The church of San Vitale in Ravenna is one of the most important Byzantine monuments in northeastern Italy. The basilica is fully decorated by mosaics, including two depicting Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora, which reveal the key features of sixth-century imperial style.

About the Mosaics

On both sides of the main apse of the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy, the Byzantine imperial court is represented in mosaic. Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora offer a paten and a chalice to the church (Andreescu 708). The mosaics glorify the imperial autocracy because, at this time, Justinian was expanding the Byzantine empire throughout the Mediterranean and had conquered the Ostrogothic capital Ravenna (Andreescu 708). Andreescu points out that in addition to the imperial glorification there is the attempt to show two local officials, Belisarius and Maximianus, in close connection to the emperor (they stand to his right), supporting their political power in Ravenna (Andreescu 721-722; Thomas 72-73).

Thus, these two are important scenes to understand the political situation and to give an idea of Byzantine imperial clothing during the sixth century CE.

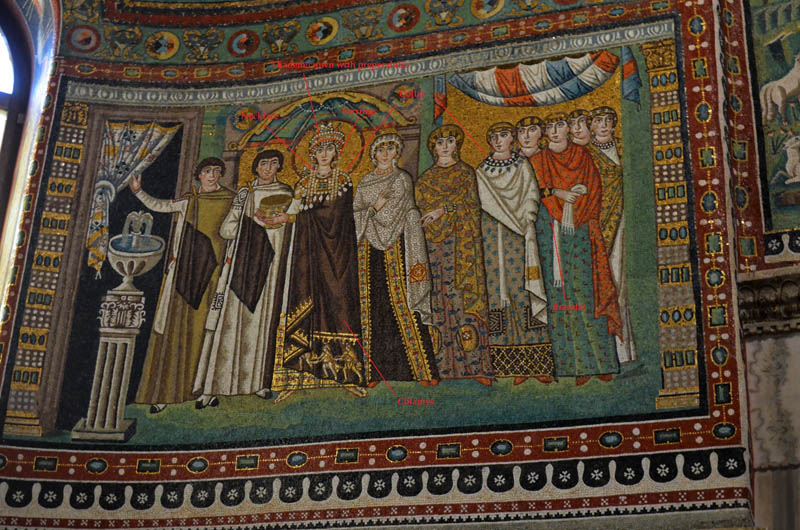

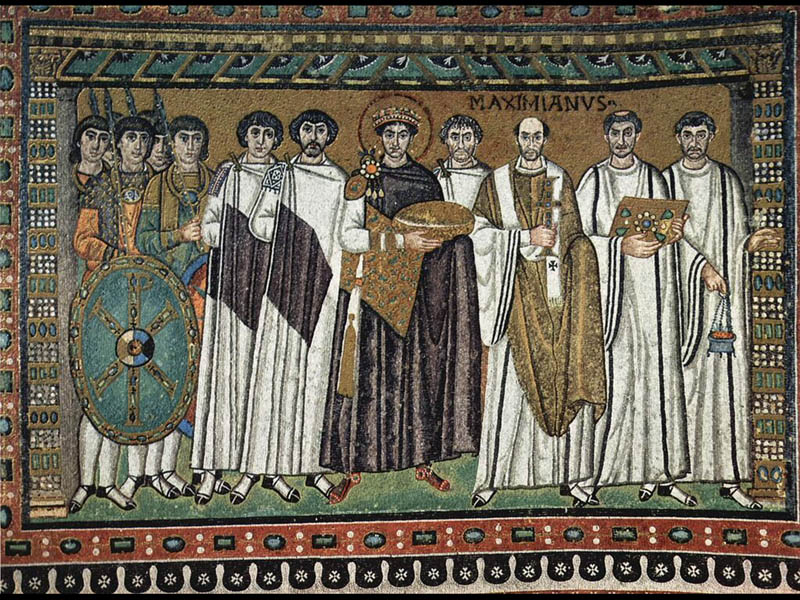

Artists unknown (Byzantine). Court of Emperor Justinian with (right) archbishop Maximian and (left) court officials and Praetorian Guards; in Ravenna, Italy, c. 547 AD. Ravenna: Basilica of San Vitale. Source: The Met

