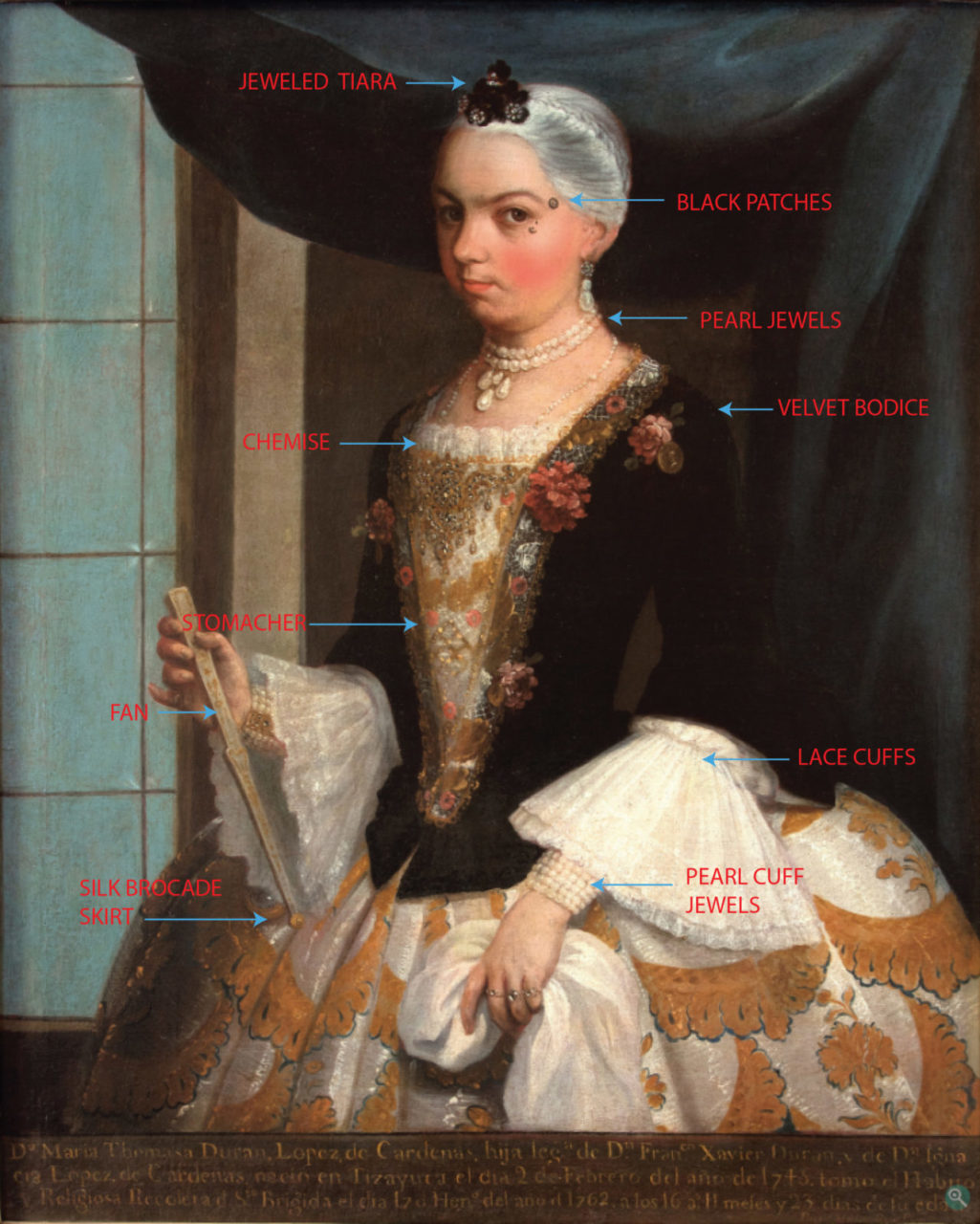

The black fabric that tones down Doña Maria Tomasa Durán López de Cárdenas’ extravagant dress, along with the religious subtext of her portrait, demonstrate the subtle differences that the fashions of New Spain had with those of Europe.

About the Portrait

A

t the time of this portrait, Doña Maria Tomasa Durán López de Cárdenas was sixteen years old and about to enter the convent of Santa Brigida. She was born in the city of Tizayuca in the state of Hidalgo in Mexico around 1746 to Don Francisco Javier Duran y Doña Ignacia López de Cardenas.

