Raimundo Madrazo often played with historical dress and aesthetics in his paintings. Masqueraders offers a luxurious look at late 1870s fancy dress, and later paintings of the woman’s costume give insight into the change in fashion.

About the Artwork

He completed several portraits of women holding and wearing masks (Fig. 3), a consistent motif in his work. However, he was also known for suggestive, playful genre paintings, of which he did many (Fig. 2) (Brettell 54).

Fig. 1 - Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta (1841 - 1920) (Spanish, 1841 - 1920). Self-portrait, 1901. Oil on canvas; 81.6 x 62.5 cm (32 1/8 x 24 5/8 in). Dallas, TX: Meadows Museum, Southern Methodist University, MM.73.01. Algur H. Meadows Collection. Source: Meadows Museum

Fig. 2 - Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta (Spanish, 1841-1920). Flirtation, ca. 1880. Oil on canvas; 70 x 121 cm (27 9/16 x 47 5/8 in). Los Angeles: Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, 66,150. Source: Lucas Museum

Fig. 3 - Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta (Spanish, 1841-1920). "Preparing for the Costume Ball", ca. 1880. Oil on panel; 58.4 x 40.9 cm (23 x 16.1 in). Private collection. Source: Wikimedia Commons

His father, Federico, was also a painter, and Madrazo’s early work complied with the family tradition of historic painting (Burón). Influenced by the Belgian artist Alfred Stevens, his brother-in-law Mariano José Bernardo Fortuny y Marsal, and the ambiance of Paris, Madrazo traded the dry academic scenes for the tableautin – the small and intimate genre paintings for which he is now well-known (Art Experts). He concentrated on this type of painting in his thirties and it became a high point in his career during which many of his paintings sold to American collectors for high prices (Burón).

The sitters in this portrait remain unidentified, though the woman appears in the same costume in a later painting called Pierrette (Fig. 4). They appear to be friends and are dressed in elaborate and beautiful costumes, quietly sharing drinks in a conservatory during or after a masquerade ball. The scene itself is fun and flirtatious, like so many of Madrazo’s artworks.

This painting was purchased by William Henry Vanderbilt in 1878, the year that Madrazo won the first-class medal at the Exhibition Universelle in Paris and was then elected into the French Academy (The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Fig. 4 - Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta (Spanish, 1841-1920). Pierette, 1878. Oil on canvas; 200 x 95 cm (78 3/4 x 37 1/2 in). Christie's, Lot 85, Sale 9494, Nineteenth Century European Art, New York, 18 October 2000. Source: Christie's

Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta (Spanish, 1841-1920). Masqueraders, 1875-78. Oil on canvas. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975.1.233. Robert Lehman Collection, 1975. Source: MMA.

About the Fashion

The clothing shown in this portrait is not an example of high fashion for the time the painting was done. Since these two were attending a masquerade ball, all guests were dressed in costume. Masquerade clothing, or ‘fancy dress’, from this period was often representative of animals, objects, and themes from nature, including astronomical phenomena and plants. It also commonly looked to the past for inspiration, resulting in costumes drawn from previous eras or from fairy tales. Costumes for these balls, attended by the wealthiest portion of society, were elaborate and decadent.

