The Norman Mosaics are a series of 12th-century artworks in churches across Sicily. The dress seen in these mosaics reflects Byzantine styles including the divetesion and loros. The mosaics have notably also served as inspiration for designers in the 21st century.

ABOUT THE MOSAICS

The Heuteville (Altavilla) family conquered Southern Italy and Sicily between the XI-XII centuries and commissioned the construction of important monuments. This article discusses two mosaic panels depicting Roger II (1130-1154) and William II (1166-1189). The first is located in the narthex of the Church of St Mary of the Admiral (La Martorana) in Palermo and the second near the presbytery of the Monreale Cathedral.

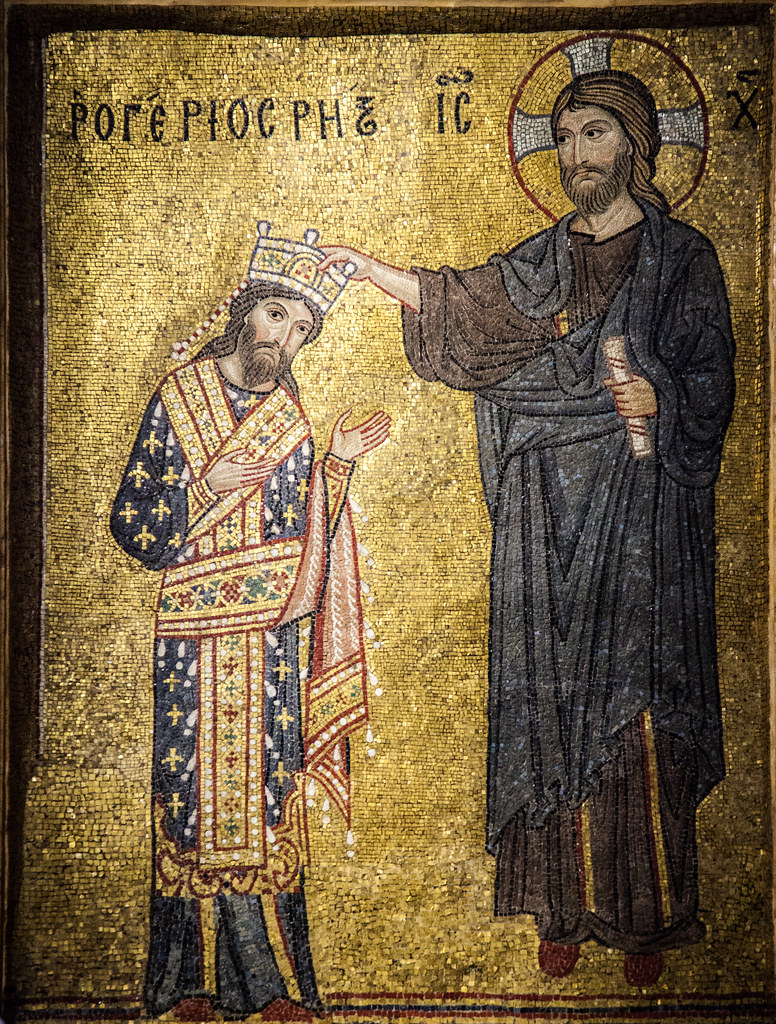

The Church of St Mary of the Admiral and its mosaics were commissioned by George of Antioch, a member of the court who wanted the portrait of the king to give prestige to the church and to indicate that his power was recognized by Roger II (Vagnoni 2017, 70). The portrait panel (Fig. 1) was probably made between 1143, the year the church was built, and 1151 (Vagnoni 2017, 49-55). Roger II is depicted next to a standing Christ, who holds a closed scroll in his left hand and crowns the king with his right. The latter holds his hands open and turned towards Christ, a gesture that signifies humility and adoration of the divine.

