OVERVIEW

In 1856, women’s dresses were made mostly in silk, cotton, and velvet, and their silhouettes consisted of bodices fitted to the waist and full bell skirts that were accessorized with flounces, stripes, trims, and flowers.

Womenswear

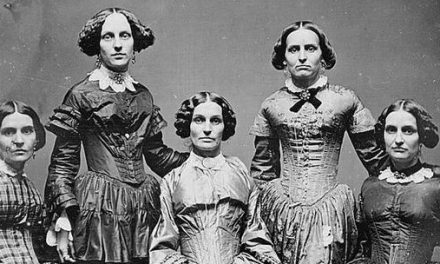

As a new year began in 1856, dress silhouettes were almost universal: dresses had full bell skirts, often with tiered flounces, and bodices remained fitted to the waist. However, new trends emerged, and at the start of 1856, one of the prevailing fabrics seen in public was velvet. Women’s designs utilized velvet in full fabric on the notorious bell skirts (Fig. 1), or as details on other materials like silk and taffeta. As a detail, velvet was used as an embroidery in a floral or geometric shape, or in broad stripes. Described in the January issue of The London and Paris Ladies’ Magazine of Fashion, stripes of velvet subtly increased a dress’ elegance in a way that was not commonly seen in previous years (Chere 11), (Fig. 2). Often, a dress’s velvet stripes were edged with a narrow black lace, adding a luxurious and unique detail to evening wear (Jones 96) (Fig. 3).

In addition to seeing stripes of velvet in evening wear, striped patterns rose in popularity in day wear as well. Emily H. May in Peterson’s Magazine (January 1856) states:

“The new patterns in almost every material introduced for autumn and winter out-door dresses, consist mostly of stripes or chequers, and much variety is obtained by the tasteful arrangement of colors…some of the most beautiful of the new silks have broad, perpendicular stripes.” (101)

Though used in different varieties and areas of dress, vertical stripes were seen in fashion plates throughout the entire year (Fig. 4). Often used as the entire gown’s fabric, stripes added an interesting aspect to women’s fashion. Stripes were created in different colors and widths, but remained in prevalence all the same for women of different ages and classes (Fig. 5). In addition to striped fabric, evening and day dresses were also embroidered with stripes of fringe, tassels, or lace. These dress ornaments were seen mostly on 1856 bell skirts, but they often also adorned the neckline and sleeves of particularly striking gowns, as seen in the fringe tassel embellished dress in figure 6 (Chere 50).

Fig. 1 - S. Montout. Les Modes Parisiennes, vol. 38, no. 17 (February 1, 1856). Source: Los Angeles Public Library

Fig. 2 - S. Montout. Les Modes Parisiennes, vol. 38, no. 33 (April 1, 1856). Source: Los Angeles Public Library

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown. Godey's Lady Book and Magazine, vol. 52, (February 1856). Source: Vintage Victorian

Fig. 4 - Hélöise Leloir (French, 1827-1878). Le Bon Ton, vol. 38, no. 76 (October 1, 1856). Source: Los Angeles Public Library

Fig. 5 - H. Aldr... (American). Young Woman in Striped dress, July 1856. Photograph. Norfolk, Virginia: Chrysler Museum of Art. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown. Dress, 1856. Silk plain weave ( taffeta), trimmed with silk fringe tassels, machine embroidered net, and bobbin lace. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 50.474a-b. Gift of Mrs. Harriet Ropes Cabot and Edward Jackson Lowell Ropes, 1950. Source: Museum of Fine Arts Boston

A side from stripes, another popular pattern for day wear in 1856 was plaid. Mr. G. Spencer Jones, hon. secretary of the Cosmopolitan Art Union, writes in Godey’s Lady Book and Magazine (January 1856):

“Tartan (plaids of high colors) is very much worn in street-dress. Queen Victoria probably set the fashion by appearing in a dress of Stuart tartan on her autumn visit to Paris. It has a very comfortable effect in the cold months. Tartan poplins are also fashionable.” (94)

Seen in figure 7 is a plaid printed dress in a neutral color, that also contains a subtle floral pattern. The silhouette is a classic for 1856, consisting of a bell skirt with flounces, with the flounces edged with ruffles and sleeves edged with fringe tassels. In figure 8, an elderly woman also wears a plaid dress, paired with a lace collar and cuff. Both plaid dresses, though varied, were probably stylishly seen on the streets of Paris in 1856.

