This cream patterned dress trimmed with pleated green ribbons was considered a fashionable garment in 1862 with its full crinoline skirt and simple, but deliberate trimmings.

About the Look

T

his French 1862 dress is made of a cream patterned silk and features a full crinoline skirt (Fig. 1). The pattern consists of a repeat of a row of straight brown lines interspersed with a floral motif, a simple polka dot, and a light floral half-drop pattern (Fig. 2). Most of the fullness is towards the back of the skirt compared to the front that is a bit more flat (Fig. 3). The bodice is vest-like and there are eight mint fabric-covered buttons run down the center of the vest to hold it together. From the last button down, it is trimmed with mint pleated silk with a thin gold ribbon running through it all around to the back of the bodice, similar to the trim used on the full skirt edged with dark brown silk.

The trim used evenly along the hem of the skirt is a bit more complex with the pleated mint and separate gold ribbon are a bit thicker, and every few inches, there is a cream, forest green, and mint green ribbon that runs perpendicularly to the horizontal trim (Fig. 4). The trim peaks into a triangular shape five times around the hem of the skirt and the angled lengths of the trim are connected by a gold and green rope that criss-crosses between the two sides. At the two ends of the rope are tassels that graze the hem of the skirt.

A zouave-style jacket is worn over top of the dress and is made of the same patterned silk and has the same trim down the center front and on the sleeves as well. The sleeves are low-set and are curved slightly around the cuff area and peak at the back, making the trim come together at a sharp point (Fig. 5) It also comes to a sharp point at the front of the sleeve much in the same way as it does in triangular shapes along the hem with the criss-crossed ropes and tassels (Fig. 6).

Fig. 1 - Designer unknown (French). Dress, 1862. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973.244.1a–c. Gift of Katharine S. Pearce, 1973. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (French). Dress, 1862. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973.244.1a–c. Gift of Katharine S. Pearce, 1973. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (French). Dress, 1862. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973.244.1a–c. Gift of Katharine S. Pearce, 1973. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (French). Dress, 1862. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973.244.1a–c. Gift of Katharine S. Pearce, 1973. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 5 - Designer unknown (French). Dress, 1862. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973.244.1a–c. Gift of Katharine S. Pearce, 1973. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (French). Dress, 1862. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973.244.1a–c. Gift of Katharine S. Pearce, 1973. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Dress, 1862. Cream and mint silk dress. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973.244.1a–c. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

About the context

The zouave-style jacket was very fashionable at the time, as discussed in a September 1862 issue of The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine:

“The short cut-away jackets appear to be now the prevailing mode for dress bodies, in many materials, both for ladies and children; and the fashion certainly is stylish and becoming.” (237)

In the same issue, while describing another dress, the editor mentions that its “body is made in the mode that is now extremely fashionable – namely, the short cut-away Zouave…” (238), making it clear how coveted of a silhouette the zouave-style jacket was in 1862.

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown (American). White cotton piqué afternoon dress, 1867. White cotton piqué and black cotton cording. New York: Museum at FIT, P90.22.2. Museum purchase. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 8 - Designer unknown (American). Printed Silk dress, 1859-1869. Printed silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 9 - Designer unknown (American). Dressing gown, ca. 1860. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.60.6.6. Gift of Chauncey Stillman, 1960. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

FIT’s white cotton piqué afternoon dress (Fig. 7) has a very similar zouave-style jacket and bodice as the original cream and mint day dress–a style that Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine also notes was popular with morning dresses in a June 1862 issue (618). Though made of a different fabric meant for a different occasion, it is undeniable that the silhouettes are very similar. The black cotton cording is placed along the front of the jacket and all around the hem of the skirt, much like the placement of the mint trimmings on its 1862 cousin. Even the triangular peaks of the black cording are similar.

Despite having a more prominent floral pattern, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s printed silk dress from the 1860s (Fig. 8) is comparable with its similar cream and mint coloring, low-set sleeves, and ruched ribbon trimmings.

