Diego Bemba’s 1643 portrait, along with those of Pedro Sunda and Don Miguel de Castro, represents an early example of cultural exchange in which African ambassadors donned European costume in order to project a carefully curated image of cultural capital.

About the Portrait

This gentle, solemn portrait of a young African aristocrat was painted in the Netherlands in the early 1640s by either Jaspar (before 1627-1647) or Jeronimus Beckx (life dates unknown). Both brothers were painters, but aside from the series of portraits discussed below, only one other painting by them is known (Fig. 1). The painting of Diego Bemba was previously attributed to Albert Eckhout, a painter for the Dutch colonial court in Brazil, but recent research has shown that a ‘Becx’ was paid for it in 1645 in Amsterdam (Kolfin 38).

There are two other portraits from the same set, part of what was originally a six-portrait series: one of Don Miguel de Castro (Fig. 2) and one of Pedro Sunda (Fig. 3) (Fromont 168). These three portraits are the only seventeenth-century Dutch portraits of Black sitters whose names are still known today (Kolfin 38). That is not to say, however, that there are no other portraits of Black Dutch men and women. There was a trend during this period of depicting Black people in tronies (‘faces’; think Girl with a Pearl Earring) as with the man in figure 4, and to paint Black people from life on city streets, as Rubens did with the man in figure 5. There was a small Black population in Amsterdam during this time, and historical evidence shows that while most scraped by, some were able to earn substantial amounts of money and lived well (Kolfin 17, de Winkel 63).

However, Pedro Sunda and his painted brothers were not Amsterdammers: they hailed from the province of Soyo in the kingdom of Kongo (today, western DRC and Angola), which had converted to Catholicism in the early sixteenth century and did substantial business with European countries. Kongo had been an ally of Portugal in the sixteenth century and in the seventeenth allied itself with the Dutch, including the Dutch colony in Brazil (Green 1).

In his book A Fistful of Shells: West Africa from the Rise of the Slave Trade to the Age of Revolution (2020), Toby Green describes the international luxury of Kongo’s court:

“The court of the Kongolese king was a luxurious affair, rich with carpets and tapestries from Flanders, cloths woven in India and silver-inlaid dining services and religious ornaments made from the orders of the New World.… Beyond the high-status foreign imports, the court was also filled with woven Kongo cloths inlaid with symbolic meanings, and the manikongo and his chief advisers wore strings of coral beads and red sashes in the Kongo style.” (Green 1)

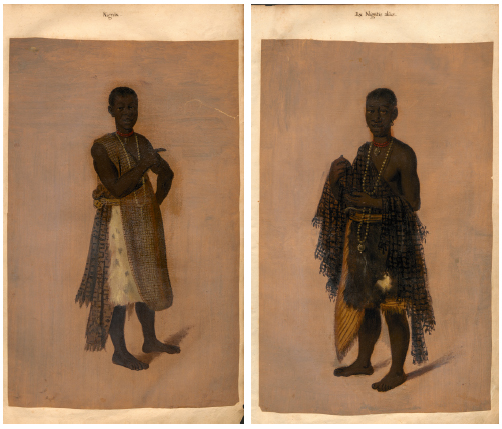

These three men were part of a five-person ambassadorial party headed by de Castro from Soyo to the Dutch colonial capital in Brazil (Fromont). There, they were painted by Albert Eckhout (for real this time) in what Green describes as dress “on their own terms”: red sashes of office, mpu (caps of office), and outfits that “symbolized power in the Kongo Court” (2). These ensembles can be seen in figures 6 and 7; the two men in figure 6 are most likely Pedro Sunda and our sitter Diego Bemba, “young men of the princely caste, the mwissikongo” (Green 1). (The Statens Museum labels them “servants,” a title that does not appear on other publications of these paintings.) The three older men in figure 7, all wearing raffia mpu (Fig. 8) are likely Miguel de Castro, Bastião de Sonho and António Fernandes, noble and highly educated ambassadors “who could converse with the Dutch officials in Latin” (Fromont).

