A flat length stay piece that was inserted into the front of a corset to keep it stiff from the 16th century to the early 20th century.

The Details

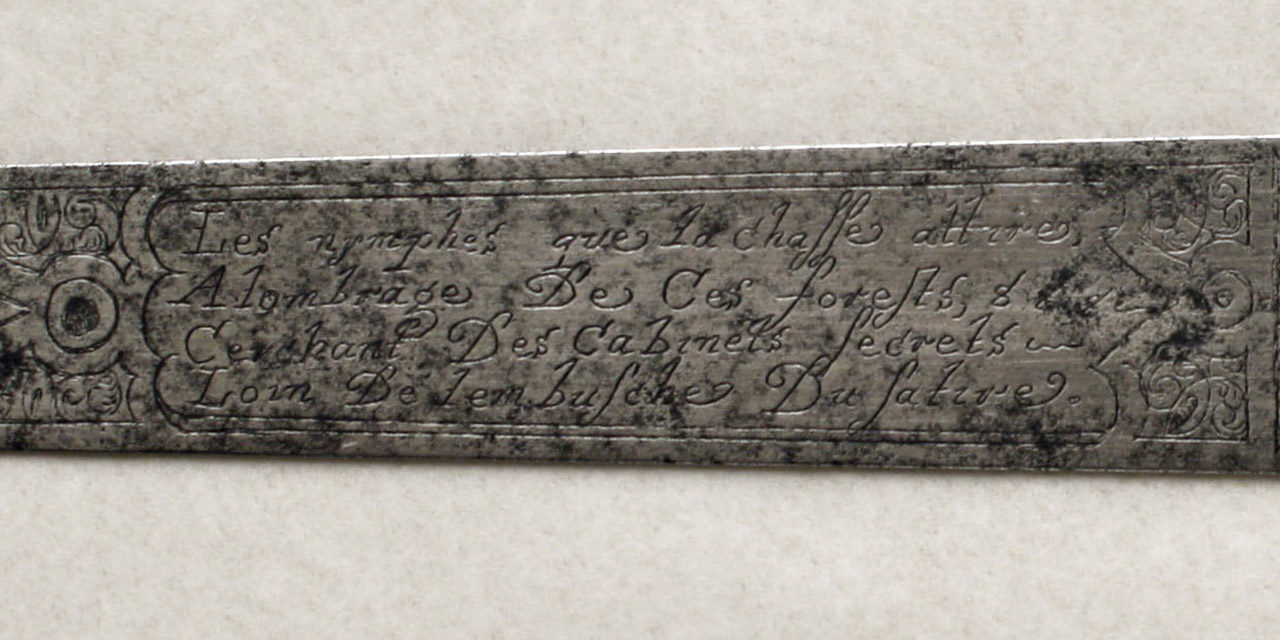

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown (French). Metal busk, 17th century. Metal. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 30.135.30. Gift of Mrs. Edward S. Harkness, 1930. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

T

he 17th-century French metal busk above, in the Met’s collection, is engraved with flowers and trophies of love and lines of a poem: “Nymphs, drawn to the chase and to the shadows of these forests searching some secret places far from the ambush of the satyr.” The busk was not just a narrow medium for poetry, however. As Alex Newman and Zakee Shariff in Fashion A to Z: An Illustrated Dictionary (2009) explain, the busk was:

“a strip of rigid material such as whalebone, wood, ivory, shell, or, more recently, steel, set into the center front of a woman’s corset to make it flat and straight. First used in the 16th c. Also spelled ‘busque'” (36).

Figure 2 is another 17th-century French example also with fine carving, but now made of ivory; the Met describes its decorations as depicting “women playing musical instruments, a bird lighting on a branch, and foliate scrolls on the front. On the back, clasped hands, flames, and a heart pierced by an arrow are represented.” Figure 3 demonstrates the international adoption of this dress item as it is an Italian busk carved out of wood.

