This dignified portrait by Diego Velázquez depicts his enslaved Black assistant, Juan de Pareja, who was a skilled artist in his own right.

About the Portrait

The man in this portrait, Juan de Pareja, was a skilled Spanish artist of African descent. He was enslaved by its artist, Diego Velázquez, leading to a portrait that artist Julie Mehretu has described as ‘haunting’ (Met).

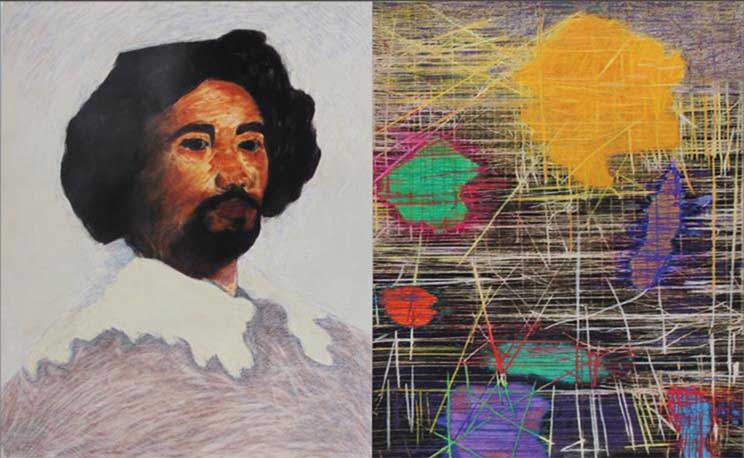

Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (Fig. 1) is considered to be one of the most important artists of the seventeenth century (Sánchez). He was Spanish of Portuguese descent and was born in Seville in 1599. From 1623 he served as the court painter to the king of Spain, a prestigious position, and created many portraits of royalty and courtiers. His early style was naturalistic with a fondness for dramatic shadows and contrasts (Fig. 2). His later work was influenced by other masters like Rubens (Dutch) and Titian (Italian) and he “developed a uniquely personal style characterized by very loose, expressive brushwork” (Sánchez). A close look at the edging on de Pareja’s white collar shows the loose but delicate way that the lace is painted – it is not detailed, but merely suggested. Velázquez treated many details of costume like this, so while his portraits are beautiful examples of clothing, the precise characteristics are often lost (Sánchez). He executed this portrait while he and de Pareja were in Italy to paint Pope Innocent X in 1650; as the story goes, the window of time to paint the Pope was small and Velázquez decided to practice painting from life on his enslaved assistant (Rousseau 3). Velázquez died in 1660 after being made a Knight of Santiago (Sánchez).

Juan de Pareja was born to an African mother, Zulema, and a Spanish father, Juan, in Seville in 1606 (Salomon). His status before he became Velázquez’s possession is unknown. He was, however, registered as a painter in Seville before he became Velázquez’s assistant in the early 1630s, which was not usually a position an enslaved person could hold (Fahy 23). (There is some debate as to whether the record actually refers to a different Juan de Pareja.) He became equally adept at painting grand portraits (Fig. 3) and large religious scenes (Fig. 4 is a detail) (Domenech). Velázquez eventually freed him for unknown reasons in 1654, and de Pareja continued to paint until his death around 1670 (Salomon, Domenech).

Juan de Pareja’s portrait is unique in two respects: it is one of the few from this era for which we have evidence of public acclaim, and it is the earliest Spanish portrait that we know of that depicts a named Black sitter. Black Africans and Europeans had a steady presence in southern countries like Spain and Italy from the medieval period, most but not all of which was driven by the slave trade (Kaufmann 4, Lowe 13). Respectful and realistic portraits of Black people exist in European portraiture back to Mostaert in the early sixteenth century, and in genre scenes and other art the date is much earlier. However, most of these portraits are of unnamed subjects.

While Juan de Pareja is far from the only Black European to have been a skilled artist during the Renaissance, he is more unusual for having a serious portrait by an artist considered to be an Old Master (Lowe 14). While others like Rembrandt van Rijn painted and sketched a number of Black people, few are ever named (Kolfin 10). Not only do we have de Pareja as painted by Velázquez, but a self-portrait also exists, as de Pareja added himself into a painting in 1661 (Fig. 4, left) in the same manner that Velázquez painted himself into the famous Las Meninas (Fig. 5). This means that while de Pareja probably did not have any control over how Velázquez depicted him, he was eventually able to paint himself as he wished to be known and have the canvas survive the centuries.

