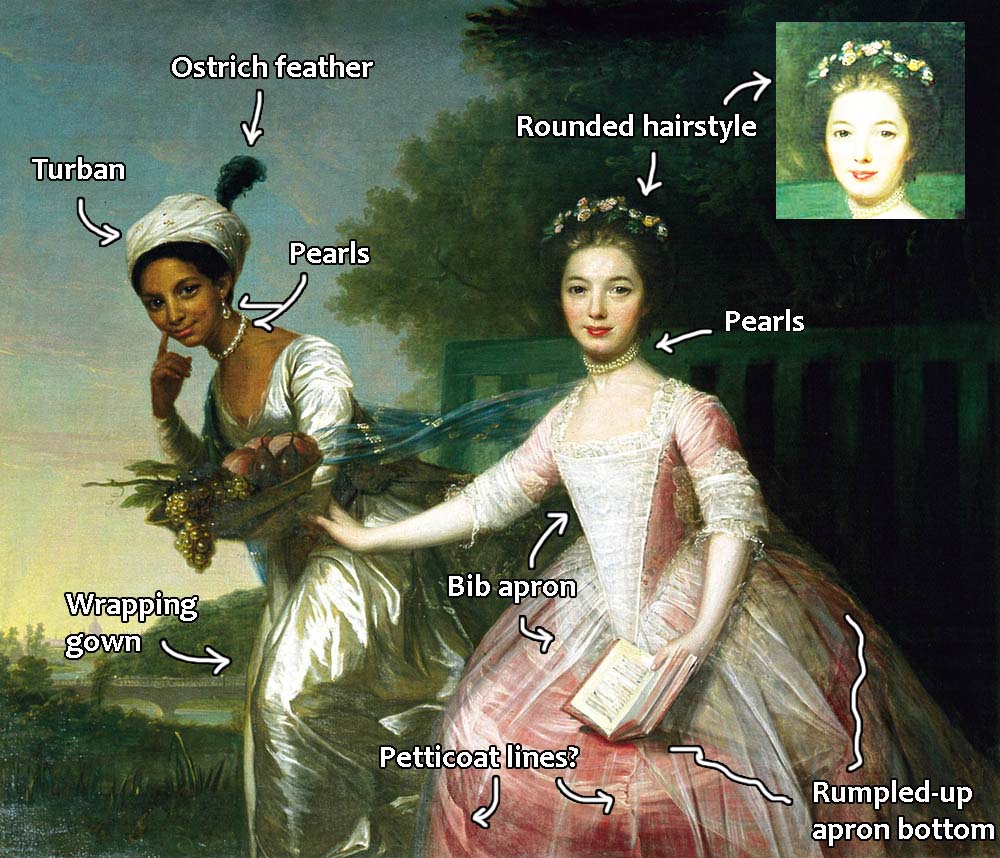

This 18th-century grand manner portrait of two cousins juxtaposes fashionable turquerie with luxurious but conventional children’s clothing.

About the Portrait

T

his portrait of two young women has been variously attributed to German artist Johan Zoffany and British artist Joshua Reynolds; in 2018 it was freshly attributed to Scottish artist David Martin (1737-1798) based on style, sitter gesture, and fabric treatment (Scone Palace). It is in the grand manner style of portraiture, with an awe-inspiring background and a lifelike treatment of the sitters and their clothing. It was painted on the grounds of the Kenwood estate in Hampstead, with a bit of London on the horizon at bottom left, and is currently dated to c. 1778 (Scone Palace). For reasons discussed in the next section (“About the Fashion: Lady Elizabeth Murray”), it more likely dates to a decade earlier.

