El Jaleo is one of Sargent’s many paintings relating to Romani culture, and brings a vivid scene of Spanish dance, music, and fashion to the viewer.

About the Artwork

One critic wrote of El Jaleo in 1882, “The painting is slovenly and the drawing wretched,” after it was presented at the Schaus Gallery in New York, which had purchased the picture from the 1882 Paris Salon for 10,000 francs (“Mr. Sargent’s ‘El Jaleo,'” 286). Others have called it daring, risky, unconventional, dramatic, erotically off-center, or odd – but it remains one of artist John Singer Sargent’s acclaimed works. El Jaleo was painted in 1882 after time spent travelling through Spain, an experience that allowed him to produce works that not only exhibited new artistic abilities but also an improved understanding of rural life, culture, and class discrimination.

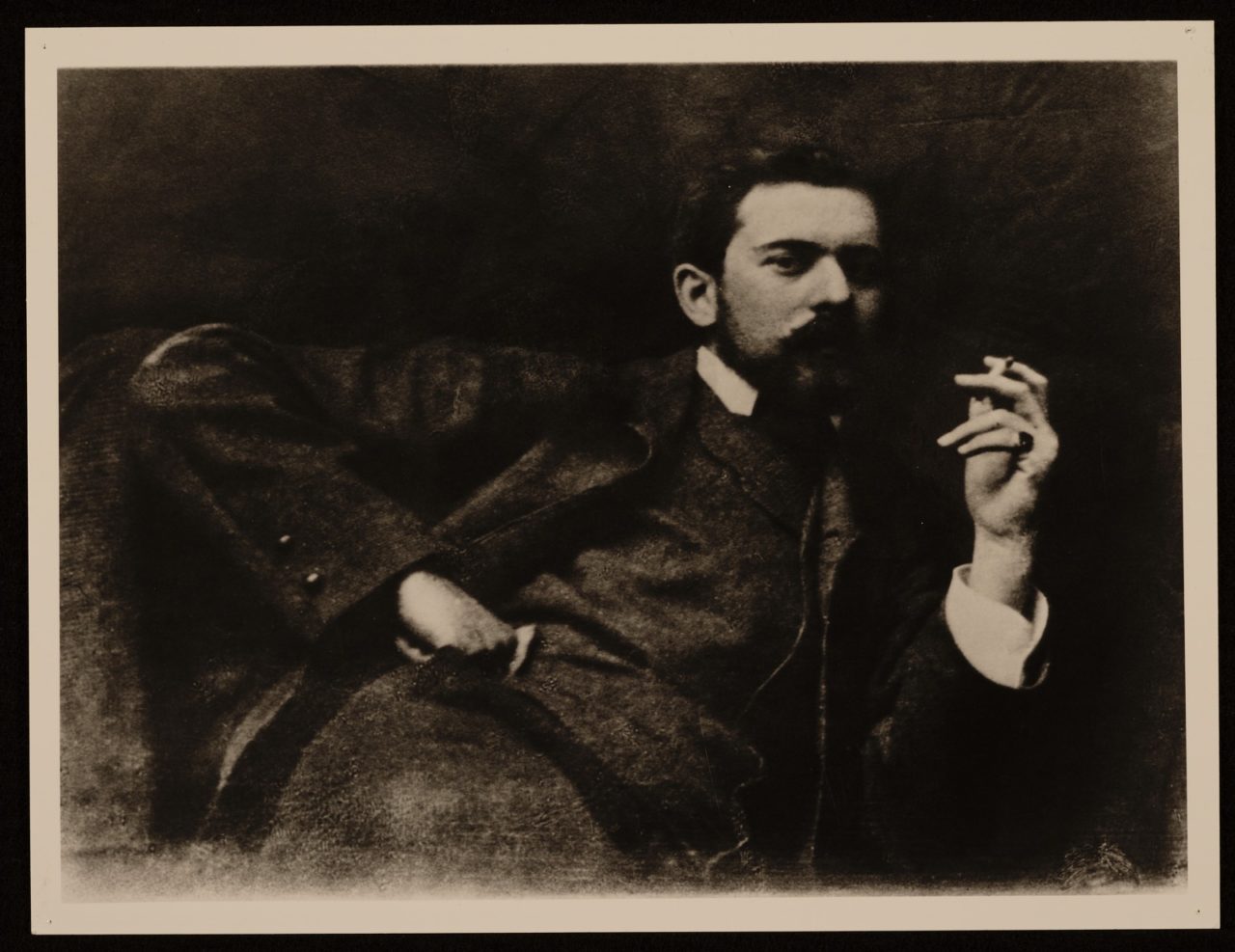

Sargent (Fig. 1) was born in in Florence in 1856 to American parents and raised as an expatriate. Early in his life, Sargent was exposed to the techniques of the French Impressionists, especially while studying in Paris in his late teens. He befriended Impressionist artists Claude Monet, Édouard Manet, and Paul Helleu (Fig. 2) and combined Impressionist flavors with his favored realism. He distinguished himself amongst the most talented and influential artists of the day while creating his own distinct artistic identity.

His perspectives on societal inequities were formed through the close observation of his subjects, many of whom were oppressed Romani (gitanos)** who inhabited regions of Spain, especially in and around Madrid. As described by author Trevor Fairbrother in his essay for Alan Chong’s Eye of the Beholder (2003):

“[These people] were believed to ignore ethical principles and exalted superstition over orthodox religion [and] endured oppression in numerous countries during the nineteenth century, but artists and bohemians idealized them as free spirits.” (159)

