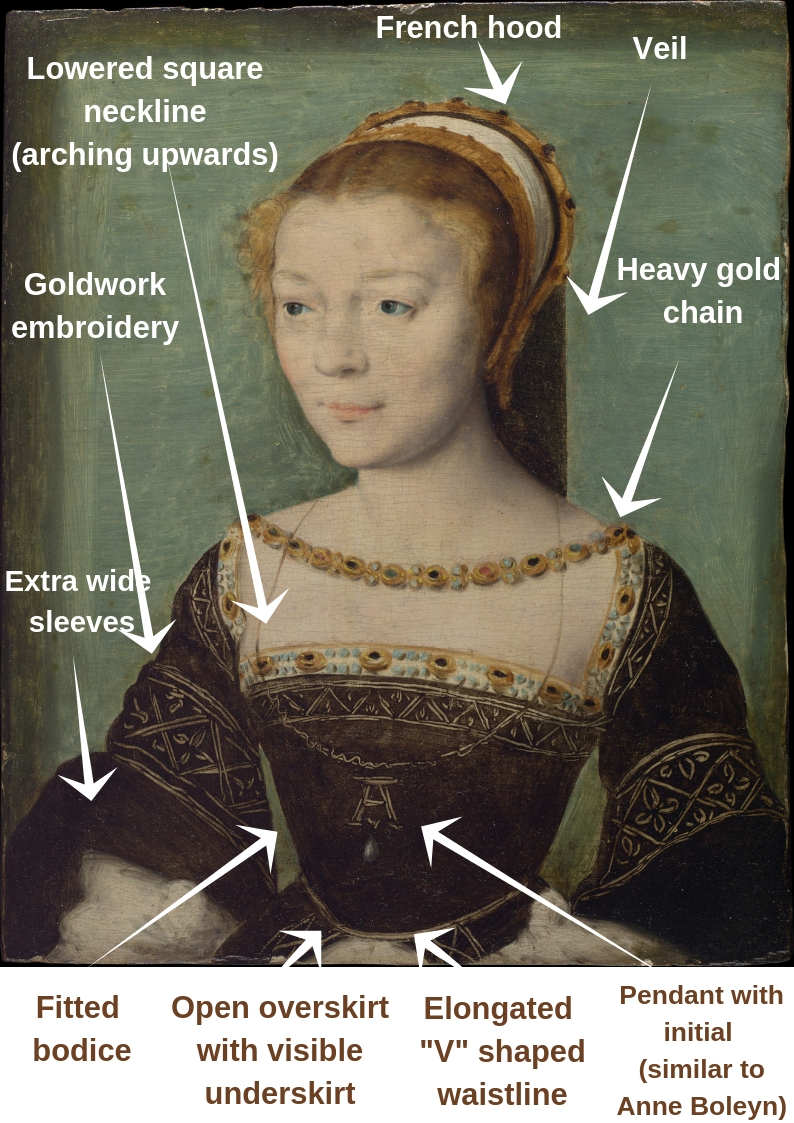

Anne de Pisseleu, Duchesse d’Étampes, exemplifies fashionable women’s dress in France c. 1535-1540 with her tight bodice with lowered square neckline, inverted “V” shaped skirt with visible underskirt, and French hood headdress.

About the Portrait

C

orneille de Lyon, also known as Corneille de La Haye, was a Dutch painter active in Lyon, France since 1533 (Fig. 1). Both names were given to the artist based on the cities he was associated with–he worked in Lyon and supposedly was from Hague. We don’t know his real last name.

Corneille de Lyon is known to be the painter to Queen Eleanor, the second wife of Francis I of France, and to the Dauphin, later Henry II, from the 1540s onwards. Although there are a number of contemporary references mentioning Corneille de Lyon as a well-known portrait painter at the time, there is only one work that can be attributed to him with certainty. It is a portrait of Pierre Aymeric that was signed by the sitter (Fig. 2). Pierre Aymeric’s portrait helped to confirm the attribution to Corneille de Lyon of a number of other works based on “their small size, their sensitive naturalistic modeling in a northern manner, and usually by a green background” (Blunt 75) (Figs. 3-4). There is no evidence of the artist’s early training but the modeling in “thin glazes which give the variety of light and texture to the features” suggests that he learned his technique in France rather than in his home country (Blunt 73). Most of his portraits were intended for intimate viewing, probably by the sitter or a loved one.

