In this lively portrait of Carmencita, William Merritt Chase suggests the audience’s enthusiasm for her dancing by including a gold bracelet and flowers tossed at her feet. The celebrated dancer was painted by many other artists—usually wearing an extravagant dance costume—but none captured her exuberance quite like Chase did in this portrait.

About the Artwork

W

illiam Merritt Chase was an American artist who first discovered his interest in art while living in Indianapolis. In order to pursue these interests Chase began working under the wings of local artists such as Barton S. Hays and Jacob Cox, who urged Chase to continue his studies in Europe (Peltakian). However, his stay in Europe was short-lived as his money began to dwindle. Chase decided to move back to the United States to take up a job as a professor at the Art Students League of New York (Meisler). In New York Chase was able to build his reputation as a rising artist and art collector. Upon solidifying his financial standing, Chase was able to purchase a spacious two-story suite which he soon furnished with an eclectic flair (Meisler).

Chase had become fast friends with another rising artist, John Singer Sargent. Inspired by Chase’s studio and eager to put it to use, Sargent arranged for a private performance by Carmencita on April 1, 1890. Carmencita was a young Spanish dancer who, at the time, was well known throughout France and America (Fig. 1). Chase was inspired to paint a portrait of the guest of honor, Carmen Dauset, flamenco dancing for the audience. An 1894 recording below gives a sense of the performance.

Fig. 1 - Benjamin J. Falk (American, 1853-1925). Carmencita, ca. 1890. New York: Jerome Robbins Dance Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Source: National Endowment for the Humanities

1894 recording of Carmencita dancing. Source: Youtube

Chase painted the image in his signature impressionistic style. Brisk, rough brush strokes were used to illustrate Carmencita in her natural state of motion. Furthermore, a bouquet of flowers were laid at her feet and a slim golden bracelet was painted floating towards her, as if her audience were showering her with tokens of adoration.

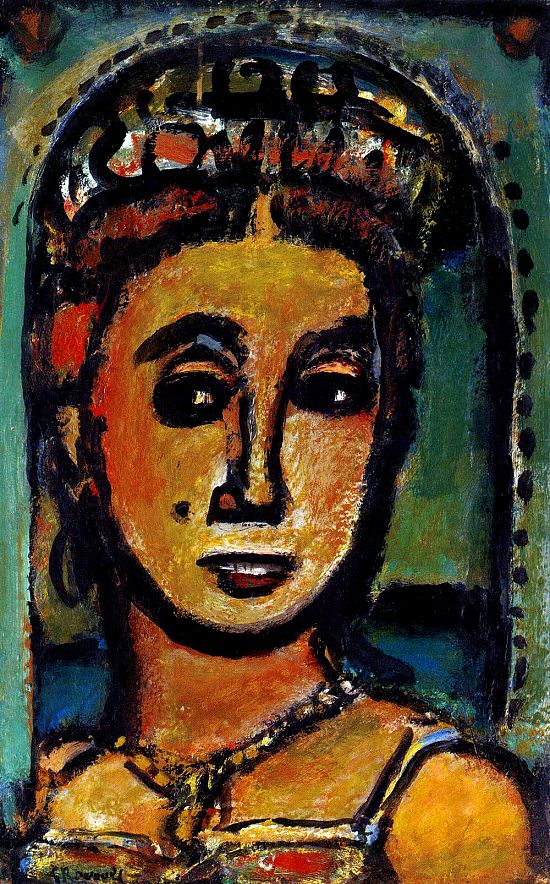

Carmencita was painted by numerous other artists as well—Sargent, James Carroll Beckwith, and Georges Rouault (Figs. 2-4).

Fig. 2 - John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). La Carmencita, ca. 1890. Oil on canvas; 232 × 142 cm (91 5/16 × 55 7/8 in). Paris: Musée d'Orsay. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 3 - James Carroll Beckwith (American, 1849-1916). Carmencita, 1907. Oil on canvas; 81.3 x 64.8 cm (32 x 25.5 in). Private Collection. Source: The Athenaeum

Fig. 4 - Georges Rouault (French, 1871–1958). Carmencita II, 1947. Oil on card laid down on panel; (19 1/8 x 12 1/8 in). Paris: Galerie Sophie Scheidecker. Source: Galerie Sophie Scheidecker

Her fame further escalated to the point were Carmencita soon became:

“The first dancer ever filmed…whose repertoire included flamenco styles like the peteneras, fandangos, and sevillanas. She was filmed in the studios of Thomas Edison, who had recently invented the motion picture camera. And this was no fluke—Carmencita was enormously famous in America, and her image lent prestige to the new medium of moving pictures.” (Zern, Brook Zern’s Flamenco Experience)

However, none were able to capture the combination of the dancer’s exuberant passion, personality, aura, movements, and audience quite as well as Chase had within his painting. Thus, it was received by his audience as a yet another mark of his talents, and it served to increase his readily growing reputation.