Martin (Fig. 1) studied in Rome and London under painter Allan Ramsay and gained fame by painting the likes of American politician Benjamin Franklin and Scottish philosopher David Hume (Philip Mould). He worked with Ramsay until the latter died in 1784, at which point Martin moved to Edinburgh and made his name as the premier Scottish portraitist for the next ten years (Grove). While his portraits, especially early ones, are similar in style to Ramsay’s work, his large compositions like this one derive from the work of Joshua Reynolds (hence the early attribution) (Grove). His specialty lay in three-quarter-length portraits (Fig. 2).

Martin was commissioned to paint other members of the family, including Lady Margery Murray in the 1760s and William Murray, Lord Mansfield of Kenwood in the 1770s (Fig. 3).

About the Sitters

The sitter in the pink dress to the right is Lady Elizabeth Murray. Elizabeth was born in Poland in 1760 to Earl David Murray and his first wife Henrietta Frederica von Bünau. She was sent to live in England with her uncle in 1766 after her mother died. If this was indeed painted in 1778, Elizabeth would have been around eighteen years old; if our analysis of her fashion is accurate, she is actually less than ten. The average age of marriage at this time was in one’s mid-twenties, and indeed, Lady Murray married politician George Finch-Hatton in 1785 when she was twenty-five years old (Olsen 31).

The sitter in the white gown to the left is Dido Elizabeth Belle. She was born in England in 1761 to an African woman, Maria Bell(e), who had previously been enslaved in the Caribbean (Roulston 648). Dido’s father was British officer John Lindsay, who gave her into the care of his uncle William Murray at some point before her sixth birthday (English Heritage). Given that she was born out of wedlock, she probably had to battle the twin obstacles of her illegitimacy and British prejudice against her skin color for her entire life. Slavery was not officially legal in England, but not only were Black people still bought and sold within its bounds, the country was neck-deep in the transatlantic slave trade (English Heritage, Waterfield 129). Dido surely dealt with a great deal of prejudice throughout her life despite her sheltered position in the nobility. She eventually married after Murray’s death in 1793 to steward John Davinier and afterwards lived in London (English Heritage). She was one year younger than Elizabeth.

Elizabeth and Dido were second cousins and lived together with their great-uncle Lord Mansfield. They are quoted in period sources as enjoying each other’s company; it is clear that Dido was loved and accepted within his household (English Heritage). Lord Mansfield was a staunch abolitionist, and stated clearly in his will that Dido was a free woman; he also left an annuity of £100 to support her, much larger than her previous yearly allowance of £20 (English Heritage, Butchart 18:21).

It has been claimed that this painting presents Dido and Elizabeth “more or less as social equals,” with both looking straight at the viewer (Butchart 6:10). But this is not an unheard-of convention in British portraiture featuring Black servants (Fig. 4). Paintings of white European women being attended to by Black people, often in fantastical dress, were common fare in the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries (Waterfield 140). They almost always have the Black sitter fading into the background, off to the side, or looking at the white sitter to symbolize their loyalty (Fig. 5) (Waterfield 141, 144).

Another commonly seen gesture is for the white person to be touching the Black person fondly in some way, and for the Black person to be holding or offering flowers or fruit (Waterfield 144). These very gestures are being undertaken by Dido and Elizabeth. Compare their portrait to figures 5 and 6: the primary differences are that Dido is staring at the viewer and wearing clothing that, in another painting, Elizabeth herself may have been happy to don (discussed in the next section).

Their poses and expressions have been read as speaking of “sisterhood [and] companionship,” with Dido and Elizabeth on equal ground (Butchart 7:10), but many aspects of this painting actually are in the tradition of servant-and-master portraiture. Indeed, in the nineteenth century viewers saw only a mistress and her servant, and labeled the painting thusly. We now know that Dido was a gentlewoman in her own right and accord her more agency in the creation of this painting (English Heritage), but perhaps that was their goal all along: to create a work depicting equal status, while allowing viewers outside of the family to frame the relationship in a societally-acceptable way.

