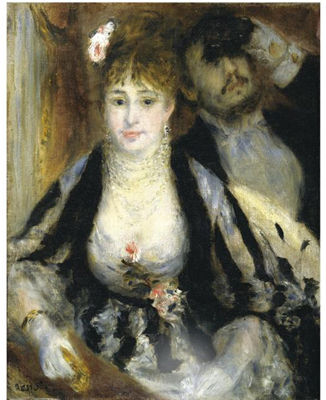

In Renoir’s Loge, he paints one of his favorite models Nini Lopez in a black and white striped dress in the context of a theater box–a fashionable dress style, but a questionable fit for the occasion. Her highly made-up face and disheveled hair also provoked discussion when the painting was exhibited at the Impressionists’ first group show in 1874.

About the Artwork

Pierre-Auguste Renoir was a French painter who was among those who started the Impressionist movement in the late 1860s. He was born in Limoges, France in 1844 and became an apprentice to a porcelain painter at 13 years old (Distel, Grove).

Before La Loge, paintings of theater boxes did not commonly exist, with Renoir’s depiction only preceded by Honoré Daumier (Fig. 1) and Constantin Guys’s versions (Fig. 2) in the form of small oil as well as watercolor paintings (Ireson 11). This fashionable setting was also one that Renoir revisited often in the following years, as John House discusses in his essay “Modernity in Microcosm: Renoir’s Loges in Context”:

“The theme of the theatre box played a central role in Renoir’s work through the crucial years of the Impressionist movement, between 1873 and 1880. It offered him the opportunity to explore the world of Parisian fashionable entertainments, and to focus on the glamorous women’s costumes and on the interplay of gazes and glances that animated the audience. His paintings of the theatre box were part of his larger project in these years to depict the most characteristic scenes and sights in modern Paris.” (27)

The sitter is Nini Lopez, one of Renoir’s favorite models from Montmatre (The Courtauld Institute of Art) who was nicknamed “guele de raie” or fish face, which “suggests that her face did not conform to current canons of beauty” (House 33). House further explains the origin of the nickname:

“In the imagery of the period, following contemporary physiognomic theory, fashionable women from a ‘good’ background were standardly depicted with wide-spaced eyes and delicate cheekbones, mouth and chin; in contrast to this stereotype, Renoir’s figure has a slightly puffy, bloated face and wide, fleshy mouth.” (32)

Nini’s male companion was posed for by Renoir’s brother Edmond; however, knowing the identities of the sitters does not make the relationship depicted between the two any less ambiguous since Renoir simply used them as models (IFM 38).

La Loge was produced in Renoir’s studio (The Courtauld Institute of Art) and was accompanied by a smaller 27.3 x 21.9 cm version (Fig. 3) that was sold at an auction in 1875 (House, van Claerbergen, Wright 72-74). Not much was changed except for a few minor details, outlined by John House, Ernest Vegelin van Claerbergen, and Barnaby Wright in the catalog of Renoir at the Theatre: A Look at la Loge:

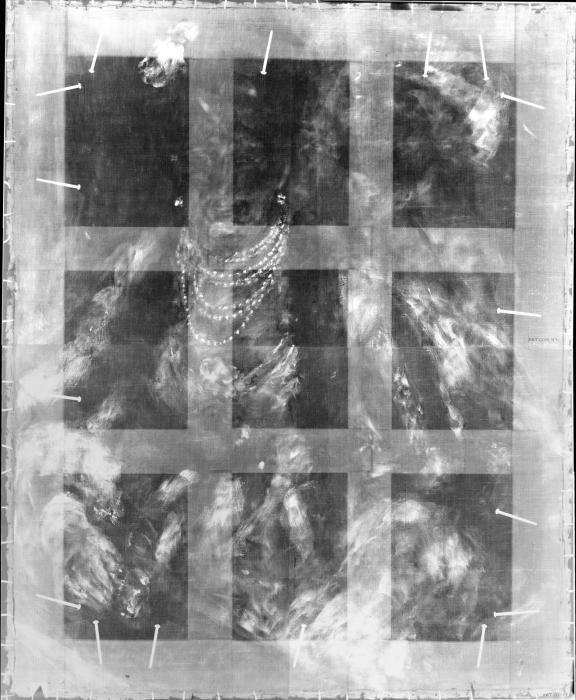

“The X-ray (Fig. 4) suggests that he may originally have given the female model a hat, and there are some minor changes to the position of the man’s arm.” (74)