Karen Baclawski in The Guide to Historic Costume (1995) explains further:

“A length of wood, whalebone, steel or similar material inserted in the front of stays from the sixteenth century until the beginning of the nineteenth century. The shape and length of busks varied with the fashion in stays; however, they were commonly twenty-five to thirty-eight centimetres long (ten to fifteen inches), thicker at breast level and slimmer at waist level, sometimes decorated and easily removable. Their role in lending greater rigidity to the stay and maintaining erect carriage of the torso remained constant.” (52)

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown (French). Busk, 17th century. Ivory. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 30.135.19. Gift of Mrs. Edward S. Harkness, 1930. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown (Italian). Thin wood busk, 1600–1825. Wood. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 30.135.24. Gift of Mrs. Edward S. Harkness, 1930. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The National Museum of American History explains why so many busks were carved:

“Many corsets were handmade to fit an individual, although they were also available in shops. One of the most intimate pieces of scrimshaw a whaleman could produce was a bone or baleen busk, or corset stiffener. These were carved and given to a crewman’s loved one, who then inserted it into a matching sleeve on her corset as a unique memento of her beloved’s feelings.”

See a 19th-century carved wooden busk in figure 4, likely produced by just such a love-struck suitor. All this whimsy faded from view, however, with the arrival of steel (Figs. 5-7).

Valerie Steele in the Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion (2004) explains:

“Traditionally, down the center front of the corset was inserted a busk, which, in shape and size, was not unlike a ruler. Busks were variously made of wood, horn, and whalebone; they were often elaborately carved ad given as lover’s gifts. By 1850 the traditional, inflexible one-piece busk had been replaced by steel, front-opening style, which made in much easier for women to put on and take off their corsets. Prior to this, women usually relied on assistance to lace and unlace their corset.” (290)

These front-opening corsets did still sometimes have messages on their busks, but of a more commercial sort. As the Met notes of their 1866-67 corset (Fig. 5): “Written in pencil on the busk is the date it was produced as well as the retailer it was produced for. The piece is a testament to the fact that manufacturers took specific orders from retailers, producing quality goods exclusively for them.” But rather than carved, the information was handwritten in pencil on busk casing: “Alamode/Made for Day * Horton/N.Y./1866 or 1867”

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown (Probably American). Wooden busk with design, 1825-50. Wood. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.38.68. Gift of Mrs. Aline Bernstein, 1938. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 5 - 1861–1872) Worcester Skirt Company (American. Corset, 1866–67. Cotton, metal, bone. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.3102a–c. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of E. A. Meister, 1950. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 6 - Crotty & Richards (American). Corset, ca. 1872. Cotton, metal, bone. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.3103a–c. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of E. A. Meister, 1950. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 7 - Maison Léoty (French). Corset, 1891. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.45.27a, b. Gift of Miss Marion Hague, 1945. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The shape of the busk also changed, as the Met explains when discussing their 1891 Maison Léoty corset (Fig. 7):

“In the eighteenth century, the corset imposed a more-or-less conical configuration to the upper torso. By the late nineteenth century, a more softly rounded female form was preferred. This extended even to the body in profile. The straight and rigid busks of the eighteenth century gave way to busks that not only curved into the waist but also rounded out over the belly.”

References:

- Baclawski, Karen. The Guide to Historic Costume. New York: Drama Book Publishers, 1995. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/60155138.

- “Busk | French | The Met.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed August 14, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/84190

- “Busk | French | The Met.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed August 14, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/85399.

- “Corset and Whalebone Scrimshaw Busk.” National Museum of American History. Accessed August 14, 2018. http://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1341776.

- Cumming, Valerie, C. W. Cunnington, and P. E. Cunnington. “Busk.” The Dictionary of Fashion History. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2010. 34. Bloomsbury Fashion Central. Web. 29 Sep. 2017. https://www.bloomsburyfashioncentral.com/products/berg-fashion-library/dictionary/the-dictionary-of-fashion-history/busk.

- “Maison Léoty | Corset | French | The Met.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed August 14, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/82433.

- Newman, Alex, and Zakee Shariff. Fashion A to Z: An Illustrated Dictionary. London: Laurence King Publishing, 2009. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/857551868.

- Steele, Valerie, ed. “Corset.” In Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion, 290. Scribner Library of Daily Life. Detroit: Thomson/Gale, 2005. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/441915435.

- “Worcester Skirt Company | Corset | American | The Met.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed August 14, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/158003.