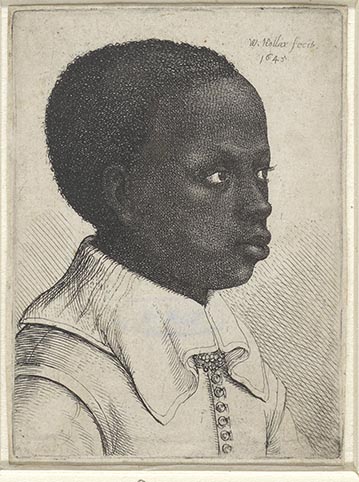

Juan de Pareja is certainly not the only Black portraitist to have existed during this period, but we are lucky to both know his story and have multiple depictions of him (Spicer 83). The unnamed artist in figure 6 may have been a skilled painter, but not to the point of curating his own image: he wears a metal collar and is dressed in clothing a century out of date. Both are entrenched tropes for Black people in Western art, and a sure sign of enslavement or servitude (Waterfield 141, Lowe 14). While the scene appears to be in the manner of other self-portraits, we would expect that – much like de Pareja – an artist’s self-portrait would never be so caricatural, so this is likely by a white painter. In comparison, de Pareja is dressed in up-to-date clothing, and nothing about his appearance in either of his portraits suggests that he is or was enslaved.

De Pareja’s features are treated with delicacy, and all signs point to this portrait being entirely from life. There is even what may be a splotch of paint on his elbow (though it has previously been interpreted as a torn sleeve) as if he has pulled his more formal jerkin and cloak on over his work clothes (Rousseau 4). The soft atmosphere of the painting is typical for Velázquez, and if not for the cruel irony in painting his enslaved man so respectfully, this portrait is otherwise as graceful and lovely as those he executed of kings and princesses (Met).

This portrait of Juan de Pareja was exhibited at the Pantheon in Italy after it was completed in 1650, and met with acclaim. Historian Antonio Palomino y Velasco published an account of the event in 1715 and wrote that the painting was:

“generally applauded by all the painters from different countries who said that the other pictures in the show were art but this alone was ‘truth’. As a result, Velázquez was elected to the Roman Academy.” (Rousseau 3-4)

Fig. 1 - Diego Velázquez (Spanish, 1599-1660). Self-portrait, ca. 1640. Oil on canvas; 45 x 38 cm. Museu de Belles Arts de València, 572. Source: MdBAV

Fig. 2 - Diego Velázquez (Spanish, 1599-1660). Kitchen Scene, 1618/20. Oil on canvas; 55.9 × 104.2 cm (21 7/8 × 41 1/8 in). Art Institute of Chicago, 1935.380. Robert A. Waller Memorial Fund. Source: AIC

Fig. 3 - Juan de Pareja (Spanish, 1606-1670). Portrait of the Commander of the Order of Sant Iago, 1630s. Oil on canvas; 197 x 109 cm. St. Petersburg: The State Hermitage, GE-324. Entered the Hermitage in 1845; transferred according to the will of D.P. Tatishcheva. Source: Hermitage

Fig. 4 - Juan de Pareja (Spanish, c.1606-1670). Detail from The Calling of Saint Matthew, 1661. Oil on canvas; 225 x 325 cm. Madrid: Museo del Prado, P001041. Source: Prado

Fig. 5 - Diego Velázquez (Spanish, 1599-1660). Detail of Las Meninas, 1656. Oil on canvas; 320.5 x 281.5 cm. Madrid: Museo del Prado, P001174. Source: Prado

Fig. 6 - Artist unknown (Possibly Brazilian). Black Artist Completing a Portrait of Maria Anna of Austria, Queen of Portugal (1683-1754), First quarter of the 18th century. London: Carlton Hobbs, 9897. Source: Carlton Hobbs

Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (Spanish, 1599–1660). Juan de Pareja, 1650. Oil on canvas; 81.3 x 69.9 cm (32 x 27 1/2 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1971.86. Purchase, Fletcher and Rogers Funds, and Bequest of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot (1876-1967), by exchange, supplemented by gifts from friends of the Museum, 1971. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