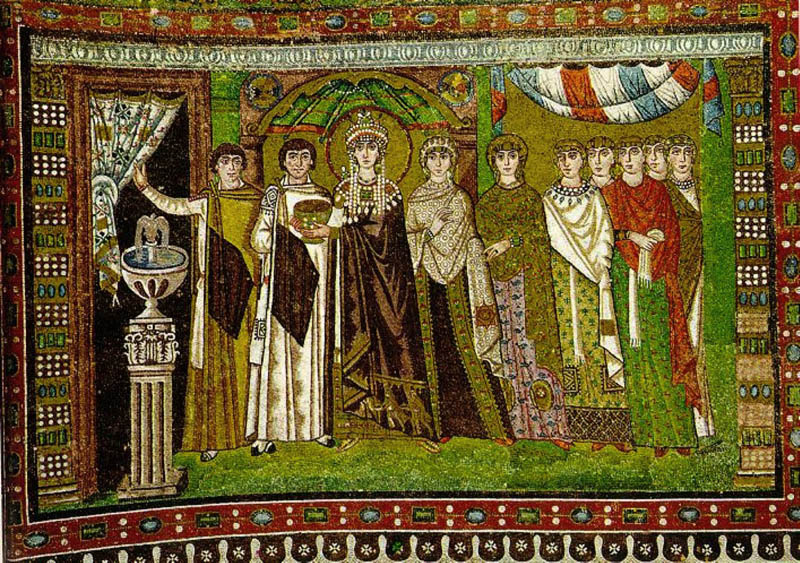

Artists unknown (Byzantine). Empress Theodora and Her Court; Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy, c. 547 AD. Ravenna: Basilica of San Vitale. Source: The Met

Justinian Mosaic

The emperor during late antiquity didn’t wear Roman magistrate dress anymore, but new imperial clothing that derived from the military one. In this mosaic Justinian wears a white knee-length tunic (divitision), decorated with golden bands (clavi) and a pair of purple leggings (tibialia). On his feet he wears a pair of purple sandals ornamented with precious stones, called campagi. Over the tunic, he wore a purple cloak (chlamys), which is pinned on by a brooch with pendants and is decorated on the right side with the tablion, an embroidered square of fabric (Ravegnani 136-138; D’Amato 12). In this case, the tablion is decorated with birds encircled by a golden background; roundels filled with figures and animals were very common in Byzantine textile designs (Figs. 1,2/ Muthesius 1997). The chlamys was a trapezoidal piece of fabric, which should be distinguished from the square or rectangular pallium, which became smaller in the ecclesiastical clothing (Martorelli). At last, Justinian wore a crown (stemma) fully decorated with precious stones and four pendilia (Ravegnani 138-139).

