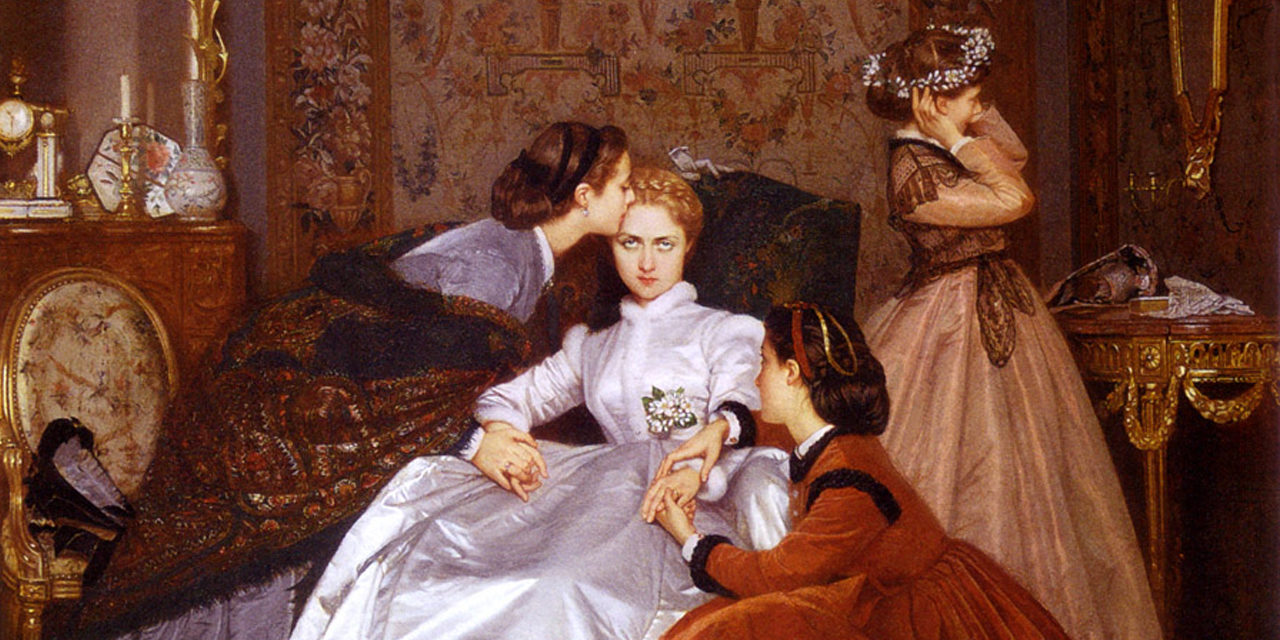

In The Hesitant Fiancée, Auguste Toulmouche steps away from his usual depiction of beautiful yet idle women Emile Zola described as “Toulmouche’s delicious dolls.” He refines his style by painting a more complex subject–one of an arranged marriage that the bride clearly rebels against, as evidenced by the subject’s direct gaze. Despite the shift of the subject matter, Toulmouche keeps to his standard of painting lavish gowns and luxurious backdrops.

About the Artwork

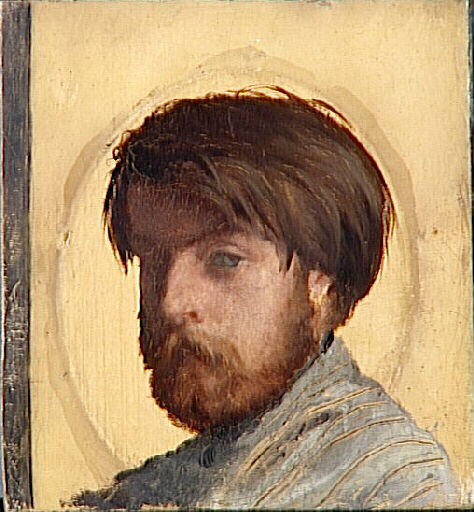

On September 21, 1829, Auguste Toulmouche (Fig. 1) was born in Nantes, France. The few known facts about Toulmouche’s artistic background are that in 1841, he was studying design with another local sculptor, Amedo Rene Menard. Then in 1844, he was learning painting from Biron, a portraitist who taught in Nantes. When he turned 17, Auguste Toulmouche left for Paris in 1846 after completing his rudimentary art education. It was in Paris where he entered the studio of Charles Gleyre, a Swiss painter who was later known for his association with the future Impressionist artists Monet and Renoir. Under Gleyre’s guidance, Toulmouche learned to paint in the Académie des Beaux-Arts style that dominated French art in the mid-19th century. By 1848, at only nineteen years old, Toulmouche was ready for his Salon debut (Whitmore).