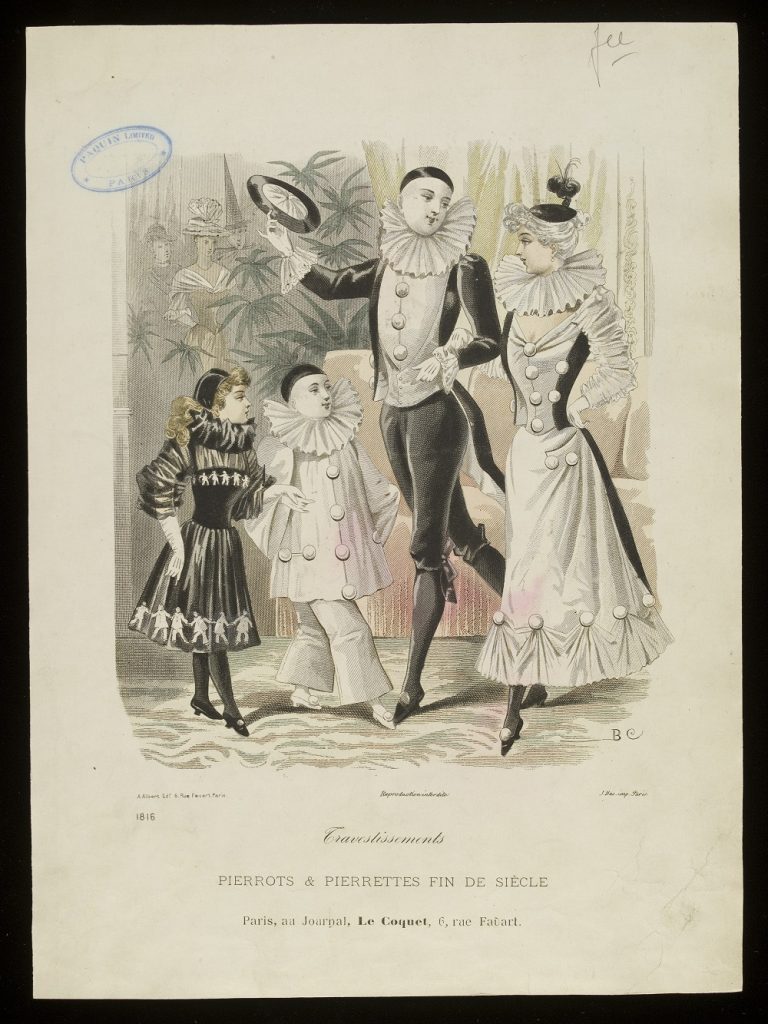

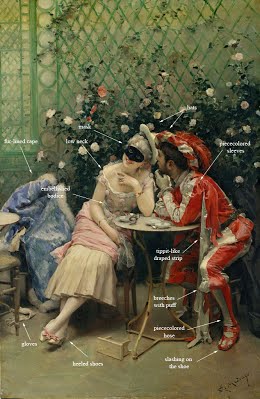

Fancy dress does follow the line of stylish dress, if not the aesthetic. The woman’s dress is inspired by the 16th-18th century Commedia dell’arte Pierrot character, which was a popular choice for costume (Fig. 5). Her outfit is made in a very fashionable cut for a late 1870s gown; compare it to the evening dress in figure 6, though the masquerade dress is much shorter–a defiance of norms acceptable in fancy dress.

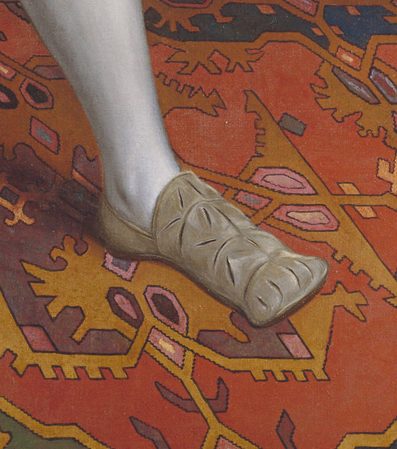

The woman’s cape and shoes are clearly inspired by Madrazo’s love of Rococo style. Lavish satin opera capes were worn by women in this period (Fig. 7) but hers appears to have less structure, and in cut resembles an 18th-century mantle or pelisse (Fig. 8). The vibrant blue lining, visible in Figure 4 above, is a very Victorian element, however. Her shoes, while in the late Victorian style (Fig. 9), have a toe and heel shape that also resembles late 18th century shoes (Fig. 10). Madrazo had a fondness for dabbling in other centuries, and it is apparent in her accessories.

