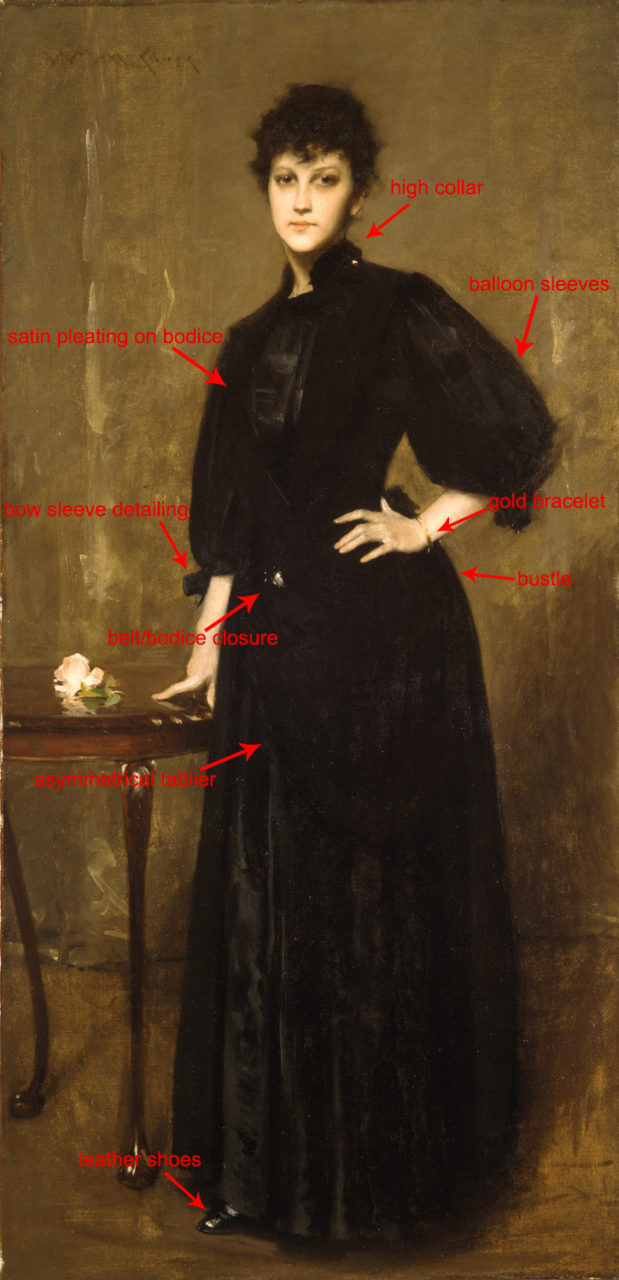

William Merritt Chase captures the style and youth of his art student, Mariette Benedict Cotton, in this portrait. She wears a black day dress made in the traditional bustle silhouette of the period with puffed sleeves that were rising in popularity at the time. Chase’s use of light adds depth to the piece, emphasizing folds in the fabric and the glittering of Cotton’s eyes and jewelry.

About the Portrait

W

illiam Merritt Chase (1849-1916) was one of the most well-revered American portraitists and landscape painters during the late 19th to early 20th century (Fig. 1). Lady in Black is a portrait that was not commissioned, but rather was painted when Chase was struck by inspiration. When its subject, Mariette Benedict Cotton, entered his studio as an art student, Chase saw her as a muse and asked her to model for this piece as well as Portrait of a Lady in Pink (Fig. 2) (Pisano 50). Lady in Black is a life-size portrait that depicts its subject in a black dress, standing in a room that is void of any objects save for a wooden table with a rose atop it. She stares unflinchingly out at the viewer, with one hand on her hip and the other gently resting on the table. Critically, the painting was received very well, winning a silver medal at the Paris Salon of 1891 and receiving great praise from viewers and critics alike. Chase himself also considered Lady in Black to be among his finest artworks, as he explained its inspiration in an article titled “How I Painted my Greatest Picture”:

“It takes years of hard work–but something more; it takes inspiration to produce a masterpiece.

One morning a young lady came into my Tenth Street studio, just as I was leaving for an art class in Brooklyn. She came as a pupil, but the moment she appeared before me I saw her only as a splendid model. Half way to the elevated station I stopped, hastened back, and overtook her. She consented to sit for me; and I painted that day, without an interruption, till late in the evening. The result is the ‘Lady in Black’ now hung in the Metropolitan Museum.