About the Fashion

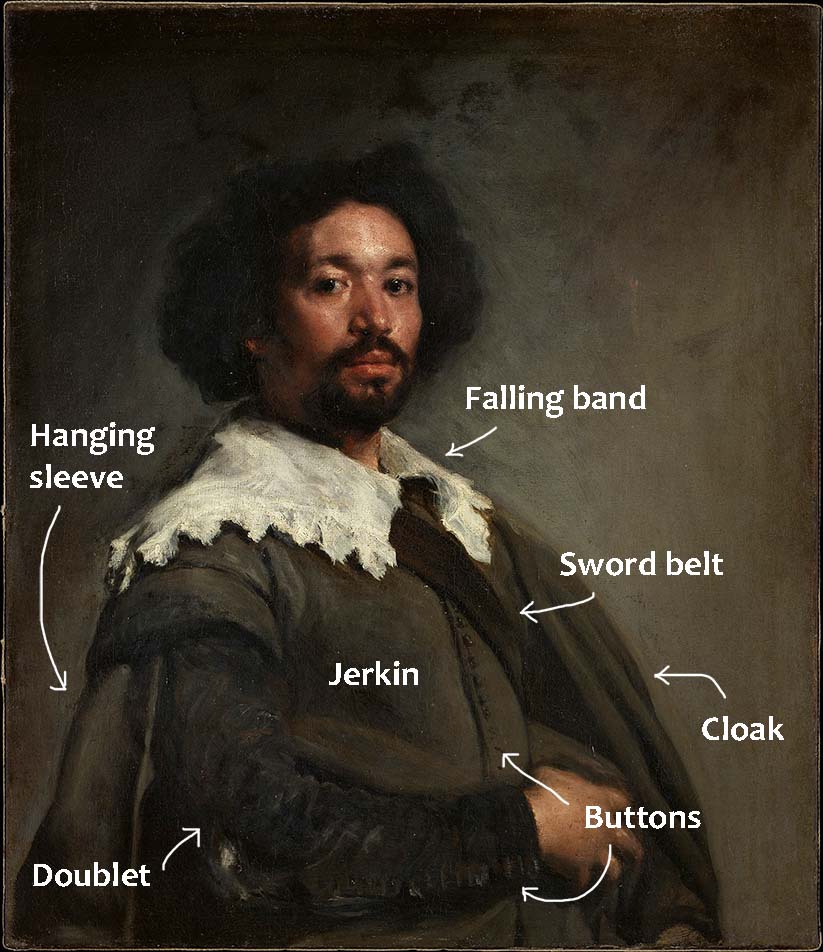

Juan de Pareja’s clothing in this portrait is a subdued palette of dark greys and blacks with a pop of white at the neckline. His visible garments include a doublet, a jerkin, a cloak or cape, a sword belt, and a collar.

Black ensembles were fashionable in most of Europe for the first half of the sixteenth century; variation in hairstyle, collar width, and silhouette are often the only ways to date a portrait. As Valerie Steele describes in her 2007 book The Black Dress:

“More typical of the 16th century was the fashion for dressing in all black, except for an accent of white at collar and cuffs. Both men and women wore black clothing, its sober elegance enlivened by dramatic white ruffs that framed the face.… With the rise of French power in the seventeenth century, the fashion for Spanish black went into decline, except in Spain, where women like the Duchess of Alba continue to wear it.” (n.p.)

In the 1650s, doublet waists were newly loose and the most fashionable of men left their buttons open at center front and on sleeves in order to expose their fine white linen shirts (Fig. 7) (Ribeiro 30). In most of Europe, the wide white falling bands (collars) of the 1630s and 1640s had finally shrunk. While Spain had led European fashion in the last part of the 16th century, the country’s conservatism led to it lagging behind mainstream fashion for much of the 17th century (Tortora 204).

De Pareja’s black doublet is visible only on his arm, and has a line of buttons towards the cuff. It may be made of wool or silk – possibly cheap wool, given his enslavement – and is probably a sensible garment that he could work in (Staples 413). His lack of white linen cuffs (Fig. 8) is odd for such a formal portrait, but since it was painted from life, perhaps he either had them off for working or never had any on in the first place. For the same reason, it is possible that the elaborate falling band was quickly added to his outfit for Velázquez to practice rendering lace. Why would an enslaved assistant be wearing such a grand lace collar when he did not even have a pair of cuffs?

