The fibula, which was popular in Greek culture, served as a pin to both hold garments together and to show status of those with prestige or power within society.

The Details

B

igelow in Fashion in History: Western Dress, Prehistoric to Present (1979) describes the fibula’s function and evolution:

“The fibula was a functional and a decorative accessory used by men and women. The early form was simply a bent wire with a sharp point on one end and a hook latch on the other. As Greek culture became more sophisticated, fibulae developed into elaborately decorated, large pins fashioned in many diverse shapes. They were made of precious metals with intricate, chased designs and became important costume accessories.” (63)

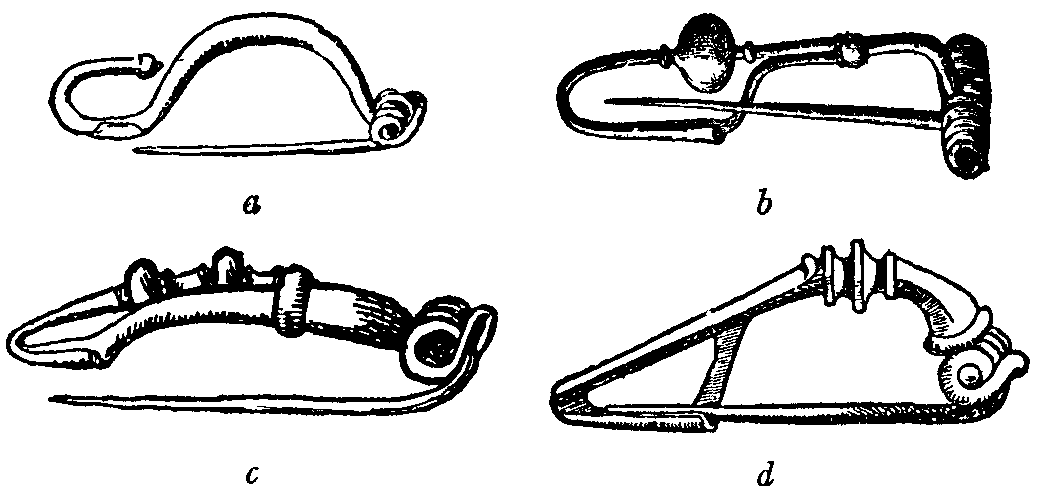

A fibula’s main use was acting as a safety pin to hold up a draping garment and act as an accessory that showed status or power. Although some of the fibula had their own unique shape, Figures 1, 3, and 4 feature the now classic safety pin silhouette, as Yarwood in the Encyclopedia of World Costume (1978) notes: “the designs resembled the modern safety pin in structure and appearance” (180).

According to Blanche Payne, author of History of Costume: From the Ancient Egyptians to the Twentieth Century, the fibula was an “ornamental clasp” used to fasten garments, typically at the right shoulder (27).

Arnold describes the fibula’s decoration in the Berg Fashion Library writing:

“The metal components of the fibula could be decorated or augmented with other material, either in the form of beads made of amber or glass threaded on the wire elements, or as inlays in the cast components of the fibula, often in the form of coral buttons or rods. Various bronze objects could also be threaded on the pin or suspended from fine chains with sheet bronze “noise makers” on the ends.”

Figure 4 features just such a decorative amber bead and Figure 5 includes small bells attached to fine chains.

In addition to being a fashion accessory, the fibula found its significance as a votive gifts for gods and goddesses, of which the Penn Museum (1964) writes:

“For example, at a sanctuary on the island of Rhodes about sixteen hundred fibulae were found in votive deposits, and at least one sanctuary deposit, that at Ephesus, contained pieces of thin gold and silver foil cut into the form of fibulae. These simulacra could not possibly have been worn and were made only for the purpose of dedication. Furthermore, at Nimrud in Assyria, a limestone plaque was found on which was depicted a female demon or deity surrounded by objects, one of which appears to be a fibula. If these objects were votive gifts to the deity, as some scholars suggest, then we can assume that Assyrians as well as Greeks recognized fibulae as having some votive value. …if fibulae had some special value in sanctuaries, they may also have had some special value in a tomb where the dead person would soon come into contact with his gods. We know that the dead as well as the living wore fibulae. In fact, there is evidence that some dead persons wore a greater quantity of fibulae than was normal in daily dress. This difference becomes obvious when one examines the number of fibulae worn by people represented on sculpture, reliefs, or painted vases, and compares them to the number of fibulae often found associated with burials. In the former circumstances only a few fibulae, sometimes only one, are evident, whereas in the burials many more are often found. Thus the man buried under the big tumulus at Gordion was laid to rest with thirty-seven fibulae about his body and a bad containing 145 fibulae was placed near his bier. A child of three or four years found in an early Roman cemetery had nine fibulae placed on her body.”

Fig. 1 - Unknown. Fig. 9, a-d.—Fibula of the La Tène period, showing the development of the reflexed terminal, and the bilateral spring., 5th to 8th Century. Source: Encyclopedia Britannica

Fig. 2 - Unknown. Hellenistic Greek Braganza Brooch, 250-200 BC, British Museum, London, 250-200 BC. Gold; 14 cm long (5.51181 in long). London: British Museum. Source: Wikiwand

Fig. 3 - Unknown. Gold sanguisuga-type fibula (safety pin) with patterns in granulation, 7th century B.C.. Gold; 5.7 cm (2 1/4 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 31.11.1. Fletcher Fund, 1931. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 4 - Unknown. Bronze fibula (safety pin) with amber segment, 7th century B.C.. Bronze; 7 cm (2 3/4 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 96.9.317. Purchase, 1896. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 5 - Unknown. The unique inverted bow-shaped gold fibula of Kition, reference MLA 1742/20, 1450 BC. Gold. Source: Archeo Sciences

Its Afterlife

Alberta Ferretti’s Spring 2008 ready-to-wear collection provides a modern take on the Greek dress with fibula (Fig. 6). In Ossie Clark’s Spring 2009 collection, the fibula is used to pin a modern Doric chiton onto the left shoulder (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6 - Alberta Ferretti (Italian, 1950-). Chiton with fibula, Spring 2008. Source: Vogue

Fig. 7 - Ossie Clark (English, 1942-1996). Doric chiton with fibula over left shoulder, Spring 2009. Source: Vogue

References:

- Arnold, Bettina, and Sabine Hopert Hagmann. “Fibulae and Dress in Iron Age Europe.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: West Europe, edited by Lise Skov. Oxford: Berg, 2010. Accessed December 14, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/BEWDF/EDch81013.

- Bigelow, Marybelle S., and Kay Kushino. Fashion in History: Western Dress, Prehistoric to Present. 2d ed. Minneapolis, Minn: Burgess Pub. Co, 1979. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/861475003.

- Evans, Mary. Costume Throughout the Ages. Rev. ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1950. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/317083519.

- Muscarella, Oscar W. “Expedition Magazine | Ancient Safety Pins.” Penn Museum – University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaelogy and Anthropology. Accessed September 27, 2017. https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/ancient-safety-pins/.

- Payne, Blanche. History of Costume: From the Ancient Egyptians to the Twentieth Century. New York: Harper & Row, 1965. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/777277049.

- Yarwood, Doreen. The Encyclopaedia of World Costume. London: B. T. Batsford, 1978. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/638640462.