This gold-colored silk afternoon dress with its green bows and ruffles that help to emphasize the back of the silhouette was on trend in 1866, but its coordinating trompe l’oeil jacket was very fashion-forward.

About the Look

T

his green and gold silk afternoon dress features a trompe l’oeil bolero jacket. Trompe l’oeil, a French term for creating a visual illusion, is used in this dress to give the impression of a bolero jacket. This visual detail is created from the use of both silk and braided silk (Fig. 4), a trimming detail that is repeated throughout the dress. The silk and rope are used to create what would be the outline of the jacket, and buttons add to the illusion of a top that would be worn underneath the jacket. The bodice of the dress is cropped and fitted. The sleeves of the dress are edged with the braided rope and bow detail that looks similar to a flower (Fig. 6). These sleeves gradually get wider below the shoulder and are also edged in the braided rope.

The front of the skirt has two layers of ruffles, giving the dress an apron effect. When the gown is viewed in profile, there is a noticeable difference between the fullness in the back and the front (Fig. 1). This prominent fullness of the back of the dress was beginning to emerge as the fashionable silhouette at the time. This fullness is made even more prominent by the detail of the sashes and bows that trail down the back of the gown (Fig. 2). The sashes are edged with fringe (Fig. 5) that would give the dress a lot of movement. The sash detailing is also used on the top half of the dress, connected by a bow that is similar to those used on the sleeves. The label (Fig. 3) in the dress states that it was made by Maison Clément, located at 8 Place de la Madeleine in Paris.

Very little information is known about Maison Clément or Delion Lericheux (also named on the label), but one can assume that s/he was French couturier in Paris during the 19th century.

Fig. 1 - Maison Clément (French). Afternoon dress, ca. 1866. Silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.48.62a, b. Gift of Mary Chippendale, 1948. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 2 - Maison Clément (French). Afternoon dress, ca. 1866. Silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.48.62a, b. Gift of Mary Chippendale, 1948. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 3 - Maison Clément (French). Afternoon dress (label), ca. 1866. Silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.48.62a, b. Gift of Mary Chippendale, 1948. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 4 - Maison Clément (French). Afternoon dress (detail), ca. 1866. Silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.48.62a, b. Gift of Mary Chippendale, 1948. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 5 - Maison Clément (French). Afternoon dress (detail), ca. 1866. Silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.48.62a, b. Gift of Mary Chippendale, 1948. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 6 - Maison Clément (French). Afternoon dress (detail), ca. 1866. Silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.48.62a, b. Gift of Mary Chippendale, 1948. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Afternoon dress, 1866. Golden yellow silk with green trimmings. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.48.62a, b. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

About the context

T

his look is a good representation of the beginning of the shift in silhouette during the 1860s. During this time, it became more fashionable to have a skirt that was flat in the front and fuller in the back. Crinolines were still used at the time to create this shape. The Metropolitan Museum of Art says about this dress:

“The devices of bolero and apron differentiated sectors within the dress and emphasized the high placement of the waist, while crinoline hoop shifted to the back to make the great shape of the skirt mountainously prominent.”

The long train of the dress gives further emphasis to the fullness of the rear of the skirt. Long trains can be seen in various fashion plates from 1866 (Fig. 7). The bow and sash detail on the back of the dress add more volume and length to the dress, a detail that can also be seen in a dress by Depret from 1867 (Fig. 8). The narrow waist of the dress helped to accentuate the length and fullness of the skirt’s train. In a column titled “Chit Chat Upon New York and Philadelphia Fashions for February,“ Godey’s Magazine said: “Skirts are all made with a train and very full at the hem, the fullness, however, decreasing at the hips” (199).