His gray jerkin (jacket) has winged shoulders, a line of buttons down the center front, and hanging sleeves. Much like the doublet, it is probably made of wool, but might be a plain silk. The hanging sleeves are outdated by this time in other countries; in The Dictionary of Fashion History (2010), Valerie Cumming, C. W. Cunnington, and P. E. Cunnington describe:

“Period: ca. 1560-1640. Sham or false hanging sleeves were worn by both sexes. Men’s garments had pendant streamers attached to the back of the arm-hole; the remains of a true hanging sleeve had become nearly ornamental. Worn sometimes with jerkins.” (100)

The Spanish did continue to use hanging sleeves fashionably after 1640 (Fig. 9) but any man who kept up with the rest of the continent had done away with them (Fig. 8). Because of the position of de Pareja’s arm, it is impossible to tell where the waist of his jerkin is positioned, and whether it is more suitable for the 1640s or if it is up to date. An extant ensemble made for the Spanish court in 1655 can be seen in figure 10, showing what the Spanish considered a fashionable waistline and silhouette.

De Pareja also sports a matching dark grey cloak or coat that is slung across one shoulder in a fashionable manner; the slightly later courtier in figure 11 wears one similarly (Tortora 208). The strap across Juan de Pareja’s chest is likely a sword belt like the one on Adrián Pulido Pareja in figure 9 – not something an artist would normally have carried. Along with the falling band, the cloak and belt may be costume pieces and not his everyday clothing.

De Pareja’s falling band is so broad as to almost be a relic of the 1630s. Compare it with the collars in figures 7, 8, and 11, all much small and either on Dutch or fashion-forward Spanish men. Collars are another aspect in which Spain lagged behind; notice the rather broad falling bands worn by the men in figures 9 and 12, painted around the same time as de Pareja. White linen collars were stiffly starched and sometimes even wired when worn by the elite; they would never have stood up quite so well on the men in figures 8 & 11 otherwise. However, they were worn without starching by the middle and working classes; see the boy in figure 13, whose falling band is nicely hemmed and pleated and yet droops around the standing collar of his doublet.

Compare this clothing with Pareja’s 1661 ensemble in figure 4. While it is from a decade later, we see that Pareja engages in the fashionable shirt exposure (in which cuffs on the doublet are unnecessary; see figure 7) and sports a much more modest and ordinary collar. It seems likely that the one he wears in the 1650 portrait was an accessory added by Velázquez.

His hairstyle is also somewhat dated; while not unfashionable in other countries, it is not the longer, sleeker style that men were beginning to seek in Spain (Figs. 11 & 14). It is, however, similar to the casual style of the man in figure 12 is wearing, and appropriate enough for the “somewhat shorter and fuller [English] hairstyle of the early 1650s” (Ribeiro 116). His mustache and beard, too, are hardly cutting-edge style – the mustache of choice in the 1650s was the thin, sharp one seen in figures 11 and 14, and beards were often isolated to the chin area (Stainton 126). His naturally curly hair was probably perfectly in fashion in the 1640s, when styles were more evenly concentrated around the top and sides of the head (Ribeiro 116).

Aside from the ostentatious collar, his simple clothing and casual hairstyle indicate his position as a working man. There is no decoration on the fabric and his hair – the easiest aspect of fashion to keep up with – is in an older style. The hanging sleeves on his jerkin could indicate an old set of clothing, but may just as much be the product of lagging Spanish fashion. He is dressed well for a Spanish working-class man, but less fashionably than his enslaver, who can be seen with an exposed shirt in figure 5.

Compare de Pareja’s ensemble to the artist Bartolomé Esteban Murillo’s self-portrait from about the same time (Fig. 14). Murillo also wears Spanish black, but sports flamboyant paned sleeves that expose his shirt along with a small upright collar (golilla) and very fashionable hair and moustache (Cumming 94). Murillo was a free man able to depict himself in the way that he desired; de Pareja may have chosen similarly if he had been the agent of his own portrait in 1650. And indeed, in 1661, he made similar choices – paned sleeves and a pointed moustache. Whether or not he actually sported them in real life, he was only able to paint himself wearing such fashions after he was manumitted (freed). The 1650 portrait is touted as being “from life” and indeed reveals Velázquez’s both literal and figurative control over Juan de Pareja and his image.

