This striking plaid ensemble designed by Elizabeth Keckley for Mary Todd Lincoln was on the cutting edge of fashion, but also in good taste – embracing the latest French trends while relying on a distinctively American plaid and minimal trimmings in light of the ongoing Civil War.

About the Look

This dark green and white buffalo wool plaid day dress was designed by Elizabeth Keckley and worn by First Lady Mary Lincoln in 1862. The three-piece ensemble includes a day bodice and skirt and a matching cape-style coat; the same fabric is used in all three garments.

The fitted day bodice is relatively plain; it closes at center front with six large black wool buttons and a braid-edged placket. The bodice has long sleeves with 5 lines of black wool braid trim at the sleeve edges and a low collar also edged in black wool braid. The bodice and skirt meet at the natural waist, which is accentuated by a wide belt also edged in wool braid and closed with two more matching buttons.

The large bell-shaped skirt shape would have been supported by a crinoline cage. The slightly fuller curve to the back of the skirt (Fig. 1) was fitting for the time, as Harper Franklin explains in her summary of 1860s fashions: “the cage began to swing toward the back, becoming pyramid-shaped, the silhouette for the majority of the decade.” The skirt features the same large black buttons down the front of the skirt and black braid trim down the center front and at the skirt hem. It also includes two oversized pockets on each side of the skirt with the flaps closed by black buttons at the edges.

The simple cape (Fig. 2) clasps under the bodice collar and covers the torso and arms. It is closed by a single button at the throat.

The matching cape and wool material suggest that this garment was worn in the wintertime. Wool was often used throughout the Civil War period due to it being a warm yet breathable fabric, making it perfect material for the busy First Lady who was trying to help soothe the warring country (Hodakel).

Fig. 1 - Elizabeth Keckley (American, 1818-1907). Day dress, 1862. Chicago History Museum: Costume and Textiles collection. Source: Chicago History Museum

Fig. 2 - Elizabeth Keckley (American, 1818-1907). Day dress, 1862. Chicago History Museum: Costume and Textiles collection, ICHi-066122. Source: Chicago History Museum

Elizabeth Keckley (American, 1818-1907). Day Dress, 1862. Green and white buffalo plaid, black wool braid. Chicago: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-066126. Source: Chicago History Museum

About the context

This garment was worn by First Lady Mary Lincoln (Fig. 3), wife of American President Abraham Lincoln, and designed by Elizabeth Keckley (Fig. 4). Keckley was born enslaved but gained freedom when a dress-making client paid $1,200 for her and her son George to be freed. Keckley moved to Washington DC where she had a studio and made dresses for political elites. In the early 1860s she met Mary Lincoln and became the favored dressmaker for the First Lady. Over the years, the pair became very close as Keckley designed Lincoln’s most famous garments. [Read our designer profile to learn more and see other dresses she designed!]

The garment dates to ca. 1862 in the midst of the Civil War, which explains the simple design that was typical of the time out of respect for the distress the country was experiencing. The dress uses a patterned plaid fabric which catches the eye but doesn’t need lavish accents. Trimming in America during this time was minimal according to Godey’s Magazine (Nov. 1862):

“one narrow flounce, a few rows of braid or velvet, a braided pattern, or a narrow quilling of ribbon seems indispensable.” (400)

That sense of minimalism is clear in an American fashion plate from March 1862 (Fig. 5). The gray dress at left features the same large black buttons down the center front and similar black trim edging that Keckley’s dress does.

A slightly earlier surviving plaid dress from ca. 1859 garment (Fig. 6) is more daring in its colors and slightly more lavishly adorned. The bodice meets the skirt at a distinct point, but the ensemble resembles Keckley’s nonetheless. There is the pronounced line of buttons down the front of both gowns that serve as the main focal point for the garments, in addition to a subtle trim at the end of the sleeves and skirt.

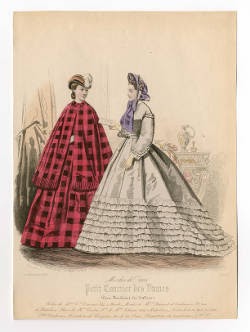

The choice of a Scottish tartan for the fabric of the ensemble was very fashionable in late 1862 and only would become more so in 1863. A November 1862 fashion plate from Petit Courrier des dames (Fig. 7) includes a woman on the left wearing a very similar three-piece ensemble in red and black buffalo plaid. The high collared bodice and cape closely resembles the top half of Lincoln’s ensemble. The detailing of these garments are similar in the sense that they are both minimal. Where Lincoln’s dress uses buttons down the front of the dress and a single button on the cape, the red ensemble has no visible buttons on the dress and four small ones on the cape; it has no applied braid trim, but features a fringed trim at the bottom of the cape.