Another notable example from the Met’s collection is a cream dressing gown from 1860 (Fig. 9) that has similar four-stranded trimmings that break off at angles, an understated floral pattern, and low-set sleeves that also have a bit of volume.

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown. Robe à Transformation, 1865. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 11 - Artist unknown. Moniteur de la Mode, Thursday, January 1, 1863. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Public Library, v. 43, plate 14. Source: Los Angeles Public Library

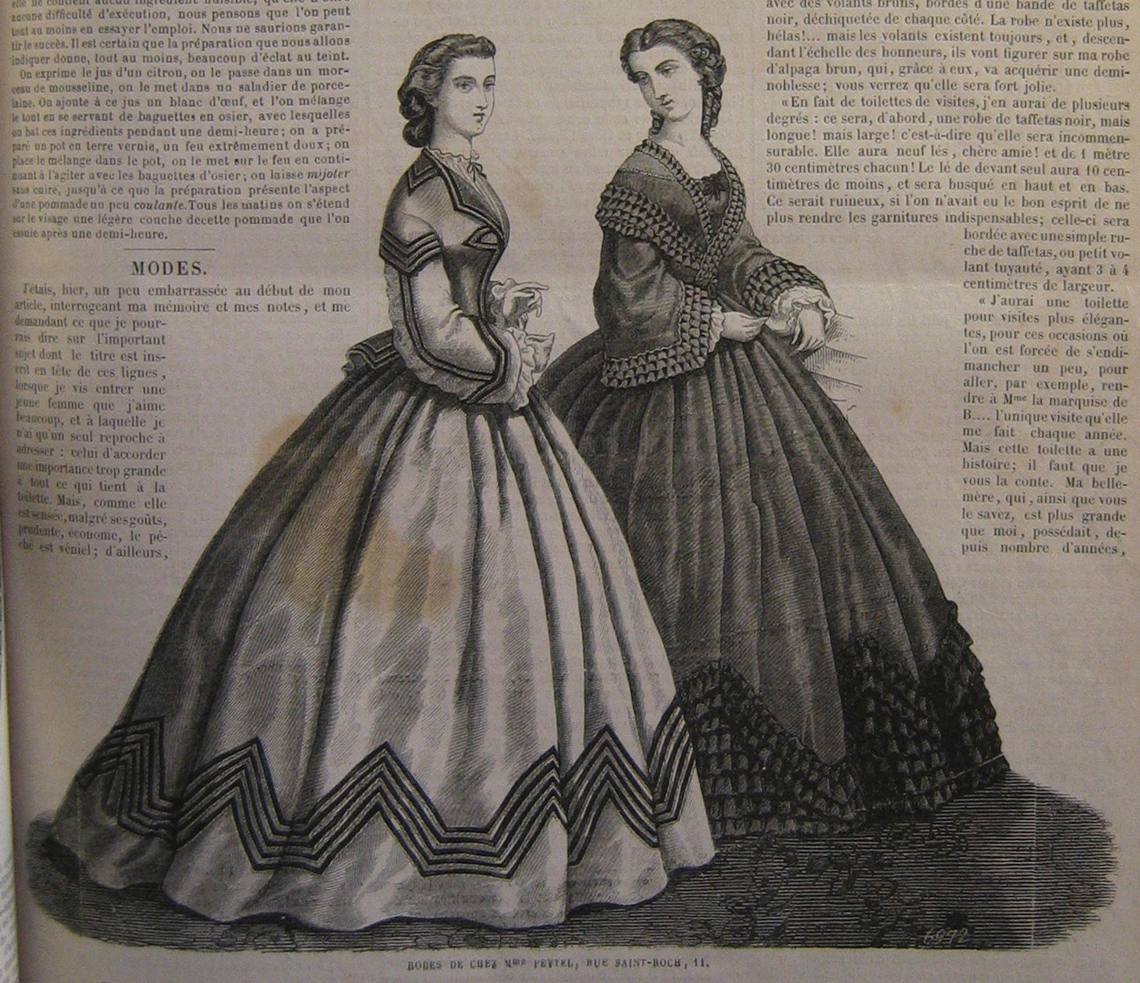

Fig. 12 - Artist unknown. La Mode Illustrée Fashion Plate, vol. 3, no. 4 (January 1862). Source: Google Books