This painting was exhibited in April 1874 at the first Impressionist show and was generally well received with critics praising the artistic techniques employed by Renoir, but there was something “ambiguous and potentially troubling about this figure”(House 28-29). Nini’s appearance seems to be an “illusion” of sorts because of her very pale and made-up skin, and the pleasant yet empty look in her eyes only further reinforces that (House 30), an idea further explored by House in the same essay:

“Three of the reviews quoted above comment on the fact that the female figure is depicted wearing make-up. Clearly, from their comments, this could be seen as suggesting that she was not all she seemed and that her glamorous garb masked her true identity.” (32)

In the catalogue of the 1985 Renoir retrospective, Anne Distel summarizes the critics’ reaction to the portrait, some a touch more positive:

“The critics who reviewed the 1874 exhibition dwelt on this painting at length and stressed its novelty. Prouvaire saw the woman as a typical cocotte, ‘one of those women with pearly white cheeks and the light of some banal passion in their eyes… attractive, worthless, delicious and stupid’. Montifaud, however, thought she was ‘a figure from the world of elegance.’ Their views are not, of course, necessarily contradictory. The obvious pleasure the painting gave them did not, however, make them overlook its purely pictorial qualities; on the contrary, Burty, Chesneau and especially Montifaud all praised them. It is noteworthy that none of the critics who reviewed the exhibition unfavourably attacked La Loge directly.” (203)

However, when it was first exhibited in 1874, the painting was reviewed by critics under La Loge, but also L’Avant-scène. This distinction complicated further complicated the interpretation of the painting, as explained by House:

“The avant-scène was technically the area of the stage in front of the drop curtain; by extension, the term came to be used to describe the boxes closest to, or directly above, this part of the stage. By designating this theatre box thus, Renoir was invoking a set of associations that are fundamental to understanding the uncertainties that the picture raised. The entry on Loge in Larousse’s Grand dictionnaire noted that the view from the avant-scène boxes, was the worst in the theatre, but commented, “The avant-scène boxes, whose occupants are exceptionally visible, are sought by people who pose and want to put on a show.” (34)