For a more feminine look, 1856 was filled with laces and flowers. In the “general remarks” section of Peterson’s Magazine in May 1956, Ann S. Stephens notes:

“For elegant dresses suitable for a watering place, or evening wear, the corsages are made low in the neck, with a point before and behind. Sleeves are very short. Berthas are in favor. Thin skirts are plaited in large double plaits at the waist, with the under-dress to make them more voluminous.” (405)

The bertha, a deep collar typically made of lace and attached to the top of a low neckline dress, is seen in many different varieties in fashion plates throughout the year (Fig. 9). Being so fashionable, a bertha was also seen in a black lace in a portrait of Saturnina Canaleta de Girona, painted by Federico de Mandrazo y Kuntz (Fig. 10), as well as in a white lace in a photograph of Princess Victoria on her 16th birthday (Fig. 11). A corsage detail, (flowers pinned to a woman’s dress), is seen in the dress in figure 12, which also has a deep neckline with lace flounces. However, if not as corsages, flowers were still very present in printed fabrics. These colorful floral prints would be combined with striped fabrics (Fig. 13), or paired with a neckline corsage itself (Fig. 14).

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown (British). Plaid Ensemble, 1856. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985.20.3a–d. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn and Alice L. Crowley Bequests,. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 8 - William Hardy Kent (American, 1819–1907). Seated Elderly Woman Wearing Plaid dress and Bonnet, 1856. Photograph, daguerreotype with applied color; 9.2 x 6.4 cm (3 5/8 x 2 1/2 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015.400.28. Bequest of Herbert Mitchell, 2008. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 9 - Artist unknown. Les Modes Parisiennes, vol. 38, no. 16 (February 1856). Source: Los Angeles Public Library

Fig. 12 - Louis Bolior. Le Bon Ton, vol. 38, no. 14 (February 1, 1856). Source: Los Angeles Public Library

Fig. 10 - Federico de Madrazo y Kuntz (Spanish, 1815-1894). Saturnina Canaleta de Girona, 1856. Oil on canvas; 123 x 90 cm (48.24 x 35.43 in). Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado. Provenance of Legacy of Manuel Girona Canaleta II Count of Eletea, 1941. Source: Museo del Prado

Fig. 13 - Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (French, 1780-1867). Portrait of Madame Moitessier Sitting, 1856. Oil on canvas; 120 x 92.1 cm (47 x 36 1/4 in). London: National Gallery. Source: Art Renewal Center

Fig. 11 - Thomas Richard Williams (British, 1824-1871). Victoria Princess Royal on her Sixteenth Birthday, November 21, 1856. Photograph, salted paper print; 11.8 x 9.7 cm. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 14 - Designer unknown. Floral Evening dress, 1856. Silk. Kyoto: Kyoto Costume Institute. Source: Pinterest

P ortraiture is another source of information on 1856 fashions. Portrait of a Lady by Joseph Hussenot in 1856 (Fig. 15) depicts a fashionable woman in the year 1856, wearing a full, bell skirted dress with a low neckline and completed with a bertha. White lace lines the bertha as well as the ruffled skirt. Similar low-neckline looks in 1856 fashion plates are also paired with lace berthas (Figs. 9-11). Below the ruffles on the skirt, there are subtle stripes of fabric, which was as well one of the most prominent trends of the year. Lastly, the look is finished off with three corsages of red flowers, one on the neckline and two on the skirt. Most equivalently, a complimentary red corsage is seen on a February 1856 fashion plate (Fig. 12). As Ann S. Stephens stated in Peterson’s Magazine, corsages were suitable for “elegant dresses” (405). Altogether, making for a very fashionable lady in the year 1856.

Fig. 15 - Joseph Hussenot (French, 1827-1896). Portrait of a Lady, 1856. Oil on canvas; 157 x 103 cm (61.8 x 40.6 in). Source: Artnet