Fig. 7 - Frans Hals (Dutch, 1582-1666). Portrait of a Man, 1651-2. Oil on canvas; 110.5 x 86.4 cm (43 1/2 x 34 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 91.26.9. Marquand Collection, Gift of Henry G. Marquand, 1890. Source: MMA

Fig. 8 - Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (attr.) (Spanish, 1617–1682). Portrait of an unknown man, mid 1650s. Oil on canvas; 121 x 99 cm. London: The Wellington Collection, Apsley House, WM.1546-1948. Source: ArtUK

Fig. 9 - Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo (Spanish, 1612–1667). Retrato de don Adrián Pulido Pareja, ca. 1647-50. Oil on canvas; 203.8 x 114.3 cm (80.2 x 45 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NG1315. Source: NPG

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown (Spanish). Nils Brahe's Spanish costume, 1655. Skokloster Castle, Livrustkammaren, T 10547. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 11 - Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (Spanish, 1618-1682). Portrait de Iñigo Melchor Fernández de Velasco, 1658. Oil on canvas; 208 x 138 cm. Paris: Louvre, R.F. 1985-27. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 12 - Artist unknown (Spanish). Portrait of a young man, ca. 1650. Oil on canvas; 57 × 42 cm. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, E3-1976. Everard Studley Miller Bequest, 1976. Source: NGV

Fig. 13 - Wenceslaus Hollar (Bohemian, 1607-1677). Portret van een zwarte jongen, 1645. Etching on paper; 8 x 5.9 cm. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-11.589. Source: Rijksmuseum

Fig. 14 - Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (Spanish, 1617−1682). Self-Portrait, ca. 1650-55. Oil on canvas; 107 x 77.5 cm (42 1/8 x 30 1/2 in). New York: The Frick, 2014.1.01. Source: Frick

Its Legacy

Juan de Pareja’s portrait has inspired many artists over the centuries. Because it was done by such a famous and revered painter (and is such a prominent public art museum), it has received far more attention than other portraits of Black sitters from this period. It has been copied many, many times and often the space in front of it at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is occupied by new artists testing their skills at the easel (Fig. 15).

Perhaps the most famous painting inspired by it is surrealist artist Salvador Dalí’s, done in 1960 (Fig. 16); Pareja’s silohuette appears on the right side of the canvas, with the bright white spot serving as his eye.

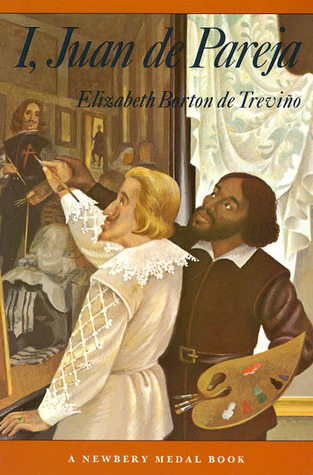

Only a few years later, Elizabeth Borton de Treviño published her semi-fictionalized biography I, Juan de Pareja (1965), complete with a cover showing de Pareja guiding a blond Velázquez in adding the Knight of Santiago symbol on his jerkin in Las Meninas (Fig. 17); the book, aimed at children, won a Newbery Medal.

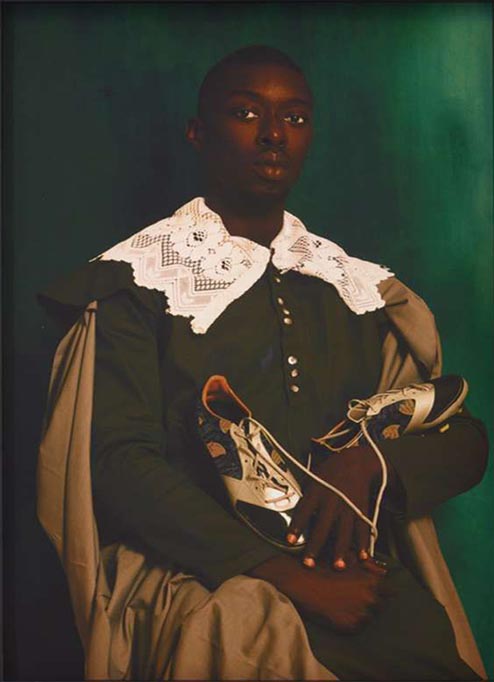

More recently, Chicano artist Rupert García dedicated a mixed media piece to de Pareja (Fig. 18). American artist Kathleen Giljie repainted the portrait to feature Black American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat (Fig. 19) and Senegalese artist Omar Victor Diop reimagined himself as de Pareja through the lens of soccer (Fig. 20).