William Merritt Chase (American, 1849-1916). Carmencita, 1890. Oil on canvas; 177.5 x 103.8 cm (69 7/8 x 40 7/8 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 06.969. Gift of Sir William Van Horne, 1906. Source: The Met

About the Fashion

In this painting, Carmencita is dressed in a combination of traditional and contemporary styles. As a flamenco dancer, she wears a costume consisting of pieces designed to enhance her performance. Carmencita is depicted wearing an opulently embellished black dress, most likely designed in reference to her Hispanic heritage.

Taking inspiration from the late Renaissance, a gold and black color scheme was selected creating a warm, inviting mood. The exterior of the skirt is decorated with a fairly simple pattern, sewn using gold ribbons. It is presumed that the fabric of the dress is made of black silk taffeta due to the way the skirt catches the light in the painting. Taffeta is a fairly lightweight material, and would be appropriate for a dancer’s swift motions during performances. Furthermore, the short hemline was most likely tailored to accommodate the dancer’s constant movements without danger of obstruction or injury.

Overall, this almost crinoline-like silhouette is fairly outdated; although not visible in the painting, some type of crinoline is worn beneath Carmencita’s skirt to support its bell-shaped structure. During this time period tailor-made, more masculine styles were becoming increasingly popular. Women began wearing high collars with ties (depending on the occasion), loose blouses, less structured skirts, leg-of-mutton sleeves, and bolero jackets (1890-1899).

In comparison to the evening gowns of this period, Carmencita’s dress remains within the socially acceptable boundaries in terms of decolletage. During the late 1800s, women were still baring large portions of their skin from chest to arms, though the hemline was much shorter than would have been worn by women everyday.

Beneath the dress, Carmencita likely wore a pair of cotton drawers, suitable for proper ventilation during physical exertion and coverage beneath the dress. Then, in order to achieve the fashionable hourglass shape, Carmencita would have also worn a tightly-fitted corset. This style of corsetry was quite popular during the time period, as the cinched waist created extremely curvy silhouettes that balanced out the increasingly masculine style of women’s clothing.