The Monreale complex was founded by William II and the first source that mentions the Cathedral dedicated to the Virgin dates to 1174. The architecture was probably constructed between 1172-1183 and the mosaics that completely decorate the church are dated to the same period. The panel depicting the king (Fig. 2) is probably evidence that William was alive when the mosaics were completed (Vagnoni 2017, 82-84). William II is portrayed next to Christ, who is seated on a throne and wears typical roman dress (the toga and the pallium), with his left-hand holds an open book while with his right one crowns Rex Guilielmus, as indicated by the writing on the wall. The scene is completed with the two angels at the top carrying the labarum and the orb, signs of William’s power. The king received his crown with the same gesture that we see in Roger’s mosaic. In a second portrait, William is shown offering the church to the Virgin (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown (Italian). Roger II crowned by Christ, ca. 1143-1149. Mosaic. Palermo: Church of the Admiral. Source: Flikr

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown (Italian). William II crowned by Christ, ca. 1177-1183. Mosaic. Sicily: Monreale Cathedral. Source: SH Digital Library

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown (Italian). William II offers the church to the virgin, ca. 1177-1183. Mosaic. Sicily: Monreale Cathedral. Source: Smarthistory

The political situation in Sicily was stable when the two mosaics were made: in 1135 Roger II had to remove Lothair II (1075-1137) who had been sent by the Byzantine emperor John Komnenos, but thanks to negotiations Pope Innocent II confirmed the royal title to Roger II and his sons received the investiture. William’s II power was recognised by the most important courts of Europe through his marriage to Joan of England (1165-1199) (Vagnoni 2017, 112).

In the two panels Roger II and William II are crowned by Christ. The scene resembles the byzantine iconography used to reiterate and reinforce the sovereign’s legitimacy by depicting him as God’s minister on earth (Borsook 3-6). The development of this symbolic iconography was especially promoted by the Macedonian dynasty (IX-X century) and emphasises the divine origins of imperial power (Brodbeck 167-168). As a confirmation of the legitimacy of his power, the panel with William’s coronation is located above the throne engaged at the north-eastern crossing pier, near the presbytery. Thanks to the presence of the throne and the series of Judaean kings in the arch soffit overhead, William becomes here the heir of David (Borsook 67-68).

Artist Unknown. Roger II crowned by Christ, c. 1143-1149. Mosaic. Palermo: Church of the Admiral. Source: Flickr

ABOUT THE GARMENTS

Norman kings are depicted wearing a byzantine dress consisting of a long white tunic called divetesion or skaramangion with embroidered cuffs and a loros that envelop their shoulders, their waist and their left forearm (Kiilerich 442-443). In William’s portrait this typical byzantine garment is characterised by a green lining and a rich decoration made of precious stones and pearls. The loros worn by Roger has a similar rich ornament but is lined with a red fabric with rope-like decorations. On their feet they wear a pair of shoes that recall the campagia, usually worn by the emperor. They also wear a crown identified as a Plattenkrone made of gold and encrusted with stones and like the byzantine crown it is characterised by the pendilia (Vagnoni 2017, 94).

The loros was the most important element of the imperial dress. It was essentially a long scarf crossed over the chest, then tightened at the abdomen and the two ends were draped over the left forearm. This bejeweled fabric has an ancient origin that imbues the garment with the idea of triumph and victory as it derives from the trabea triumphalis, a toga worn by Roman consuls (Parani 18-19, 23). According to the De Cerimoniis the loros was worn by the emperor during important religious feast-days and it was chosen by the artists to portray the emperor in the Middle Byzantine period. In the tenth century the loros acquired a new meaning: it commemorated the Christ’s burial and Resurrection. For this reason, Parani states that the loros costume transforms the emperor not only in a divine ruler, but directly into Christ (Parani 24).