Fig. 5 - C. B. (British). Pierrots & Pierrettes, Fin de Siécle, 1890s. Hand-coloured lithograph. London: The Victoria and Albert Museum, E.22397:67-1957. Source: VAM

Fig. 6 - Pierre-Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919). Portrait of the Actress Jeanne Samary, 1878. Oil on canvas; 174 x 105 cm. St. Petersburg: The State Hermitage Museum, ГЭ-9003. Source: The Hermitage

Fig. 7 - Emile Pingat (French, active 1860–96). Opera cloak, 1882. Silk, fur, feathers, metal. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.60.42.13. Source: MMA

Fig. 8 - Claude-Louis Desrais (French, 1746–1816). Gallerie des Modes et Costumes Français, 1778. Hand-colored engraving on laid paper. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 44.1362. Source: MFA

Fig. 9 - Peter Yapp (British). Pair of Wedding Shoes, 1885. Satin. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.428C-1990. Given by the Hon. Mrs S. F. Tyser. Source: VAM

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown (English). Indoor buckle shoe with buckle, ca. 1760-1769. Silk satin, leather, silver; height 13cm, width 7. Ultimo, NSW: Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, H4448-53. Source: MAAS

The man’s dress is a combination of traditional 15th and 16th century German clothing (Fig. 11), streamlined to appear more fashionable in a 19th century style.

He has on ‘particolored’ clothing: garments with panels of contrasting fabric, a trend that originated in the Middle Ages to help identify a man by his family colors. His costume consists of a doublet, a hat, breeches, striped hose, shoes, a belt, and gloves.

Historical comparisons can be made with his wardrobe. His belt is anachronistic for the 16th century, as clothes still tied together at that time. His shoes have the straps and wide slashes of 16th century “cow mouth” or “duck bill” shoes (Fig. 12), but they have the slimmer, narrower look of a late Victorian men’s shoe (Fig. 13). His hanging sleeves also add a 15th-century touch to what is otherwise mostly a 16th century outfit, and the wide, puffed legs of the breeches in figure 11 are slimmed down and cut closer to his thighs to be more attractive to the Victorian eye.

Fig. 11 - Artist unknown (German). Detail from the Códice de Trajes, p. 42, 1546-7. Laid paper; 20 x 20 cm. Madrid: National Library of Spain, Res/285. Source: Biblioteca Digital Hispánica

Fig. 12 - English School (after Holbein). Detail from the Ditchley Portrait of Henry VIII, 1600-1610 (original 1536/7). Oil on canvas. Private collection (Previously the Weiss Gallery, London). Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 13 - Thomas of St. James' Street (British). Pair of boots, 1890-1900. Cloth and patent leather, with pearl buttons, machine and hand-sewn. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.6&A-1970. Source: VAM

“Pierrette” wears a fitted evening bodice with a low, wide neckline and off-the-shoulder sleeves. It is cream-colored and decorated with pale pink, round pom-poms. The skirts are wide-hipped but slim, and consist of a ruched pink silk apron overskirt that gives way to a fuller cream-colored underskirt that ends at mid-calf. She has a fur-lined cape draped over a chair that is more visible in Pierrette (Fig. 4). Her accessories are white stockings, cream-colored slippers with dainty pink ribbons, a cone-shaped hat with a small brim, a black mask, and gold jewelry.

Madrazo painted two additional portraits of his “Pierrette”; one in 1878 (Fig. 4) and another much later in 1893 (Fig. 14). The costume is generally the same in all three paintings, but makes a useful comparison for how fashion changes over time – and how artists concede to the mode. What was earlier a ruched overskirt and pleated underskirt in late 1870s fashion are now smooth, gored expanses of satin in 1890s fashion. Her hair is now frizzed into curly bangs, and her shoes have also changed – they are now late Victorian heels, and she has cast her 18th century mules aside on the floor next to her.

One key accessory in Masqueraders is the woman’s mask, called a moretta. Masks were an extremely popular accessory for costume balls like this (Fig. 15), and they originated in Venice in the 15th century. Venetians were permitted to wear masks in-between Christian holidays, and celebrated the ideas of disguise, mystery, and concealed identity intertwined with everyday life (Buchart). Gloves, jewelry, and elaborate headpieces that coordinated with the costumes were also common accessories.