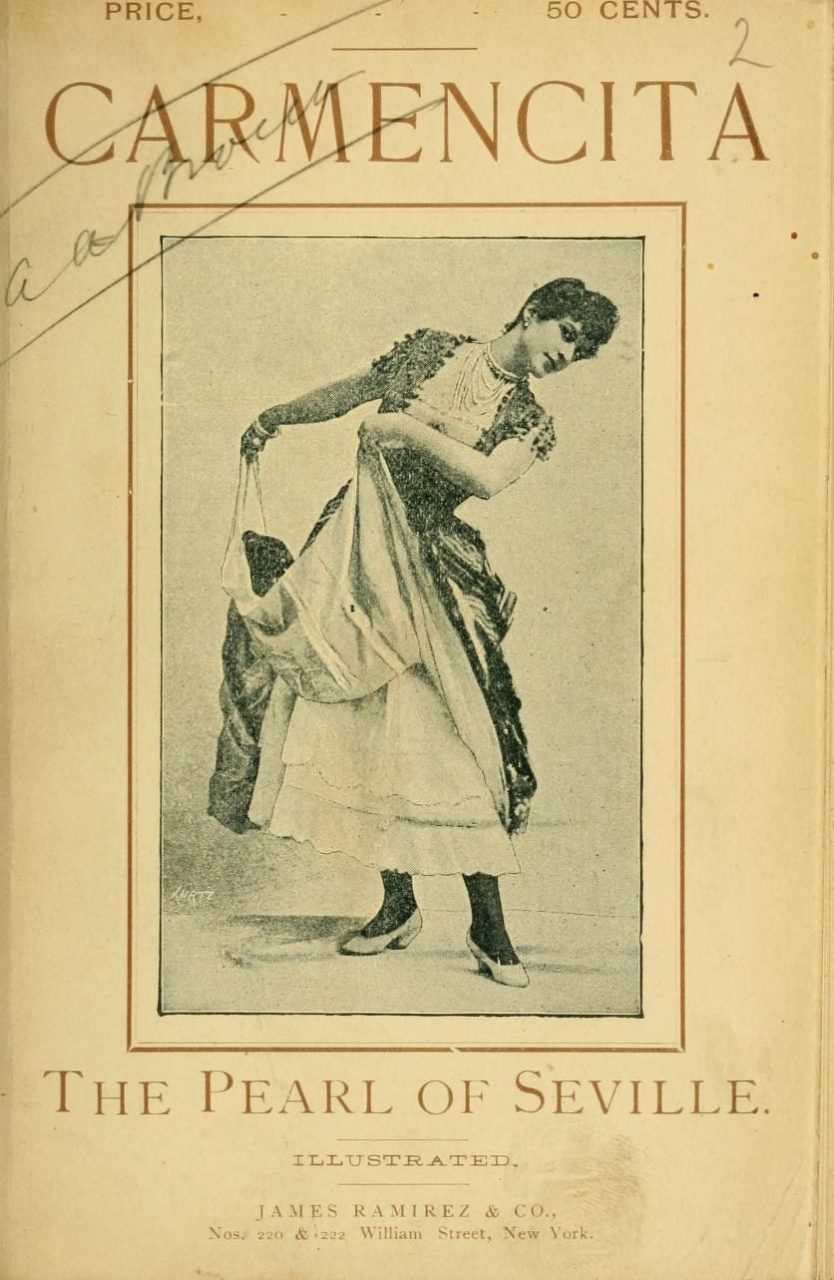

Her extravagant dress is accessorized with diamond earrings and gold accessories. These pieces are not only symbolic of her heritage, but also of the reputation and stature Carmencita had achieved as a famed performer, becoming known as the “Pearl of Seville” (Fig. 5) (Metropolitan Museum of Art).

On the other hand, not all features of Carmencita’s outfit in Chase’s painting were outdated. During this time period, natural beauty was heralded. Women were held to a standard of fresh, makeup-free faces—with the exception of powder—to create a glowing alabaster finish. Hair was also expected to reflect the ideal, and loose unrefined curls, twists, or plaits were common in hairstyling. It was because of these standards that Carmencita was forced to remove all traces of makeup from her face and restyle her hair into a high coiffure, as depicted in the painting (Meisler).