After a stay in the capital Olinda, the party traveled across the ocean to Holland, where Beckx was then paid to paint them in European clothing. Just as de Castro is dressed more finely in his Kongolese garb as ambassador, his Dutch clothing is also more luxurious than the others, with several extra garments and accessories. Pedro Sunda and Diego Bemba were painted holding, respectively, an ivory tusk and a woven raffia box – objects “emblematic of the diplomatic exchanges between the Kongo and the Low Countries” (Fromont 166).

The clothing that de Castro wears is his own, a unique set that was gifted to him by the Dutch governor in Brazil (Kolfin 38). The young men, however, are wearing matching green suits with gold trim made in the European tradition of servant uniforms. Note that their Kongolese ensembles in figure 6 did not match each other; this change may have been because the Dutch did not understand their true roles in the envoy as mwissikongo, and it made more sense to Europeans to have attendants – even noble ones – in uniform.

In her book The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo (2017) Cécile Fromont explains that Don Miguel de Castro:

“almost certainly took an active role in the composition of the paintings… These representations of the diplomats in both European and Kongo finery underline how the African men put forward a public image that captivated Europeans with its flexible use of elite European dress as well as stunning and exotic African regalia.” (168)

Green, examining the portrayal of these Kongolese politicians in different types of clothing for European eyes, describes them as “adept at displaying the multiple languages of power” (2). And ‘power’ is the key word, as these portraits embody the colonial ties of the 17th-century Atlantic world. The Dutch were massively profiting off of the transatlantic slave trade in this era, and despite decrying the concept, Kongolese King Garcia II made transactions of enslaved people and continued the legacy of a kingdom that had been built on enslaving the people outside of it (Green 6). The Dutch and the Portuguese sliced Brazil up into colonies that effectively ran on enslaved labor, and Olinda, not Amsterdam, was the capital that the Kongolese envoy deemed most useful to travel to and ally with first (Marquese). And indeed, one of the gifts presented to the Dutch governor by Miguel de Castro and his party was two hundred enslaved people (Kolfin 38).

Slavery was technically illegal in the Netherlands at this time, but occurred nonetheless. While some Africans made their way willingly to Holland, most were brought there forcibly by way of Portugal, just as de Castro and Diego Bemba sailed two hundred people to Brazil (Archangel 74). Did the Kongolese envoys meet Black Amsterdammers and understand the circumstances that had brought them there – a system in which they were complicit?

Fig. 1 - Jeronimus Beckx (II) (Dutch). The Arms of the Dutch East India Company and of the Town of Batavia, 1651. Oil on panel; 63 × 97 cm. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, SK-A-4643. Source: Rijksmuseum

Fig. 2 - Jaspar Beckx (Dutch, before 1627-1647). Don Miguel de Castro, Emissary of Kongo, 1643. Oil on panel; 75 x 62 cm. Copenhagen: Statens Museum for Kunst, KMS7. Source: SMK

Fig. 3 - Jaspar Beckx (Dutch, before 1627-1647). Pedro Sunda, a Servant of Dom Miguel de Castro, 1643. Oil on panel; 75 x 62 cm. Copenhagen: Statens Museum for Kunst, KMS8. Source: SMK

Fig. 4 - Govert Flinck (Dutch, 1615-1660). Head of a Black Man, ca. 1640. Oil on wood; 27.5 x 21 cm. Barcelona: Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, 065003-000. Francesc Cambó Bequest, 1949. Source: MNAC

Fig. 5 - Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577-1640). Four Studies of a Black Man, ca. 1615. Oil on canvas transferred from wood; 51 x 66 cm (20 x 25.9 in). Brussels: Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, 3176. Source: KMSK

Fig. 6 - Albert Eckhout (Dutch, c. 1610–1665). Portrait of Kongo Ambassadors to Recife, ca. 1637-1644. Oil on paper; 30 x 50 each cm. Krakow: Jagiellonian Library, Libri Picturati 34, folio 9 and 11. Photograph courtesy of the Jagiellonian Library Photographic Services. Source: SciELO