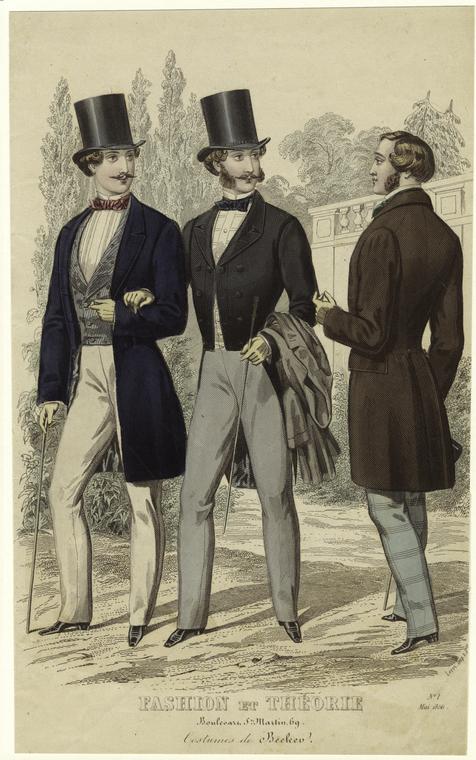

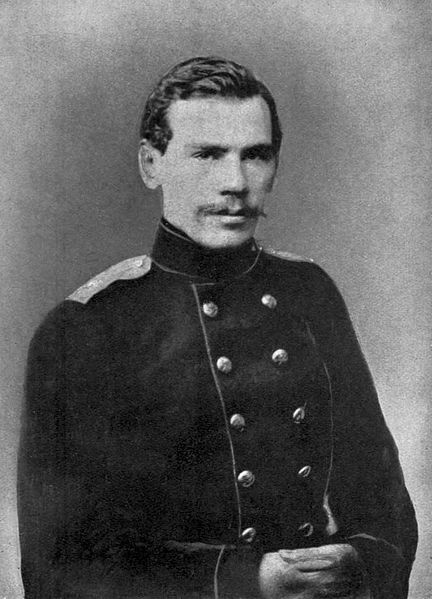

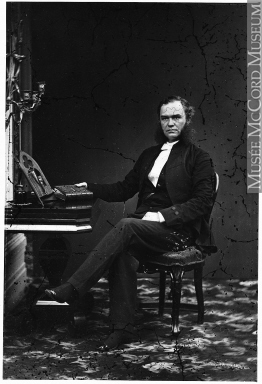

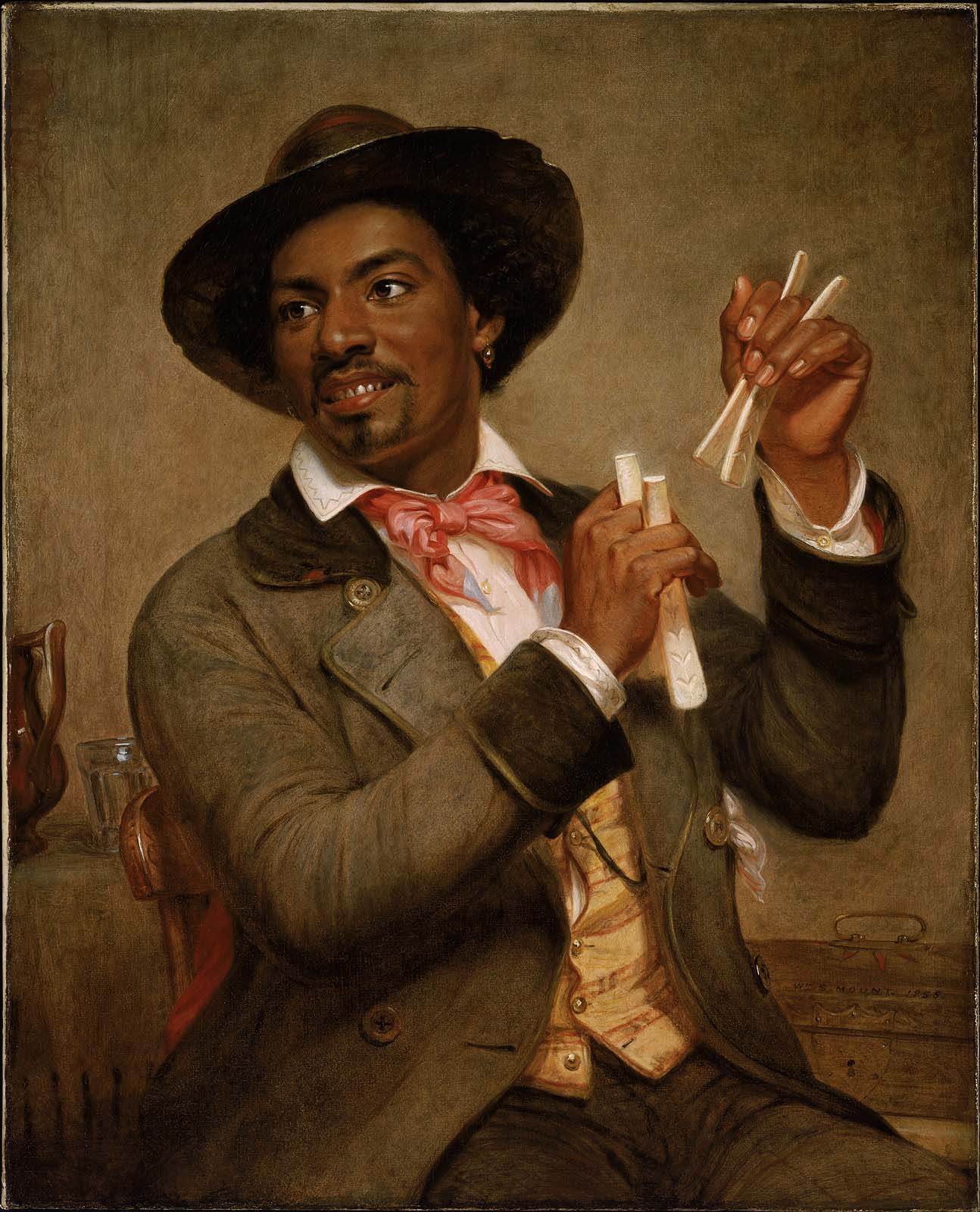

Menswear

[To come…]