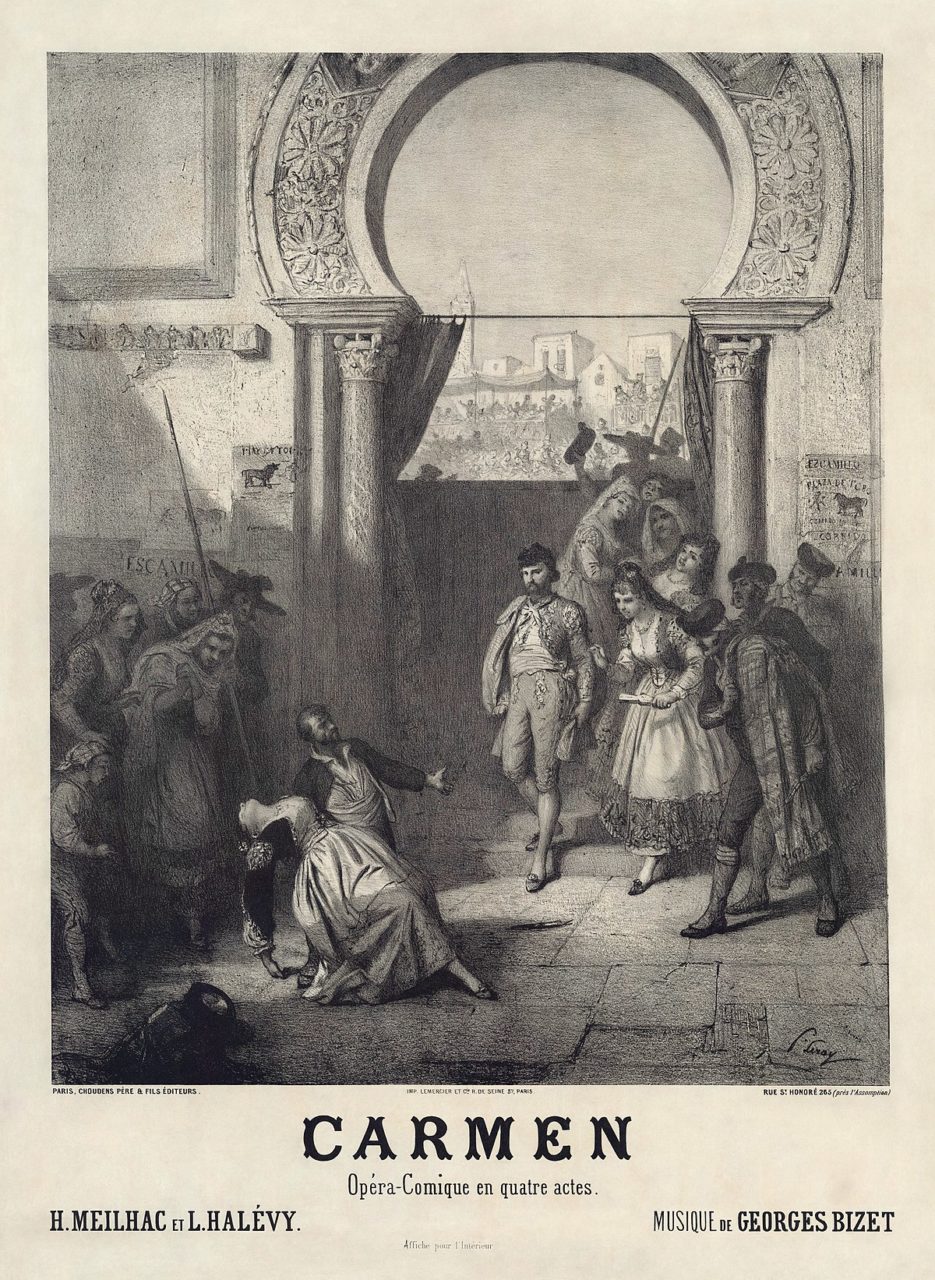

The scandalization of Romani culture was partially caused by the production of the famous opera Carmen, which opened in Paris in 1875 and told the story of a love triangle between a Roma woman, an army officer, and a bullfighter (Fig. 3). Sargent ignored the negative stereotypes but fed into the positive ones of the Romani as ‘free spirits’. While in many cases he portrayed the people he saw honestly, rather than in the ways that the upper class would agree with, he certainly idealizes his subjects.