Fig. 7 - Albert Eckhout (Dutch, c. 1610–1665). Portrait of Kongo Ambassadors to Recife, ca. 1637-1644. Oil on paper; 30 x 50 each cm. Krakow: Jagiellonian Library, Libri Picturati 34, folio 1, 3, 5. Photograph courtesy of the Jagiellonian Library Photographic Services. Source: SciELO

Fig. 8 - Designer unknown (Kongolese). Hat (Mpu), Late 19th century. Fiber; 22.9 x 13 x 13 cm (9 x 5 1/8 x 5 1/8 in). New York: Brooklyn Museum, 22.1610. Source: BM

These paintings represent important men in unusual circumstances, who travelled halfway around the world in pursuit of political gain, and they are a “testament to the diplomatic reach of the Kongo kings in the 1640s” as well as the complex and dark colonial history of the Atlantic empires (Green 7).

Jaspar Beckx (Dutch, before 1627–1647). Diego Bemba, a Servant of Dom Miguel de Castro, 1643. Oil on panel; 75 x 62 cm (29.5 x 24.4 in). Copenhagen: Statens Museum for Kunst, KMS9. Source: SMK

About the Fashion

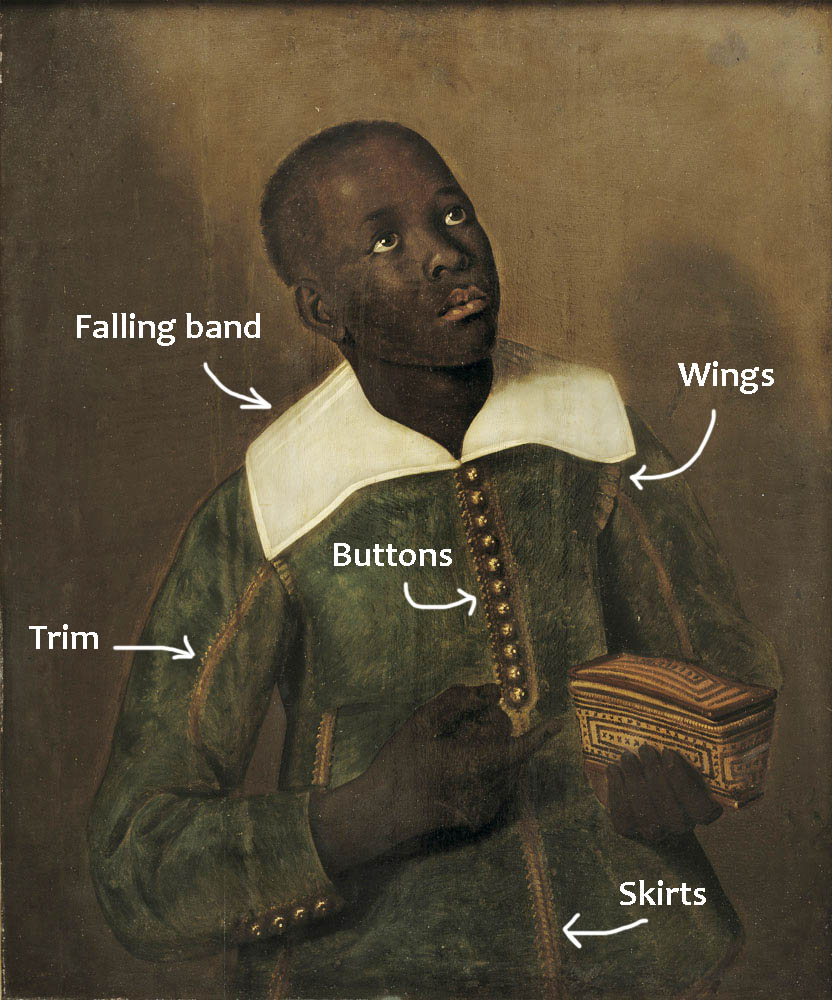

Diego Bemba’s clothes are fine but simple. He–like fellow young aristocrat Pedro Sunda (Fig. 3)–is wearing a green doublet with shimmering gold trim and buttons, topped with a large white collar.

