anawalt translated an entire set of articles from ancient Mesoamerica describing the typical dress along with diagrams, specifically mentioning the xicolli on multiple occasions:

“The head priest wears the xicolli, a fringed, sleeveless jacket that tied in the front (its sleeved appearance is due to the wide garments draping off the shoulders and thus forming a fold under the arm). Among the Aztecs, this was a special-purpose costume restricted to males, who wore it solely in a ritual or official context: it appears only on gods, diety impersonators, priests, and special envoys of the emperor.” (179)

Similarly, figure 2 is a standing sculpture of a high-class Mayan individual, dating between 550 and 950 AD. This statue is donning the open front xicolli paired with heavy adornment on the body. Sotheby’s describes the statuette as:

“the awobab distinguished by the elaborate facial tattoos and regal expression and gesture, wearing a lattice patterned xicolli, wide belt with shell danglers, large collar tied at the back and with shell pendant, fillet headband, bracelets and earrings.”

Regardless of specific culture, the xicolli remains a sacred garment reserved for the high ranks.

Figure 3 can be seen as an example of a Mayan vessel utilized for rituals of the priests. This is a ceramic cylinder from the 7th-9th century that would have been utilized to hold a bowl of incense during rituals; this depicts the sun deity, adorned with a feathered and fringed xicolli proving his utmost importance to the culture.

Authors Susan Toby Evans and David L. Webster describe dress within pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures, such as the traditional xicolli jacket in the encyclopedia, Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America (2001):

“The xicolli, a short, sleeveless jacket, has a diagnostic hem area that usually displays some form of elaboration, often a fringe. This garment was an important ritual costume in highland central Mexico from Middle Formative Tlatilco times through the Classic period at Teotihuacán and up to the Spanish colonial era. The xicolli appears on wall murals and ceramic vessels at Teotihuacán, worn by lavishly dressed males. The important personages – perhaps priests or deity impersonators – are shown in profile.” (153)

Last, in Daily Life of the Aztecs on the Eve of the Spanish Conquest (1970), author Jacques Soustelle describes the variations of the xicolli in the Aztec culture:

“Sometimes the priests and the warriors wore, under their cloaks or instead of them, a very short-sleeved tunic, the xicolli, which opened in front and which could be closed by tying a ribbon. Another version of the xicolli had no opening, but had to be pulled over one’s head like a shirt or like the blouse (huipilli) that the women wore.” (134)

As seen in figure 4, the Metropolitan Museum of Art has a Mayan plate from the 8th century AD depicting a man playing a trumpet; this is a man of high stature due to his xicolli and trumpet. This xicolli is woven with feathers attached and open at the front. This variation is open at the front, like mentioned by Soustelle.

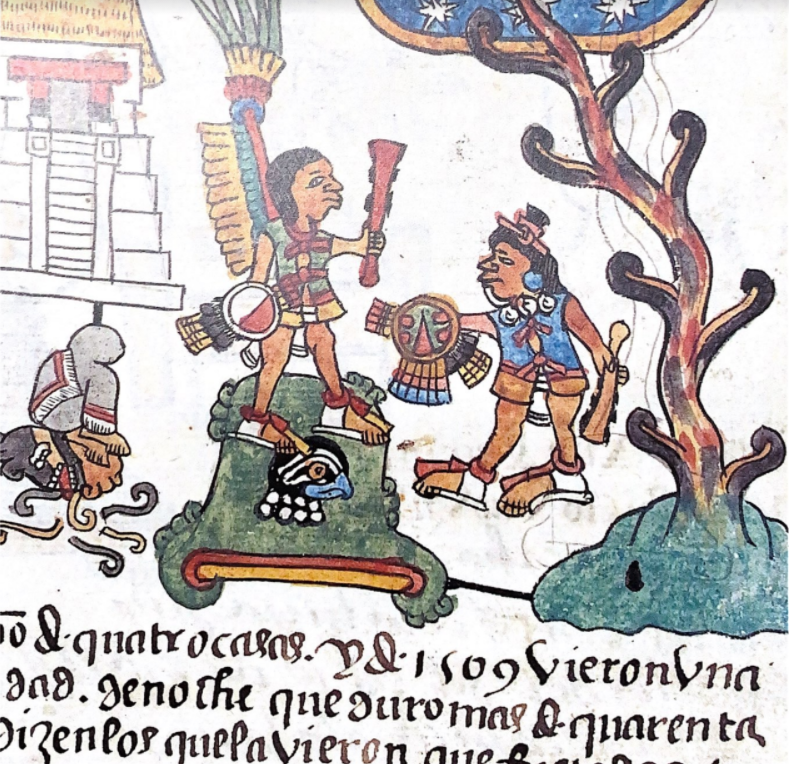

Figure 5 comes from the Telleriano-Remensis Codex, a shining example of Aztec manuscript painting created in the 16th century. This image is another visual depiction of what Soustelle wrote; these Aztec warriors are seen with the more common ribbon closure on their xicolli, adorned with fringed hems.

Xicolli were worn for centuries as markers of status and ranking in many Mesoamerican cultures. Depicted in many artistic forms, xicolli are an example of clothing worn in the Americas before the Spanish invasion.

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown (Mayan). A Fine Mayan Standing Figure, 550-950 AD. New York: Sotheby's. Source: Sotheby's

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown (Mayan). Mayan Standing Dignitary, 550-950 AD. Clay. New York: Sotheby's. Isidore Cohen. Source: Sotheby's

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown (Mayan). Censer Support, 7th-9th century AD. Ceramic; h 54 x w 28.9 x d 34.9 cm (h 21 1/4 x w 11 3/8 x d 13 3/4 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1978.412.99. The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Raymond Wielgus, 1963. Source: The Met

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown (Mayan). Plate with Trumpeter, 8th century AD. Ceramic; h 6.4 x w 32.4 x d 32.4 cm (h 2 1/2 x w 12 3/4 x d 12 3/4 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989.110. Gift of Eugene and Ina Schnell, 1989. Source: The Met

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown (Aztec). Codex Telleriano-Remensis, 16th century. France: Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Source: BNF

References:

- Berdan, Frances, and Patricia Rieff Anawalt. The Essential Codex Mendoza. Google Books. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Essential_Codex_Mendoza/JQeAQZHev0IC?hl=en&gbpv=0

- Evans, Susan Toby, and David L. Webster. Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America: An Encyclopedia. United Kingdom: Garland Pub., 2001. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Archaeology_of_Ancient_Mexico_and_Centra/vY8Cb3Vc7LMC?hl=en&gbpv=0

- Quiñones Keber, Eloise. Codex Telleriano-Remensis : Ritual, Divination, and History in a Pictorial Aztec Manuscript. 1st ed. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1995. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/902061424

- Sayer, Chloë. “Overview of Mexico.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: Latin America and the Caribbean, edited by Margot Blum Schevill, 23–33. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2005. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/7377819815

- Soustelle, Jacques. Daily Life of the Aztecs on the Eve of the Spanish Conquest. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1970. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/51076157