Fig. 1 - Jean-Louis Hamon (French, 1821-1874). Auguste Toulmouche, 19th Century. Oil painting on wood; 43.18 x 39.37 cm (17 x 15.5 in). Dijon, France: Magnin National Museum. Source: Wikipedia

Toulmouche was considered a realist genre painter. Dr. Janet Whitmore in her biography on Toulmouche quotes critic Emile Zola who referred to Toulmouche’s painted women as “Toulmouche’s delicious dolls” [délicieuses poupées de Toulmouche] (Whitmore). He was best known for his depictions of idle beautiful women dressed in sumptuous fabrics, set against backdrops of equally luxurious interiors. This style of painting was considered very fashionable during the 19th century. Toulmouche was considered a success, and his paintings were generally well-received. In 1852, he won a third class medal, and in 1861 he won a second class medal. In 1870, he was awarded the French Legion of Honor (Whitmore).

According to Whitmore:

“During the 1860s, Toulmouche refined his style, and began exploring more complex compositional structures. Works such as The Hesitant Fiancée, 1866, demonstrates a new confidence in the intricate composition of four women who attempt to persuade the reluctant (and gorgeously dressed) bride to overcome her fears.”

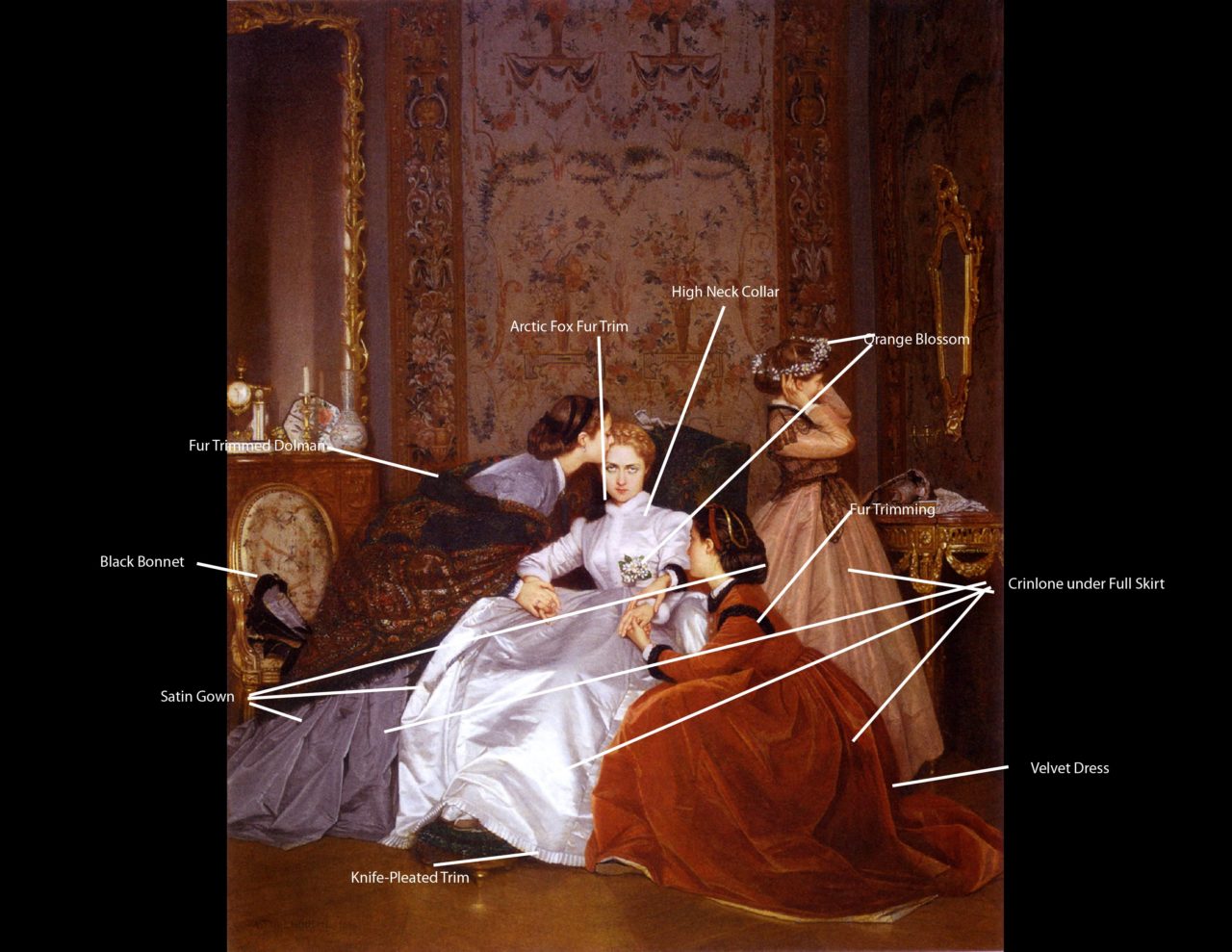

There is little information published about The Hesitant Fiancée, but the subject depicted is quite clear. A reluctant bride, presumably coming from an affluent family as evidenced by her rather opulent bridal dress, sits in a parlor room before the wedding ceremony. In true Toulmouche style, all the women in the painting are dressed lavishly. The woman to the left of the bride in a silk grey dress with a fur-trimmed brown dolman, and the women to the right wears a burnt orange velvet fur-trimmed dress. The textiles in the background are no less carefully rendered.