In their book Clothing Through American History: The British Colonial Era (2013), Kathleen Staples and Madelyn Shaw describe the evolution in doublets during this time:

“By the 1630s doublets became even higher waisted; the waist, while still pointed, had straightened…The skirt now reached hip level, with two or three wider tabs on each side.

By the early 1640s the doublet had changed significantly. The skirt generally was cut in one with the upper body although two long tabs stitched front and back to the doublet body gave an alternate styling. This cut eliminated both the distinct waist line and points and bow-knots. The garment still buttoned down the center front; but certain styles fastened only to mid-chest, leaving a wide inverted V of shirt exposed beneath.” (298)

This exceptionally high waist of the 1640s, seen in figure 9, is visible in both green doublets and is paired with very long, wide front skirts. It looks like one has a seam at the waist and the other does not, which is unlikely to have been the case. If there is a seam, then along with the small wings at the shoulders, their clothing has a slightly earlier feel. It is possible that while de Castro’s garments were specially made, the younger mens’ clothing was pulled from the servants’ wardrobe of the people whom they were visiting. Servants often wore matching uniforms called livery in the colors of the family they served (Fig. 10) (Cumming 122). For these clothes to be borrowed livery would not only explain why the two match so neatly but also why their sleeves seem to be a tad short. It is possible, though, that the suits were made ahead of time for the men in the tradition of livery and ended up slightly ill-fitted.

Their doublets are not precisely in fashion for 1643. As Staples and Shaw describe, doublets had begun to be cut all in one at the front and often exposed the shirt underneath with some form of slashing, paning, or separation. Compare their silhouettes with the clothing in figures 9 and 11.

Green and gold were certainly not in mainstream Dutch fashion either, which was holding strong in its love affair with black (Fig. 12). In Costume and Fashion: A Concise History (2002), James Laver describes Dutch style in this era:

“Holland was ruled by a prosperous bourgeoisie, a body of influential and pious merchants and magistrates known as regents. They wore a distinctive costume of conservative cut and black in hue…” (108)

Fig. 9 - Benjamin Block (attr.) (German, 1631-1690). Albrecht von Brandenburg-Ansbach, 1643. Kulmbach: Der Plassenberg. Photo André Karwath. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown (Swedish). Doublet (page livery), 1611-1632. Yellow silk atlas, linen and silk lining; front length 54 cm. Stockholm: Livrustkammaren, 19016 (3599). Source: LSH

Fig. 11 - Designer unknown (Swedish). Ensemble of Karl X Gustav, 1647. Wool, linen, silk; waist 116 cm. Stockholm: Livrustkammaren, 19339 (3416:b). Source: LSH

Fig. 12 - Frans Hals (Dutch, 1582/3-1666). Regents of the St. Elisabeth's Hospital, Haarlem, 1641. Oil on canvas; 153 x 252 cm (60.2 x 99.2 in). Haarlem: Frans Hals Museum, os I-114. Source: FHM

Fig. 13 - Hendrick Cornelisz van Vliet (Dutch, 1611/12-1675). Portrait of Michiel van der Dussen and His Family, 1640. Oil on canvas; 159 x 210 cm (62.5 x 82.6 in). Delft Municipal Museums. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Children wore other colors (Fig. 13), as did servants, common people and unmarried men. Married Dutch men of importance during the mid-seventeenth century were typically painted in black clothing, making these two – and to a certain extent, de Castro – stand out. It may be that Diego Bemba was unmarried.

