In Ingres’s 1856 portrait, Madame Moitessier wears a fashionable off-the-shoulder dress with a bertha collar trimmed with tassels. The evening dress reflects her elegant taste and features the essential elements of 1850s fashion–from its floral silk brocade fabric to its Renaissance-revival jewelry.

About the Portrait

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, born in 1780, was a towering figure of Neoclassicism in France. Steeped in the academic tradition as a pupil of Jacques-Louis David, Ingres became a defender of classicist style, which opposed the early nineteenth-century Romanticism in France (Shelton).

Ingres unswervingly pursued historical subjects throughout his career; however, he also enjoyed success as a portrait painter at the Paris Salon. His flattering, life-like portraits continuously attracted wealthy and powerful clients.

The sitter of this portrait, known as Madame Sigisbert Moitessier, was Marie Clotilde-Inès de Foucauld, the daughter of Charles-Édouard-Armand de Foucauld (1784-1849), who was a member of the ministry of state and the colleague of Charles Marcotte, a good friend of Ingres. The commission of her portrait was proposed in 1844 by Marcotte after Ingres’s return to Paris. As the demands of portraiture robbed him of time he could have spent painting historical subjects, Ingres initially refused the commission. Yet, later when he saw Madame Moitessier, he was moved by her beauty and changed his mind (Rabinow 426).

The painting took twelve years to complete and was finished in 1856. Its long gestation encompassed the death of Ingres’s wife, the death of Madame Moitessier’s father, and Moitessier’s second pregnancy. Significant revisions were made as time elapsed; for example, the composition once included her daughter Catherine, but she was removed. Madame Moitessier’s original yellow dress of the late 1840s was replaced with the fashionable flower-patterned chintz (Rabinow 440).

While at work on this seated portrait, Ingres started another standing portrait for her in 1851, which depicted her wearing an admirable black Chantilly lace gown standing against a violet damask background (Fig. 1).

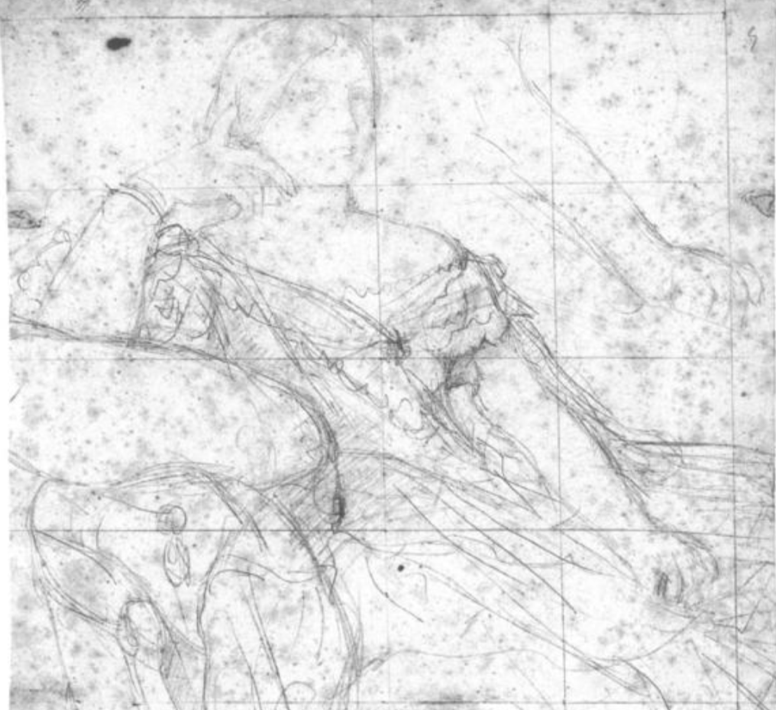

Preliminary studies for the seated portrait reveal Ingres’s careful attention the sitter’s dress and pose. He made substantial sketches particularly for her dress (Figs. 2-3), including of an alternate lace bertha collar.