Such a model is a treasure find. It is the personality that inspires, and which you depict upon the canvas.” (967)

Fig. 1 - William Merritt Chase (American, 1849-1916). Self Portrait, 1914. Oil on canvas; 61 × 50.8 cm (24 × 20 in). Detroit: Detroit Institute of the Arts, 16.16. Gift of the artist. Source: Detroit Institute of the Arts

Fig. 2 - William Merritt Chase (American, 1849-1916). Portrait of a Lady in Pink, 1888-89. Oil on canvas; 178.4 x 102.2 cm (70.25 x 40.25 in). Providence: RISD Museum, 94.010. Gift of Isaac C. Bates. Source: RISD Museum

William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916). Lady in Black, 1888. Oil on canvas; 188.6 x 92.2 cm (74.25 x 36.3125 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 91.11. Gift of William Merritt Chase, 1891. Source: The Met

About the Fashion

O

ne of William Merritt Chase’s specialties was painting portraits of young, beautiful women. Lady in Black belongs to that genre and the visual appeal and fashionability of the portrait was praised by both viewers and critics alike.

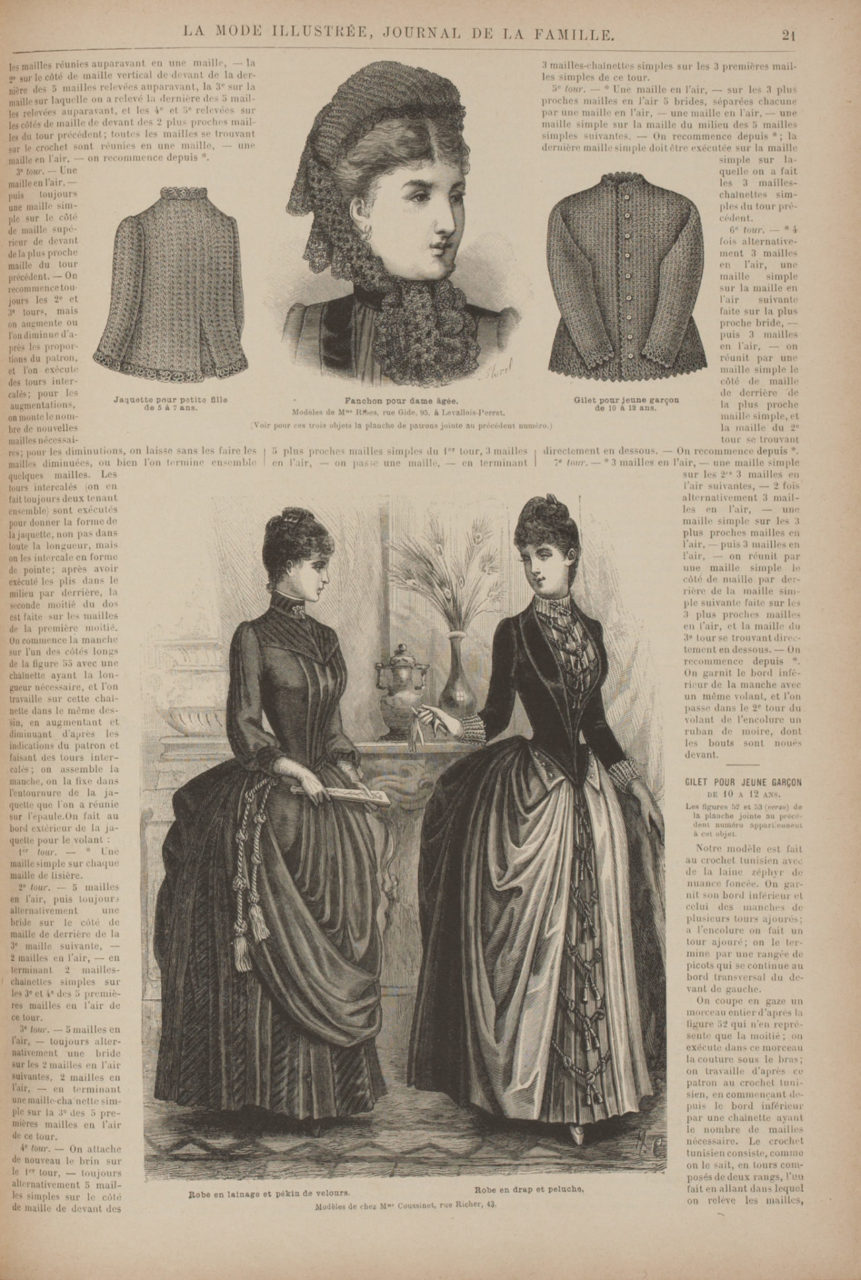

In Lady in Black, Mariette Benedict Cotton is wearing a day dress that showcases many of the popular fashions of the time. It has a prominent bustle, which can be seen on a slight angle behind her. Along with a tight-fitting bodice, this was an considered to be an incredibly stylish silhouette in the 1880s and early 90s. As shown in an 1888 La Mode illustrée fashion plate (Fig. 3), great emphasis was placed on the large amounts of fabric draped around the skirt and bustle. In Nineteenth-Century Women’s Fashion, Felicity J. Warnes comments upon this in her description of the 1880s:

“The principle feature of this decade was the return of the bustle, with its distinctive shape… it also attained larger dimensions than ever before, reaching its maximum size around 1888. The corset-like bodice now encased the whole torso, was closely moulded to the waist and bust and was flat over the hips. This gave the body a smooth and elegant shape, with a well-defined waist and pronounced curves.” (211)

The three-quarter length sleeves are quite voluminous and balloon out around the arms, cinching at the cuffs with bow detailing. These types of sleeves were rising in popularity at the time and are seen quite often in the late 1880s leading into the 1890s. In figure 4, the young girls on either side of this carte-de-visite photograph are wearing identical dresses that are similar to that of Mariette Benedict Cotton. The mean features of these garments are the puffed, three-quarter sleeves that echo those seen in Lady in Black.

The dress has a high collar, which was typical of ladies’ garments, and pleating detail at the front of the bodice. An asymmetrical swath of fabric, or “tablier”, drapes across the skirt, accentuating the subject’s figure. As seen in figure 5, a dress of red silk features similar styles of drapery, bodice treatment, and sleeve detailing to those seen in Lady in Black. The garment in the portrait is made of silk faille and silk satin, two fabrics considered to be quite fashionable at the time, which Chase has differentiated between by painting areas of black that look dull and others that seem to have a sheen. As advertised in a December 1888 Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine article:

“The most acceptable present a man can give to his wife or daughter is a dress of handsome, splendid wearing family black silk.” (510)

In Lady in Black, the subject is adorned with a few accessories that stand out on the predominantly black and brown color palette of the painting. She wears a thin gold bracelet and what appears to be a silver belt buckle or closure of sorts in the center-front of her dress. One black, patent leather shoe peeks out from beneath the dress. On the table rests a pink rose and, along with the accessories, these details clarify the fact that the black shade of this dress does not indicate mourning, but rather is a fashion choice.

As noted in many fashion magazines at the time, black was considered to be the most stylish clothing color for many years. Chase’s skillful rendering of multiple different types black silks layered over each other enforces the fashionability of the subject. As stated in the “Dress Conceits and Accessories” in the October 1888 issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine:

“Silk goods of all kinds are more sought after than they have been in years. Black is the prominent color in Faille Français, Venetian armures, Mascottes, Fleur de Soie and black silk is the fabric for general wear.” (321)