Although made for a fancier occasion, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s dress from 1865 (Fig. 10) features the same cream and green coloring and similar tassel trimmings, though more elaborate. The lace trim peaks at certain points along the hem of the skirt in the same way that the 1862 dress does.

A fashion plate from Le Moniteur de la mode‘s January 1863 issue (Fig. 11) also features a similar dress in white with a light floral pattern and green ruched ribbon trimmings comparable to the 1862 day dress.

The cream and mint day dress has a light but elaborate pattern that makes the need for elaborate trimmings not necessary. Other solid-colored dresses from this time period that often relied on voluminous ruffle and bow trimmings to be considered fashionable, though the simplicity was not limited to patterned dresses as can be seen in figures 7 and 9, and also in La Mode illustrée’s fashion plates (Figs. 12-15).

Fig. 13 - Artist unknown. La Mode Illustrée Fashion Plate, vol. 3, no. 36 (September 1862). Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Fig. 14 - Artist unknown. La Mode Illustrée Fashion Plate, 1862. Source: Schlesinger Library

Fig. 15 - Artist unknown. La Mode Illustrée Fashion Plate, 1862. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Something similar to the mint trim from the original dress with the peculiar multi-colored ribbon running perpendicular to the four-stranded trim that graced the hem of the dress can be found on the right side of another fashion plate from La Mode illustrée (Fig. 16). Though not identical as the horizontal embellishments stand alone and seem to be a bit more complex and Mandarin-like at the two ends, the effect created is similar.

Monet’s Women in the Garden from 1865 (Fig. 17) show similar day dresses in light colors and simple patterns and trimmings. The white and green pinstripe dress on the left aptly shows the popular style of the 1860s where the fullness of the skirt is more towards the back as opposed to being equally full all around. The low-set sleeves are also especially clear in white and green pinstripe dress on the left as well as that of the woman sitting on the grass. Despite the fullness of her skirt, the crinoline skirt that is likely worn underneath helped make it possible to sit gracefully and comfortably due to its light weight, as Birgit Haase notes in Impressionism, Fashion, & Modernity:

“The wide bell shape of the skirt is supported by a crinoline of connected metal hoops. Crinolines replaced layered petticoats in the late 1850s and provided lightweight sculpting for the period’s ever-increasing skirt dimensions.” (85)

Fig. 16 - Artist unknown. La Mode Illustrée Fashion Plate, vol. 3, no. 36 (September 1862). Source: Google Books

Fig. 17 - Claude Monet (French, 1840-1892). Women in the Garden, 1866. Oil on canvas; 255 x 205 cm. Paris: Musée d'Orsay, RF 2773, LUX 1360. Source: Musée d'Orsay

Its Afterlife

This dress has been featured in two exhibitions at the Met: “Vanity Fair: A Treasure Trove from the Costume Institute” from December 15, 1977 to September 3, 1978, and “Costume in the Age of Ingres” from September 9, 1999 to November 21, 1999. It also traveled to the Saint Louis Art Museum for an exhibition entitled “Vanity Fair: Four Centuries of Fashion from The Metropolitan Museum of Art” from February 3, 1979 to April 1, 1979.

References:

- “Fashions.” Godey’s Magazine 64 (June 1862). https://books.google.com/books?id=-YBMAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=fashions&f=false.

- Haase, Birgit. “Fashion En Plein Air.” In Impressionism, Fashion, & Modernity, edited by Gloria Groom. Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/878842920.

- “The Fashions.” The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine 5 (September 1862). https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015022690567;view=1up;seq=251;size=75.