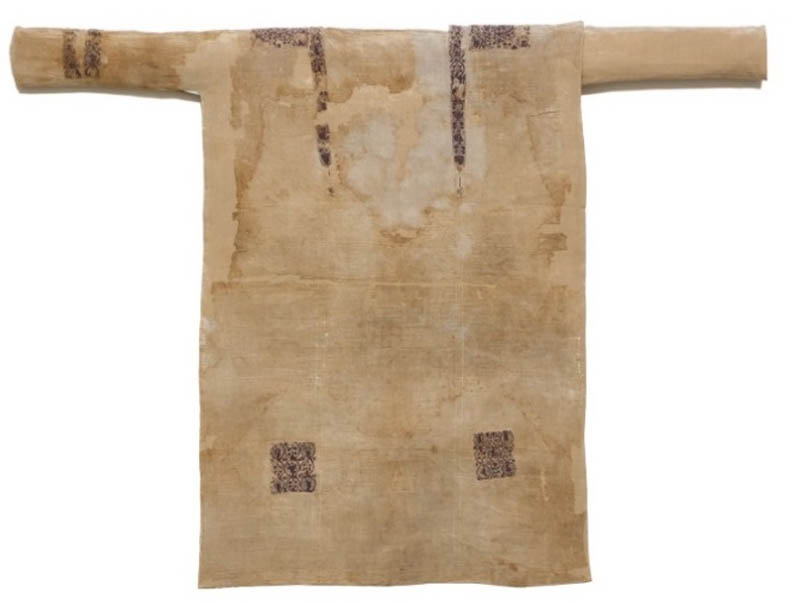

The tunic worn by Justinian was a simple T-shaped garment that reached to the knees, with sleeves and was tightened by the cingulum militiae. Tunics were usually made of wool, linen, silk, or occasionally cotton, and were woven in on piece, folded in half, and then sewn on the sides. Tunics often featured embroidered decorative appliqués around the neck opening, on the wrists, hems, cuffs, or on the lower part of the tunic (Fig. 3). As shown in the Justinian panel, pure white tunics were reserved for the emperor and were finished with gold embroidered decorations (D’Amato 8-16).

The belt was a military symbol and it was used to identify soldiers from civilians. At the turn of the 4th and 5th centuries, the leather belt was characterised by bronze and iron plates, which were ornamented or chiselled. During the 6th century these also featured pendants. In this case, Justinian wore a simple, ungilded belt, unlike the one described by the sources on imperial clothing (Ravegnani 137-138; D’Amato 17).

Eastern-derived leggings (tibialia) were used from the 5th century onwards and, like the belt, became a distinctive sign of military status. These leggings then became a basic piece of military uniform, in association with the tunic (D’Amato 18). Tibialia were usually worn with campagi, a kind of shoes made of wool or felt, which covered only the toes and heel and were fastened with laces or a buckle (D’Amato 20-22).

Fig. 1 - Creator unknown (Egyptian). Round insert of a tunic, 5th-7th century AD. Linen and wool; 5.5 cm diameter. Berlin: Berlin State Museum, 4600. Source: SMB Digital

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown. St. Servatius (Maastricht) fabric with Dioscurides, 8th-9th century AD. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 3 - Creator unknown (Egyptian). Tunic, 3rd-6th century AD. Linen, wool. Berlin: Berlin State Museum, 9918. Source: SMB Digital

The guardsmen wear a richly decorated, colorful tunic called a paragauda due to the embroidered ornaments, with white tibialia and black campagi. They also wear a rigid circular necklace called a torque (D’Amato 45).

The two officials to the right of Justinian, identified as Anastasius and Belisarius, wear a tunic with a symbol on the right shoulder, which could be a sign of their rank (D’Amato 37; Ravegnani 140). They also wore a white chlamys pinned by a crossbow brooch and decorated with a purple tablion. At last, leggings and black campagi complete the look (D’Amato 37).

Justinian gave Maximian, the bald man who stands to his left, the title of archbishop and this elevation might be confirmed by his garment and the pallium, a strip of cloth ornamented by crosses draped around his head (Heyward 302). The pallium must also be link with the ambitions of the bishops of Ravenna against Rome (Delyannis 210-211; Hayward 302; Serfass). Under his pallium Maximian wears a tunic and a golden paenula, which probably derives from chlamys because it seems open on the right (Hayward 303).

The deacons wear a tunic like Maximian’s with wide sleeves and decorated with black clavi (stripes). This type of tunic could be the tunica alba, which was the garment intended for deacons between the 5th and the 9th centuries (Hayward 302; Encyclopaedia Britannica).

Theodora Mosaic

Fig. 4 - Creator unknown (Byzantine). Gold Necklace with Pearls and Stones of Emerald Plasma, 6th-7th century AD. Gold, pearls, emerald plasma. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 17.190.153. Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917. Source: The Met

The empress wears a white tunic decorated on the edge by gold embroidery and a purple chlamys decorated on the hem with images of the three Magi offering gifts to Christ. Theodora wears elaborate jewelry: a necklace, a collar, a pair of earrings, and on her head a diadem with precious stones and prependulia (Deliyannis 240; Ravegnani 138).

An interesting aspect of Theodora’s clothing is that she wore a chlamys, a cloak that was used by soldiers and by emperors. In a broader sense, the purple chlamys symbolized the military and imperial power and therefore this explains why this garment wasn’t typically used by women, but in this case the purpose is to make the empress recognisable among other figures and to create a connection between Justinian and Theodora as an imperial couple (Barber 36).

The two attendants on her right wear the same clothing as the men in Justinian’s panel and the women like Theodora wear more ornate and colourful tunics and stoles and their heads are covered by something like a cap.