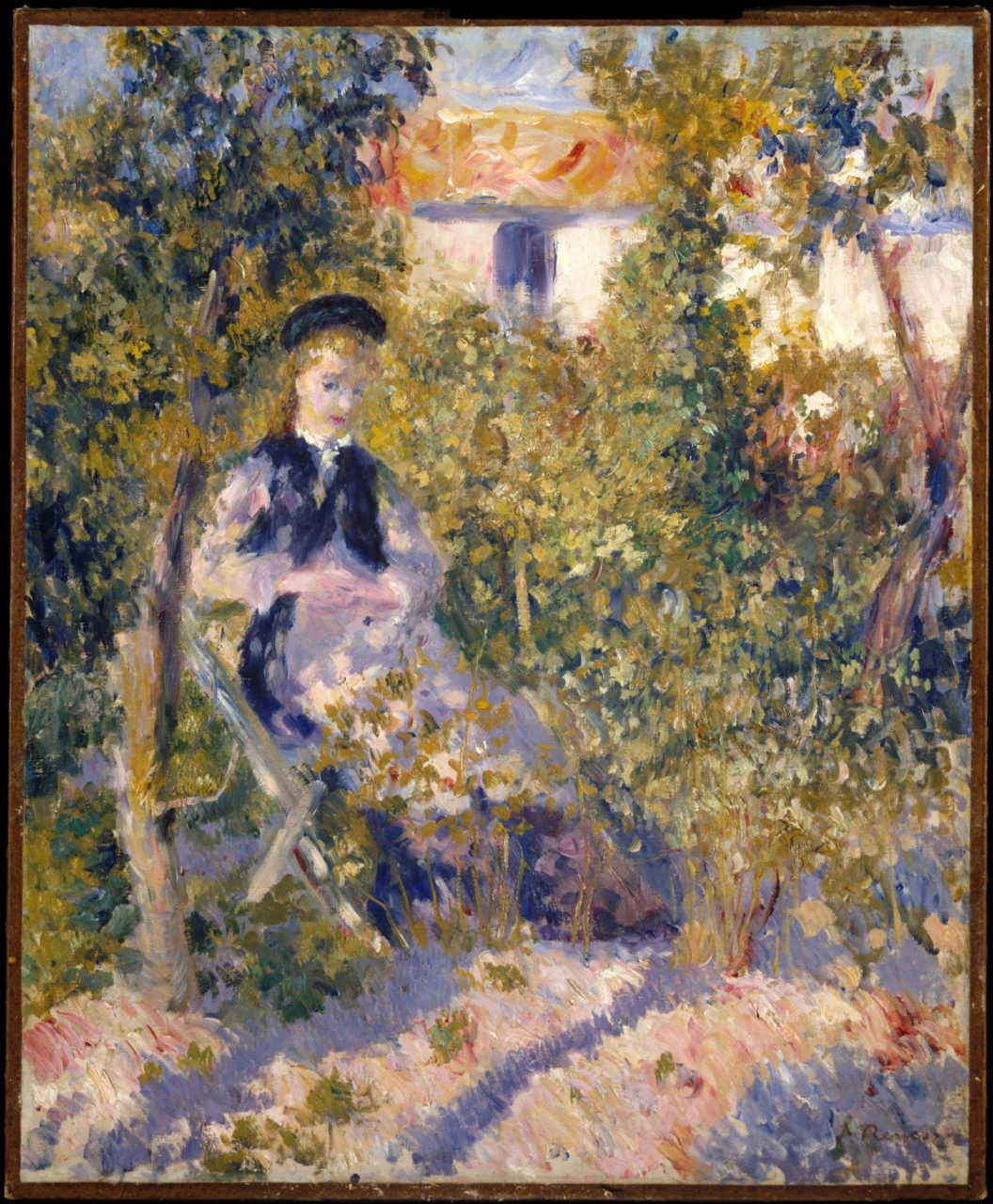

Nini Lopez also appeared in a number of other Renoir paintings including Woman at the Piano (1875-76) (Fig. 5) and the aptly titled Nini in the Garden or Nini Lopez (1876) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 1 - Honoré Daumier (French, 1808-1879). The Loge (In the Theatre Boxes), 1856-57. Oil on canvas; 24.1 x 30.7 cm (9 1/2 x 12 1/16 in). Baltimore: The Walters Art Museum, 37.1988. Source: The Walters Art Museum

Fig. 2 - Constantin Guys (Dutch, 1802-1892). The Loge, 19th century. Watercolor. Vienna: Albertina. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 3 - Pierre-Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919). La Loge (smaller version), 1874. Oil on canvas; 27.3 x 21.9 cm. Private Collection. Source: askART

Fig. 4 - Pierre-Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919). La Loge (X-Ray), 1874. Oil on canvas; 80 x 63.5 cm. London: The Courtauld Institute of Art. Source: The Courtauld Institute of Art: Art and Architecture

Fig. 5 - Pierre-Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919). Woman at the Piano, 1975-76. Oil on canvas; 93 x 74 cm (36 9/16 x 29 1/8 in). Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1937.1025. Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection. Source: Art Institute of Chicago

Fig. 6 - Pierre-Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919). Nini in the Garden, 1876. Oil on canvas; 61.9 x 50.8 cm (24 3/8 x 20 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2002.62.2. The Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg Collection, Gift of Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg, 2002, Bequest of Walter H. Annenberg, 2002. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (French, 1841–1919). La Loge, 1874. Oil on canvas; 80 x 63.5 cm (31 x 25 in). London: The Courtauld Gallery. The Samuel Courtauld Trust. Source: The Courtauld Gallery