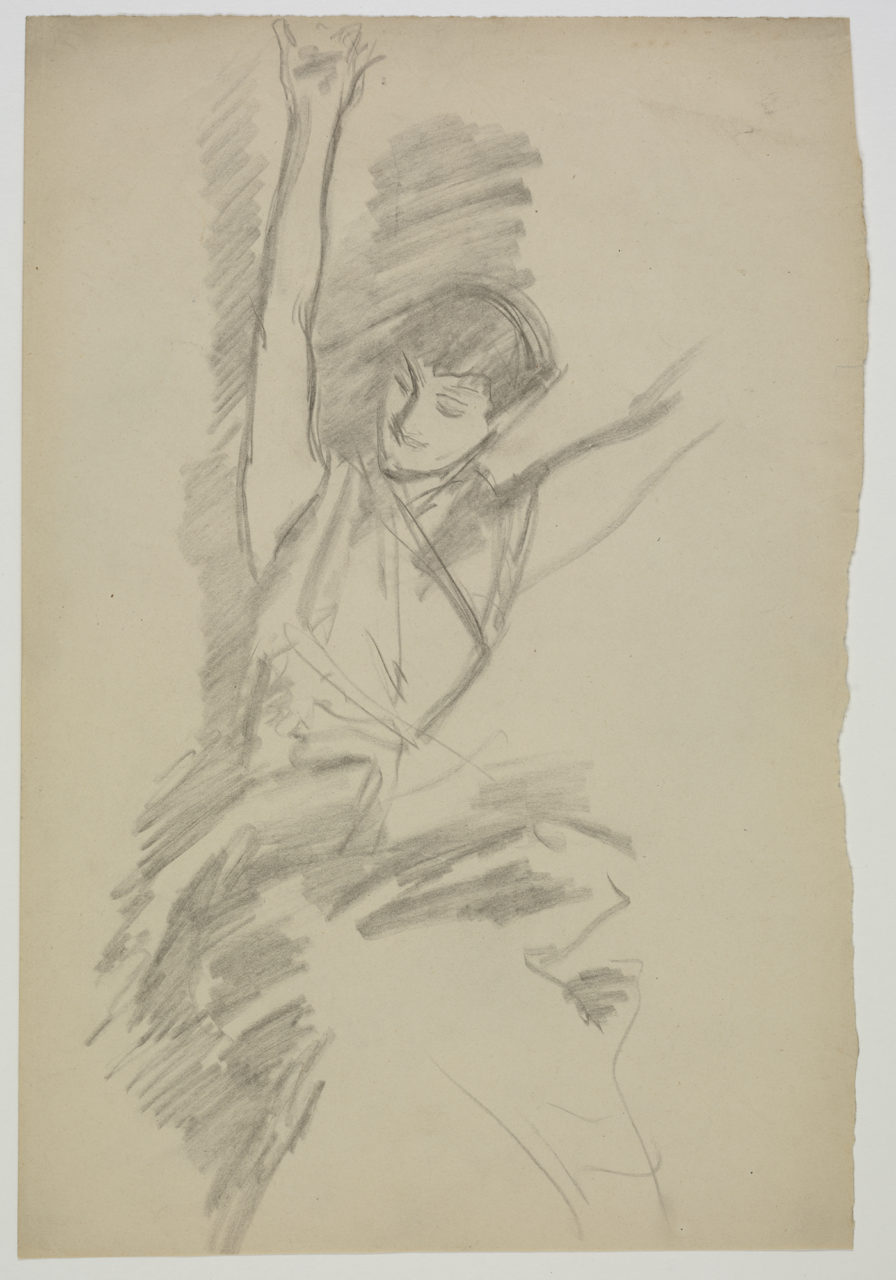

This can be seen in figures 4 and 5, which are examples of Sargent’s studies in preparation before he began the full painting of El Jaleo. The movement of the woman, so liberated and free though she is a mere spectator of the performance, shows an uninhibited energy and “free spiritedness” that Sargent understood the Romani to possess. The dramatic, expressive faces of the musicians, too, seem to illustrate the great overpowering feelings that traditional music would excite in those who played and listened to it. While these may seem to be kind, encouraging representations, any sort of idealization can still be harmful to the people it purports to represent, especially when created by an outsider – which Sargent was. These first sketches of Sargent’s memories are indicative of how affected he must have been by the the music, dancing and artistry of the Romani, and while misguided, they exhibit his respect for their existence as members of a society that did not value them.

The Isabella Stewart Gardner museum, which currently owns the painting, describes Sargent’s naming process:

“He named the painting El Jaleo to suggest the name of a dance, the jaleo de jerez, while counting on the broader meaning jaleo, which means ruckus or hubbub. The painting was exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1882 with the more explicit title El Jaleo: Danse des gitanes (Dance of the Gypsies).” (“El Jaleo,” ISGM) **

In the final version of El Jaleo, the scene is a dark, moody setting with guitars and figures lined up against the back wall, all of whom are participating in the music in some way. The sketch in figure 6 allows more details to be seen. Each face possesses a unique, compelling expression, and the shadows cast on their faces add an air of mystery. All of the figures exist in harmony, and their movements put together allow for an onlooker to imagine music being played passionately and rhythmically. The horizontality of the painting mimics a shallow stage space and brings the viewer closer. It has inspired many modern artists, but what did reviewers think of it at the time?