As Vagnoni states, some evidence shows that Norman rulers were deliberately depicted in Byzantine imperial robes. For example, the Ordo Coronationis, an important source written during the reign of Roger II, mentions that the king was adorned with a cape. This information is confirmed by the Weltliche Schatzkammer in Vienna, where there is a precious cape made in the Norman court atelier between 1133-1134. Conversely, there aren’t written or material evidences of the real use of the loros, a garment in which the kings were usually depicted (Vagnoni 2011, 51).

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown. Constantine VII crowned by Christ, ca. 954 CE. Ivory plaque; 18.6 x 9.5 cm. Moscow: Pushkin Museum. Source: World History Encyclopedia

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown. Manuel I Komnenos and Maria of Antioch, ca. 1166. Manuscript vat. gr. 1176. Source: Medievalist

The reason why Roger and William II have been represented as byzantine emperors is to connect themselves and their reign with the Byzantines, who controlled the south of the Italian peninsula and Sicily in the previous centuries. But it should be noted that if we compare the clothing of the Norman kings with that of the Byzantines, it is evident that they did not choose a contemporary model but a type that predates the XII century (Vagnoni 2011, 58). In fact, in art depicting the contemporary Byzantine emperor, Manuel I Komennos (Fig. 5), the emperor wore a simplified loros, which instead of being crossed was probably replaced by a sewn garment with a head opening and the train was kept and draped in the same manner (Parani 20-21). Instead, the imperial clothing worn by the two Norman kings can be dated to the X-XI centuries when the Norman reign established itself through the conquest of Reggio Calabria (1060) and Bari (1071) with Robert Guiscard. It is possible to see a close resemblance between the robes on the ivory panel (Fig. 4) depicting the coronation of Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus dated to the 10th century and those of the mosaics (Brodbeck 168).

The Norman kings not only wanted to make a connection between themselves and the earlier Byzantine presence in Italy, but they chose a type of dress that recalls the origin of their reign by showing the continuity from earlier ruler Robert Guiscard to their time.

MOSAICS ON THE CATWALK

For the Fall/Winter 2013-2014 collection, Dolce & Gabbana were inspired by the Monreale mosaics. The Italian duo decided to honor their country and Sicily, the region they come from. Some of the clothes in the collection and the jewelry were clearly inspired by Byzantine art with rich decorations and gold details. Some fabrics have been printed with photos of the original mosaics or have been embroidered on the dresses and enriched with Swarovski crystals (Figs. 6-8).

Fig. 6 - Dolce & Gabbana (Italian). Bustier and Skirt, Fall/Winter 2013-14. Source: Vogue Italia

Fig. 7 - Dolce & Gabbana (Italian). Dress, Fall/Winter 2013-14. Source: Vogue Italia

Fig. 8 - Dolce & Gabbana (Italian). Top, Fall/Winter 2013-14. Source: Vogue Italia

References:

- Borsook, Eve. Messages in Mosaic: The Royal Programmes of Norman Sicily, 1130-1187. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/802800044

- Brodbeck, Sulamith. Le souverain en images dans la Sicile normande in Perspective. Institut National d’Histoire d’Art, 1, (S. 2012): 167-172 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/888825781

- Kiilerich, Bente. Attire and Personal Appearance in Byzantium in Byzantine Culture, Papers from the Conference, “Byzantine days of Istanbul”, ed. Dean Sakel, Ankara, 2014. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/951640691

- Parani, Maria G. Reconstructing the Reality of Images: Byzantine Material Culture and Religious Iconography (11th-15th centuries). Leiden-Boston: Brill, 2003. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/876439541

- Vagnoni, Mirko. Dei gratia rex Sicilie. Scene d’incoronazione divina nell’iconografia regia normanna. Naples: FedOA, 2017. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1028528488

- Vagnoni, Mirko. Problemi di legittimazione regia: Imitatio Byzantii in Il papato e i Normanni. Temporale e spirituale in età normanna, a cura di E. D’Angelo, C. Leonardi, Atti del Convegno di Studi, Ariano Irpino, 2007. Florence: SISMEL, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/776488901