A close-fitting men’s jacket, often worn for warmth, sometimes without sleeves. It was worn over a doublet in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The Details

P

hyllis Tortora and Sandra Keiser in The Fairchild Books Dictionary of Fashion (2013) define the jerkin as a “contemporary synonym for vest, waistcoat, and weskit,” explaining further that it was a:

“Man’s sleeved jacket worn over doublet, sometimes laced or buttoned up front, sometimes sleeveless with shoulder wings; worn from late 15th through 16th c.” (425)

The definition describes the new technologies for clothing in the 15th and 16th centuries such as closures and decorative sleeves as they were applied to the jerkin.

The jerkin was popular and part of the general dress in the 16th century, Sir Martin Frobisher is depicted wearing one in figure 1 after his journey to Newfoundland. The favored garment was included in King Henry VIII’s court’s attire. Dress at the Court of King Henry VIII (2007) describes the jerkin as:

“A short upper garment usually worn over the doublet, often sleeveless but could have long sleeves, also known as a jacket.” (434)

The Met’s research suggests that jerkins could also be worn under armor, which they believe is true of the 17th-century jerkin in their collection, based on wear patterns (Fig. 2).

Stuart Peachey in his book, Jerkins, Jackets, and Mandillions (2013), elaborates more on what exactly a jerkin was defined as according to different times in history:

“Jerkins were described as upper garments in a statue of 1616. It appears to be almost exclusively a male garment worn on the upper body… probably front opening.” (3)

His research shows that jerkins with upper garments made from different types of materials and had openings in the front. He also uses historical evidence to refute the modern concept of what a jerkin is thought to be:

“The modern concept of a jerkin defined by being a sleeveless garment, as opposed to a coat as a sleeved garment, does not hold water as there are examples of implicit or explicit sleeveless coats and coats with detachable sleeves.” (3)

The Met has a sleeveless, early 17th-century jerkin made of red velvet in its collection that closed via many small buttons (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1 - Cornelius Ketel (Dutch, 1548-1616). Sir Martin Frobisher, 1577. Oil on canvas; 211 x 98 cm (83 x 38.5 in). Oxford: The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (European). Jerkin, early 17th century. Silk, jute. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 35.98.2. Rogers Fund, 1935. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (British). Jerkin, 1610-25. Silk, cotton, linen, metal. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018.113. Purchase, Isabel Shults Fund, 2018. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Its Afterlife

The jerkin fell out of fashion in the late 17th-century. However, during WWI, the jerkin as a military garment was resurrected by the British Army. The early 20th-century jerkins were simple makeshift garments made from animal skins (Fig. 4). Their purpose was to provide warmth for the British and Commonwealth troops that served in the frozen trenches of the Western Front (US Militaria Forum).

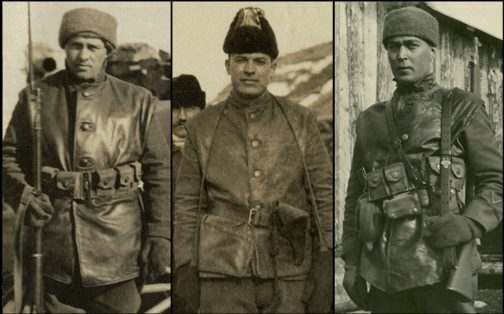

To build upon the regulation outer clothing of the British “Tommy,” during the first winter of World War I, improvised garments made from animal hides were issued on the Western Front for the Americans (“doughboys”). Sleeveless jerkins and jackets (with sleeves) were both issued and locally made from either sheepskin or goatskin. Some were manufactured with the fur or fleece to the outside, while others were made with the fur or fleece turned inside (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (American). Sheep and Goatskin Jerkins, 1910-19. Sheepskin, goatskin. Source: US Military AEF Forum

Fig. 5 - Designer unknown (American, British). Army Jerkins, 1910-19. Animal skins, leather. Source: US Military AEF Forum

References:

-

“A.E.F. Jerkins 1917 to 1919 – WWI US MILITARIA.” U.S. Militaria Forum. Accessed February 5, 2019. http://www.usmilitariaforum.com/forums/index.php?/topic/257929-aef-jerkins-1917-to-1919/.

- Ashelford, Jane, ed. A Visual History of Costume. London: Batsford, 1983. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/30651941.

- Hayward, Maria, ed. Dress at the Court of King Henry VIII. Leeds: Maney, 2007. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/997437672.

- Peachey, Stuart, ed. Jerkins, Jackets and Mandillions. Clothes of the Common People in Elizabethan and Early Stuart England, volume 12. Bristol: Stuart Press, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/881369731.

- Tortora, Phyllis G., Sandra J. Keiser, and Bina Abling. The Fairchild Books Dictionary of Fashion. 4th edition. New York: Fairchild Books, 2014. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/900349357.