About the Fashion

The female model, Nini, wears a white silk gauze “demi-toilette” evening dress in the “polonaise” or “polonaise-princess” style made popular in the 1870s. It consists of an overgrown skirt looped up at the sides and back and worn over a separate skirt. The dress also has appliquéd black ruched tulle and sleeve ruffles made of machine-made silk lace (Ribeiro 47). She also wears an ermine mantle thrown over her shoulders (IFM 39).

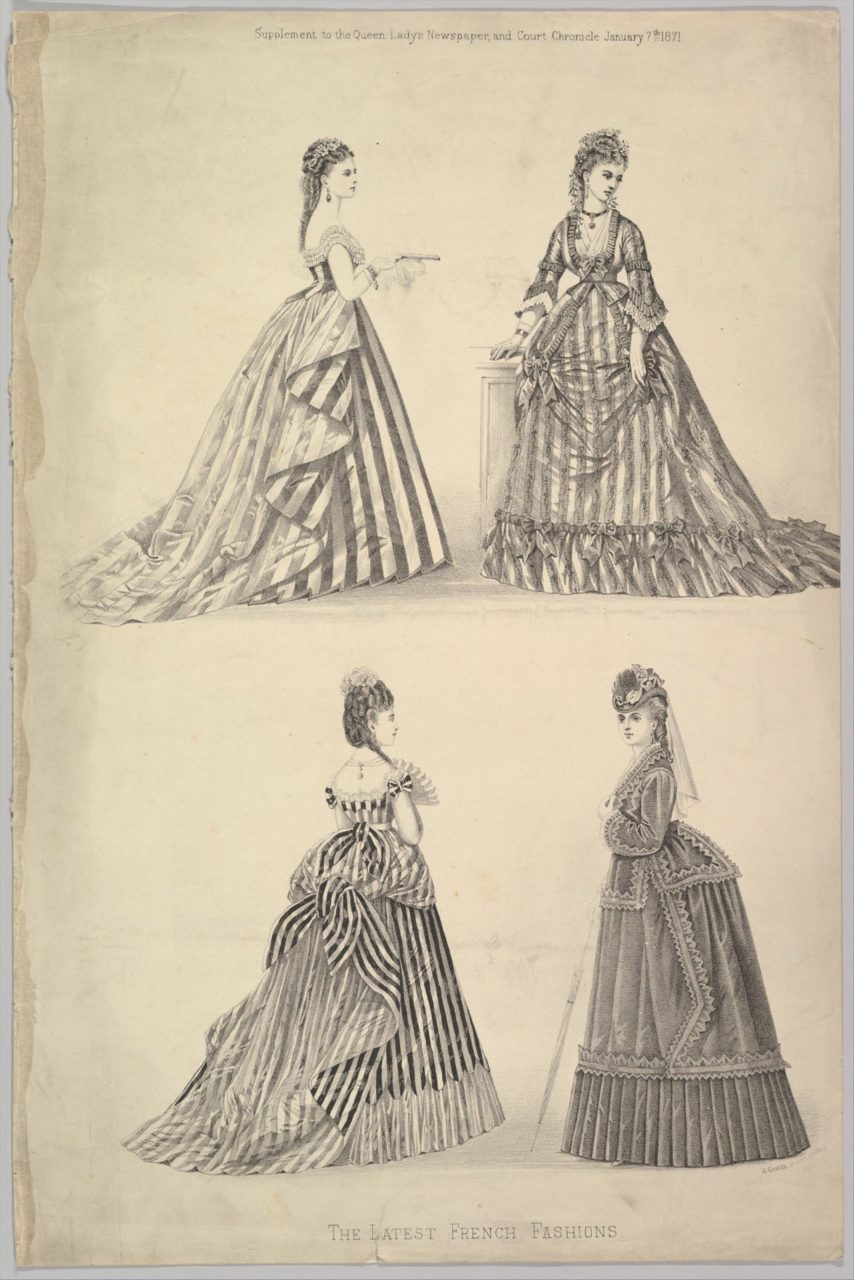

A directly comparable color fashion plate has not yet been found, but, as Ribeiro explains, such publications “relied on high-quality coloured plates,” hence black and white striped dresses were rare (47). One surviving black and white fashion plate is from The Lady’s Newspaper and Court Chronicle (Fig. 7) displays a very similar dress to the one that Nini wears in La Loge.