Theodore Child, who reviewed the painting in an article about “American Artists at the Paris Exhibition” for Harper’s in September 1889, claims that it “created a sensation, and induced enthusiastic critics to evoke the souvenir of [Francisco de] Goya” himself (504). Indeed, the mood of El Jaleo is similar to some of Goya’s most famous paintings (Fig. 7).

However, one particularly passionate critic in the appropriately-named periodical The Critic writes in an article titled “Mr. Sargent’s ‘El Jaleo'” in the October 21, 1882 issue that:

“‘El Jaleo’…is loud, almost coarse; slipshod in execution; fearfully and willfully wrong in drawing; weak in composition. It has nearly all the faults that a picture can have. Yet it has also some great merits… It is original. It is beautiful and approximately true to the effect intended in tone, in color, and in light.

Still, the very rashness of the attempt makes the picture interesting; and after looking at it for a while, one begins in spite of oneself to enjoy the novel and exquisite range of grays and flesh-tints, and the subtle appreciation and values and of certain curiosities of light and shade which, if nothing else, will yet gain Mr. Sargent a place among the modern masters of painting.” (286)

The painting’s technique was avant-garde for the time and Sargent’s rendering of the dancer’s clothes would prove equally controversial.

** The word “Gypsy” is now considered a racial slur, and uses of it in quotes in this article do not reflect the views of the Fashion History Timeline. We have used the correct terms – Romani or Roma – where possible.

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown. John Singer Sargent, ca. 1880. Photographic print; 17 x 22 cm. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Archives of American Art, 7991. Source: AAA

Fig. 2 - John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925). Paul Helleu, Between 1882-1885. Watercolor on paper; 23.5 x 37.3 cm (9 1/4 x 14 3/8 in). Private collection. Source: JSS

Fig. 3 - Prudent-Louis Leray (French, 1820-1879). Carmen, 1875. Lithograph; 79 x 60 cm. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France, FRBNF42297121. Source: Gallica

Fig. 4 - John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925). Study for El Jaleo: Seated Woman, 1881. Charcoal on paper; 34.6 x 23.5 cm. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, S.G.Sar.4.2.4.11. Source: Gardner Museum