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown. Fashion Et Théorie, no. 1, May 1856. Source: New York Public Library

Fig. 2 - Sergey Lvovich Levitsky (Russian, 1819-1898). Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, 1856. Photograph. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 3 - William Notman (Scottish-Canadian, 1826-1891). John Joseph Caldwell Abbott, Montreal, QC, 1856. Photograph; 10.4 x 8 cm. Quebec: Musée McCord. Source: Musee McCord

Fig. 4 - Federico de Madrazo y Kuntz (Spanish, 1815–1894). Jaime Girona y Agrafel, 1856. Oil on canvas; 123 x 90 cm (15.6 x 10.8 in). Madrid: Museo del Prado. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 5 - William Sidney Mount (American, 1807-1868). The Bone Player, 1856. Oil on canvas; 91.76 x 73.98 cm (36 1/8 x 29 1/8 in). Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 48.461. Source: Museum of Fine Arts Boston

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown. Le Bon Ton, vol. 38, no. 2, January 1856. Source: Los Angeles Public Library

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown. Les Modes Parisiennes, vol. 38, no. 8. January 1856. Source: Los Angeles Public Library

Fig. 3 - Marston Balt (American). Baltimore Sister and Brother, June 4th, 1856. Photograph. Source: Flickr

Fig. 4 - Augustus Henry Fox (English, 1822-1895). Boy and Girl in Landscape, 1856. Oil on canvas; 76 x 64 cm. Colchester and Ipswich: Colchester and Ipswich Museum, R.1951-3. Source: Art UK

Fig. 5 - Designer unknown. Girl's Silk dress, 1856. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979.346.74a–c. Gift of The New York Historical Society, 1979. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

References:

- Chere, Aimee. “Description of the Engravings.” London and Paris Ladies’ Magazine of Fashion 29, no. 301 (January 1856): 11–14, 50–53. https://books.google.com/books?id=1ScGAAAAQAAJ&q=fashions+for#v=onepage&q=fashions%20for&f=false

- Jones, G. Spencer. “Description of the Steel Fashion-Plate for January.” Godey’s Lady Book and Magazine 52 (January 1856): 93–96. https://books.google.com/books?id=R8dMAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- May, Emily H. “Fashions for January.” Peterson’s Magazine 29 (January 1856): 101–3. https://books.google.com/books?id=fptHAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Stephens, Ann S. “Fashions for May.” Peterson’s Magazine 29 (May 1856): 405–9. https://books.google.com/books?id=fptHAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1856

Rulers:

- England:

- Queen Victoria (1837-1901)

- France:

- Napoleon III (1852-1870)

- Spain:

- Queen Isabella II (1833-1868)

- United States:

- Franklin Pierce (1853-1857)

Map of Europe in 1856, End of the Crimean War. Source: Omniatlas

Events:

- March 30th 1856: The Treaty of Paris ends the Crimean War between the Russian Empire and the alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the British Empire, the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Sardinia. Signed at the Congress of Paris, the treaty made the Black Sea a neutral territory, prohibiting warships and fortification on its shores.

- Spring 1856: William Henry Perkin discovers the first synthetic organic dye, mauveine, made from aniline.

- November 1st 1856: The Anglo-Persian War beings between Great Britian and Persia, caused by British opposition to Persia’s attempt to take over the city of Herat, Iran.

- December 2nd, 1856: The National Portrait Gallery opens in London, housing a collection of portraits of historically important British people. When it opened, it was the first portrait gallery in the world.

- December 8th, 1856: Édouard Manet opens his own art studio.

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Fashion Plate Collections (Digitized)

- Costume Institute Fashion Plate collection

- Casey Fashion Plates (LA Public Library) - search for the year that interests you

- New York Public Library:

NYC-Area Special Collections of Fashion Periodicals/Plates

- FIT Special Collections (to make an appointment, click here)

- Journal des demoiselles (vol. 19-60, 1851-1892, with gaps) – AP20.J76

- Costume Institute/Watson Library @ the Met (register here)

- New York Public Library

- Brooklyn Museum Library (email for access)

Fashion Periodicals (Digitized)

Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Secondary Sources

Also see the 19th-century overview page for more research sources... or browse our Zotero library.