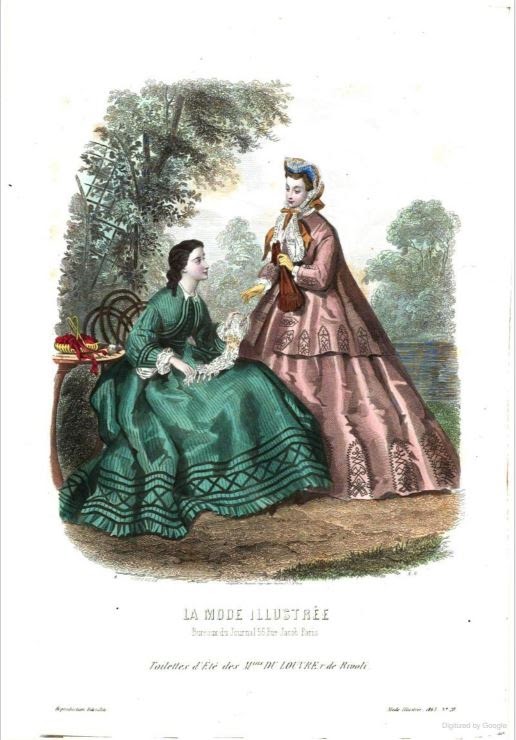

The plate (Fig. 7) also demonstrates the fashion for coordinating outerwear; another example can be seen in a May 1863 La Mode illustrée plate (Fig. 8), in which the standing woman on the right is seen in a matching three-piece ecru ensemble. The light silk taffeta fabric and delicate black embroidery at the bottom of the skirt at coat cuffs and edges reflect the more elaborate decorative aesthetic popular in France, which was not at war.

A December 1862 article in La Mode illustrée noted the popularity of Scottish plaids:

“We also see the reappearance of Scottish checkered fabrics quite generally.” (398)

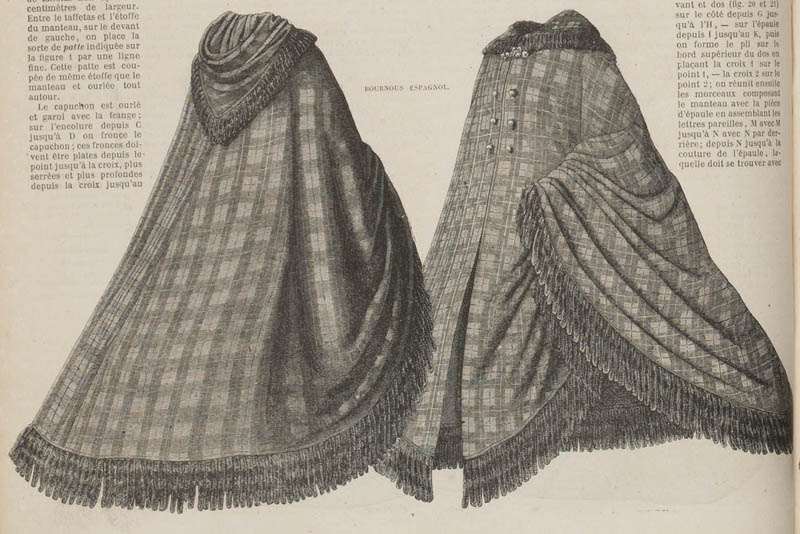

The popularity of tartan fabrics, which came from Scotland, hence the name “Scottish plaid” (or “carreaux écossais” in French), increased in the upcoming months and year as was frequently remarked in La Mode illustrée, the leading French fashion magazines of the day. For example, an October 1863 issue discusses the fashion for Scottish checked coats (331-332) and illustrates one (Fig. 9). The next issue writes that:

“Scottish checked fabrics in all dispositions are among the newest things generally adopted at this moment” (339).

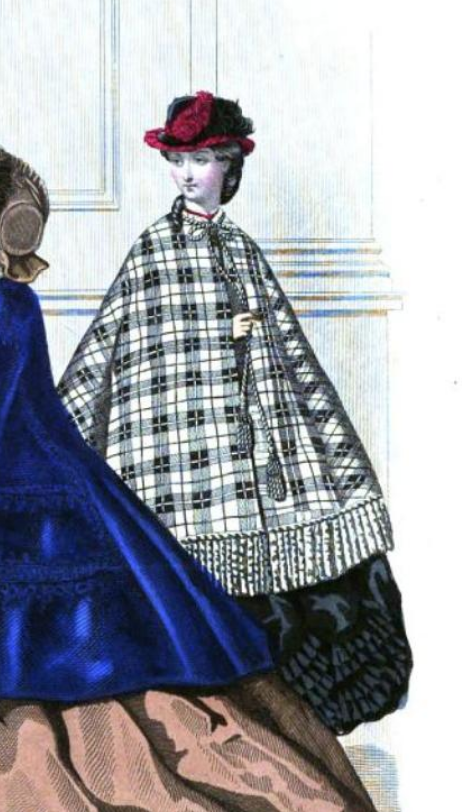

A November 1863 article noted that the fabric was “everywhere,” even being employed for “les robes du soir” or evening dresses (349). In November 1863, a cape similar to Lincoln’s featured in the color plates of La Mode illustrée advertising the latest coats from the Magasins du Louvre department store (Fig. 10). While Lincoln’s cape was dark green, this version is black and white and is much longer. It’s labeled as a “Grande Rotonde” which hangs longer over the skirt (374); Lincoln’s cape is more of a pelerine length, which is shorter.