Eighteenth-century art in Mexico was often religious, and there were traditions unique to New Spain concerning young women entering the convent. One in particular was to “make two portraits of the young women who would enter the convent; in the first the young girl was dressed ‘in the century’ all of them in a very rich and extreme frivolous dress” (Armella de Aspe 77). Presumably, the second would show the girl in her conservative habit. This genre of religious portraiture reached its peak during the second half of the eighteenth century.

A similar portrait of a young woman (Fig. 1) shows Doña Ignacia de Arozqueta y de las Heras at seventeen years of age with luxurious clothing, sparkling jewels, and an elegant, fashionable hairstyle, just prior to entering the convent of Jesus Maria (Armella de Aspe 77). These two eighteenth-century portraits showcase the sense of luxury and lavish fashion choices inspired by colonial Spanish costume, a last chance for the young woman to be immortalized in the wealth of her family. But the convent was hardly a hiding place for girls who couldn’t be married; the Metropolitan Museum of Art describes how “being admitted to a convent was a badge of honor among New Spain’s elite.” These portraits not only proved the wealth of Latin American families, but entered them into a continuing lineage of respectability connected to religious service.

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown. Doña Ignacia de Arozqueta y de las Heras, 1720. Oil on canvas. Source: La Historia de Mexico a traves de la Indumenteria, pg. 76

Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz (Mexican, 1713–1772). Portrait of Doña Maria Tomasa Durán López de Cárdenas, 1762. Oil on canvas; 102.1 × 84.3 cm (40 3/16 × 33 3/16 in). Galería Coloniart, Collection of Felipe Siegel, Anna and Andrés Siegel, Mexico City. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

About the Fashion

Doña Tomasa wears what was traditional of young women in New Spain: a cut-away bodice, possibly of black velvet, with a stomacher that matches the fabric of her skirt. Lavish patterned textiles and solid black garments were highly favored in Spanish fashion.

Figure 2 is another example of this style from the late 1770s; we see the sitter in a black silk bodice with what appears to be a type of transparent fichu, or neckerchief, resembling a partlet from the previous era. Note that by the latter half of the eighteenth century, the stomacher had vanished from New Spain’s fashionable dress. Instead, bodices closed at center front. While the fabric of this sitter’s bodice is plain, it is decorated with white fabric rosettes, and the lace of her engageantes matches the delicate work on her fichu, perhaps imported from Milan or Flanders (Armella de Aspe 77).

Doña Tomasa’s 1760s gown, on the other hand, has an elaborate triangular stomacher with large and small flowers decorating it and spreading along the robings of the black bodice. The top half of her stomacher is decorated with gold jewelry covered in precious stones, common in New Spanish fashion. She also wears a brocaded silk skirt, which may have been imported from France, England, or even China, all centers of silk weaving (Armella de Aspe 77). Figures 3 and 4 show the variation in the trend of brightly colored silk. Note the young woman c. 1760 (Fig. 3) wearing a similarly large-patterned, brocaded gold and white fabric as Doña Tomasa does, though with a different figural pattern. A young lady in 1746 (Fig. 4) donned a rich red brocaded floral-patterned silk for her matching ensemble, complete with small, subtle stomacher. Doña Tomasa’s clothing drew inspiration and style from different regions of Europe and Asia, but certain details solidify the look as being specifically from New Spain.

Undergarments were important to achieving Doña Tomasa’s look in this portrait. Her chemise was essential; these elaborate dresses could not easily be cleaned, and longevity of precious and expensive garments was important. Even if a dress went out of fashion, its fabric could be repurposed in a decade or even a century for a new gown. Over top of her chemise, she is wearing a pair of formal, fully-boned stays, possibly covered in silk, to give the conical shape to her torso and provide good posture. The fullness and width of her skirt also indicates that she is wearing supports underneath her petticoats to achieve this look. She is probably wearing panniers, a cage-like under-structure made of whalebone (baleen), cane, or metal that provided width to the hips. For a less formal occasion, she could wear a bum roll or split bum instead, which was a padded roll or bag tied at the waist that would hold a woman’s skirt out from the body and mimicked the look of a large derrière.