Fig. 5 - John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925). Study for El Jaleo: Seated Musicians' Faces, 1881. Charcoal on paper; 23.7 x 33 cm. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, S.G.Sar.4.2.4.13. Source: Gardner Museum

Fig. 6 - John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925). Sketch After 'El Jaleo', 1882. Pen and ink on paper laid down on paper; 22.9 x 33 cm. Christie's, Sale 17034, American Art, New York, 22 May 2019. Source: Christie's

Fig. 7 - Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828). A scene from 'The Forcibly Bewitched', ca. 1798. Oil on canvas; 42.5 x 30.8 cm. London: The National Gallery of Art, NG1472. Source: Wikimedia Commons

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). El Jaleo, 1882. Oil on canvas; 232 x 348 cm. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Musuem, P7SI. Gift from Coolidge to Isabella Stewart Gardner, 1914. Source: Gardner Museum

About the Fashion

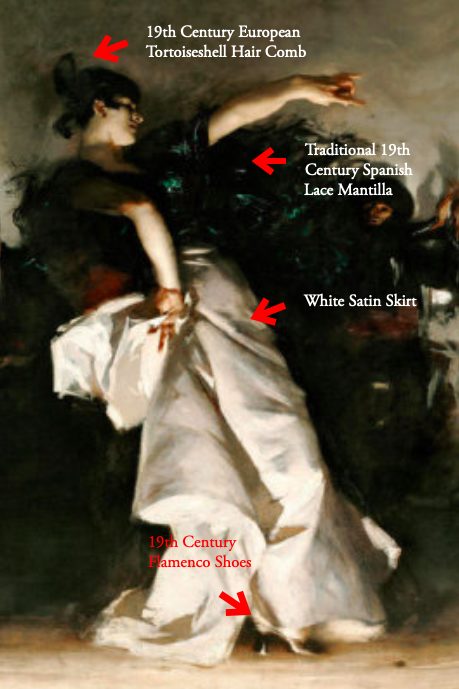

What is most highlighted in John Singer Sargent’s El Jaleo is the intricate, semi-traditional costume of the featured dancer. She wears a long, white satin skirt that is reflected in the light, along with a Spanish lace mantilla and hair comb. Although the elements may appear minimal at first glance, there is incredible detail and artistry that goes into the making of every piece, and each has a unique history.

Tortoiseshell combs (Fig. 8) like the one featured in the painting are described by the Smithsonian as:

“Ornate tortoiseshell combs called peinetas were brought to Spanish-held territories in the 18th century, and by the 19th century, they spread across Puerto Rico, Cuba, Mexico, Peru, Brazil and the southern-most region of South America. For centuries, tortoiseshell was a luxury material valued for its marbled appearance, translucency and durability.” (“Intricate Beauty”)

The peinetas were often used to hold up mantillas, traditional Spanish shawls often made of black lace. In the painting, the flamenco dancer can be seen with one draped around her shoulders, using the silk garment to accentuate her movements. The mantilla shown in figure 9 is probably similar to the one featured in El Jaleo.

Also shown in the painting is the skirt of the dancer’s pale pink satin dress, which creates “a more dramatic contrast between dark male clothes and light female dresses” and draws the brightest points of light to the bottom of the painting (Fairbrother 101). The contrasting effects of the skirt, which appears solid and thick, and mantilla, which appears light and airy, are due to the weave and construction of each garment. The mantilla would have been made of thin silk lace, more for decoration than warmth. The skirt appears to be made of silk satin, a fairly heavy fabric to begin with, and would have been flatlined in another fabric–perhaps polished cotton–and worn over multiple petticoats for the structured look. There was probably a matching satin bodice, and of course a corset underneath to help support the weight of the skirts and maintain shape underneath the bodice.

Many elements of the woman’s ensemble are true to the late 19th-century fashions of actresses, dancers and other performers who were widely regarded as celebrities and trendsetters. It is entirely possible, however, that Sargent made up the outfit. The painting in figure 10 features a famous Spanish actress and represents the way a wealthy Spanish woman would have dressed around 1880. Despite some similarities to the dancer in Jaleo, her ensemble includes ¾-length sleeves and a long train–suitable for a reception rather than wild dancing. Figure 11 is a photograph of a flamenco dancer in American performance costume, which bears almost no resemblance to anything traditional dancers wore in Spain (Fig. 12).

