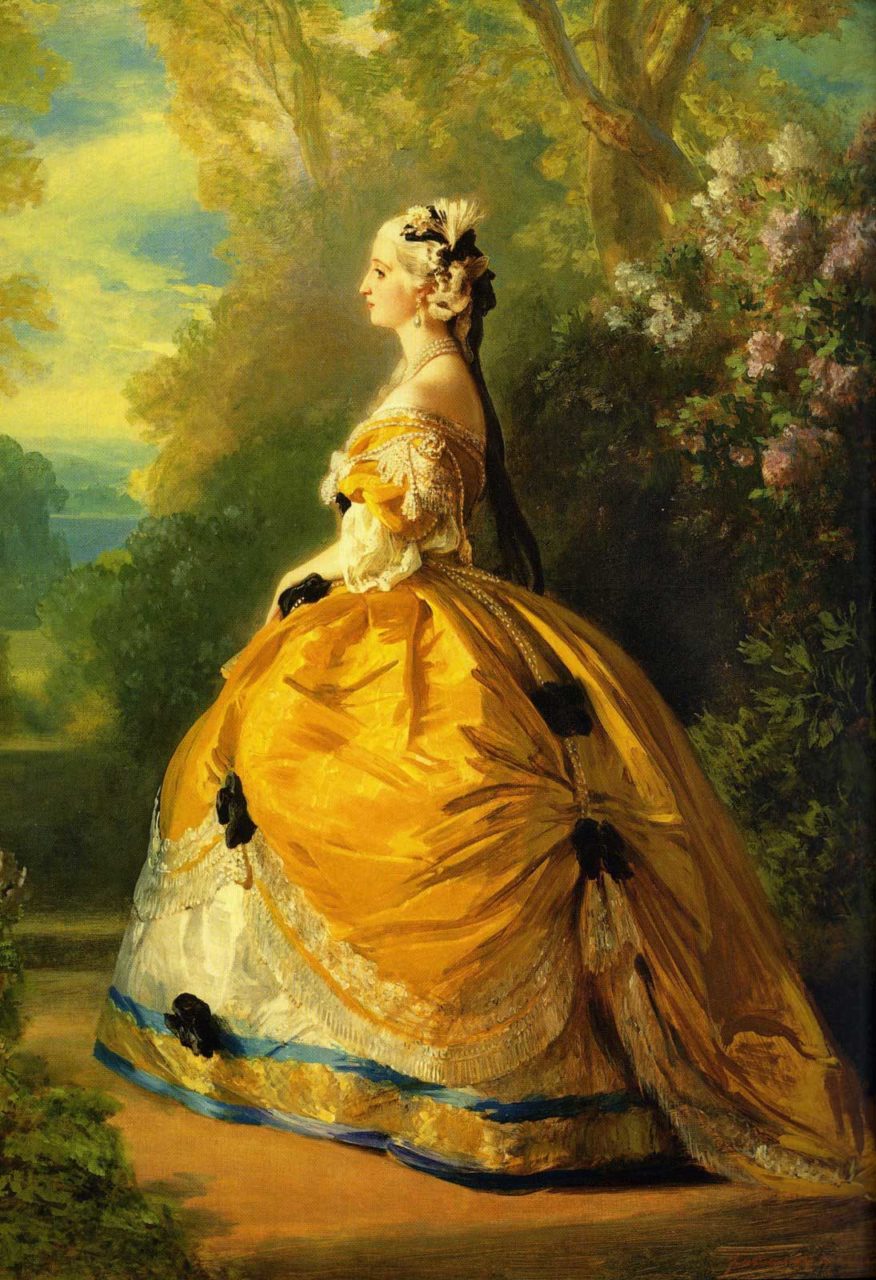

Well-known in the 19th century for his skill at portraiture, Wintherhalter created iconic mannered poses and captured ravishingly elegant dresses, like those in this portrait of the Empress Eugénie and her ladies in waiting, who dress in the most fashionable styles of day.

