Vigée Le Brun’s infamous portrait of Marie Antoinette embodies the tension between fashion and politics in 18th-century France.

About the Portrait

É

lisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1824) was a French painter active between 1775-1825. Her style, which attracted royalty and aristocrats across Europe, eventually became associated with that the tastes of Marie Antoinette and the ancien régime (Nicholson). She first painted Marie Antoinette in 1778 and became her official court painter shortly thereafter, painting about 30 portraits of Antoinette (Château de Versailles). With the intervention of the Queen, Vigée Le Brun was granted admission into the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in 1783–the same year that Vigée Le Brun painted Marie Antoinette in a Chemise Dress (Nicholson).

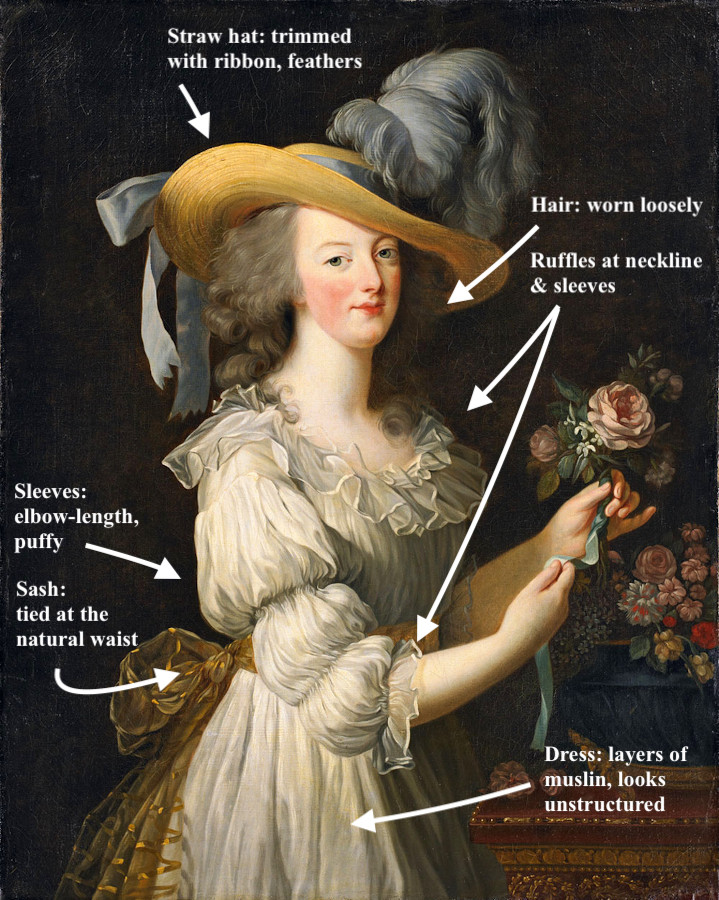

The three-quarter-length portrait depicts Marie Antoinette arranging flowers. She wears a large straw hat, trimmed with a gray ribbon and matching feather; underneath her hat, her hair is coming loose from its curled style, and a few curls fall to her shoulders. Most notable, however, is her dress: she wears a loose muslin dress, which is tied at her natural waist with a wide yellow sash, and features puffy elbow-length sleeves and frills along the neckline. This style of dress is the robe en chemise, and caused enough of an uproar that it was removed from the Salon of 1783 (The Met).

The robe en chemise represented two equally grave sins: first, it was made of imported cotton muslin, and not French Lyonnaise silk, which was considered unpatriotic. Second, it was significantly more relaxed than the fashions usually seen in official portraits, and appeared to be closer to contemporary undergarments than an appropriate ensemble (Steele 39). Though Vigée Le Brun had painted herself wearing a variation on the robe en chemise in 1782, the style was not yet acceptable for a Queen in an official portrait (Fig. 1). Since the reign of Louis XIV, luxurious fashion symbolized France’s power as an arbiter of politics and taste (Kawamura). Here, however, Marie Antoinette has forgone any of the usual markers of luxury, and by extension, markers of French power. After its removal from the Salon, it was replaced with one of Vigée Le Brun’s more classic portraits of the Queen, Marie Antoinette with a Rose (Fig. 2). In this portrait, Marie Antoinette holds the same pose, but is dressed in a formal silk robe à la française, trimmed with lace and a bow. She wears a pearl necklace and corresponding bracelets; the ensemble is completed with freshly styled hair and a fabric hat with three feathers.