Fig. 5 - Creator unknown (Roman). Earrings and necklace, 4th century AD. Gold, pearl, emerald, sapphire. London: British Museum, AF.324.325. Bequeathed by Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks. Source: British Museum

Fig. 6 - Creator unknown. Collar, 6th century. Gold, pearls, aquamarine; 23 x 58 cm. Berlin: Staatlichen Museen, 30219, 505. Found in Egypt. Source: Staatlichen Museen

Fig. 7 - Creator unknown (Byzantine). Jeweled Bracelet, 6th-8th century AD. Gold, silver, pearl, amethyst, sapphie, opal, glass, quartz, emerald plasma. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 17.190.1670. Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917. Source: The Met

The jewellery in Theodora’s panel can be compared with some archaeological finds. The necklace worn by Theodora is similar to one in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which is made of gold, emerald and pearls (Fig. 4/ Brown 58-59). The earrings worn by Theodora and two ladies are of the same type: a ring with a suspended square emerald, a pearl and a sapphire; you can see similar earrings from the Carthage Treasure dated around 400 (Fig. 5/ Brown 61). This comparison suggests the continuity of the same style in the imperial workshops of the 6th and 7th centuries (Brown 61). Regarding Theodora’s collar and crown, no material comparison can be made, but a similar example of the collar worn by one of the ladies can be seen in the Antikenmuseum in Berlin (Fig. 6/ Brown 57). The collar is made of openwork gold plaques on which precious stones are set and all the plaques have a pendant. In the Metropolitan Museum, there is a bracelet made with the same technique and completely covered with pearls and precious stones, like the one worn by the fourth lady on Theodora’s left (Fig. 7/ Brown 59-60).

Diagram of referenced dress features.

Source: Author, based on thebyzantinelegacy image

Diagram of referenced dress features.

Source: Author, based on thebyzantinelegacy image

References:

- “Alb” in Encyclopaedia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/topic/alb

- Andreescu-Treadgold, Irina, Treadgold, Warren. “Procopius and the Imperial Panels of S. Vitale.” In The Art Bulletin, v. 79 (1997): 708-723. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/887266064

- Barber, Charles. “The imperial panels at San Vitale: a reconsideration.” Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, v. 14 (1990): 19-43. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/8272290165

- Brown, R. Katharine. “The Mosaics of San Vitale: Evidence for the Attribution of Some Early Byzantine Jewelry to Court Workshops.” In Gesta, v. 18, no. 1 (1979): 57-62. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/888607450

- D’Amato, Raffaele and Graham Sumne. Roman Military Clothing, AD 400-640. Oxford: Osprey, 2005. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/773797167

- Hayward, Jane. “Sacred Vestments as they developed in the Middle Ages in Ecclesiastical Vestments of the Middle Ages. An Exhibition.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, v. 29 (1971). http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/83159878

- Martorelli, Rossana. “Influenze religiose sulla scelta dell’abito nei primi secoli cristiani in Tissus et vetements.” In l’Antiquité Tardive, actes du colloque de l’Association pour l’Antiquité Tardive, 231-252. Lyon: Musée Historique des Tissus, Turnhout, 2005.

- Mauskopf Deliyannis, Deborah. Ravenna in Late Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1083205730

- Muthesius, Anna. “‘Being’ in Constantinople (4th-15th centuries) witnessed through the testimony of precious textiles.” In Deltion tes Christinikes Archaiologikes Hetaireias, v. 38 (2017): 333-354. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1078670920

- Ravegnani, Giorgio. L’età di Giustiniano. Rome: Carocci editore, 2019. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1223518160

- Serfass, Adam. “Unraveling the Pallium Dispute between Gregory the Great and John of Ravenna.” In Dressing Judeans and Christians in Antiquity, eds Kristi Upson-Saia, Carly Daniel-Hughes, Alicia J. Batten. New York: Routledge, 2014. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1155169181

- Thomas, Brittany. “A Case for Space. Rereading the Imperial Panels of San Vitale.” In Debating Religious Space and Place in the Early Medieval World, eds. Chantal Bielmann, Brittany Thomas. Leiden: Sidestone Press, 2018. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1052877878