Fig. 1 - David Martin (Scottish, 1737-1798). Self-portrait, ca. 1760. Oil on canvas; 49.5 x 39.4 cm. Edinburgh: National Galleries Scotland, NG 569. Source: NGS

Fig. 2 - David Martin (Scottish, 1737-1797). Bust length portrait of a lady in a green and gold, 1785. Oil on canvas; 75 x 63 cm (29 1/2 x 25 in). London: Bonhams, Lot 8, April 12, 2007. Source: Invaluable

Fig. 3 - David Martin (Scottish, 1737-1798). Portrait of William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield (1705 – 1793), ca. 1770. Oil on canvas; 127 x 101.6 cm (50 x 40 in). Philip Mould Ltd. Source: HPIL

Fig. 4 - Stephen Slaughter (British, 1697-1765). Young Woman with Servant, 1740s. Oil on canvas; 122.6 x 99.7 cm (48 1/4 x 39 1/4 in). Hartford: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, 1987.1. The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund. Source: WAMA

Fig. 5 - Nicolas Lancret (French, 1690–1743). The Escaped Bird, ca. 1733. Oil on canvas; 46.0 x 54.6 cm (18 1/8 x 21 1/2 in). Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 40.478. Source: MFA

Fig. 6 - Joshua Reynolds (British, 1723-1792). Elisabeth, Sarah & Edward, children of Edward Holden Cruttenden, ca. 1763. Oil on canvas; 179 x 168 cm. Art Museum of São Paulo, MASP.00196. Donation to the National Life Insurance Company, 1952. Source: MASP

David Martin (Scottish, 1737–1797). Portrait of Dido Elizabeth Belle Lindsay (1761-1804) and her cousin Lady Elizabeth Murray (1760-1825), c. 1778. Oil on canvas. Perthshire: Scone Palace. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

About the Fashion

While caricatures are generally not accurate depictions of women’s dress, they can be useful in pointing out certain aspects that stood out to the artist. In 1777, tall hair and ruffles were all the rage (Fig. 7). But if British fashionable dress around this time looked anything like what is depicted in that print – assuming the hairstyles, while large, were not quite that high – then are Dido and Elizabeth in fashion at all?

Dido Elizabeth Belle

Dido is clothed in a long-sleeved V-neck white silk satin gown and a white turban with a dark ostrich feather – perhaps the turban is matching satin; it may also be fashionable Indian muslin (Butchart 4:40). There is a hint of a sheer tucker along her neckline, and she accessorized with a simple string of pearls and matching earrings.

By looking at portraits of ordinary women’s dress – even in the aristocracy – we know that what she is wearing is not what she would have worn day-to-day. There is also a 1779 source that records her wearing a cap in company, not a turban (Adams 3). This is an Orientalist fantasy costume, possibly made up by the artist, and to modern eyes serves to highlight her difference in skin color to Elizabeth. However, while this costume is not conventional dress, it is an artistic convention: having one’s portrait painted in this kind of white wrap dress in a scenic background was exactly the fashion in 1770s England, as well as in the decades before and after (Fig. 8).

This garment appears to be a kind of bedgown or wrapper, a feminine equivalent to a man’s banyan that was worn by women in the intimacy of their homes. Banyans and wrappers like this, which could be worn with or without stays, were inspired by an amalgamation of Asian dress, including Japanese kimono and Indian jama (Doering 29-31). They were used in portraiture in order to add elements of fantasy and exoticism, similar to the styles of robes à la turque, and dresses almost identical to Dido’s do in fact appear in turquerie portraiture (Sholtz 47-48). The connection becomes more obvious when we see a gown like Dido’s styled with low-waisted belts and fur-trimmed coats in addition to the turban and/or feather (Fig. 9): Dido is wearing ‘Turkish dress’.