About the Portrait

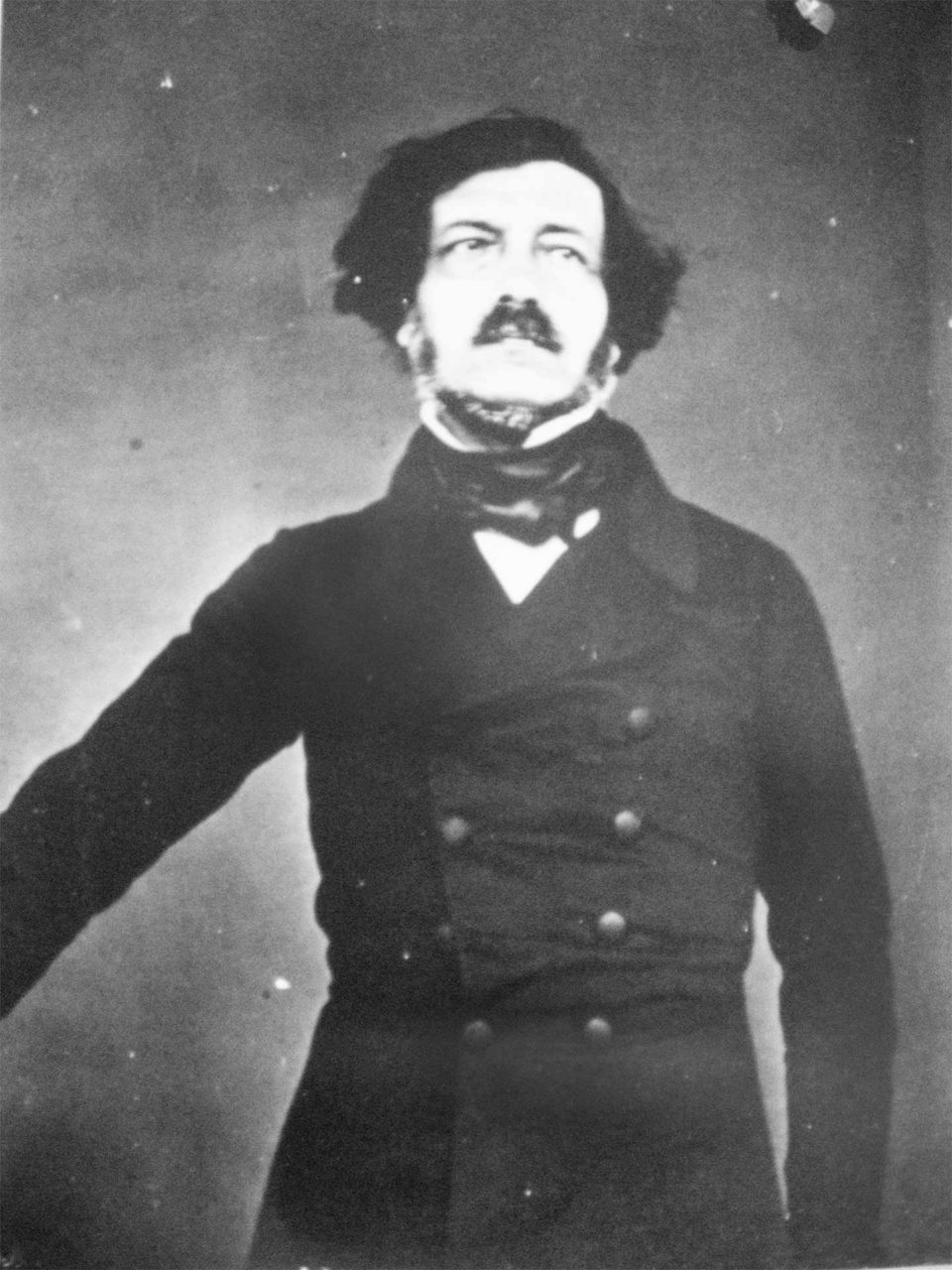

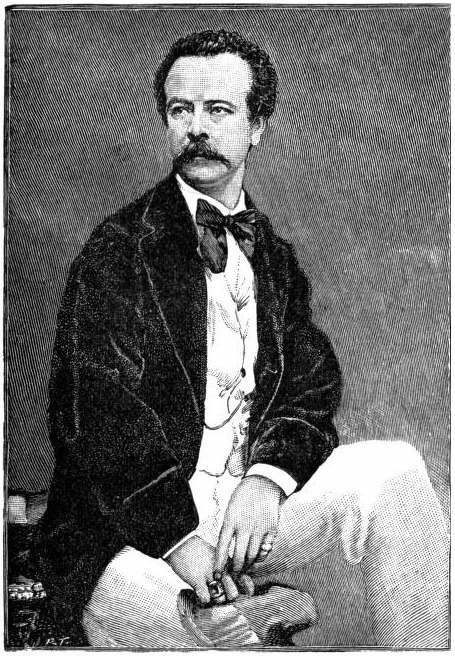

Franz-Xaver Winterhalter (Fig. 1) is well-known for his fashionable portraiture of the 19th century. Born in Germany in 1805, he became the portraitist for the royal courts of Europe. In France he was the favorite painter of the Empress Eugénie during the Second Empire (Grove).

In 1825, he became assistant to Joseph Karl Stieler who was popular for his court portraiture. He greatly influenced Winterhalter’s style and was the inspiration for French neo-classical paintings. In 1834, he moved to Paris and served as court painter at Baden, exhibiting at the Salon for the first time in 1836. After a period of decreased demand in portraiture, he decided to explore a creative and fantastical subject matter by painting Florinda (Fig. 2) which he exhibited at the Great Exhibition in 1851 by the Royal Academy in London. The aesthetic beauty of the composition was so greatly admired by the public that Queen Victoria bought it for her husband. In spring of 1853, Winterhalter surpassed Empress Eugénie’s expectations after painting her first portrait of her, which greatly advanced the painter’s career due to the Empress’s fame and connections. In 1855, he painted the masterpiece The Empress Eugénie Surrounded by her Ladies-in-Waiting. Like Rubens had in the 17th century, Winterhalter developed extensive connections in the royal houses painting countless aristocratic portraits (Ormond 203).

Fig. 1 - Dr. Ernst Becker (British, 1826-1888). Mr F. Winterhalter (1805-73), 27 Jun 1854. Albumen print; 13.5 x 10.6 cm. London: Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 2906113. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 2 - Franz-Xaver Winterhalter (German, 1805-1873). Florinda, 1853. Oil on canvas; 178.4 x 245.7 cm. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 01.21. Bequest of William H. Webb, 1899. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

