The boubou is an African robe made of one large rectangle of fabric with an opening in the center for the neck. When worn it drapes down over the shoulders and billows at the sleeves.

The Details

In the Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion (2005), Leslie W. Rabine describes the boubou as:

“the classic Senegalese robe, worn by both men and women all over West Africa and in West African diasporic communities of Europe and the United States. Sewn from a single piece of fabric, the boubou is usually 59 inches (150 cm) wide and of varying lengths. The most elegant style, the grand boubou, usually employs a piece of fabric 117 inches (300 cm) long and reaches to the ankles. Traditionally, custom-made in workshops by tailors, the boubou is made by folding the fabric in half, fashioning a neck opening, and sewing the sides halfway up to make flowing sleeves. For women the neck is large and rounded; for men it forms a long V-shape, usually with a large five-sided pocket cutting off the tip of the ‘V.’

When stiffly starched and draped over the body, the boubou creates for its wearer the appearance of a stately, elegant carriage with majestic height and presence. Men wear the classic boubou with a matching shirt and trousers underneath. Women wear it with a matching wrapper or pagne and head-tie.”

This traditional blue indigo-dyed boubou (Fig. 1) is decorated with geometric and figural embroidery which shows the prestige and importance of the wearer. These Islamic motifs were for protection and this boubou was only worn for special occasions.

In the Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: Africa (2010), Babatunde Lawal explains a possible origin for the boubou:

“It has been suggested that the Berbers/Tuaregs from North Africa might have introduced some of these robes and trousers to western and central Africa in the course of the trans-Saharan trade that started before the Christian era and lasted until the late nineteenth century. Some of the earliest evidence of the flowing robe in sub-Saharan Africa comes from a ninth-century c.e. burial site excavated at Igbo-Ukwu in eastern Nigeria.”

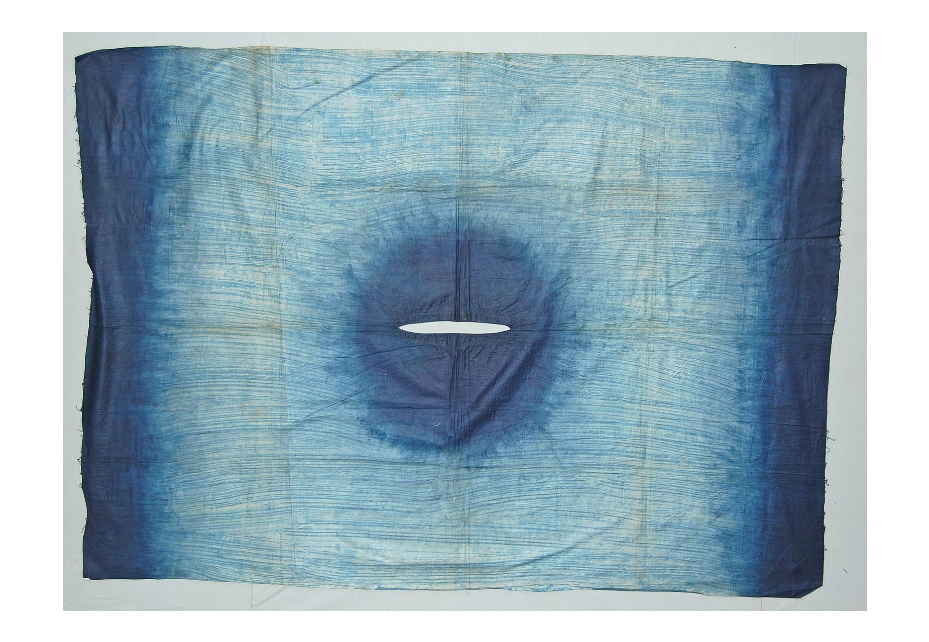

This indigo-dyed cotton robe (Fig. 2) is a single piece of fabric which creates the flowing drapery on the body. There is a slit in the center where the wearers head goes through then the rest of the fabric drapes down.

Fig. 1 - Maker unknown (African). Man's robe, 1920s-1930s. Cotton and wool; 91.4 x 167.6 x 0.6 cm (36 x 66 x 1/4 in). Boston: Museum Of Fine Arts, 2017.4649. Year-end gift of Margarete Wells to the MFA. Source: MFA

Fig. 2 - Maker unknown (African). Robe (boubou), 1934. Cotton; 126 x 172 cm. London: The British Museum, Af1934,0307.251. Donated by Charles A Beving. Source: British Museum