While some historians believed that this painting is more likely to be the work of a French painter Jean Clouet (Palustre), the Met currently attributes the portrait to Cornelle de Lyon and names the sitter as Anne de Pisseleu, Duchesse d’Étampes. As French historian Anne Dubois de Groër suggests, the French court made numerous trips to Lyon between 1536-37, and the painting could have been made during one of these visits (Dubois de Groër 131–133). The analysis below confirms that the sitter’s dress is consistent with the French court fashion between 1535 and 1540.

The Met informs us that the sitter was identified by inscriptions on several early copies and by the pendant with a letter “A” (Anne’s initial). A replica of this portrait sold at Sotheby’s in 2017 and currently located in a private collection shows a more elaborate pendant, chain, and dress embroidery (Fig. 5).

There is another miniature portrait in the Met collection attributed to Corneille de Lyon that strikingly resembles Anne de Pisseleu (Fig. 6). This portrait is not identified. However, the facial features of the sitter allow us to suggest that it might be another portrait of Anne de Pisseleu, Duchesse d’Étampes.

Anne de Pisseleu was the chief mistress of Francis I of France. Anne came from the noble family of Pisseleu and was introduced to the French court by 1522 as a maid of honor to Louise of Savoy, mother of Francis I. She met Francis I when he returned to France in 1526 after several years of captivity in Spain. The king fell in love with Anne who had a great influence on the monarch for over 20 years. At the time of the sitting, Anne was about 30 years old. She was known for her beauty and intelligence. Francis I revived an old dukedom of Étampes and appointed Anne the Duchesse d’Étampes in 1536 to give her official status at the court (Desgardins 19). Here is how Frank Hamel describes Anne de Pisseleu’s influence on Francis I in Fair Women at Fontainebleau (1909):

“From the day of his birth to the day of his death, Francois I was ruled by petticoat government. First there was his mother, the imperious Louise de Savoie, then his too loving sister, Marguerite, Queen of Navarre, who devoted herself entirely to his affairs, and neglected her own; later his mistresses reigned, and no one possessed more power than one of them, the beautiful Anne de Pisseleu, Duchesse d’Étampes, whose every wish became his law.” (50)

After the king’s death in 1547, however, Anne was dismissed from the court. Unfortunately, at the end of her life, she seems to be totally forgotten since we don’t even have any notes about the exact year of her death; the Met suggests that she died in 1576.

Fig. 1 - Attributed to Corneille de Lyon (Dutch, 15??-1575). Self-portrait of Corneille de Lyon (De La Haye), ca. 1565-1570. Chalk, charcoal, wiped, brush, washed; 13.4 x 18.9 cm. Vienna: Albertina Museum, Inv. 82802. Source: Albertina Museum

Fig. 2 - Corneille de Lyon (Dutch, 15??-1575). Pierre Aymeric, 1534. Oil on wood; 16.5 x 14.2 cm (6.4 x 5.5 in). Paris: Louvre Museum, RF 1976-15. Source: Louvre Museum

Fig. 3 - Corneille de Lyon (Dutch, 15??-1575). Catherine de' Medici (1519-1589), ca. 1536. Oil on panel; 16.5 x 15.2 cm (6.4 x 5.9 in). Mole Valley, United Kingdom: Polesden Lacey. National Trust Collection, 1246458. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 4 - Corneille de Lyon (Dutch, 15??-1575). Portrait of Louise de Rieux, ca. 1550. Oil on panel; 16 x 12 cm (6.2 x 4.7 in). Paris: Louvre Museum, RF 669. Source: Louvre Museum

Fig. 5 - Corneille de Lyon (Dutch, 15??-1575). Portrait of Madame Anne de Pisseleu, Duchess d’Étampes, 16th century. Oil on panel; 17 x 14 cm (6.75 x 5.5 in). Private Collection. Source: Sothebys

Fig. 6 - Attributed to Corneille de Lyon (Dutch, 15??-1575). Portrait of a Young Woman, 16th century. Oil on panel; oval, 14.6 x 13 cm (5 3/4 x 5 1/8 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 41.190.533. Bequest of George Blumenthal, 1941. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Attributed to Corneille de Lyon (Dutch, 15??–1575). Anne de Pisseleu (1508–1576), Duchesse d’Étampes, ca. 1535–40. Oil on wood; 7 x 5 5/8 in. (17.8 x 14.3 cm). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 29.100.197. H. O. Havemeyer Collection. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

About the Fashion

The painting is a 3/4 view half-portrait of Anne de Pisseleu on a green background. The sitter is wearing a dark brown dress with a tightly fitted bodice and funnel-shaped loose sleeves. Based on the painting technique, one can assume this was a velvet dress. There are a few records that confirm the popularity of velvet at the time. For example, Blum mentions an earlier work with a list of fabrics and articles of clothes ordered by Francis I for the gentlemen and ladies of his court between 1532 and 1538 including “black velvet, black and white taffeta, linen of gold or silver linen, crimson satin, Dutch chemises, muffs, and cannetilles” (Blum 8). Croizat cites a payment record from Francis I’s account books in 1538 for a purple and crimson velvet to make dresses for the ladies of his household, including Anne de Pisseleu d’Heilly (Croizat 119).