Despite the magnificent play of color and texture, the most striking aspect of this painting is the bride’s direct gaze at the viewer. Her focus is clear and despite the fact that she is comforted by the two women, she reacts to neither gesture. One is holding her hand; while the other with the shawl, who seemingly just arrived, is kissing her on the forehead. She does not respond to the sentimentality of the gestures and her gaze is defiant. A demonstration of resistance to her dilemma – that of an arranged marriage, a common occurrence during the 19th century.

The bride is juxtaposed by the young girl in the background, who at her tender age and naïveté, still considers marriage as a future dream. She tries on the bride’s flower crown, dreamily imagining her own future wedding.

According to Sotheby’s, The Hesitant Fiancée was possibly exhibited in the Paris Salon of 1866 (as no. 185) and also at the Exposition Universelle of 1867 in Paris (as no. 591).

About the Fashion

The bride is wearing a relatively minimal dress despite the grandeur of the event. She is in a high-neck gown decorated by a downy white fur trim that goes around her neck, down the center front of her bodice, around her armholes and her wrists. The hem of her dress is then decorated with a strip of knife-pleated trim. Despite the simplicity, the gown is no less opulent because of the striking color of white and the shine of the silk fabric. More elaborately trimmed gowns would become fashionable only a few years later, as evidenced by the 1868 photograph of Adelina Patti’s wedding to Marquis Henri de Caux (Fig. 2).

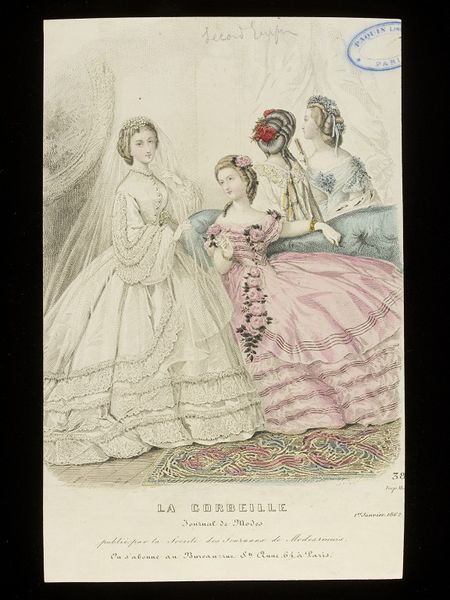

The slim waist and full-skirted silhouette worn by the women in the painting was in vogue during the 1860s (Fig. 3). The full skirt is achieved through the use of a crinoline. According to Jane Ashelford in her book The Art of Dress: Clothes and Society 1500-1914:

“During the 1860s the fashion rules for women allowed the crinoline to change its shape, becoming flatter at the front and then shrinking to a half-crinoline with half hoops at the back. The fullness of the skirt was thus concentrated behind…” (221)

As for the fur trim decorating the bride’s dress, it has a similar look to an 1885 dolman (Fig. 4) which Lucy Johnston describes in her book, Nineteenth-Century Fashion in Detail:

“The neck and fronts, cuffs and hems are edged with wide bands of white arctic fox (Canis lagopus) and deep fringes of chenille trimming. Arctic fox was an expensive and luxurious fur which would have been trapped in the wild, most likely in northern Canada, and imported through London.” (214)

During the 19th century, the bride’s dress design gives an important insight into the century’s customs and social convention. According to the introduction written by JoAnne Olian in Wedding Fashions 1862-1912: 380 Costume Designs from La Mode Illustrée:

“Dress was never more clearly one of the most visible signs of “correctness” and “suitability” so valued by nineteenth-century society, than in the bridal gown.” (iv)

The bridal gown can also be customized, as one can note on the wedding ensemble from 1868 (Fig. 5), in which the the bride chose to trim it with black in order to follow the societal custom for mourning to honor those who died during the civil war (Met).

The color is also notable as brides of social standing tended to wear white, ivory or cream. According to Johnston in her description of an 1865 bridal gown in her book, Nineteenth-Century Fashion in Detail:

“The fashion for white wedding dresses started in the mid-eighteenth century, although most people were married in coloured gowns. By the early nineteenth century more and more women opted for white as it implied purity, cleanliness and social refinement. The less well off or more practically minded opted for pale blue, dove grey or fawn, which they could wear for special occasions long after the event.” (86)

While it was fashionable to have the a bridal gown of white and ivory, as Johnston notes, colored wedding ensembles were also acceptable (Fig. 6). In contrast to the white gown of the bride, the other women in the painting are dressed in colored satins, which were considered fashionable according to “Chitchat upon New York and Philadelphia Fashions for December” in Godey’s Lady’s Books and Magazine (1866):

“Satins will be very much worn: they are of very elegant quality, and rich shades such as crimson, Magenta, blue, green, with the softer shades of mode.” (548)

Focusing on the woman kissing the bride’s forehead, her clothing is within the societal norms of the 1860s with the high collar and the fuller skirt. Her gown is of a bluish-grey tone silk satin material, and her dolman has an exquisite pattern achieved either through embroidery or jacquard material. The dolman is also decorated with either a sumptuous marabou feather or fur trim. This outfit has a similar look to Monet’s Camille from 1866 (Fig. 7) with the fur-trimmed dolman and full skirt.

The other woman in the painting, the one holding the bride’s hand, is dressed in a burnt orange satin/velvet high neck gown. Her dress is decorated similarly to the other two women, with fur strips that wrap around her neck, armholes and wrists.

As for the younger girl in the background, she is dressed in an almost dusty blush-colored gown of either duchess silk satin or taffeta. She is the only one whose dress is devoid of the fur trim, but her gown is still decorated with a darker-colored shawl constructed with a black-trimmed neckline.

As for accessories, the bride herself has the customary orange blossom trim on her gown and on her flower wreath, which the younger girl is trying on. The bride’s hair is in a simple up-do with a single braid going across her hair at the front.

The other women’s hair are also in simple braided up-dos that are decorated by ribbons. The woman with the dolman has clearly just arrived, evidenced by her accessories, from the carelessly tossed bonnet on the chair to her half-gloved hands.