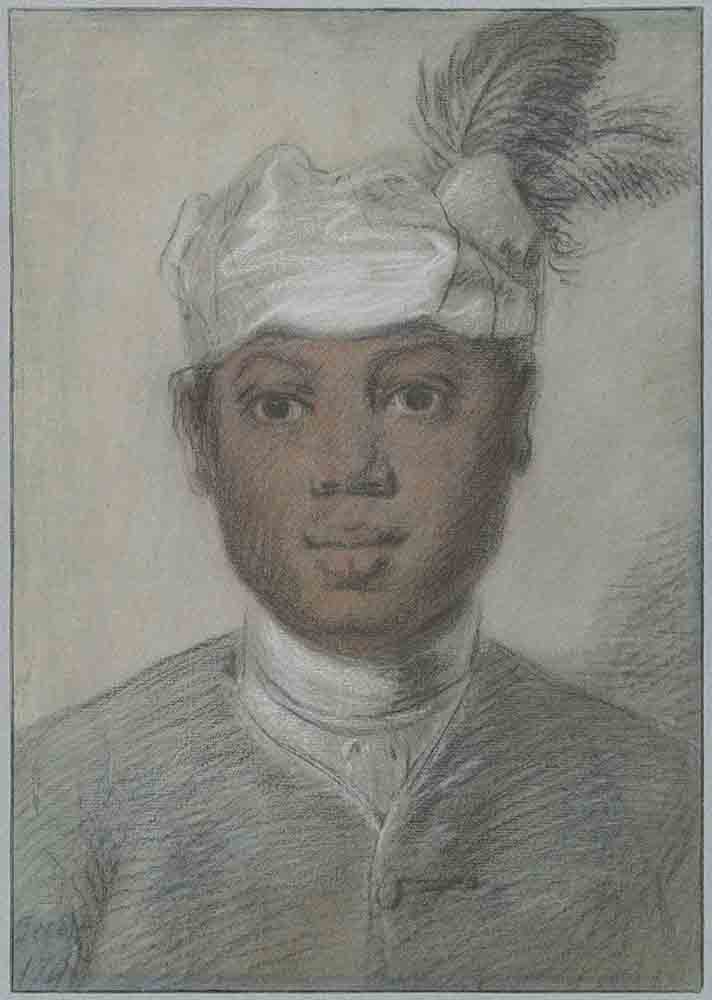

Fashionable turbans at this time derived from Turkish and Indian men’s clothing, but became divorced from their true context and culture of origin. In addition, Europeans often conflated peoples from completely different countries, so it came to be that any person of color in Europe who came near a white person with money and leisure time might find themselves suddenly be-turbaned (like Omai, the Polynesian man in figure 10). The kind of white turban we see on Dido especially is associated with this trend, specifically as part of servant uniforms for young Black boys (Fig. 11).

The viewer might find themselves thinking that Dido does not wear the fashionable hairstyle seen on Viscountess Crosbie because of this turban, but no – turbans could easily be worn atop these 1770s styles (Fig. 12). Her smaller hairstyle could be another marker of difference – but given that Elizabeth also has her hair styled low, perhaps not. This is the one clue in Dido’s outfit that this was not painted in the 1770s.

It was a fashion statement on the part of white women to don turbans like this, as seen in the previous figure, but we cannot divorce our interpretation of Dido’s clothing from her Blackness, as Martin’s or Murray’s relationship with her skin color may have influenced the clothing choices in the painting.

In her video “Researching David Martin’s Portrait of Dido Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray,” (2019) Nic Loven describes looking through Martin’s paintings and discovering that Dido’s turban cloth was an idiosyncrasy of Martin’s:

“Most interestingly, we observed a textile, or at least surface decoration, that occurs in five portraits. It is a repeating pattern of alternating gold beads and gold-beaded flowers. It appears on three wrapping gowns, on a silk textile wrapped around an infant, and on Dido’s turban. Suddenly, Dido’s dress seems much more of a reflection of the artists’ preference, skills, and imagination than anything to do with the color of Dido’s skin. Dido appears like any other fashionable young woman painted by David Martin.” (2:46)

(One of these portraits can be seen in figure 2.) This interpretation is perhaps too optimistic; Martin could have easily depicted her without a turban, or with one in a different color.

