Textile lace made by braiding and twisting thread on a pillow.

The Details

Fairchild’s Dictionary of Textiles (1959) defines bobbin lace as:

“A handmade lace made on a pillow or cushion; the design is outlined on the pillow with pins and the thread is drawn and interlaced around the pins. Before the use of pins, fine fishbones were used, from which the term bone lace is derived. The thread is held on small bobbins. Synonym: pillow lace.” (Marks 61)

The Musée des Ursulines de Québec has bobbin lace in progress on display showing the characteristic pillow and dangling bobbins (Fig. 1). The Rijks Museum has a 16th-century drawing depicting the bobbin lace-making process (Fig. 2). Wikipedia describes the process in detail:

“Bobbin lace is a lace textile made by braiding and twisting lengths of thread, which are wound on bobbins to manage them. As the work progresses, the weaving is held in place with pins set in a lace pillow, the placement of the pins usually determined by a pattern or pricking pinned on the pillow. Bobbin lace is also known as pillow lace, because it was worked on a pillow, and bone lace, because early bobbins were made of bone or ivory. Bobbin lace is one of the two major categories of handmade laces, the other being needlelace, derived from earlier cutwork and reticella.”

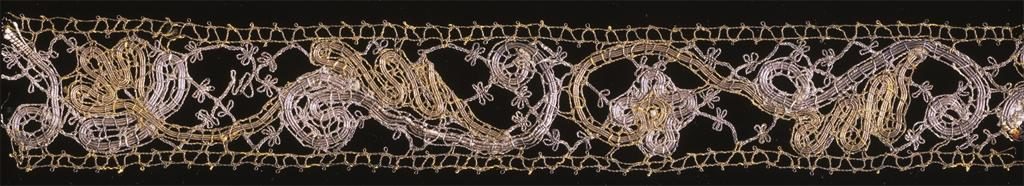

In Portrait of a Lady (Fig. 3), formerly identified as Christina of Denmark, the anonymous painter renders early bobbin lace in gold and silver thread. Figure 4 showcases Italian bobbin lace of gold and silver. Arts and Humanities Through the Eras describes the importance of lace to 17th-century Dutch dress and the hybrid origins of early lace-making techniques:

“Two of the most characteristic decorative items of the time were the ruff and lace. Lace, the product of an industry that had thrived in the Netherlands since the Middle Ages, was almost always confined in Dutch fashions to the wrists and neck. During the seventeenth century Dutch traders conducted a busy trade in lace, which was primarily woven by peasant and poor city women in the towns of Flanders in the southern Netherlands. In contrast to the strongly geometric patterns of the later Middle Ages and the sixteenth century, this Belgian lace became increasingly ornate after 1600, first incorporating floral patterns into its designs and then elaborate, running scrollwork patterns by the mid-seventeenth century. Somewhat later, small freestanding ornaments came to be inserted into the open weave of the fabric at regular intervals. The techniques used to produce these highly prized designs relied on a combination of methods that were both native to the region and which were imported from Italy. During the Middle Ages Belgian lacemakers had developed their art by weaving together threads from scores of bobbins assembled on a frame with hundreds of pins rising from its surface. The character of this work was fine, but angular in its orientation since the threads were woven around numerous pegs.”

In the 19th century, inexpensive machine-made laces largely displaced hand-made laces like bobbin lace, so the bobbin laces that were created tended to be of luxury materials (Fig. 5).

Fig. 1 - Unknown. Bobbin lace in progress at the Musée des Ursulines de Québec. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 2 - Anonymous artist. De kantwerkster, 1600-1620. Pen, brush on paper; 18.1 x 14.2 cm (7.12 × 5.6 in). Amsterdam: Rijks Museum, RP-T-1886-A-597. Source: Rijks Museum

Fig. 3 - Gillis Claeissens (Belgian, 1526-1605). Portrait of a Lady (formerly identified as Christina of Denmark), 1521-1590. Oil on panel; 34.29 x 25.4 cm (13.5 x 10 in). Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 4 - Maker unknown (Italian). Lace edging, 1450 - 1550. Italian bobbin lace of gold and silver wire and silk; 4.4 x 33.0 cm (1 3/4 x 13 in). Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1894-30-105. Gift of the Associate Committee of Women, 1894. Source: Philadelphia Museum of Art