The sitter

The Empress Eugénie (Fig. 3) was born Eugenia de Montijo in Spain in 1826. She met Louis Napoleon when he was president of the Second Republic in 1849, and four years later they married at the Tuileries. She used arts to create a positive image of the Second Empire and became an important collector and patron in the same way as Queen Victoria had (McQueen).

She was so mesmerized by Marie Antoinette that one of the first paintings commissioned to Winterhalter (Fig. 4) depicted a Rococo Revival style, using as reference a photograph of the Empress dressing as the late monarch (Fig. 5). A similar influence was displayed in her next portrait, where she wanted to convey a humble image, letting her ladies-in-waiting wear jewelry while wearing none herself, even though she was an important collector of jewelry. She holds a honeysuckle branch, which was the symbol of her crown worn during the exhibition of the masterpiece (Merle).

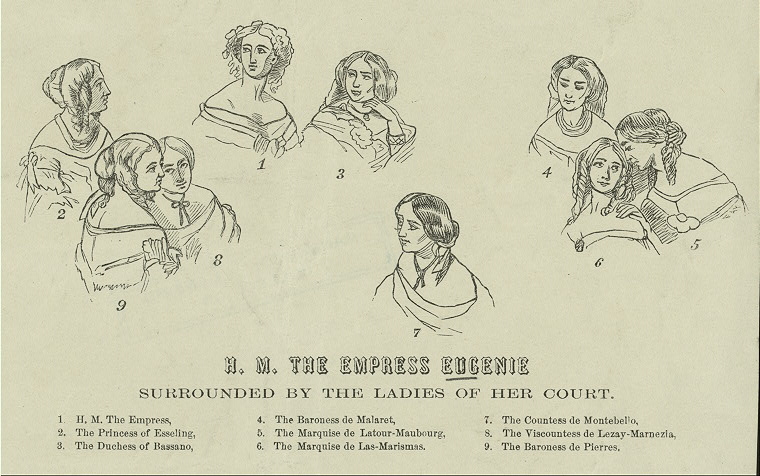

This painting was the evolution of Winterhalter’s Florinda, using the same arrangement in the composition and recreating a similar pastoral scene in which the influence of Watteau revives a utopian vibe. The preparatory sketch reveals the presence of another lady who left the royal service later and was not represented in the final work (Fig. 6). In January of 1855, the number of dames du palais was raised to thirteen by decree, which emphasized the honored position of the ones included in the final painting (Fig. 7) (Ormond 203).