The material of these green doublets is a mystery, as the fabric is not carefully rendered; it could be wool or silk. Many extant doublets with such high-quality trim and buttons are made of silk (Fig. 14). The trim is made of metal-wrapped thread, either gold or silver-gilt, and the buttons are wrapped in the same thread carefully to create small patterns.

Other countries were not as strictly bound to the same black clothing as the Dutch; an extant British suit in figure 15 gives a better idea of what a full silk ensemble might look like in the late 1630s. Notice the stiff collar and the pronounced curve and taper of the sleeves. The bows (points) at the waist of the doublet are either attachment points to which the breeches are tied to in order to stay up, or vestigial and decorative – there may be hooks and eyes on the inside of the garment for the same purpose (Doering 35).

While we cannot see Diego Bemba’s or Pedro Sunda’s lower half, we may presume that they are wearing similar-looking breeches (or possibly Venetians or slops, given the earlier and simpler look of their clothing) as well as stockings and latchet shoes (Fig. 13) (Doering 35).

In Costumes of Everyday Life: An Illustrated History of Working Clothes from 900 to 1910 (1972), Margot Lister describes these early modern pants:

“Venetians, worn as practical dress, were not heavily padded on the hips but were plain breeches fastening below the knees. They were worn between 1600 and 1610 and again in the 1640s.” (80)

Underneath his ensemble, Diego Bemba is likely wearing a shirt and a pair of drawers made of white linen to protect his doublet and breeches from body oil and sweat (Staples 302). His shirt was probably similar to the one in figure 16; the basic cut of such garments remained the same for most of the century and only differed in decoration.

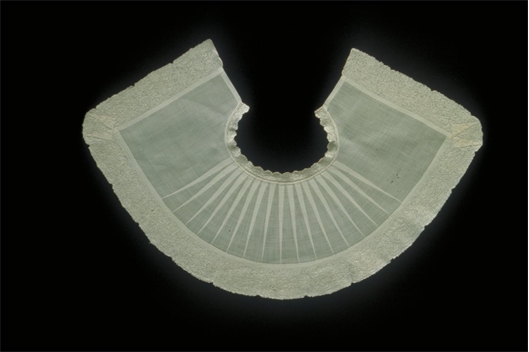

To complete the look, both men are wearing white linen falling bands with careful darts. The hems are visibly more opaque than the rest of the garment, implying fineness and transparency of material. However, neither of them has a falling band quite so stiffly starched as Miguel de Castro’s, which also has additional darts at the neck for both shaping and luxury like the one in figure 17 (Staples 304). This is a subtle way in which his elevated status is identified, beyond the obvious feathered hat and brocaded silk doublet. Ruffs were no longer worn by most Europeans after about 1620, but the Dutch stubbornly held on to them for decades beyond that point (Staples 304). Dutch group portraits from this time period often show sitters with a mix of neckwear (Figs. 12-13).

One aspect of Diego Bemba’s dress that stands out is his lack of cuffs. See figures 9, 12, and 13; matching linen cuffs were worn by all those who could afford it, and turned back over the sleeve to display fine edgings of lace (Staples 305). The more transparent the linen, the better; the sheerness of a good-quality collar can be seen on the man in figure 18, whose white falling band suddenly turns red where it lies over his jerkin, and whose white linen cuffs are tinged rather gray in appearance over his black sleeves.

Diego Bemba’s hair also stands out, but only in a international European sense: In England and France, hairstyles were “rather flat on the top of the head, but frizzed out at the sides in thick curls” (Fig. 9) (Laver 107). But as with color and neckwear, the Dutch enjoyed different fashions, and many men in Holland preferred to keep their hair quite short (Laver 109). This national trend may explain why the men in figures 4 and 5 have close-cropped hair. Diego Bemba and Pedro Sunda may have kept the hairstyles they preferred from Kongo for the whole journey, as their hair is also very short in the paintings in figure 6.

Many European men in this era also wore facial hair, the Dutch included (Fig. 12). But as with hair on the head, members of the envoy clearly made the decision not to engage in every act of European style – merely those that could easily be taken on and off.

