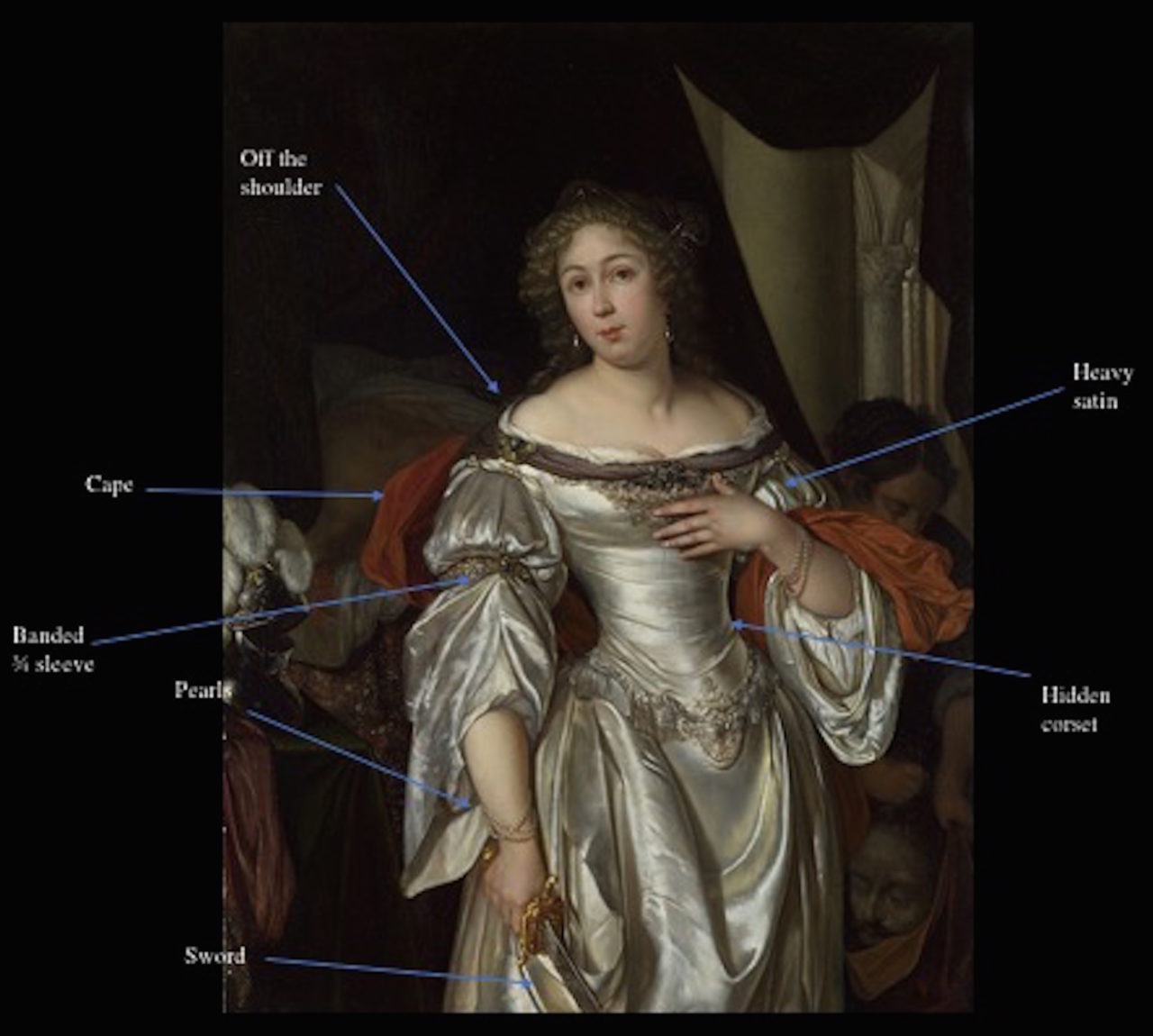

Van der Neer’s Judith represents a 17th-century vision of a biblical character and is full of ravishing contemporary fashion detail.

About the Artwork

E glon Hendrick van der Neer was a Dutch painter from Amsterdam born in 1635. L. B. L. Harwood and Marjorie Wieseman detail in their biography of van der Neer that he was part of the Dutch Golden Age and Baroque era. They further note he was one of the few artists known to incorporate symbolic meaning into his genre paintings and was known for modern scenes with a sophisticated veneer, including stylish ‘French’ costume and architecture. Van der Neer began working on history paintings in the 1670s. Judith was one of his paintings where he focused on single figure set close to the picture plane; she appears in what Harwood and Wieseman call contemporary ‘allegorical’ dress (Oxford Art Online). Wikipedia offers a brief background on Judith:

“A daring and beautiful widow, who is upset with her Jewish countrymen for not trusting God to deliver them from their foreign conquerors. She goes with her loyal maid to the camp of the enemy general, Holofernes, with whom she slowly ingratiates herself, promising him information on the Israelites. Gaining his trust, she is allowed access to his tent one night as he lies in a drunken stupor. She decapitates him, then takes his head back to her fearful countrymen. The Assyrians, having lost their leader, disperse, and Israel is saved. Though she is courted by many, Judith remains unmarried for the rest of her life.”

In this portrait, the body of Holofernes lies on the bed and the maid puts his head into a sack. As the National Gallery notes, the prominence of the figure, the highly specific characterization of her face and dress, and the subsidiary position of the maid and the head of Holofernes make it likely that this is a portrait of a young woman in the guise of the Jewish heroine.