Fig. 15 - Artist unknown. Man painting a copy of Velázquez' portrait of Juan de Pareja, Before 2020. Photograph. Source: Mapio

Fig. 16 - Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989). Portrait of Juan de Pareja, the Assistant to Velázquez, 1960. Oil on canvas; 74.3 x 88.27 cm (29 1/4 x 34 3/4 in). Minneapolis Institute of Art, 84.5. Source: MIA

Fig. 17 - Artist unknown. I, Juan de Pareja, 1965. Source: Goodreads

Fig. 18 - Rupert García (American, 1941-present). For Juan de Pareja, 2010. Mixed media on paper; (47.5 x 76.25 in). Source: Magnolia Editions

Fig. 19 - Kathleen Gilje (American, 1945-present). Basquiat as Velazquez’s Portrait of Juan de Pareja, 2011. Oil on linen; (32 ¼ x 28 ¾ in). Source: Gilje

Fig. 20 - Omar Victor Diop (Senegalese). Juan de Pareja (Diaspora), 2014. Pigment inkjet print on paper; 60 x 40 cm. Paris: Fondation Louis Vuitton. Source: FLV

References:

- Cumming, Valerie, Phillis Cunnington, and C. Willett Cunnington. The Dictionary of Fashion History. Oxford: Berg, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/751449764

- Domenech, Fernando Benito. “Pareja, Juan de.” Grove Art Online.

2003; Accessed 5 Aug. 2020. Oxford Art Online - Kaufmann, Miranda. Black Tudors: The Untold Story. London, England : Oneworld Publications, 2017. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1083265546

- Kolfin, Elmer. “Black by Rembrandt.” In Black in Rembrandt’s Time. Elmer Kolfin & Epco Runia, eds. Zwolle: WBOOKS, 2020. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1137196444

- Lowe, Kate. “The Lives of African Slaves and People of African Descent in Renaissance Europe.” In Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe. Joaneath Spicer, Kate Lowe, and Natalie Zemon Davis, eds. Baltimore: The Walters Art Museum, 2012. Worldcat | Available in full online!

- Met. “Julie Mehretu on Velázquez’s Juan de Pareja.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Artist Project. Accessed 4 August 2020. www.artistproject.metmuseum.org/5/julie-mehretu/

- Ribeiro, Aileen, and Valerie Cumming. The Visual History of Costume. New York: Costume & Fashion Press, 1997. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/38202681

- Rousseau, Theodore, Everett Fahy, and Hubertus von Sonnenburg. Juan De Pareja by Diego Velázquez. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1970. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/4378302

- Salomon, Xavier F. and Keith Christiansen. “Catalogue Entry: Juan de Pareja.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019. Accessed 5 August 2020. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437869

- Sánchez, Alfonso E. Pérez. “Velázquez, Diego.” Grove Art Online.

2003; Accessed 5 Aug. 2020. Oxford Art Online - Spicer, Joaneath. “Free Men and Women of African Ancestry in Renaissance Europe.” In Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe. Kate Lowe and Natalie Zemon Davis, eds. Baltimore: The Walters Art Museum, 2012. Worldcat | Available in full online!

- Stainton, Lindsay, and Christopher White. Drawing in England from Hilliard to Hogarth. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/300035683

- Staples, Kathleen, and Madelyn Shaw. Clothing Through American History: The British Colonial Era. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/879022531

- Steele, Valerie. The Black Dress. New York: Collins Design, 2007. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/757101055 | Google Books

- Waterfield, Giles. “Black Servants.” In Below Stairs: 400 Years of Servants’ Portraits. London: National Portrait Gallery Publ, 2003. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/834455426