Fig. 8 - Designer unknown (American or European). Comb, 19th century. Tortoiseshell. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art,, C.I.47.73.1. Source: MMA

Fig. 9 - Designer unknown (European). Mantilla, Third quarter 19th century. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.2770. Source: MMA

Fig. 10 - Luis Taberner Montalvo (Spanish, 1844-1900). Portrait of María Álvarez Tubau, 1878. Oil on canvas; 212 x 137 cm. Almagro: Museo Nacional del Teatro, P00091. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 11 - Designer unknown. Carmencita, Flamenco Dancer, 1890s. Albumen print. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, ARC.007529. Source: Gardner Museum

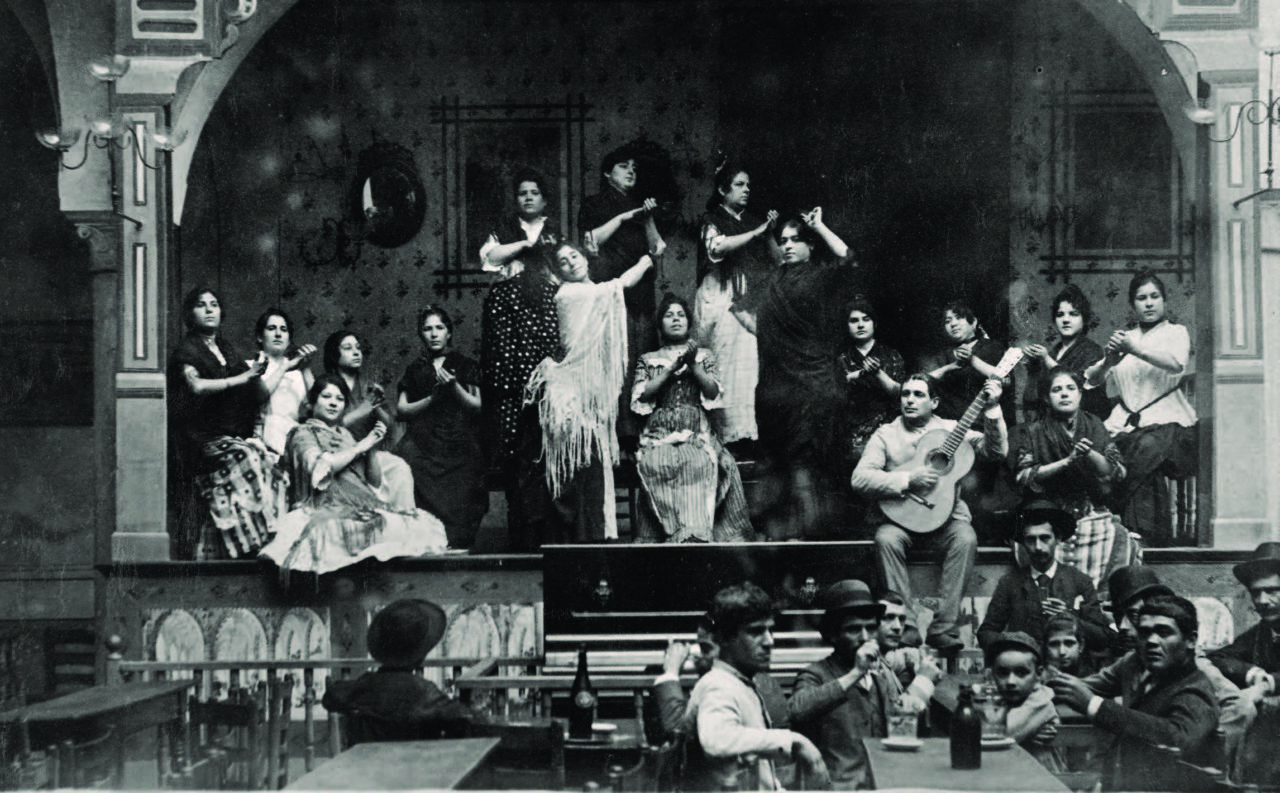

Fig. 12 - Emilio Beauchy (Spanish, 1847-1928). Traditional Cuadro on Stage in Sevilla, ca. 1880. New York: Hispanic Society of America. Courtesy of Hispanic Society of America, New York. Source: El Palacio

Dresses fashionable in the years 1878-1882 were often in the ‘princess line’ style, which fit closely to the body and ended with a narrow skirt (Fig. 13).