However, there were definitely a myriad of fashion plates depicting boldly striped dresses in similar evening styles such as a fashion plate from La Gazette rose‘s May 1874 issue that shows a boldly striped purple dinner dress (Fig. 8). The fashionability of striped dresses is mentioned in an April 1874 issue of Godey’s Lady Book and Magazine, stating that “broad stripes from one to two inches promise to be most fashionable” (389). Aileen Ribeiro also mentions its fashionability in her essay “The Art of Dress: Fashion in Renoir’s La Loge“:

“Nothing could be more à la mode than the dress worn by Edmond’s companion, Renoir’s model Nini Lopez, for striped outfits were all the rage in the early and mid 1870s, as fashion journalism indicated. In 1874, for example, we find La Mode Illustrée (April) describing the preponderance of striped toilettes, and the Journal des Modes (July) declaring that ‘black and white is always pretty, and will always be admired.'” (47)

The combination of full sleeves with ample décolletage makes the dress a bit of a strange fit for the opera, as Aileen Ribeiro explains:

“On first nights in particular, and in a box at the Opéra, dress was very formal – a low-cut dress, either sleeveless or with minimal sleeves, and elaborately dressed hair; piled high and decorated with jewels, flowers, ribbons and lace.

On less formal occasions at the theatre, women in boxes wore toilettes de soirées, with modest décolletage and sleeves usually to the elbow.” (54)

In the portrait, Nini wears several strings of pearls wrapped around her neck, wrapped especially tightly almost like a choker, and also has flowers pinned in her hair and at the center of the neckline of her dress, drawing attention to her décolletage. The pearls are “an unexpected touch, as simpler jewellery was more usual with a demi-toilette” (Ribeiro 60). Nini also wears white gloves that go past her wrist and a gold bracelet. In her right hand are a pair of opera glasses and she has a black and white lace fan resting in her lap.

Some surviving garments include and cream dinner dress from Mon. Vignon (Fig. 9) that features striking black bows and a white rose at the center of the neckline much like Nini’s real flowers, and a more casual silk white and light blue dress (Fig. 10).

The gentleman in the painting wears a typical outfit for men during that time period, as mentioned by Ribeiro in her essay from Renoir at the Theatre: Looking at la Loge:

“Formal evening dress for men – an English importation, like much menswear – consisted of a black coat and trousers, a white waistcoat (gilet) cut very low and wide so as to reveal a white shirt with a stiffened front; a starched white cravat completed the costume.

This is the tenue de première – evening dress as worn for the first night of a play, and for every performance at the elite theatres and the Opéra. In La Loge Renoir draws our attention to the starched expanse of the bluish-white plain shirt-front and the gold-cuff-links in the cuff as the man – the artist’s brother Edmond – raises his gloved hand to view the audience with his opera glasses.” (46)

However, the gentleman is not as typical as he might appear at first glance, as Ribeiro notes. His hair is a bit longer than most men kept it at the time, which suggests that he is artistic and bohemian, but his faint mustache and beard go to show how he is a stylish for the period (Ribeiro 47).