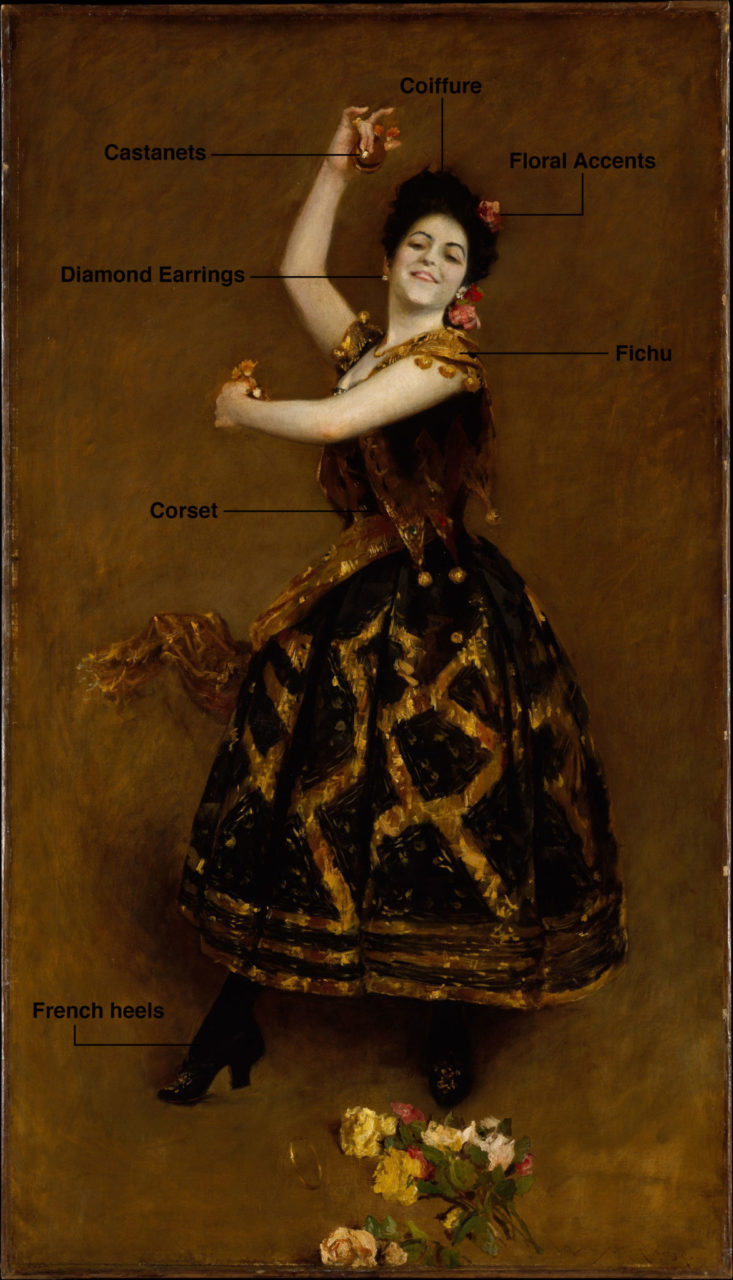

Carmencita wears fashionable black heeled shoes with gold patterns, stockings, festive floral hair accents, a delicate gold necklace, small pearl earrings, gold clams, and a jewel-encrusted shawl. The shawl, worn draped across her shoulders and tied around her waist, was lavishly decorated with jewels and gold medallions attached to the lining of the shawl. Furthermore, the shawl was embroidered with gold thread—increasing the air of opulence and beauty, and further emphasizing her status as a celebrity. As for the French heels, they were commonly worn as evening slippers (Vintage Victorian). However, upon looking closely, the leather shoes Carmencita wears are quite delicately decorated with gold patterns like those seen in figure 6.

In comparison to John Singer Sargent’s painting (Fig. 2), Carmencita is quite similarly dressed in an exuberant fashion. Both feature a similar bell shaped skirt with a short hemline, sashes, rich golden hues, floral accents, and highly embellished garments. In both paintings, her confidence exudes from her dynamic poses. However, what distinguishes Chase’s portrait from Sargent’s is the energy created by painting the subject in motion.

Decades later Mainbocher (Fig. 7) would create a dress with a similar silohuette and color scheme, affirming Carmencita’s fashion-forward stylishness.

Fig. 5 - James Ramirez & Co. (American). Cover of "The Pearl of Seville", 1890. Photomechanical print. Boston: Boston Public Library Rare Book Department. Source: Archive.org

Diagram of referenced dress features.

Source: Author

Fig. 6 - Maker unknown (American or European). Shoes, late 1880s–early 1890s. Leather, silk, glass. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1978.295.19a, b. Purchase, Marcia Sand Bequest, in memory of her daughter, Tiger (Joan) Morse, 1978. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 7 - Mainbocher (American, 1890–1976). Evening dress, ca. 1938. Silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.46.4.1. Gift of Mrs. Harrison Williams, Lady Mendl, and Mrs. Ector Munn, 1946. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

References:

- “Finishing Touches.” Vintage Victorian: 1890s Costume Accessories, 2011. Accessed November 30, 2015. http://www.vintagevictorian.com/costume_1890_acc.html

- Genocchio, Benjamin. “ART REVIEW; When Artists Collide.” New York Times, February 11, 2007. Accessed November 7, 2015. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9503E4DA113FF932A25751C0A9619C8B63

- Meisler, Stanley. “William Merritt Chase by Stanley Meisler.” Smithsonian Magazine,February 2001. Accessed November 16, 2015. http://www.stanleymeisler.com/smithsonian/smithsonian-2001-02-chase.html

- Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Carmencita.” Accessed November 6, 2015. http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/10465.

- Peltakian, Danielle. “WILLIAM MERRITT CHASE.” Sullivan Goss: An American Gallery. Accessed December 20, 2015. http://www.sullivangoss.com/william_merritt_chase/.

- Pisano, Ronald G. The Complete Catalogue of Known and Documented Work by William Merritt Chase (1849-1916). New Haven, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/316660264

- “Spanish Dresses – Traditional Spanish Clothing | Don Quijote.” Don Quijote. Accessed November 18, 2015. http://www.donquijote.org/culture/spain/society/customs/spanish-clothing

- Udall, Sharyn R. Dance and American Art: A Long Embrace. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2012. 117-119. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1059017486

- Weinberg, H. Barbara. “William Merritt Chase (1849–1916).” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Accessed December 19, 2015. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/chas/hd_chas.htm.

- Zern, Brook. “The Amazing American Odyssey of the Sensational Spanish Dancer Carmencita and the Legendary Flamenco Singer Rojo El Alpargatero.” Brook Zern’s Flamenco Experience. Accessed December 23, 2015. http://www.flamencoexperience.com/blog/?p=512.