Fig. 3 - Gustave Le Gray (French, 1820-1884). L'impératrice Eugénie en prière, 1856. Albumen silver print from a collodion glass negative; 23.4 x 18.3 cm (9 3/16 x 7 3/16 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum o Art, 2005.100.258. Gilman Collection, Purchase, Harriette and Noel Levine Gift, 2005. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 4 - Franz-Xaver Winterhalter (German, 1805-1873). The Empress Eugénie (Eugénie de Montijo, 1826–1920, Condesa de Teba), 1854. Oil on canvas; 92.7 x 73.7 cm (36 1/2 x 29 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1978.403. Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Claus von Bülow Gift, 1978. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 5 - Franz-Xaver Winterhalter (German, 1805-1873). Empress Eugénie à la Marie Antoinette, 1854. Photograph. Private Collection. Source: Pinterest

The reception

The large portrait was exhibited in a special room at the Exposition Universelle of 1855, where Winterhalter won a first-class medal for his work. The success of the painting was perhaps in part due to the censorship imposed by Napoleon III; nevertheless, Winterhalter received several critical reviews including one by G. Planche in La Revue des Deux Mondes:

“simply a parody of Watteau, but a parody whose proportions do not allow indulgence.”

The portrait was on view in the Fontainebleau palace during the Second Empire (Ormond 203).

Fig. 6 - Franz-Xaver Winterhalter (German, 1805-1873). Empress Eugénie and Her Ladies-in-Waiting (oil sketch), 1855. Oil on canvas; 35.5 x 40 cm (13.98 x 15.75 in). Donaueschingen: Fürstlich Fürstenbergische Sammlungen. Source: The Athenaeum

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown. H.M. Empress Eugenie, ca. 1855. Ink on paper. New York: New York Public Library. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs. Source: New York Public Library

Franz-Xavier Winterhalter (German, 1805-1873). Empress Eugénie , Surrounded by Her Ladies-in-Waiting, 1855. Oil on canvas; 402 x 300 cm. Compiègne: Musée National du Château de Compiègne. Source: Wikimedia Commons

About the Fashion

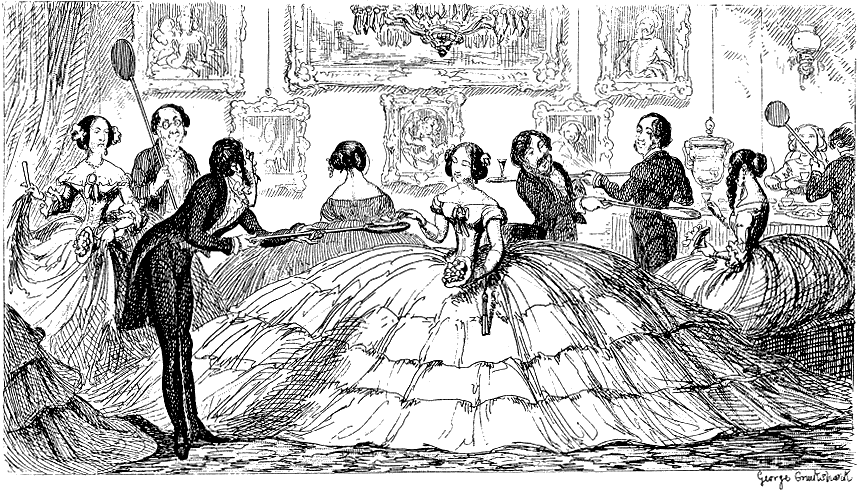

Empress Eugénie was a trendsetter during the Second Empire and the portrait displays her luxurious style. The flounced skirts of that period were artificially expanded through the use of a lighter and more flexible crinoline, a new technology that allowed the widest silhouette of that century. The crinoline revived Marie Antoinette’s opulence and lavish style, enabling the press to satirize the voluminous dresses (Fig. 8) (Tortora 303).