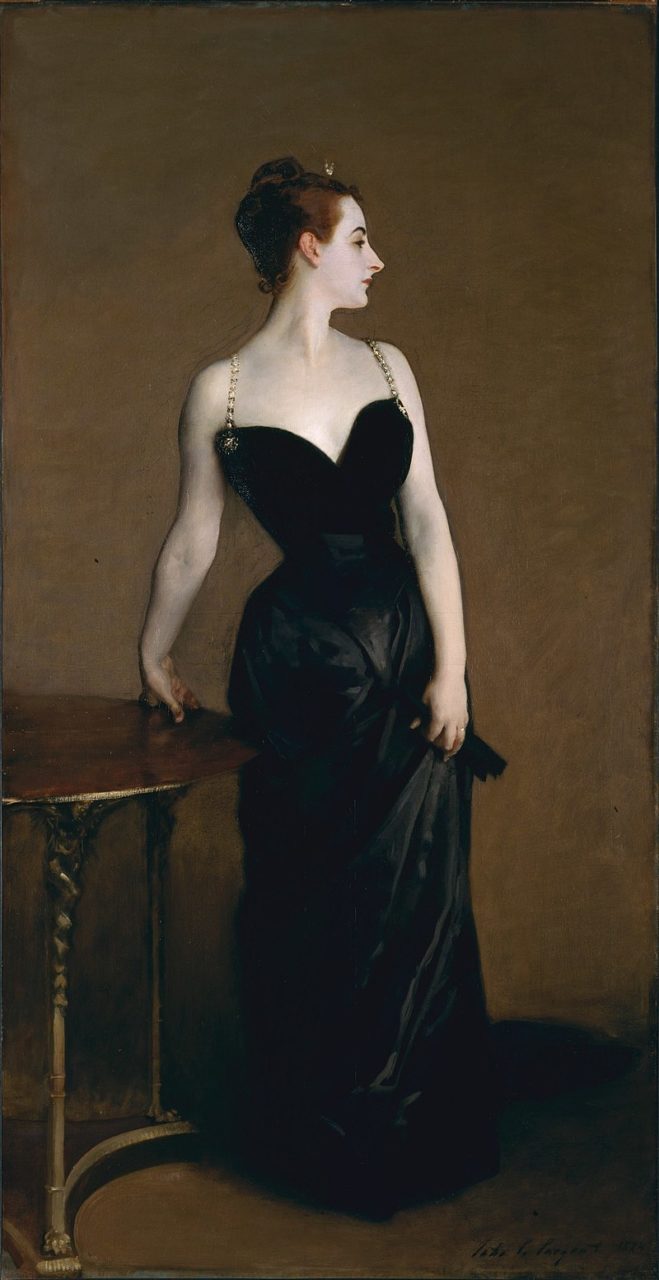

The composition of Lady in Black very closely resembles that of John Singer Sargent’s well-known portrait, Madame X (Fig. 6). However, although these two paintings have stylistic similarities, the garments displayed in each differ greatly. The evening gown worn by Sargent’s model, Virginie Gautreau, is quite daring while the day dress in Lady in Black was deemed much more acceptable. Carolus-Duran’s 1884 Portrait of Lucy Lee Robbins portrays a woman in a similar dress to that worn by Cotton (Fig. 7). She is dressed in black silk, with voluminous sleeves and a bustled silhouette. Even the accessories reflect those in Lady in Black, as she holds a pink rose and wears similar black shoes and a gold bracelet.

Carolus-Duran’s 1889 portrait of his daughter (Fig. 8) perhaps most closely resembles Cotton in her dress and youthful demeanor. The monochrome look also was favored by genre painters like Alfred Stevens (Fig. 9). Such paintings afforded the painter to demonstrate his mastery of painting in black, as well as his ability to capture the latest fashions of the day.

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown (French). La Mode illustrée; Wool and Velvet dress, January 13, 1888. Etching. Source: Bunka Gakuen Library

Fig. 4 - Brown & Draycott (British). Cabinet Photograph, April 1, 1888. Carte-de-visite photograph; 11 x 16 cm (4.33 x 6.3 in). Manchester: Manchester Art Gallery, 2008.40.6.1533. Source: Manchester Art Gallery

Fig. 5 - Designer unknown. Red Silk dress, 1889-82. Silk. St. Paul: Goldstein Museum of Design, 1965.005.007. Gift of Helen Ludwig. Source: Goldstein Museum of Design

Fig. 6 - John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925). Madame X, 1883-84. Oil on canvas; 208.6 x 109.9 cm (82.125 x 43.25 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 16.53. Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fund, 1916. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 7 - Charles Auguste Émile Carolus-Duran (French, 1837-1917). Portrait of Lucy Lee Robbins, 1884. Oil on canvas. Private Collection. Source: WikiArt

Fig. 8 - Charles Auguste Émile Carolus-Duran (French, 1837-1917). Portrait of Marie-Ann Faydeau, née Carolus-Duran, 1889. Oil on canvas; 61.4 x 50.5 cm (24.17 x 19.88 in). Lille: Palais des Beaux Arts de Lille. Source: The Athenaeum

Fig. 9 - Alfred Stevens (Belgian, 1823-1906). Afternoon by the Sea, 1885. Oil on panel; 31.1 x 21.9 cm (12 x 8.625 in). New York: Christie's. Source: Christie's

References:

- Chase, William Merritt. “How I Painted My Greatest Picture.” The Delineator 72, no. 6 (1908): 967–69. https://books.google.com/books?id=1QISx_sthusC&pg=PA967#v=onepage&q&f=false

- “Chase, William Merritt | Benezit Dictionary of Artists.” Accessed May 6, 2018. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/view/10.1093/benz/9780199773787.001.0001/acref-9780199773787-e-00036158.

- “Dress Conceits and Accessories.” Godey’s Lady Book and Magazine 117 (October 1888): 321. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433104870104;view=1up;seq=381.

- Pisano, Ronald G. William Merritt Chase. New York: Watson-Guptill, 1986. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/15020705.

- Pisano, Ronald G, Carolyn K Lane, and D. Frederick Baker. William Merritt Chase: Portraits in Oil. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/80331798.

- “The Shopper.” Godey’s Lady Book and Magazine 117 (December 1888): 510. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433104870104;view=1up;seq=596.

- Warnes, Felicity J. Nineteenth-Century Women’s Fashions. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/927401895.

- “William Merritt Chase | Lady in Black.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed May 6, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/10470.