Anne’s low-cut squared neckline is slightly arched upwards and is adorned with pearls and jewels. The fabric itself is solid with intricate gold embroidery. This might serve as an additional confirmation that the subject portrait was created before the mid-century when rich brocades became more popular.

Fashion historian Phyllis Tortora in her book Survey of Historic Costume (2015) provides a detailed overall description of women’s costume in the 16th century as well as the specific changes to the costume over decades. In particular, she notes that due to the Spanish influence, there was a tendency to emphasize dark colors, especially black starting from the 1530s (Tortora 185). In addition to the portrait, we can find numerous paintings from that time period confirming her words (Figs. 3, 4, 8).

The sitter’s silhouette resembles an hourglass with a narrow bodice, defined waistline, and full skirt with an inverted V-shaped opening at the front. Her bodice looks flat, rigid, and has an elongated “V” shape at the front. A very similar dress is shown in 19th-century engraving depicting Claude of France, the first wife of Francis I (Fig. 7). Claude is shown wearing a velvet dress with large fur sleeves. Her skirt is open at the front to reveal a beautiful brocade underskirt.

The accessories

The main accessories at the time consisted of chain necklaces, large pendants, and rings. Exquisite gold chains worn by the sitter and the rich gold embroidery of her dress suggest her high social rank. Anne also wears a jeweled belt that can be better seen on the above-mentioned copy (Fig. 5). Tortora provides a detailed explanation to the construction of the jeweled belts worn at the time:

“A rich, jeweled belt outlined the waistline, and from the dip, in front, its long end fell down the center front of the gown almost to the floor.” (185)

A similar belt can be seen on the engraving showing Claude of France (Fig. 7).

The French hood worn by the sitter was a popular women’s headdress at the time. It opened to reveal the front part of the hair and was less conservative than the angled gabled hood. It was often worn over a coif, decorated with pearls, and had a black veil attached to the back that fell below shoulders (Ruppert 20). We can see almost identical headdresses worn by other ladies painted by Corneille de Lyon (Figs. 3-4, 9-10).

Even though we cannot see the sitter’s undergarments, Anne most probably wears a chemise decorated with blackwork to protect her expensive dress from body oils and soil. Tortora also mentions the undergarments called stays or a pair of bodys. They were meant to shape the body as well as to protect the outer garment from being soiled. Stays were made of two layers of fabric stiffened with glue, shaped as an under-bodice, cut into two sections and fastened with laces or tapes at the front and back (Tortora 183).

The setting & context

The costume worn by the king’s chief mistress–which was a semi-official position at French court–looks rich and formal. The sitter’s elaborate headdress, lavish jewelry, and delicate goldwork embroidery of the dress suggest her high social status and wealth. Cornelle de Lyon is known for the small size of his portraits that were usually meant for private enjoyment. As a result, the artist drew more attention to the facial features of his model rather than to her accessories or background.

Fig. 7 - Hippolyte Pauquet after Gaignieres from the Pauquet Brothers' "Modes et Costumes Historiques" (Historical Fashions and Costumes), Paris, 1865 (French). Claude of France. Handcolored steel engraving. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 8 - Netherlandish painter. Portrait of a lady, bust-length, in a blue dress, holding a puppy, ca. 1540–50. Oil on wood; 74.3 x 57.5 cm (29 1/4 x 22 5/8 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 69.282. Gift of Winston F. C. Guest, 1969. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 9 - Corneille de Lyon (Dutch, 15??-1575). Portrait of a lady, bust-length, in a blue dress, holding a puppy, 16th century. Oil on panel; 17.8 x 15.6 cm (7 x 6.1 in). Private Collection. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 10 - Corneille de Lyon (Dutch, 15??-1575). Françoise de Longwy, about 1527. Oil on panel; 14.6 x 11.7 cm (5 3/4 x 4 5/8 in). Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 19.764. Francis Bartlett Donation of 1912. Source: Museum of Fine Arts

Fig. 11 - Artist unknown. Claude of France, first wife of Francis I, 19th century. Watercolor on ivory. Honolulu: Honolulu Museum of Art, 6475.1. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The ideal

The fashion of the Renaissance period continues to gradually move away from the religious restrictions and modesty of the Middle Ages. The low-cut necklines that are so popular in the first half of the 16th century could symbolize a mixture of fertility and sensuality. The ideal woman was often pale with slightly pink cheeks, and a soft, round face. All of that can be seen in Anne de Piesseleu. No wonder she was considered an exceptionally beautiful woman.