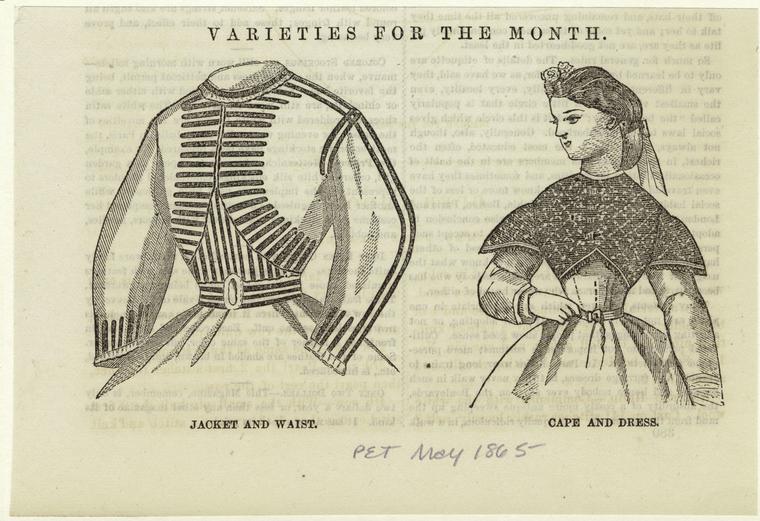

Even though this dress does not actually have a bolero jacket, the trimming details give the effect of one. The bolero, a short open-fronted jacket, is a style very similar to the chaquetilla jacket worn by Spanish bullfighters (Fig. 9). The bolero style can be found in fashion plates from 1866, which feature cropped jackets with an open front (Fig. 10).

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown (French). La Toilette de Paris, 1866. Ink on paper. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17509853. Gift of Woodman Thompson. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art Digital Collections

Fig. 8 - Depret (French). Dress, ca. 1867. Silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.62.35.1a–c. Gift of Miss Elizabeth R. Hooker, 1962. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 9 - Édouard Manet (French, 1832–1883). A Matador, 1866-67. Oil on canvas; 171.1 x 113 cm (67 3/8 x 44 1/2 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 29.100.52. H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 10 - Artist unknown (American). Varieties for the Month: Jacket and Waist; Cape and dress, May 1865. Ink on paper; 10 x 15 cm (4 x 5 3/4 in). New York: New York Public Library, NYPL catalog ID (B-number): b17566451. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection. Source: New York Public Library Digital Collections

During this time there was also an emphasis on the size and style of sleeves. This dress has sleeves with a small “puff” towards the end of the shoulder. Godey’s Magazine mentions sleeve size and their “puff” twice. First, in their column “Chit Chat Upon New York and Philadelphia Fashions for January,” they said: “Some of the new sleeves are almost tight from the wrist to the elbow, and then puff out very much in the old leg of mutton style” (104).

In a column titled “Chitchat Upon New York and Philadelphia Fashions for October,” Godey’s Magazine wrote: “Sleeves are of the coat shape, some varied with large loose puff at the top sewed into a straight band” (367). The sleeve of the afternoon dress incorporates both of these trends. The sleeves take on more of a coat shape, adding to the effect of the trompe l’oeil. The sleeve also gradually gets larger as it goes from the wrist to the shoulder, the puff of fabric adding to this effect.

In their column “Fashions for February,” Peterson’s Magazine also said on sleeves: “Sleeves are trimmed from the wrist to the shoulder, sometimes the trimmings winds around the arm in a spiral manner” (162). When looked at closely, the edges of the dress sleeves are trimmed with a bow and the rope trim that is used throughout the dress. Sleeve trimmings in a similar style can be found in various fashion plates from 1866 (Figs. 11, 12).

This dress could, in ways, be considered ahead of its time because of the trompe l’oeil jacket design. The use of bows and fringe became much more popular in the following year, as demonstrated by the designer Depret (Fig. 8). The bolero jacket was popular during this time, but the use of a trompe l’oeil feature was quite uncommon during 1866 and was not widely featured in fashion magazines from the time.

Fig. 11 - Artist unknown (French). Musée Des Familles, 1866. Ink on paper. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17509853. Gift of Woodman Thompson. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art Digital Collections

Fig. 12 - Artist unknown (French). Petit Courrier Des Dames, November 1866. Ink on paper. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17509853. Gift of Mary P. Hayden. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art Digital Collections

References:

- “Afternoon Dress”. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed April 2017. http://metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/85417

- Burnham, Helen. “Changing Silhouettes.” In Impressionism, Fashion and Modernity, ed. Gloria Groom, 255. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/794814340

- “Chitchat Upon New York and Philadelphia Fashions for February,” Godey’s Magazine 72 (February 1866): 199. Godey’s Magazine

- “Chitchat Upon New York and Philadelphia Fashions for January,” Godey’s Magazine 72 (January 1866): 104. Godey’s Magazine

- “Chitchat Upon New York and Philadelphia Fashions for October,” Godey’s Magazine 73 (October 1866): 367. Godey’s Magazine

- Edwards, Lydia. How to Read a Dress: A Guide to Changing Fashion from the 16th to the 20th Century. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/988370049.

- “Fashions for February,” Peterson’s Magazine 49-50 (February 1866): 162. Peterson’s Magazine

- “Traje De Luces.” Wikipedia. Accessed June 30, 2016. Wikipedia