The writer of the aforementioned October 21, 1882 The Critic article describes the dancer unfavorably:

“The principal figure in the picture is a dancer, a coarse and hardened woman, posed in a most ungainly attitude, in the glare of the foot lights on the narrow stage of some cheap Spanish theater… The heavy silk skirt, of a pale pink, strongly lit up though disarranged, does not seem in motion… But the light shawl which she wears over her shoulder is, of course, in violent motion.” (286)

Perhaps Jaleo’s dancer is not attired and set in the formal atmosphere of María Àvarez Tubau’s expensive home, but what could give this critic the impression that this wild dancer is “coarse and hardened” and performs at a “cheap theater”? He is clearly biased; he looked at a painting and saw the absence of the refined settings that he enjoyed and decided to vent his frustration on the subject of the painting (and, as seen above, Sargent himself). The critic looked at this painting and saw Romani people, who he understood to be “coarse and hardened,” and ignored the beauty that Sargent put forth.

The only aspect of this dancer’s dress that might indicate she is anything less than proper is her sleeve length. Yet evening gowns for balls in this era were of the same cut (Fig. 14). Clearly, the author was stereotyping unfairly.

Fig. 13 - Designer unknown (Spanish). La Moda Elegante Ilustrada, June 1882. Fashion plate. vol. 41, no.1, p. 7. Source: Google Books

Fig. 14 - Charles Frederick Worth (British, 1825–1895). Evening dress, ca. 1882. Silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.635a, b. Source: MMA

Its Legacy

There is no doubt that John Singer Sargent’s El Jaleo had a lasting effect on all who observed his painting, allowing the general public to get a glimpse into the life of a people they had previously known very little about.

However, as Ninotchka Bennahum points out in Antonia Mercé, “La Argentina”: Flamenco and the Spanish Avant Garde (2014):

“El jaleo was an orientalized portrait of Spain… By 1900, both [El Jaleo and Carmen] had come to symbolize the same thing: the seductive Spanish Gypsy woman.” (Bennahum, 78)

While “their appeal was enduring,” both opera and painting joined in the wave of stereotypes and idealizations surrounding an oppressed minority (Bennahum 78). No matter how great Sargent’s love was for Andalusian music or the setting of Romani encampments (Fig. 16), we will never know the true thoughts and lives of the people whom he painted.

Sargent continued to paint dancers and country scenes in between his formal portraits for high-society women. There are clear parallels between El Jaleo and Sargent’s later works, especially in the way in which he paints the movements of the figures and how he illustrates the beauty of their garments (Fig. 17).

El Jaleo was given to Isabella Stewart Gardener in 1914, and today sits in the Spanish Cloister at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, Massachusetts (Fig. 18).

Fig. 18 - Photographer unknown. El Jaleo in the Spanish Cloister, n.d. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Source: Gardner Museum

Fig. 16 - John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925). The Spanish Dance, 1880. Oil on canvas; 89.5 × 84.5 cm. New York: The Hispanic Society of America, A152. Presented to the Hispanic Society by Archer M. Huntington, 1922.. Source: HML

Fig. 17 - John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925). La Carmencita Dancing, 1890. Oil on canvas; 137.2 x 88.9 cm (54 x 35 in). Private Collection. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

References:

- Bennahum, Ninotchka. Antonia Mercé, “La Argentina”: Flamenco and the Spanish Avant Garde. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2014. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1020498461

- Child, Theodore. “American Artists at the Paris Exhibition.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 79, no. 472 (September 1889). Accessed 11 June 2020. Google Books

- Chong, Alan, Richard Lingner, and Carl Zahn. Eye of the Beholder: Masterpieces from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Boston, Mass: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2003. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/901098923

- “El Jaleo.” The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Accessed May 6, 2020. https://www.gardnermuseum.org/experience/collection/13259#gref

- Fairbrother, Trevor J. John Singer Sargent. New York: Abrams, 1994. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/28333224

- “Intricate Beauty.” Smithsonian Snapshot. Smithsonian Institution, October 15, 2018. Accessed May 6, 2020. https://www.si.edu/newsdesk/snapshot/intricate-beauty

- “Mr. Sargent’s ‘El Jaleo.'” The Critic 47, 21 October 1882. Accessed 11 June 2020. Google Books