The garments in this painting were most likely custom-made and sewn by hand. Such costumes were to be worn at brilliant parties that celebrated decadence and indulgence and complied to an extravagant theme (Fig. 16). These parties often strayed as far as possible from reality, allowing not only women but also men to abandon their customary dress and exchange it for something grand and otherworldly. It was in this capacity that couture houses first made clothing for men. These men often commissioned their costumes from their wives’ and lovers’ couturiers (De La Haye 111-117).

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert shared a love for fancy dress, which helped it grow in popularity in England in the nineteenth century. In France, Empress Eugènie also enjoyed masquerade balls. An emphasis on private parties instead of large public affairs developed, and fancy dress now also encompassed the use of historical costume, mainly medieval royalty. This stemmed from widespread interest in revivalism and the trends of the past.

Since these costumes were so elaborate and luxurious, as well as made specifically for these kinds of parties, we can assume that the sitters were quite wealthy and of high social standing, though that was not always the case with party guests. Typically, anyone who could afford a ticket was allowed to go to the ball. These parties had strict rules about costume: they were required for entry and attendees must disguise their identity. The masks were usually removed after the dinner feast or after midnight. Until that time, however, identities were concealed, and thus prostitutes and gamblers could, in theory, happily mingle with the upper class. Since such costumes were specifically for these parties and not for everyday use, they could play around the usual rules of style: shorter hemlines and generally more revealing, outlandish silhouettes were not only accepted but enthusiastically embraced (Butchart).

Fig. 14 - Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta (Spanish, 1841-1920). La Toilette de Pierrette (Published in Le Figaro), 1893. Paper; 64.5 x 42 cm. Sweden: Kalmar Läns Museum, KLM 23970:58. Source: Digitalt Museum

Fig. 15 - Attr. Marco Marcola (Italian, 1740-1793). Arlecchino, Colombina and other Commedia dell'Arte characters, 1760s. Oil on canvas; 52 x 41.7 cm (20½ x 16½ in). Christie's, Lot 362, Sale 1273, New York, 30 September - 1 October 2003. Source: Christie's

Fig. 16 - Léon Sault for Maison Worth (French). Hell, 1860s. Watercolour and pencil drawing. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, E.22048-1957. Given by the House of Worth. Source: VAM

Diagram of referenced dress features.

Source: Author

Its Legacy

Masquerade balls originated in Venice in the 15th century and eventually spread throughout Europe (Butchart). Today, the idea of masquerade is still widely popular across the globe. It is a common theme in photoshoots, editorials, parties, and galas, and often appears in story lines of books, movies, plays, and television shows. Gerard Butler (Fig. 17) played the mysterious Phantom of the Opera (2004), which was set in the 1880s; during a masquerade scene, he donned an extravagant red costume reminiscent of the 1790s. The idea of disguise and mystery holds a certain enticing romance that has proved itself timeless.

Fig. 17 - Alexandra Byrne (British, 1962-present). Movie still from Andrew Lloyd Webber's The Phantom of The Opera featuring the "Red Death" masquerade costume, 2004. Red crushed velvet. Source: Soundcloud

References:

- Brettell, Richard R., Paul Hayes Tucker, and Natalie H. Lee. Nineteenth- and Twentieth-century Paintings. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/751459217

- Burón, Jesús Gutiérrez. “(4) Raimundo Madrazo De Garretta.” Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Accessed December 8, 2015. https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-9002296016?rskey=xfLexx

- Butchart, Amber. “In the Spotlight: An Unofficial History of Fancy Dress.” Amber Butchart Fashion Historian. October 26, 2012. Accessed December 8, 2015. https://amberbutchart.wordpress.com/2012/10/26/in-the-spotlight-an-unofficial-history-of-fancy-dress/

- Haye, Amy, and Valerie D. Mendes. “Fancy Dress.” In The House of Worth: Portrait of an Archive, 111-117. London: V&A Publishing, 2014. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/858843985

- “Masqueraders.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed December 8, 2015. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/459124

- “Raimundo De Madrazo Y Garreta (1841-1920).” Raimundo De Madrazo Y Garreta. Art Experts. Accessed December 8, 2015. https://www.artexpertswebsite.com/artist/madrazo-y-garreta-de/