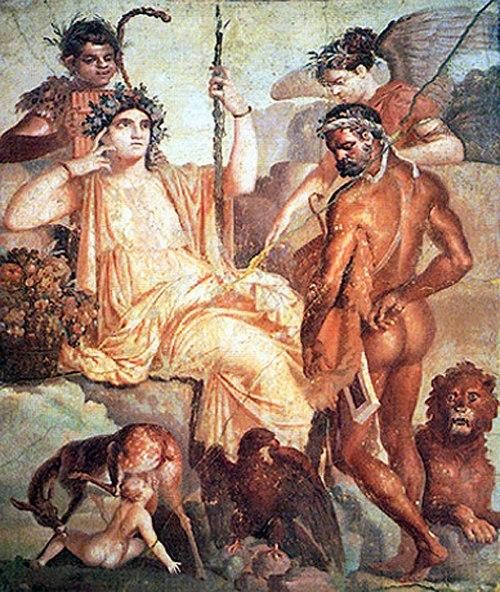

Meanwhile, her pose underwent little change, remaining the same from the beginning, especially in “the strangely unnatural hand with fingers arrayed like the arms of a starfish” (Rosenblum 164). Ingres is believed to have borrowed this remarkable gesture of seated Moitessier is believed from the famous ancient Roman wall painting Herakles Finding His Son Telephas (Fig. 4), which thus likens Moitessier to an Olympian goddess (Rabinow 429). By combining portraiture with a classical inspiration, the portrait of Madame Moitessier presented a possible resolution to Ingres’s antipathy of portraiture and his eager pursuit of historical paintings. He was able to embed touches of history painting, in particular classical forms and references, into contemporary portraiture.

Fig. 1 - Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (French, 1780-1867). Madame Moitessier, 1851. Oil on canvas; 147 x 100 cm (57 7/8 x 39 3/8 in). Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1946.7.18. Samuel H. Kress Collection. Source: National Gallery of Art

Fig. 2 - Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (French, 1780-1867). Study for Madame Moitessier, ca. 1846-48. Graphite on paper; 30 x 31.5 cm (11.8 x 12.4 in). Montauban: Musée Ingres. Source: Musée Ingres

Fig. 3 - Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Study for Madame Moitessier (Skirt), ca. 1847-48. Charcoal and white highlights on paper; 21.4 x 27.9 cm (8.4 x 10.9 in). Montauban: Musée Ingres. Source: Musée Ingres

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown. Herakles Finding His Son Telephas, 1st century AD. Roman fresco. Naples: Museo Nazionale. Source: Wikipedia

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (French, 1780–1867). Madame Moitessier, 1856. Oil on canvas; 120 x 92.1 cm (47 x 36 in). London: National Gallery. Source: National Gallery

About the Fashion

The artist’s enamel-like technique gives extraordinary precision to and illuminates the materiality of dress and jewelry, a grandiloquent display of wealth and the conspicuous consumption during the opulent French Second Empire. Madame Moitessier’s costume embodies most of her grandeur in the painting. The textures of the fabrics are extremely well-rendered and her glorious parure of jewelry is depicted with the jewel-like precision.

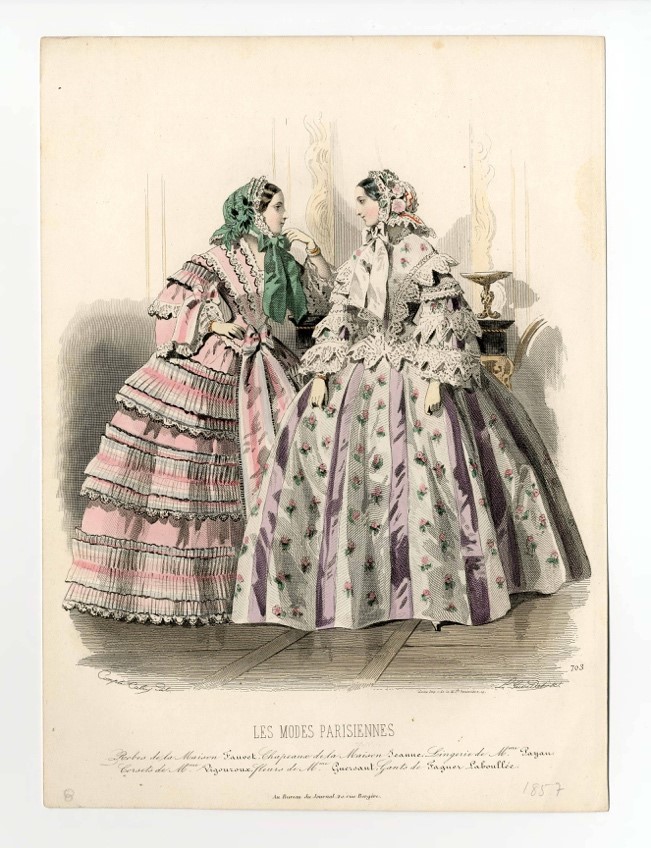

She is wearing a floral-patterned dress of luxurious Lyonaise silk. Her bodice is beribboned and fitted to her waist while the voluminous skirt is supported and enlarged either by numerous petticoats or by a crinoline cage in line with the fashionable silohuette of the time (Fig. 5) (Mackrell 80). It is uncertain whether she has adopted the newest stiffened cage crinoline, which was introduced in 1856 to take the place of multiple, cumbersome petticoats (Fig. 6) (Bruna 178-179). Whatever the case, the full skirts required by the fashion of the day, along with the high placement of Madame Moitessier within the painting, enables the full display of the resplendent floral fabrics. Alice Mackrell mentions this fabric in her book Art and Fashion:

“The dazzling floral design of Madame Moitessier’s dress was achieved by advances in technology in the textile industry. The invention of the Jacquard loom made possible the production of elaborate woven patterns in threads colored by new, bright aniline dyes.” (80)

Alongside the development of automated weaving machines, the production of new colors saw significant advances in the 1850s. David Smith, a Halifax dyer, wrote a practical book on dyeing in 1851, covering about 800 recipes derived from three primary colors (Kay-Williams 138). It book was first published in Philadelphia and then translated into France, and was “possibly the first book on dyeing to go from English to French” (138). The circulation of the book as well as the jacquard loom gave new impetus to the French textile weaving industry.

French Empress Eugénie, who was the trendsetter and the absolute fashion icon of the 1850s and 1860s, helped popularize these new colors and brocade fabrics (Franklin). At the request of her husband, Emperor Napoléon III, who aimed to stimulate the textile manufacture in Lyons, the Empress Eugénie began to wear the brocaded Lyonnaise silk fabrics. Eugénie was also fascinated with queen Marie-Antoinette (1755-1793) and 18th-century fashion, leading to a revival of 18th-century inspired designs, particularly delicate Rococo flower patterns (Fig. 7) (Rabinow 440).

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown. Les Modes Parisiennes, vol. 38, no. 16 (February 1856). Source: Los Angeles Public Library

Fig. 6 - Artist unknown. Crinoline, its Difficulties and Dangers, ca. 1860. London: Museum of London. Source: Museum of London

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown. Empress Eugénie’s Bodice, reproduction of dress in the Portrait of the Empress Eugénie and her Maids of Honour, ca. 1850-55. Silk, wrap-printed chine, trimmed with silk blonde lace. Barnard Castle: The Bowes Museum. Source: The Bowes Museum

Fig. 8 - François Claudius Compte-Calix (French, 1813-1880). Les Modes Parisiennes, no. 807 (1855). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: The Met

Fig. 9 - François Claudius Compte-Calix (French, 1813-1880). Les Modes Parisiennes, no. 703 (1857). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: The Met

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown. Evening dress, ca. 1860. Tokyo: Bunka Gauken Costume Museum. Source: Pinterest

Due to the considerable influence of the empress’ taste, the flowered Lyonnais silk was soon coveted by fashionable women like Madame Moitessier and undisputedly recognized as the “latest statement of high-Parisian fashion” (Figs. 8-10) (Riopelle). As mentioned above, Ingres’s restyling of Madame Moitessier’s costume, therefore, aligned with this trend in French fashion. Her dress, with Rococo patterns akin to those worn by Madame de Pompadour in Drouais’s 1763 portrait (Fig. 11), embodied stylish elegance and represented the opulent consumption of the Second Empire. The painting itself was considered as “a living advert of Lyonnais silk industry” (Mackrell 80; Kay-Williams 138).

The bertha (that is the wide trimmed collar on the bodice) was also favored by Empress Eugénie. During the 1850s, the most frequently seen bertha design was filled with a large amount of lace attached at the top of the décolleté bodice, like the one seen on the black dress in Madame Moitessier’s standing portrait (Fig. 1). Lace was expensive and a representation of luxury in the nineteenth century, but one that was slowly being devalued with the advent of machine-made lace. In this seated portrait, lace appears only on the edge of her deep neckline and short evening sleeves (it could be from a lace-edged chemise). As an alternative, her bertha features colored tassel passementerie, which spreads from the bow in the center of her bodice to the outer edges (Thieme 37). Floral ribbons hang from both shoulder and the center-front bow. These voguish trims emphasize the newly created fabrics even further (Mackrell 80).

Coordinating with the dress, Madame Moitessier’s jewelry continues to amplify her opulence by “show[ing] her adherence to le style troubadour” (troubadour style), a Renaissance-revival style popular in the nineteenth century (Mackrell 80). A gold-and-enamel Renaissance-style brooch, which resembles one worn by Queen Mary I (Fig. 12), is centrally placed on her bodice. A gold, diamond, and emerald bangle adorns her left arm, succeeding with a cabochon amethyst bracelet studded with diamonds, while a garnet, Byzantine-style bracelet appears on her right arm (Fig. 13). The jewelry exhibits her tremendous wealth, though some see it as evidence of further classicizing by Ingres (Rabinow 440-441). With the elevation of Napoleon III to Emperor, the Second Empire saw the resurgence of antique luxury just as it had under the first Emperor Napoleon earlier in the century.