Fig. 12 - François Clouet (French, ca.1510–1572). Anne de Pisseleu, 15??. Black chalk and sanguine on paper. Chantilly, France: Condé Museum. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Another portrait of Anne de Pisseleu by French painter François Clouet (Fig. 12) shows a very similar type of garment being worn. It again features a dark-colored bodice, large sleeves, lowered square neckline, and a French hood. Two necklaces complete her dress. Anne’s face looks plumper, and she is probably younger here.

Its Legacy

The fashion trends of the first part of the 16th century still inspire modern designers. While we don’t see looks that fully resemble costumes of the era, there are certain elements borrowed from that period:

- Square necklines arching slightly upwards. A number of ready-to-wear collections in the 2010s, including Valentino and Dolce & Gabbana, incorporated square necklines of the 16th century into their contemporary dresses (Figs. 13-14).

- Large bell-mouth sleeves. More recently Stephane Rolland’s Fall/Winter 2018 runway show featured a coat dress with large bell sleeves (Fig. 15).

- Large headbands worn on the back of the head. Contemporary accessories retailer Lele Sadoughi introduced large velvet headbands that can remind one of a simple French hood (Fig. 16).

Fig. 13 - Valentino. Ready-To-Wear Collection, Autumn/Winter 2013. Source: Vogue UK

Fig. 14 - Dolce & Gabbana. Ready-To-Wear Collection, Fall/Winter 2014. Source: Vogue Italia

Fig. 15 - Stephane Rolland. Haute Couture Collection, Fall/Winter 2018/2019. Source: Getty Images

Fig. 16 - Lele Sadoughi. , Fall 2018. Velvet. Source: Lele Sadoughi

References:

- “Attributed to Corneille de Lyon | Anne de Pisseleu (1508–1576), Duchesse d’Étampes” Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed November 1, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/435945.

- Blum, André Salomon, and Doris I Wilton. The Last Valois, 1515-90 … Translated from the French by D.I. Wilton. [With Plates]. George G. Harrap & Co.: London, 1951. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/557378586.

- Blunt, Anthony. The Art and Architecture in France, 1500-1700. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/442668455.

- Cassin-Scott, Jack. The Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Costume and Fashion: From 1066 to the Present. London; New York: Cassell Illustrated, 2006. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1023729733.

- Croizat, Yassana C. “‘Living Dolls’: François Ier Dresses His Women.” Renaissance Quarterly 60, No. 1 (2007): 94–130. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/5546125625.

- Desgardins, E. Anne de Pisseleu, duchesse d’Étampes et François Ier. Paris: H. Champion, 1904. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/866900023.

- Dubois de Groër, Anne. Corneille de La Haye dit Corneille de Lyon. Paris: Arthena, 1996. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/984055050.

- Hamel, Frank. Fair Women at Fontainebleau. London: E. Nash, 1909. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/613101741.

- Hayward, Maria. Rich Apparel: Clothing and the Law in Henry VIII’s England. Farnham (Surrey): Ashgate, 2009. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/638826197.

- Kelly, Francis Michael, and Randolph Schwabe. European Costume and Fashion, 1490-1790. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/962876571.

- Laver, James. Early Tudor, 1485-1558. London: Harrap, 1951. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/221369262.

- Palustre, Léon, and Société archéologique de Touraine. Album de l’exposition rétrospective de Tours (1890). Tours: Librairie L. Péricat, 1891. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1056303532.

- Perry, Michael, Ninya Mikhaila, Jane Malcolm-Davies, and Caroline Johnson. The Tudor Tailor: Reconstructing 16th-Century Dress. London: Batsford, 2006. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/475709430

- Ribeiro, Aileen, and Roy Strong. The Gallery of Fashion. London: National Portrait Gallery, 2000. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/611716597.

- Rouillard, Philippe. “Corneille de Lyon [Corneille de La Haye].” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University. Accessed November 1, 2018. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T019532.

- Ruppert, Jacques. Le Costume. Paris: Flammarion, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/462084313.

- Tortora, Phyllis, and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume. New York; London: Fairchild Books, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/990641691.