Besides the lack of cuffs and the matching clothing, the last aspect of dress that signifies these two may not be gentlemen in Dutch eyes is the lack of hat (Fig. 19). In Fashion: The Definitive Visual Guide (2019), Kathryn Hennessy describes headwear in the period 1635-1649:

“The ‘sugarloaf’ hat with a high crown and narrower brim was popular along with the ‘cocked’ hat which had a shorter crown and wide brim, worn at an angle. The finest hats were made of beaver pelts imported from North America.” (123)

“Hats were often decorated with trailing feathers such as ostrich plumes. These were placed on the left side of the hat leaving the right sword-arm free to move. Worn indoors, hats were removed before royalty and elders.” (122)

In the end, the way that Diego Bemba and Pedro Sunda are dressed seems to demote them from the aristocratic status that they held in their homeland. They are labeled as servants in these paintings, both literally and visually, and perhaps either did not understand or did not care about the visual cues that a Dutch audience would have known to look for.

Fig. 14 - Designer unknown (German). Man's doublet (detail), ca. 1610-20. Riggisberg: Abegg Stiftung. Collection Baron von Hüpsch. Source: Swissinfo.ch

Fig. 15 - Designer unknown (British). Doublet & breeches, 1630-40. Satin, stamped, lined with linen and buckram, trimmed with braid and silk ribbon, hand-sewn. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 348&A-1905. Source: VAM

Fig. 16 - Philippe de Champaigne (French, 1602-1674). Antoine Singlin, ca. 1646. Oil on canvas; 79.1 × 65.1 cm (31 1/8 × 25 5/8 in). Los Angeles: The Getty, 87.PA.3. Source: Getty

Fig. 17 - Designer unknown. Collar (men), ca. 1660. White linen batiste, linen bobbin lace; 6 cm wide bobbin lace; 18 cm wide. Swiss National Museum, State Museum Zurich, IN-8759.a. Purchase. Source: SNM

Fig. 18 - Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (Spanish, 1599-1660). El Primo, 1644. Oil on canvas; 106.5x 82.5 cm (41.9 x 32.4 in). Madrid: Museo del Prado, P001202. Source: MdP

Fig. 19 - Designer unknown (British). Hat, 1590-1670. Black beaver fur, felted and blocked; height 17.2 cm. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.22-1938. Given by Lady Spickernell. Source: VAM