When it comes to accessorizing, Doña Tomasa undoubtedly has one of the best looks recorded in the portraiture of New Spain. The decorative black patches worn on her temples and high cheekbones are beauty marks, known as mouches in French and chiqueadors in Spanish, and were often made of satin or velvet (Kaplan). Doña Tomasa’s are intricate and unique: decorative shapes of a sun, moon, and stars. It is more usual to see chiqueadors of a plainer variety; the sitter in figure 3 has placed three circular pieces of varying size near her left eye.

The young woman in figure 5 shares a similar headdress with Doña Tomasa; these decorations resemble a tiara and are made of what appears to be black fabric – again, a Spanish fashion – decorated with jewels and precious metals. Doña Tomasa, along with the sitters in figures 3 and 5, kept similar hygiene practices to her mainland European sisters of the decade: she wore her hair pomaded, powdered, and in a simple style close to the head. The high, heavily adorned hairstyles of pre-Revolutionary France were not yet in fashion, but at any rate, the women of New Spain generally kept less extravagant hairstyles than their French counterparts.

Fig. 2 - Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz (Mexican, 1713-1770). Portrait of María Ana Gertrudis Cabrera y Solano, 1778. Mexico City: Collection of Felipe Siegel, Anna and Andrés Siegel. Source: LACMA

Fig. 3 - Miguel Cabrera (Mexican, 1695-1768). Doña María de la Luz Padilla y Gómez de Cervantes, 1760. Oil on canvas; 109.2 x 83.8 cm (43 x 33 in). New York: Brooklyn Museum, 52.166.4. Museum Collection Fund and Dick S. Ramsay Fund. Source: Brooklyn Museum

Fig. 4 - Fray Miguel de Herrera (Mexican, 1729-1780). Doña María Josefa de Aldaco y Fagoaga, 1746. Oil on canvas; 179 x 129 cm (70.47 x 50.79 in). Mexico City: Museo Nacional de Historia, 10-230272. Source: INAH

Fig. 5 - Miguel Cabrera (Mexican, 1715 - 1768). Portrait of María Bárbara Guadalupe de Ovando y Rivadeneyra with Guardian Angel, 1760. Oil on canvas; 120 × 73 cm (47.25 × 28.75 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Private Collection. Source: MMA

Another detail of this portrait of Doña Tomasa concerns the amount of pearls that she is wearing. New Spain had an abundance of pearls harvested from what is now southern California, and after the conquest of Cortes, “pearl ornaments were lavishly worn; as well as forming necklaces, they used earrings and bracelets; Bracelets were carried on both arms and the number of threads reached a dozen” (Carrillo y Gariel 145). Randall notes that lace and jewels are prominent in portraits of women of all ages commemorating their entry into the convents (16). The jewels in which they were adorned generally belonged to the family and were not the property of the sitter.

The accessories, pose, and attire always illustrate the social standing of the sitter, all of whom depicted here had families with high positions in the viceregal government. Even her fan serves as a marker of her status: like the one in figure 2, it is closed and pointed to her right, which indicates her forthcoming introduction to the convent.

Translations by the author.

Its Legacy

In the spring of 2015, Dolce & Gabbana presented a collection that featured many trends and silhouettes prominent in eighteenth century New Spain. Throughout the collection, we saw an abundance of fitted, adorned bodices, full brocaded skirts, lace, jewels, and religious components, demonstrating that the fashions of Doña Tomasa’s culture and era continue to influence the world today (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6 - Dolce & Gabbana (Italian). Valery Kaufman modeling ready-to-wear on the runway, Spring 2015. Photograph by Yannis Vlamos. Source: Vogue

References:

- Armella de Aspe, Virginia, Teresa Castelló Yturbide, and Ignacio Borja Martínez. La Historia de México a Través de la Indumentaria. México: Inversora Bursátil, 1998. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/651574172

- Carrillo y Gariel, Abelardo. El Traje en la Nueva España. México: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1959. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/33169360.

- Kaplan, Rachel. “Beauty in the Eye of the Beholder: Fashion in 18th-Century Mexico.” LACMA Unframed, Feb 1, 2018. Accessed November 14, 2018. https://unframed.lacma.org/2018/02/01/beauty-eye-beholder-fashion-18th-century-mexico