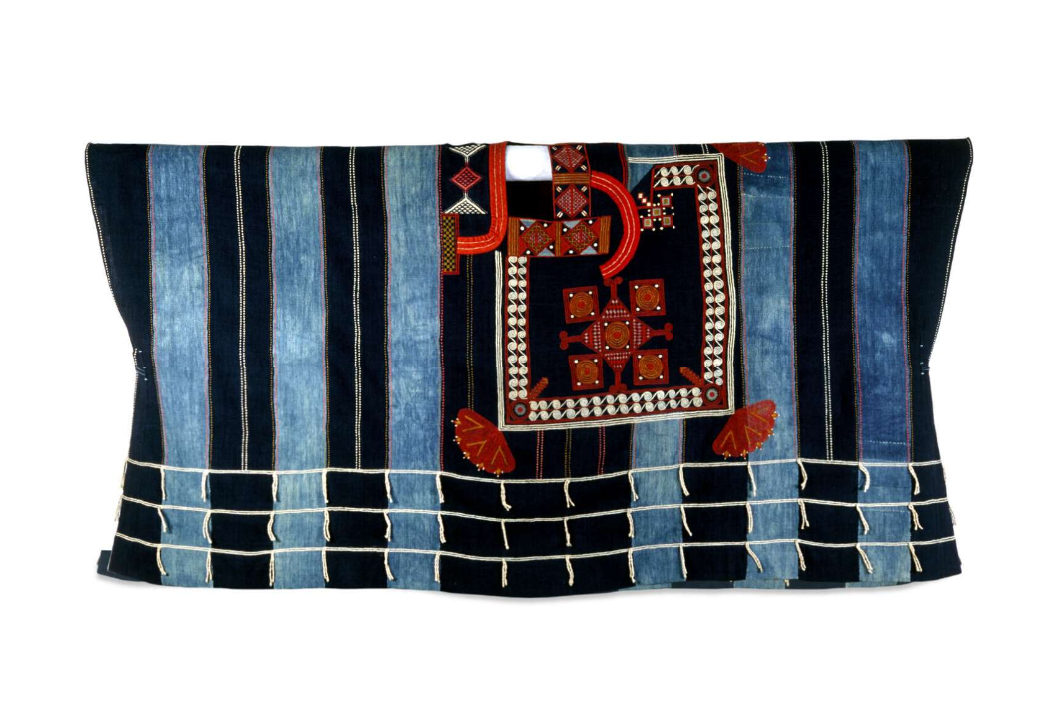

Fig. 3 - Maker unknown (African). Gown, 19th century (early). Cotton; 180 x 92 cm. London: The British Museum, Af.2798. Donated by Henry Christy. Source: British Museum

Fig. 4 - Maker unknown (African). Chief's shirt (boubou), second half 19th century. Cotton plain weave (strip woven), embroidered with wool; 94 x 152.4 cm (37 x 60 in). Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2004.551. Museum purchase with funds donated by Jeremy and Hanne Grantham. Source: MFA

The boubou can also be designed with patterns and imagery. This boubou (Fig. 3) includes alternating strips of fabric sewn together. Both fabric sections are indigo dyed, one being light blue and the other being dark to create a contrasting striped pattern. Around the squared neck hole is geometric hand-sewn embroidery in red, white, brown, and black.

While traditionally a robe for men, in the twentieth century women also began to wear a version of the boubou, as Lawal notes:

“Women sometimes wear a loose blouse or robe (called boubou in Senegambia and Mali) on top of their wrappers.”

In the Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: Africa (2010), Hudita Nura Mustafa explains the complexity of the boubou:

“While building upon enduring forms and values, dress also possesses a fertile capacity to evolve. For example, billowing boubous, robes of six meters (twenty feet), simply cut and often richly embroidered around the neck, are recognized the world over as traditionally West African. Yet the boubou is not a static symbol of origin but an object of dynamic dialogue between tradition and modernity, hybridity and authenticity. It was further spread by Islamization in the nineteenth century and, while the basic form stays constant, it has its own fashions.”

Mustafa further elaborates:

“Although the basic categories of dress are traditional/African and modern/European, the diversity of styles transcends this opposition. These categories are symbolized in the French suit, the attire of the civilized black Frenchman, and the embroidered boubou, the attire of the traditional Muslim man. The embroidered boubou is, and has always been, the pinnacle of prestige. African dress is associated with religious and traditional ceremonial events, domestic space, and modesty.”

This cotton boubou (Fig. 4) made for a man is embroidered with red, white and blue wool has a squared neck opening for a more masculine effect. The length of this boubou is more conservative and not particularly long and the geometric designs depicted across the front and back show how customizable this garment is.

References:

- Lawal, Babatunde. “Body and Beauty.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: Africa, edited by Joanne B. Eicher and Doran H. Ross, 77–83. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2010. Accessed March 03, 2021. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/BEWDF/EDch1012a

- Mustafa, Hudita Nura. “Senegal and Gambia.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: Africa, edited by Joanne B. Eicher and Doran H. Ross, 228–236. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2010. Accessed March 03, 2021. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/BEWDF/EDch1034

- Rabine, Leslie W. “Boubou.” In Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele, 175-177. Vol. 1. Detroit, MI: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2005. Gale eBooks (accessed March 3, 2021). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX3427500085/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=843ea4b0 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1028427618.