Also in November 1863, La Mode illustrée published an illustration of a coordinated three-piece ensemble featuring Scottish plaid in violet, black and white (Fig. 11), where the cape was entirely of the plaid fabric and skirt had the same fabric used as a decorative band.

Keckley’s chosen plaid had particularly American connotations as the name “buffalo plaid” suggests. As the Scottish Tartans Authority explains, Jock McCluskey, an American descendant of Rob Roy, a Scottish folk hero, helped popularize the fabric in America where he traded blankets made of the tartan with the Native Americans. It soon became labeled buffalo plaid after that distinctively American plains animal, but in French magazines a similar plaid was simply labeled Scottish.

In conclusion, this ensemble designed by Keckley was not only fashionable for the time period, but on the cutting edge of fashion – embracing the latest French trends but relying on a distinctively American plaid.

Fig. 3 - Matthew Brady (American, 1823-1896). Mary Todd Lincoln, Dance Card, 1861. Photographic print : albumen, on carte visite moun. Washington DC: Library of Congress. Source: LOC

Fig. 4 - Photographer unknown (American). Elizabeth Keckley, taken at the Jefferson Fine Art Gallery in Richmond, VA, ca. 1890. Fort Wayne: Lincoln Financial Foundation. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown. Les Modes Parisiennes, March 1862. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17509853. Gift of Woodman Thompson. Source: The Met

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown. Blue & Purple Silk Plaid Day dress, ca. 1859. Source: Augusta Auctions

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown (illegible) (French). Petit courrier des dames, pl. 3357, November 21, 1862. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17509853. Costume Institute Fashion Plates. Gift of Mary P. Hayden. Source: The Met

Fig. 8 - Artist unknown (French). La Mode illustrée, no. 20, May 18, 1863. Source: Google Books

Fig. 9 - Artist unknown. "Bournous espagnol" in Scottish plaid. La Mode illustrée, no. 42 (October 19, 1863): 332. Source: Google Books

Fig. 10 - Artist unknown (French). Coats from the Magasins du Louvre, La Mode illustrée, November 23, 1863. Source: Google Books

Fig. 11 - Artist unknown. Toilette de Voyage. La Mode illustrée, no. 48 (November 30, 1863): 381. Source: Google Books

Its Afterlife

The garments Keckley designed and Lincoln wore are in museums today, but they are perhaps best known today in reproduction. A version of the buffalo plaid day dress appeared in the 2013 film Lincoln (Fig. 12). Johanna Johnston was nominated for an Oscar for the costumes in the film.

In a Vanity Fair profile, Marnie Henel explains that Johnston studied the extant garments, including those at the Chicago History Museum:

“Johnston found a dress at the Chicago History Museum and worked with collection manager Meghan Smith to measure it in detail. The pair discovered that the dress measured 30 inches on the inside of the waist.”

By using the exact clothing once worn by the Lincoln family, Johnston recreated fashion history and honored Keckley’s dressmaking achievement.

Fig. 12 - Joanna Johnston (English). Recreated Lincoln dress, 2013. Source: Vanity Fair

References:

- “Bournous.” La Mode illustrée, no. 42 (October 19, 1863): 331-32. https://books.google.com/books?id=-xl0bRLQtSwC&pg=PA331

- “Buffalo Plaid – Its Origins.” Buffalo Plaid origins | Scottish Tartans Authority. Accessed August 4, 2020. http://www.tartansauthority.com/tartan/tartan-today/buffalo-plaid/.

- “Elizabeth Keckley: White House Dressmaker, Author, and Civil Activist.” Chicago History Museum, May 26, 2020. https://www.chicagohistory.org/elizabeth-keckley-white-house-dressmaker-author-and-civil-activist/.

- “Fashions for November”. Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine (Online) vol. 64 (November 1862): 400. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015016441498&view=1up&seq=64.

- Franklin, Harper. “1860-1869.” Fashion History Timeline, December 27, 2019. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1860-1869/.

- Hanel, Marnie. “How Lincoln’s Oscar-Nominated Costumes (and Sally Field’s Weight Gain) Made an Eerily Real Presidential Couple.” Vanity Fair, 2013. https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2013/01/lincoln-oscar-nominated-costumes-sally-field.

- Hodakel, Boris. “What Is Wool Fabric: Properties, How It’s Made and Where.” Sewport. Sewport, June 10, 2019. https://sewport.com/fabrics-directory/wool-fabric.

- “Manteaux des Magasins du Louvre.” La Mode illustrée, no. 47 (November 23, 1863): 374. https://books.google.com/books?id=-xl0bRLQtSwC&pg=PA374

- “Modes.” La Mode illustrée, no. 49 (December 7, 1862): 398. https://books.google.com/books?id=Yx0VYawuzrwC&vq=ecossais&pg=PA398

- “Modes.” La Mode illustrée, no. 43 (October 26, 1863): 339. https://books.google.com/books?id=-xl0bRLQtSwC&pg=PA339

- “Modes.” La Mode illustrée, no. 44 (November 2, 1863): 349. https://books.google.com/books?id=-xl0bRLQtSwC&pg=PA349.