Eglon van der Neer (Dutch, 1634–1703). Judith, 1678. Oil on oak; 32 x 24.6 cm (12.6 x 9.7 in). London: National Gallery, NG2535. Salting Bequest. Source: National Gallery

About the Fashion

The overarching fashion of the 1670s was inspired by many prominent women, usually the “current mistress of the king,” according to Doreen Yarwood in Fashion in the Western World, 1500-1990 (50-51). Queen Henrietta Maria (Fig. 1) was, in particular, known for her trend-setting fashionability. Judith’s dress seems to take inspiration from the earlier queen, who in van Dyck’s portrait is also shown wearing a very low-cut satin bodice, with exposed cleavage, and a gathered sleeve. By the 1670s, as Jack Cassin-Scott and Ruth M Green note in Costume and Fashion in Colour, 1550-1760, “the feminine gown had a close-fitting, boned bodice which, because of the longer waist, dipped to a deep point in the front, creating a slimmer look” (200). Van der Neer took this into account as he put Judith into a very slim-fitting gown. Giving her that very hour glass figure was a most likely a corset that is not visible in the painting.

A sketch by artist Sir Peter Lely (Fig. 2) displays the neckline typical of fashion around this time when necklines were cut low, almost straight across and slightly off the shoulder. As Phyllis Tortora and Keith Eubank note in Survey of Historic Costume: A History of Western Dress (2000), heavy satin fabrics were popular for formal dresses like that Judith wears(214). A formal satin gown seems visually appropriate for the occasion (if impractical in practice): What could look better than to seduce an enemy leader and claim his head than a dress that glistens like the sword she is holding? Also during this time, undergarments such as the chemise were worn and were visible on the edge of the neckline and sleeve (Tortora/Eubank 214). Sir Peter Lely’s portrait of the Duchess of Portsmouth (Fig. 3) and Van der Neer’s Judith both copy this trend.

Scarfs and shawls are very popular during this time period because of the exposed décolletage (Cassin-Scott 200). Joan Carlile’s depiction of an unknown lady (Fig. 4) has a scarf wrapped around one arm with the rest floating behind her. Similarly, Van der Neer has a portion of a red scarf wrapped around Judith’s left hand with the majority behind her. Sleeves during this time “were set low on the shoulder, opening into a full puff that ended below the elbow” (Tortora/Marketti 259). The sleeves on Judith follow this style clearly exposing her forearms with her actual sleeve banded and overflowing. The sleeve seems similar to the leg-of-mutton sleeve popular during this century, but slightly deflated. Van der Neer kept it in the same realm as other women during the time, but by choosing to band it he creates an even bigger emphasis on the arm holding the sword.

Pearls are commonly seen on portrait of wealthy and prominent women in this time. Queen Mary II (Fig. 5) is shown wearing them around her neck and even attached to her gown; we see them also in the portraits of Queen Henrietta Maria (Fig. 1) and Joan Carlile’s painting (Fig. 4). Judith is also shown with pearls, but only at her wrist and in her elaborately dressed hair. Another commonality between Judith and the other ladies (Figs. 1-5) during this time period is her hairstyle. The popular hairstyle during this period was the chignon at the back of the head with a parted set of curls surrounding the front of the face. In addition to her hair, “from 1660 – 1700, some women placed plumpers, small balls of wax, in the cheeks to give the face a fashionable rounded face” (Tortora- Marketti 259). This is a trend van der Neer also seemed to adopt for the look of Judith and to give her a contemporary look.

Fig. 1 - Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, 1599-1641). Queen Henrietta Maria, 1633. Oil on canvas; 79 x 48.7 cm (31.1 x 19.2 in). Melrose: Abbotsford House, T.AT.3177. Source: Art UK

Fig. 2 - Sir Peter Lely (Dutch, 1618-1680). Portrait of a Lady, undated. London: Royal Collection, 913255. Source: Royal Collection

Fig. 3 - Sir Peter Lely (Dutch, 1618-1680). Portrait of Louise de Keroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth, 1671-1674. Oil on canvas; 125.1 × 101.6 cm (49 1/4 × 40 in). Los Angeles: Getty Museum, 78.PA.223. Source: Getty

Fig. 4 - Joan Carlile (English, 1606-1679). Portrait of an Unknown Lady, 1650-55. Oil on canvas; 110.7 x 90 cm (43.6 x 35.4 in). London: Tate, T14495. Source: Tate

Fig. 5 - Sir Peter Lely (Dutch, 1618- 1680). Mary II, 1677. Oil on canvas; 126.0 x 102.3 cm (49.6 x 40.3 in). London: Royal Collection, 402587. Source: Royal Collection

Its Legacy

Vivienne Westwood took inspiration from the 17th century for her 2013 Fall/Winter Ready-to-wear Collection. Figure 6 features a white silk dress that follows cues from the 1670s’ low-cut bodice, long-pointed torso and shortened sleeves.

Fig. 6 - Vivienne Westwood (English, 1941-). Vivienne Westwood, Fall/Winter 2013. Source: Daily Mail

References:

-

“Book of Judith.” Wikipedia, November 24, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Book_of_Judith&oldid=811789018.

- Cassin-Scott, Jack, and Ruth M Green. Costume and Fashion in Colour, 1550-1760. Poole: Blandford Press, 1975. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1008514181.

- “Eglon Hendrik van Der Neer | Judith | NG2535 | National Gallery, London.” Accessed November 10, 2017. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/eglon-hendrik-van-der-neer-judith.

- Harwood, L. B. L. and Wieseman, Marjorie E. “Neer, van der.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed November 10, 2017, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T061585pg2.

- Tortora, Phyllis G, and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume: A History of Western Dress. New York: Fairchild Publications, 2000. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1008328889.

- Tortora, Phyllis G, and Sara B Marcketti. Survey of Historic Costume. New York: Fairchild Books, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/893721552.

- Yarwood, Doreen. Fashion in the Western World, 1500-1990. London: Batsford, 1992. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1008095298.