Fig. 2 - Southwell Brothers (British). Adelina Patti's wedding to Marquis Henri de Caux, July 29, 1868. Sepia photograph on paper; 5.9 x 10 cm (2.3 x 4 in). London: Victoria and Albert Museum, S.138:223-2007. Bequeathed by Guy Little. Source: Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (American). Wedding Ensemble Front, 1864. Silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.52.10.2a–f. Gift of Mrs. J. Chester Chamberlain, 1952. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 4 - Emile Pingat (French). Jacket, 1885. Silk voided velvet, white arctic fox and silk chenille fringe, lined with machine-quilted satin. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.64-1976. Given by Mrs G. T. Morton. Source: Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig. 5 - Designer unknown (American). Wedding Ensemble, 1866. Silk, wool, linen, leather. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.53.68.1a–e. Gift of Mrs. Francis Howard and Mrs. Avery Robinson, 1953. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (American). Wedding dress, 1868. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.52.29.1a–c. Gift of Mrs. Ward Burgess, 1952. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 7 - Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926). Camille, 1866. Oil on canvas; 231 x 151 cm (91 x 59 in). Bremen: Kunsthalle Bremen. Source: Kunsthalle Bremen

Fig. 8 - Heloïse Leloir (French, 1819–1873). La Corbeille, January 1, 1862. Hand-colored engraving. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, E.22396:535-1957. Given by the House of Worth. Source: Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig. 9 - Adèle Anaïs Toudouze (French, 1822–1899). Magasin des demoiselles, March 25, 1861. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, E.22396:222-1957. Given by the House of Worth. Source: Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig. 10 - Artist unknown. The London and Paris Ladies' Magazine of Fashion, August 1861. Hand-colored engraving. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, E.594-1967. Given by Mr F. L. Banyard. Source: Victoria and Albert Museum

The women depicted in Toulmouche’s painting are fashionable as evidenced by the fashion plates and wedding ensembles of that period–from the silhouette of a small fitted waist and a bell skirt (Fig. 8), to the fashionable high neck collar (Fig. 9), to the minimal pleated trimming at the hem (Fig. 10). An 1863 plate from Les Modes Parisiennes (Fig. 12) shows a red gown that is similar in look to what the women are wearing in Toulmouche’s painting–from the silhouette, to the decoration of the fur trim around the neck, the armholes, and the cuff–showing the look to be not only fashionable, but also somewhat classic.

Fig. 12 - Artist unknown. Les Modes Parisiennes, 1863. New York: FIT Special Collections & College Archives. Source: Image taken by Author

Its Legacy

Without a doubt, the legacy of the simple white wedding dress continues today (Fig. 13). The use of the color white, ivory or cream in wedding dresses has stood the test of time, in fact, it is now considered quite adventurous when a bride gets married in another color.

While a bridal gown’s silhouettes vary today and dependent on the bride’s aesthetic, small waists and full skirts are still fashionable. Though the look is achieved with tulle petticoats rather than crinolines.

Necklines and accessories come in all different varieties today and, as always, the search for something unique and individual is at the forefront of every potential bride’s mind.

Fig. 13 - Peter Lagner. Wedding dress, Spring 2018. Satin, lace. Source: Pinterest

References:

- Ashelford, Jane, and Andreas Einsiedel. The Art of Dress: Clothes and Society, 1500-1914. London: National Trust, 1996. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/759883168.

- “Auguste Toulmouche.” Rehs Galleries, Inc. Accessed April 9, 2018. http://rehs.com/Auguste_Toulmouche_Bio.html.

- “Chitchat upon New York and Philadelphia Fashions for December,” Godey’s Lady’s Magazine 73 (1866): 548. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015027389397;view=1up;seq=529.

- Johnston, Lucy, Marion Kite, and Helen Persson. Nineteenth-Century Fashion in Detail. London: V&A Publications, 2005. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/741415660.

- Olian, JoAnne, ed. Wedding Fashions, 1862-1912: 380 Costume Designs from “La Mode Illustrée.” New York: Dover Publications, 1994. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/963446499.

- “The Hesitant Betrothed.” Sotheby’s. Accessed April 9, 2018. http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/lot.108.html/2005/19th-century-european-art-n08121.

- “Wedding Ensemble | American | The Met.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed April 9, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/107837.