Diagram of referenced dress features. Source: Author

Its Legacy

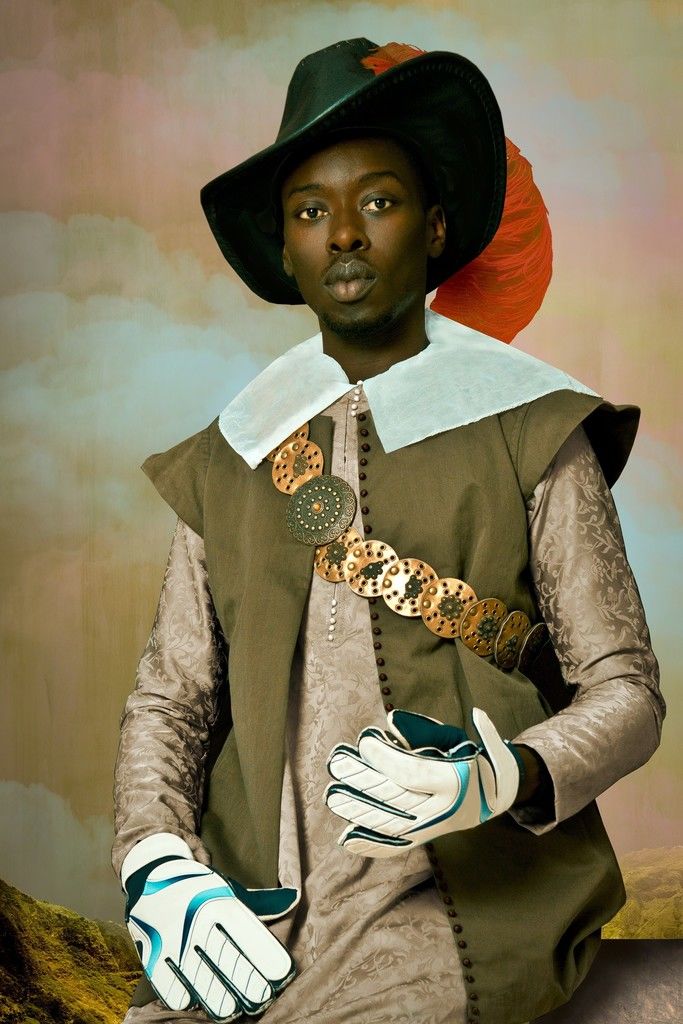

The portraits of members of the 1643 Kongolese envoy, especially that of Miguel de Castro, have inspired several works of art.

In 2015, Senegalese artist Omar Victor Diop showed his work “Project Diaspora” (Fig. 20) at the London art fair 1:54. Artsy’s Art Genome Project describes the piece:

“The portrait’s costume and composition appropriate that of Castro’s official portrait from this journey… although Diop adds the gloves of a soccer goalie—referencing a different form of diplomatic gamesmanship, that of African soccer players residing in Europe.”

Fig. 20 - Omar Victor Diop (Senegalese). Don Miguel de Castro, Série Diaspora, 2014. Source: Artsy

During the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, singer, writer, and presenter Peter Braithwaite visited the Dutch portraits of Miguel de Castro, Diego Bemba, and Pedro Sunda virtually and recreated their clothing with whatever he could find in his home, including crackers (Fig. 21). While his work has humorous elements, it is important: he is enabling the public to discover dozens of portraits of Black sitters throughout history that are rarely discussed.

References:

- The Art Genome Project. “5 Trends at 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair.” Artsy, 15 May 2015. Accessed 4 July 2020. https://www.artsy.net/article/the-art-genome-project-5-trends-at-1-54-contemporary-african-art-fair-2015

- Cumming, Valerie, Phillis Cunnington, and C. Willett Cunnington. The Dictionary of Fashion History. Oxford: Berg, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/751449764

- Doering, Mary D. “Breeches and Hose, 1600-1714.” In Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe. José Blanco, Mary D. Doering, Patricia Hunt-Hurst, and Heather Vaughan Lee, eds. Santa Barbara, California : ABC-CLIO, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/904505699

- Fromont, Cécile. The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1105745204

- Fromont, Cécile. “Foreign Cloth, Local Habits: Clothing, Regalia, and the Art of Conversion in the Early Modern Kingdom of Kongo.” Anais do Museu Paulista: História e Cultura Material 25, no. 2 (2017): 11-31. SciELO

- Green, Toby. A Fistful of Shells: West Africa from the Rise of the Slave Trade to the Age of Revolution. London: Penguin Books, 2020. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1153169486

- Hennessy, Kathryn. Fashion: The Definitive Visual Guide. New York: DK Publishing, 2019. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1142142991

- Laver, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/440744982

- Lister, Margot. Costumes of Everyday Life: An Illustrated History of Working Clothes from 900 to 1910. London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1972. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/958999886

- Marquese, Rafael de Bivar, & Doyle, Anthony. “The Dynamics of Slavery in Brazil: Resistance, the slave trade and manumission in the 17th to 19th centuries.” Novos Estudos – CEBRAP 2 (2006). SciELO

- Archangel, Stephanie, Elmer Kolfin, Mark Ponte, and Marieke de Winkel. Black in Rembrandt’s Time. Zwolle: WBOOKS, 2020. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1137196444

- Staples, Kathleen, and Madelyn Shaw. Clothing Through American History: The British Colonial Era. Westport: ABC-CLIO, 2014. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1058991877