Fig. 1 - Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (French, 1755-1842). Self Portrait in a Straw Hat, 1782. Oil on canvas; 97.8 x 70.5 cm (38 1/2 x 27 3/4 in). London: The National Gallery, NG1653. Bought, 1897. Source: The National Gallery

Fig. 2 - Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (French, 1755–1842). Marie Antoinette with a Rose, 1783. Oil on canvas; 116.8 × 88.9 cm (46 × 35 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Lynda and Stewart Resnick. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (French, 1752-1842). Marie Antoinette in a Chemise Dress, 1783. Oil on canvas; 35 3/8 x 28 3/8 in. (89.8 x 72 cm). Kronberg: Hessische Hausstiftung. Source: The Met

About the Fashion

The robe en chemise, also known as the chemise à la reine, became the foremost fashion by the end of the 18th century. Tortora notes that it “resembled the chemise undergarment of the period, but unlike the chemise, had a waistline and a soft, fully gathered skirt” (289). The robe en chemise usually featured long sleeves that could be gathered in small puffs, as seen in Marie Antoinette’s portrait. The gown itself was largely unadorned; the muslin fabric was not patterned or embellished, though the gown would usually have had muslin flounces at the neckline and sleeves. When worn as part of an ensemble, the wearer usually accessorized the gown with a silk sash at the waist and a large hat, which could be trimmed with any combination of flowers, feathers, or ribbons. A lightweight fichu (Fig. 3), made from fine linen or cotton, could be worn over the bosom (Cassin-Scott 85).

Marie Antoinette was not the first to wear this style, and nor was she the last. The Queen and her close friends, such as the Princesse de Lamballe, would don chemise dresses and straw hats when visiting the Hameau de la Reine, or Queen’s Hamlet, where they would “play at being country-folk” (Tortora). A portrait from 1782 shows the Princesse de Lamballe wearing a robe en chemise that looks similar to the one in Marie Antoinette’s 1783 portrait, which would have been appropriate for spending time at the Hameau de la Reine, a sort of faux peasant rustic retreat (Fig. 4). The sleeves are worn in the same puffed style, and the Princesse de Lamballe’s straw hat is trimmed with the same color ribbon and feather as Marie Antoinette’s. The main difference is that the Princess wears a blue-gray ribbon around her waist, as well as at the center of her low neckline.

By 1788, dress was fashionable outside of court as well, as demonstrated by Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze posing for a portrait with her husband (Fig. 5). David’s portrait of Paulze shows the whole robe en chemise, which Paulze wears with a blue sash and corresponding blue ribbons to keep her sleeves just at the elbow. The skirt of Paulze’s gown appears to be slightly more shaped than Marie Antoinette’s; it almost balloons outwards, and ends in a small train.

Though the robe en chemise appears relatively simple, particularly in comparison to previous fashions, numerous factors went into its creation and upkeep that were anything but simple. The muslin was imported from India, and creating the ruffles was fairly labor intensive. Once the fabric had been shipped and sewn into a garment, it had to be maintained, which required a significant amount of labor; the pristine white dress was a symbol of wealth (London).

The style soon spread outside of France. Marie Antoinette gifted some muslin to her friend, Georgiana of Devonshire (Weber 185). Georgiana brought the robe en chemise into the public eye in England by wearing one to a concert in 1784 (National Trust). A close friend of hers, Lady Elizabeth Foster, was painted by Angelica Kauffman wearing a robe en chemise in 1786 (Fig. 6). Foster wears the requisite large straw hat, but the sash is thinner than worn in France, and her sleeves are relatively tight to the wrist. A 1787 portrait by George Romney, Mrs. Billington as Saint Cecilia, also shows an example of the robe en chemise, this one with puffed sleeves and a wide pink sash (Fig. 7). Mrs. Billington wears a veil instead of a hat, and her hair is un-powdered, but this is likely intended to reference Saint Cecilia.