This artwork was created only a few years after the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71) and France’s defeat was sometimes blamed on “an excessive pursuit of pleasure during the Second Empire, and specifically the prominence of the demi-mondaine class who promoted extravagant styles of dress” (Ribeiro 49). However, Ribeiro explains how society changed its mind regarding this notion:

“The notion (dating back to classical times) that luxury corrupted public morality was countered during the Second Empire with claims that the luxury industries (most obviously fashion and fashion accessories) were not only crucial to the French economy but were democratically available to all with money, an essential part of the national character.” (49)

With renewed importance and the rise in popularity and significance of the theatre scene, the latest fashions were often displayed both on the stage and in what the attendees were wearing (Ribeiro 53), and is shown through what Nini is wearing in La Loge.

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown (British). The Latest French Fashions from The Queen, The Lady's Newspaper and Court Chronicle, January 7, 1871. Lithograph; 42.7 x 28.4 cm (16 13/16 x 11 3/16 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 63.608.6. The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1963. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 8 - Artist unknown. La Gazette Rose, May 1st, 1874. Fashion plate. New York: FIT Special Collections. Source: FIT Juliana Bui

Fig. 9 - Mon. Vignon (French). Dinner dress, 1875–78. Silk, glass. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.69.14.12a, b. Gift of Mary Pierrepont Beckwith, 1969. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown. Dress, 1874. Source: Pinterest

Diagram of referenced dress features.

Source: Author

Its Legacy

Renoir’s La Loge was part of a trend of paintings set in theater boxes among the Impressionists, with other views of loges painted by Mary Cassatt (Fig. 11) and Eva Gonzalès (Fig. 12) to name a few. These paintings show, as House argues, “how the theatre box could be viewed as a quintessentially modern subject” and “the theatre box represented modernity in microcosm” (House 41).

Fig. 11 - Mary Cassatt (American, 1844-1926). In the Loge, 1878. Oil on canvas; 81.28 x 66.04 cm (32 x 26 in). Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 10.35. The Hayden Collection—Charles Henry Hayden Fund. Source: Museum of Fine Arts

Fig. 12 - Eva Gonzalès (French, 1849-1883). A Box at the Theatre des Italiens, 1874. Oil on canvas; 98 x 130 cm. Paris: Musée d'Orsay, RF 2643. Gift of Jean Guérard, 1927. Source: Musée d'Orsay

References:

- Distel, Anne. “Catalogue of the Exhibition.” In Renoir, 203. London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1985. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/810262356.

- ———. “Renoir,(Pierre-)Auguste | Grove Art.” Accessed May 6, 2018. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000071492.

- “Fashions.” Godey’s Lady Book and Magazine 88 (April 1874): 389. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=inu.30000108702816;view=1up;seq=369.

- Groom, Gloria. “The Social Network of Fashion.” In Impressionism, Fashion, & Modernity, 38–39. Chicago: The Art Insitute of Chicago, n.d. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/843185621.

- House, John. “Modernity in Microcosm: Renoir’s Loges in Context.” In Renoir at the Theatre: Looking at La Loge, 27. 30, 32–34, 41. London: Courtauld Gallery, 2008. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/603113948.

- House, John, Ernest Vegelin van Claerbergen, and Barnaby Wright. Renoir at the Theatre: Looking at La Loge. London: Courtauld Gallery, 2008. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/603113948.

- Ireson, Nancy. “The Luxe of the Loge.” In Renoir at the Theatre: Looking at La Loge, 11. London: Courtauld Gallery, 2008. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/603113948.

- “Online Learning Resources – La Loge in Detail.” The Courtauld Institute of Art, n.d. https://courtauld.ac.uk/learn/schools-colleges-universities/learning-resources/online-learning-resources-renoir-at-the-theatre-looking-at-la-loge/online-learning-resources-la-loge-in-detail.

- “Renoir at the Theatre: Looking at La Loge.” The Courtauld Institute of Art. Accessed May 6, 2018. https://courtauld.ac.uk/gallery/what-on/exhibitions-displays/archive/renoir-at-the-theatre-looking-at-la-loge.

- Ribeiro, Aileen. “The Art of Dress: Fashion in Renoir’s La Loge.” In Renoir at the Theatre: Looking at La Loge, 46–47, 49, 53–54, 60. London: Courtauld Gallery, 2008. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/603113948.