The Empress wears a ball-dress of white silk overlaid with white tulle. The stripes and loops are formed by lilac silk and ribbon trimmings, with a wide bow on the front of the bodice. All the women’s dresses feature off-the-shoulder necklines, which were popular for evening wear and often associated with Winterhalter paintings. One dame du palais has a skirt trimmed with blue bow ribbons and two others wear a crisp textured taffeta in green and pink (Stevesons 52).

Some of the dames—including the Empress—have attached lace berthas at the top of the décolleté bodice, which covers the bust; others wore bretelles with ribbons instead. These oversized proportions are accentuated by the black tulle shawl worn by the Grande-Maîtresse, who is next to the Empress. Two dames du palais wear black ribbon bow choker necklaces. In the right side, one dame du palais carries a leghorn straw hat trimmed with roses and white tulle, similar to those during the Rococo era (Ormond 203).

Fig. 8 - George Cruikshank (British, 1792-1878). "A Splendid Spread" from The Comic Almanack, 1849. Source: Wikipedia

Diagram of referenced dress features.

Source: Author

Fig. 9 - Artist unknown. Toilettes d'été, Journal des Jeunes Personnes, July 1855. Hand-colored engraving; (6.625 x 10.375 in). Claremont: Ella Strong Denison Library. Macpherson Collection, Costume Plates of Myrtle Tyrrell Kirby, box 8. Source: Scripps College

Fig. 10 - Compte Calix (French, 1813-1880). Les Modes Parisiennes, vol. 37 (December 1855): plate 114. Hand-colored engraving. Los Angeles: Casey Fashion Plates, rbc4426. Source: LAPL

Fig. 11 - Designer unknown (American or French). Ball dress, about 1858. Silk plain weave (taffeta), machine net (tulle) and silk bobbin lace; trimmed with silk ribbon, embroidered silk net, and silk flowers; 34.9 x 52.7 cm (13.75 x 20.75 in). Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 51.1346a-b. Gift of Ronald T. Lyman. Source: MFA

Similar design features can be found in contemporary fashion plates and surviving dresses. A July 1855 fashion plate from the Journal des Jeunes Personnes features a tiered white satin dress with a lace bertha and pink floral accents almost identical to the seated woman at right (Fig. 9). The bright pink gown at the far left of the portrait finds its echo in both a December 1855 fashion plate (Fig. 10) and a surviving ball gown from a few years later (Fig. 11).

It is likely that Charles Frederick Worth, the father of haute couture, created the sitter’s gown (Fig. 12). He was known for his collaborations with other artists, including with Winterhalter. The Empress never wore a dress twice, and two times a year, she changed her entire closet. The discarded gowns were part of the payment for the dames du palais, which they often sold later to Americans (de Marly 42).

Worth was a designer who made popular the collection system, and the concept of the couturier as an artist by using designer labels for the first time. His business was established in the 1850s. As a result, the Empress Eugénie’s relationship with Worth was influential in his career, helping him to propel his brand (Cunnington 205).

Fig. 12 - Photographer unknown. Engraved portrait of Charles Frederick Worth, fashion designer, aged 30, 1855. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The setting & context

During the Second Empire (1852- 1870), France became a capital for consumerism. The city was being reconstructed with wide boulevards and beautiful parks. Winterhalter was one of the painters that captured the opulence of the imperial lifestyle, giving him great recognition during Napoleon III’s reign. This painting depicts court life, where the Empress shows her interest in fashion while she sits surrounded by her dames du palais with a Rococo revival countryside setting. Her impact on fashion was shown in an English magazine that wrote:

“The Empress Eugénie[‘s] petticoats… stood out a great deal: and following her example, all the Paris ladies are wearing their skirts very wide and ample.”

As a matter of fact, the lilac color of the Empress has major significance due to the expensive price of natural purple dye at that time. Soon after, a synthetic dye arrived in France and increased the demand in America and Europe for the Empress’s chosen color (Brown 195).