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (French). Fichu, ca. 1789. Cotton. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.57.69. Gift of Miss Lydia St. Clair, 1957. Source: The Met

Fig. 4 - Élisabeth Vigée Le brun (French, 1755-1842). Marie-Thérèse-Louise de Savoie-Carignan, princesse de Lamballe, 1782. Oil on canvas; 80.8 cm x 60.5 cm (31.8 in x 23.8 in). Versailles: Palace of Versailles, V2011.45. Bought November 2011. Source: Versailles

Fig. 5 - Jacques Louis David (French, 1748-1825). Antoine Laurent Lavoisier (1743–1794) and His Wife (Marie Anne Pierrette Paulze, 1758–1836), 1788. Oil on canvas; 259.7 x 194.6 cm (102 1/4 x 76 5/8 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1977.10. Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gift, in honor of Everett Fahy, 1977. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 6 - Angelica Kauffman (English, 1741-1807). Lady Elizabeth Christiana Hervey, Lady Elizabeth Foster, later Duchess of Devonshire (1759-1824), 1786. Oil on canvas; 127 x 101.6 cm (50 x 40 in). Ickworth: National Trust, NT 851738. Source: National Trust Collections

Fig. 7 - George Romney (English, 1734-1802). Mrs. Billington (1765/1768-1818) as Saint Cecilia, 1787-88. Oil on canvas; 127.7 x 101.9 cm (50 1/4 x 40 1/8 in). Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 23.397. Bequest of Mrs. David P. Kimball. Source: Museum of Fine Arts

Its Legacy

Vigée Le Brun enjoyed a lucrative career, but the political instability of the Revolution and her proximity to the aristocracy, particularly Marie Antoinette, invited slander from the press. She fled France in 1789 with her daughter and spent 1789-1802 traveling Europe and painting. She returned to France sporadically after 1802, and settled there again in 1805.

The chemise dress never quite went out of style during Vigée Le Brun’s exile. The silhouette gradually became narrower and the waist rose, but sheer muslin gowns tied with sashes became a staple of the 19th century. David’s 1799 portrait shows how the robe en chemise evolved (Fig. 8). It was a fashion that proved to outlast the Revolution and live on into the Napoleonic era.

Fig. 8 - Jacques Louis David (French, 1748-1825). Portrait of Madame de Verninac, 1799. Oil on canvas; 145.5 x 112 cm (57.2 x 44 in). Paris: Louvre, RF1942-16. Bequeathed by Carlos de Beistegui. Source: Louvre

References:

- Cassin-Scott, Jack. The Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Costume and Fashion: From 1066 to the Present. London: Cassell Illustrated, 2006.

- Château de Versailles. “Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun.” Accessed October 16, 2020. http://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/history/great-characters/elisabeth-louise-vigee-brun#official-artist-to-marie-antoinette

- “Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun | Marie Antoinette in a Chemise Dress.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed October 16, 2020. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/656930.

- Haroche-Bouzinac, Geneviève, Katharine Baetjer, Paul Lang, Ekaterina Deryabina, Gwenola Firmin, Stéphane Guégan, Anabelle Kienle Poňka, et al. Vigée Le Brun. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2016.

- Hennessey, Kathryn. DK, Publishing, Inc, and Institution Smithsonian. Fashion: The Definitive History of Costume and Style. Edited by Susan Brown. 1st American ed. New York, N.Y: DK Publishing, 2012.

- Kawamura, Yuniya. “Fashion Dominance in France: History and Institutions.” In The Japanese Revolution in Paris Fashion, 21-34. Ebook. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2004. Accessed October 22, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/9781847888907/JREVPARFASH0007

- “Lady Elizabeth Christiana Hervey, Lady Elizabeth Foster.” National Trust. Accessed October 16, 2020. http://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/851738

- London, Caroline. “The Marie Antoinette Dress That Ignited the Slave Trade.” Racked, January 10, 2018. https://www.racked.com/2018/1/10/16854076/marie-antoinette-dress-slave-trade-chemise-a-la-reine.

- Nicholson, Kathleen. 2003 “Vigée Le Brun [Vigée-Le Brun; Vigée-Lebrun], Elisabeth-Louise.” Grove Art Online.17 Dec. 2018. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000089458.

- Steele, Valerie. Paris Fashion: A Cultural History. London: Bloomsbury, 2017.

- Tortora, Phyllis G., and Sara B. Marcketti. Survey of Historic Costume. Sixth edition. New York, NY: Fairchild Books, 2015.

- Weber, Caroline. Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution. 1st ed. New York: H. Holt, 2006.

- “What Do You Wear under a Chemise a La Reine? 2.0.” The Dreamstress (blog), October 16, 2020. http://thedreamstress.com/2018/02/what-do-you-wear-under-a-chemise-a-la-reine-2-0/.