Fig. 5 - Makers unknown (French). Edgings, late 1800s–early 1900s. Metallic gold bobbin lace. Berkeley: Lacis Museum of Lace and Textiles, JTB23789, L2013.3501.057, JTB23779, JTB23791, JTB23775, L2013.3501.057, 058, .059, .095. Source: FAMSF

Its Afterlife

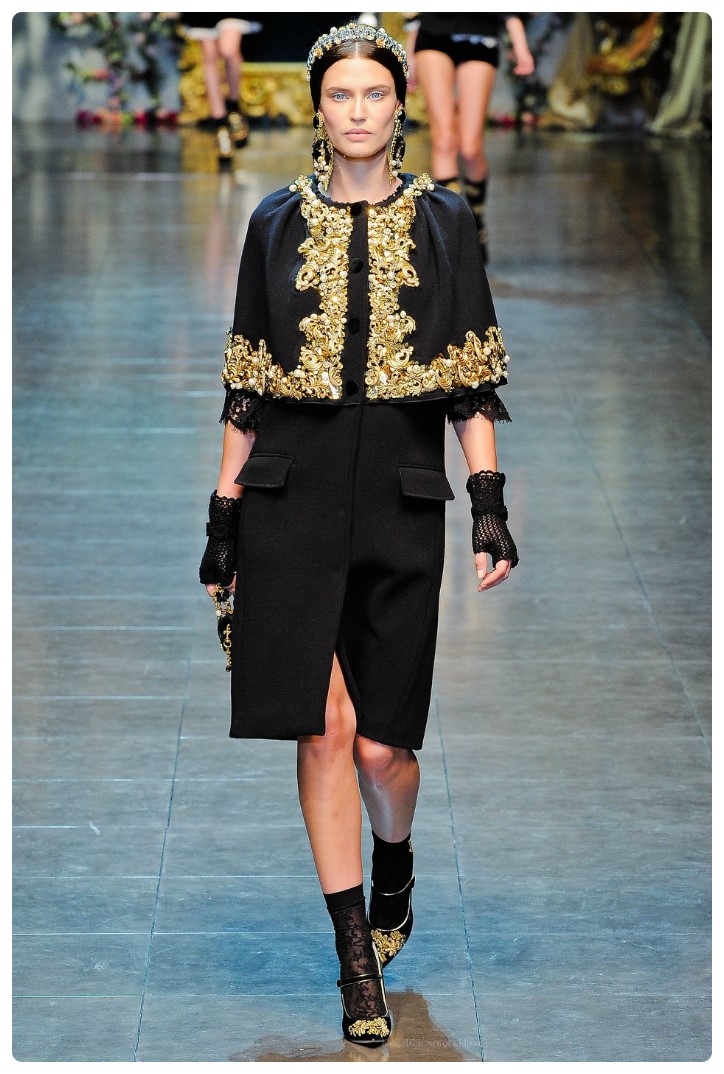

Bobbin lace’s intricate designs are still seen in fashion today. In this new age, the look of bobbin laces have changed with a twist by adding new ideas, colors, and techniques from its old style. Figures 6 and 7 feature looks by modern designers Marchesa and Dolce & Gabbana that are inspired by bobbin lace in their Fall and Winter collections.

Fig. 6 - Marchesa. Ready to Wear, Fall/Winter 2014. Photo: Umberto Fratini. Source: Vogue

Fig. 7 - Dolce & Gabbana. Ready-to-Wear, Fall 2012. Model: Bianca Balti. Photo: Yannis Vlamos. Source: Vogue

References:

- “Bobbin Lace.” Wikipedia, January 6, 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Bobbin_lace&oldid=818866446.

- “Looking at Lace.” FAMSF, June 9, 2014. https://www.famsf.org/blog/lace.

- Marks, Stephen S. Fairchild’s Dictionary of Textiles. New York: Fairchild Publications, 1959. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/636732446.

- “The Rise of the Netherlands.” In Arts and Humanities Through the Eras, edited by Edward I. Bleiberg, James Allan Evans, Kristen Mossler Figg, Philip M. Soergel, and John Block Friedman, 117-119. Vol. 5, The Age of the Baroque and Enlightenment 1600-1800. Detroit: Gale, 2005. Gale Virtual Reference Library (accessed January 6, 2018). http://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2540/apps/doc/CX3427400836/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=13132430.