About the Designer

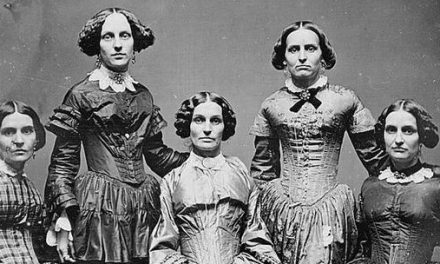

Elizabeth Keckley, a remarkably successful dressmaker, built her career upon exacting technical standards, graceful clean lines, and an understanding of Parisian fashionable trends (Fig. 1). She is well known for her work for the political elite of Washington D.C., particularly for Mary Todd Lincoln. Keckley was one of the first African American women to publish a book (Wartik) and was an impassioned activist who created a relief organization for newly freed enslaved persons (Keckley 115).

Thanks to Keckley’s 1868 autobiography, Behind the Scenes, or, Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House, the details of her life are well documented. She was born in Virginia in 1818. Keckley was the illegitimate daughter of Armistead Burwell, who held her and her mother, Agnes Hobbs, in slavery (Wartik). She was taught dressmaking skills by her mother (Way 116). After surviving sexual abuse, she gave birth to her son, George (Keckley 38-39). Keckley was forcibly moved to St. Louis along with her mother and son (Keckley 44). She became the primary supporter of her enslavers by starting a dressmaking business (Keckley 45). In 1855, she was able to purchase her and her son’s freedom and moved to Washington D.C. (Keckley 59-60).

In the 1860s, a thriving community of Black dressmakers was emerging in Washington (Reynolds 5). Through her dressmaking business, Keckley built her reputation for her exemplary work ethic and her thoughtful designs for the wives of the political elite (Santamarina 516). By chance, Keckley was introduced to Mary Todd Lincoln, wife of President Abraham Lincoln. After a spilled coffee, Mary Lincoln required a new gown (Fig. 2) for her husband’s inauguration, and fast (Keckley 80). The two developed a close friendship, and Keckley became Lincoln’s primary dressmaker. In the spring and summer of 1861, Keckley made fifteen dresses for Lincoln (Keckley 90). Keckley built a large-scale business; she employed twenty-five seamstresses in 1865, and tax records show that she was generating a large profit (Reynolds 11,13).

Fig. 2 - Mathew Brady (American, 1823-1896). Mary Todd Lincoln, Dance Card, 1861. 1 photographic print : albumen, on carte de visite moun. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. Source: LOC

Fig. 1 - Photographer unknown (American). Elizabeth Keckley, taken at the Jefferson Fine Art Gallery in Richmond, VA, ca. 1890. Fort Wayne: Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection. Source: New York Times

Along with her work in fashion, Elizabeth Keckley was an activist for formerly enslaved African Americans. In 1862, Keckley founded the Contraband Relief Organization, which was a fund to support struggling Black Americans who had recently migrated to Washington (Keckley 111). She worked alongside Frederick Douglass and collected funds to support those who lacked basic necessities (Library of Congress).

Unfortunately, after Mary Lincoln’s “Old Clothes Scandal” in 1867, Keckley and Lincoln had a falling out. After the death of Abraham Lincoln, Mary Lincoln was heavily in debt and asked Keckley to aid her in selling her extravagant wardrobe (Keckley 323-327). The sale embarrassingly backfired, and Keckley published her book in part to clear Lincoln’s name (Santamarina 529). The publication of Keckley’s book was seen as a betrayal of Lincoln’s privacy. Many white Americans denied her status of being a successful Black dressmaker, and instead cataloged her as a vengeful servant (Santamarina 520). She soon left Washington and spent the later years of her life teaching at Wilberforce University in Ohio (Santamarina 534).

Today, only a limited number of Keckley dresses have survived. As her work predates the widespread use of labels (Way 128), garments can only be attributed to her through knowledge from the wearers and their descendants. Garments that are assumed to have been created by Keckley include Lincoln’s Strawberry Dress (see Gallery below), and a striped 1863 dress that was altered, possibly in the late 1860s (see Timeline essay).

Keckley had an eye for detail and her designs showed a polished elegance. As fashion historian Elizabeth Way notes, “looking at the details of Keckly’s limited number of extant garments, one aspect becomes clear: she appreciated clean lines and unpretentious designs.” In an 1861-62 purple velvet dress with both day and evening bodices designed for Mary Lincoln, white piping neatly traces along the back of the bodice down to the flowing train (see Timeline essay). Keckley’s use of contrasting binding in an 1862 plaid dress (see Gallery) gives it a striking geometry that appears distinctly modern in comparison to the lavish fashions of the 1860s. The use of bolder, more simplified shapes was uncharacteristic of the Victorian era, but in time, it began to typify American fashion (Way 113). Keckley’s work was early in the development of American designers’ distinction from their European counterparts. Despite the challenges she faced in her life, Elizabeth Keckley was influential on the visual culture of the 1860s, and the broader history of American fashion.

Timeline Essays (Click the images to read more):

Elizabeth Keckley (American, 1818-1907). Striped Evening dress for Mary Todd Lincoln, 1863. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. Source: Fashion History Timeline

Elizabeth Keckley (American, 1818-1907). Mary Lincoln's dress, 1861. Velvet with satin, lace, and mother of pearl buttons. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian National Museum of American History, 70138. Bequest of Mrs. Julian James. Source: Fashion History Timeline

Elizabeth Keckley (American, 1818-1907). Mary Lincoln's dress, 1861. Velvet with satin, lace, and mother of pearl buttons. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian National Museum of American History, 70138. Bequest of Mrs. Julian James. Source: Fashion History Timeline

Elizabeth Keckley (American, 1818-1907). Mary Todd Lincoln’s gown, ca. 1862. Wool. Chicago: Chicago History Museum, CHM ICHi-066126. Source: Fashion History Timeline

GALLERY

Elizabeth Keckley (American, 1818-1907). Strawberry dress, ca. 1862. Springfield: Lincoln Presidential Library. Source: Madison.com

Elizabeth Keckley (American, 1818-1907). Striped Evening dress for Mary Todd Lincoln, ca. 1863. Moiré silk taffeta. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. Source: Fashion History Timeline

To Learn more:

-

Keckley, Elizabeth. Behind the Scenes, or, Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House (version University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill). New York, NY: G. W. Carleton & Co., Publishers, 1868. https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/keckley/keckley.html.

- Library of Congress. “April 1862–November 1862 – The Civil War in America,” November 12, 2012. https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/civil-war-in-america/april-1862-november-1862.html#obj.

-

Reynolds, Virginia. “Slaves to Fashion, Not Society: Elizabeth Keckly and Washington, D.C.’s African American Dressmakers, 1860–1870.” Washington History 26, no. 2 (2014): 4-17. www.jstor.org/stable/23937711.

-

Santamarina, Xiomara. “Behind the Scenes of Black Labor: Elizabeth Keckley and the Scandal of Publicity.” Feminist Studies 28, no. 3 (2002): 515-37. DOI:10.2307/3178784.

-

Wartik, Nancy. “Overlooked No More: Elizabeth Keckly, Dressmaker and Confidante to Mary Todd Lincoln.” The New York Times, December 12, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/12/obituaries/elizabeth-keckly-overlooked.html.

- Way, Elizabeth. “Elizabeth Keckly and Ann Lowe: Recovering an African American Fashion Legacy That Clothed the American Elite.” Fashion Theory, 19:1, 115-141. DOI: 10.2752/175174115X14113933306905.