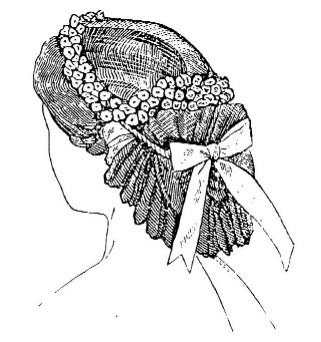

The sitter’s hair is pulled back off the brow and partially reveals her ears. While the portrait dates to the middle of 1850s, Madame Moitessier’s hairstyle like those earlier in the decade features a center part with the hair arranged heavily on the sides as seen in her standing portrait (Fig. 1), yet is fashion forward to the late 1850s and early 1860s style, in which hair gradually lowered at the back (Fig. 14) (Franklin).

Madame Moitessier’s evening dress manifests her fashionable and elegant taste, featuring the essential elements of 1850s fashion–from its floral silk brocade fabric to its wide, off-the-shoulder bertha and its Renaissance-revival jewelry.

Fig. 11 - François-Hubert Drouais (French, 1727-1775). Portrait of Madame de Pompadour, 1763-4. London: The National Gallery. Source: The National Gallery

Fig. 12 - Hans Eworth (Flemish, 1520-1574). Queen Mary I, 1554. Oil on panel; 21.6 x 16.7 cm (8.5 x 6.6 in). London: National Portrait Gallery. Source: National Portrait Gallery

Fig. 13 - Artist unknown. Chormosaiken in Theodora und ihr Hof., Unknown date. Mosaic. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 14 - Artist unknown. Coiffure, Godey's Lady's Book, September 1863. Source: Vintage Victorian

Its Legacy

B

y 1870, the silk production in Lyons occupied 75% of the total industrial activities there with hundreds of thousands of looms in operation (Invest in Only Lyon). It was recognized as the world’s “silk capital” and has maintained its reputation for its silk-weaving industry until today. A number of high fashion brands, such as Hermes and Chanel, manufacture their luxury silk goods there, continuously fueling its silk industry. And the floral patterns popular in the 18th and 19th centuries continue to enchant, regularly featuring in fashion designers’ repertoires, such as the couture gowns shown in figures 15-16.

Fig. 15 - Jeremy Scott (American, 1975-present). Moschino Fall/Winter 2020 Fashion Collection, February 2020. Milan Fashion Week. Source: The Impression

Fig. 16 - Pierpaolo Piccioli (Italian, 1967-present). Valentino Gown, Spring/Summer 2019. Source: Vogue

References:

- Bruna, Denis, ed. Fashioning the Body: An Intimate History of the Silhouette. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/90754730

- Franklin, Harper. “1850-1859.” Fashion History Timeline, February 19, 2020. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1850-1859/.

- “Ingres and French Art Law” in The Art Journal. United Kingdom: Virtue and Company, 1878. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/5542701839

- Rabinow, Rebecca A. Portraits by Ingres: Image of an Epoch, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1110798864

- “Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres: Madame Moitessier: NG4821: National Gallery, London.” The National Gallery, January 1, 1970. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/jean-auguste-dominique-ingres-madame-moitessier.

- Invest in Only Lyon. What Is the History of Silk in Lyon? Retrieved from https://www.aderly.com/history-silk-lyon/index.html

- Kay-Williams, Susan. “Ryots, Rewards and Handsome Colours: the 19th Century” in The Story of Colour in Textiles: Imperial Purple to Denim Blue, 137-148. London: Bloomsbury, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/973534569

- Mackrell, Alice. Art and Fashion. United Kingdom: Pavilion Books, 2005. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/316202486

- Rosenblum, Robert. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. New York, 1967. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/246377143

- Riopelle, Chris. “Ingres’s Madame Moitessier” in Talks for All. The National Gallery, 2019. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/jean-auguste-dominique-ingres-madame-moitessier#VideoPlayer95762

- Shelton A.C. “Ingres Versus Delacroix.” Art History 23, no. 5 (December 2000): 726–742. http://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2055/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=4335182&site=ehost-live

- Thieme, Otto C., Elizabeth A. Coleman, Michelle Oberly, and Patricia Cunningham. With Grace and Favor: Victorian & Edwardian Fashion in America. Cincinatti: Cincinatti Art Museum, 1993. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/729671763