Fig. 13 - Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (French, 1780–1867). Joséphine-Éléonore-Marie-Pauline de Galard de Brassac de Béarn (1825–1860), Princesse de Broglie, 1851-53. Oil on canvas; 121.3 x 90.8 cm (7 3/4 x 35 3/4 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975.1.186. Robert Lehman Collection, 1975. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 14 - Isidore Pils (French, 1813/5-1875). Empress Charlotte of Mexico, 1859. Oil on canvas. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 15 - Franz-Xaver Winterhalter (German, 1805-1873). The Empress Elisabeth of Austria, 1865. Oil on canvas; 255 x 133 cm. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum. Source: WikiArt

The ideal

In France, the new, young and slender Empress quickly became a fashion leader. Besides her beauty, she had the advantage of having Charles Frederick Worth and his designs at her disposal.

Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres, another important portraitist in that moment, painted his portrait of the Princesse de Broglie (Fig. 13) in 1851-53, which features a gown similar to those worn by the dames du palais with an off-the-shoulder neckline, tiers of lace sleeves, and ample skirt. Isidore Pils painted Empress Charlotte of Mexico in another similar gown a few years later (Fig. 14). Even a decade later, Winterhalter’s portrait of Empress Elisabeth of Austria (Fig. 15) still features the layers of satin and tulle similar to Empress Eugénie’s white gown and a tulle shawl like that worn by the Grande-Maîtresse that created a cloud-like texture (Brown 125).

Its Legacy

F

ranz-Xaver Winterhalter’s canvases left a broad catalog of images that are capable of narrating a period in fashion when couture was born. The well-rendered textures in the paintings depict in great detail Worth’s couture garments. During that period, the Empress Eugénie was the most important patron for the developing of fashion, inspiring and connecting the two artists to a wider audience. Her fashion choices were greatly copied, and some clothes even bore her name—such as the Eugénie petticoat that was first advertised in December 1854. Besides the 19th-century trends she inspired, the Empress Eugénie also was the muse of Nicolas Ghesquière, creative director of Louis Vuitton (Fig. 15). A 2013 exhibition about her influence in fashion, Timeless Muses, wrote of Eugénie’s influence on Worth:

“Her aura, influence and passion for travel fueled his worldwide fame and she became the house’s first and devoted ambassadress.” (Lange)

Fig. 15 - Louis Vuitton. "Timeless Muses", 2013. Source: Louis Vuitton

References:

- Brown, Susan, ed. Fashion: The Definitive History of Costume and Style. New York: DK Publishing, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/840417029.

- Cunnington, C. Willett. English Women’s Clothing in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Dover Publications, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/868281120.

- De Marly, Diana. Worth: Father of Haute Couture. London: Elm Tree Books, 1980. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/955329175.

- Hill, Daniel Delis. History of World Costume and Fashion. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/768100950.

- McQueen, Alison. Empress Eugénie and the Arts: Politics and Visual Culture in the Nineteenth Century. Farnham, Surrey, England: Ashgate, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/756281477.

- Lange, Barbara. “Winterhalter, Franz Xaver.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed November 19, 2016. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T091866

-

Merle, Sandrine. “Eugénie, impératrice du bijou.” The French Jewelry Post. Accessed October 19, 2018. https://www.thefrenchjewelrypost.com/style/eugenie-imperatrice-bijou/.

- Stevenson, N. J. Fashion: A Visual History from Regency & Romance to Retro & Revolution. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/740627215.

- Ormond, Richard, Carol Blackett-Ord. Franz Xaver Winterhalter and the Courts of Europe, 1830-70. London: National Portrait Gallery, 1992. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/317672454.

- 100 Dresses: The Costume Institute, the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/739.

- Tortora, Phyllis G. “Iconic Figures in Western Fashion.” in Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: Global Perspectives, edited by Joanne B. Eicher and Phyllis G. Tortora, 171–174. Oxford: Berg, 2010. Accessed November 15, 2016. <http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/BEWDF/EDch10021

- Vuitton, Louis. “News By Louis Vuitton: ‘Timeless Muses’ Opens at the Tokyo Station Hotel.” LOUIS VUITTON. Accessed November 15, 2016. http://us.louisvuitton.com/eng-us/articles/timeless-muses-opens-at-the-tokyo-station-hotel