While turbans do appear in portraits like this, wrap gowns are more common. Many of the potential details of Dido’s dress are obscured by what she carries, so we can compare her image to others in similar dress to learn more. The long, tight sleeves are replicated on Lady Elizabeth Stanley in figure 13 and her blue-and-gold scarf is similar to the sash Alice De Lancey wears in figure 14. This garment – if it ever actually existed – was made in a simple T-shape (Doering 31).

Given the (fashionable) informality of her gown, we cannot guess whether she is wearing stays or not, but she would certainly have worn basic linens underneath to keep the gown clean. Dido has finished her outfit with a strand of pearls and pearl earrings, and has fashionable rouged lips and cheeks just like Elizabeth’s. It is difficult to say whether she was actually wearing makeup during sittings; the cousins’ red lips and healthy flushes could simply have been idealized by Martin, as was common practice for painters (Martin 27-28).

What stands out most about Dido’s portrayal in this portrait is not her gown, her turban, or even her unusually vivacious air, which is comparable to Viscountess Crosbie’s in figure 8: It is the fact that she and her cousin are not dressed in the same style. See Reynolds’ mother-daughter portrait in figure 15; both are depicted the same fashions

Fig. 7 - Carington Bowles (British, 1724-1793). A Morning Visit -or the Fashionable Dresses for the Year 1777, 1778. Mezzotint, paper; 35.4 x 25.1 cm. London: British Museum, J,5.108. Source: BM

Fig. 8 - Joshua Reynolds (British, 1723-1792). Diana (Sackville), Viscountess Crosbie, 1777. Oil on canvas; 240.7 x 147.3 cm (94 3/4 x 58 in). San Marino: The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, 23.13. Source: The Huntington

Fig. 9 - Jean-Baptiste Le Prince (French, 1734-1781). Lady in Turkish dress, ca. 1775. Source: Reinette

Fig. 10 - Joshua Reynolds (British, 1723-1792). Portrait of Omai, 1776. Oil on canvas; 236 x 145.5 cm (92.9 x 57.2 in). Collection of John Magnier. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 11 - Cornelis Troost (Dutch, 1696-1750). Head of a black young man with feathered turban, 1747. Paper; 37.3 × 26.3 cm. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, RP-T-1966-16. Source: Rijksmuseum

Fig. 12 - Hugh Douglas Hamilton (Irish, 1739–1808). A lady wearing a pink turban, Late 1770s. Pastel on laid paper; 22.5 × 18.2 cm (8 ⅞ × 7 ⅛ in). Private collection. Source: Lowell Libson & Jonny Yarker Ltd

It has been theorized that the two young women were allowed to choose their own clothing for this portrait (Loven 1:50). However, it is entirely possible that Martin or someone else decided that Dido should be dressed in this way. In large, complicated portraits of this kind, every detail is important and symbolic, and it is likely that neither girl had full agency over her wardrobe for this painting. If this was truly painted in the 1770s, then Elizabeth’s childish bibbed apron, for example, is not something that an eighteen-year-old would have chosen to be immortalized wearing.

Fig. 13 - George Romney (British, 1734–1802). Lady Elizabeth Stanley (1753–1797), Countess of Derby, 1776-78. Oil on canvas; 127 x 101.6 cm (50 x 40 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 49.7.57. Source: MMA

Fig. 14 - Thomas Gainsborough (British, 1727–1788). Mrs. Ralph Izard (Alice De Lancey, 1746/47–1832), 1772. Oil on canvas; 76.8 x 63.8 cm (30 1/4 x 25 1/8 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 66.88.1. Source: MMA

Fig. 15 - Joshua Reynolds (British, 1723-1792). Portrait of Hester Thrale and her daughter Hester, ca. 1777. Oil; 148.6 × 140.3 cm (58.5 × 55.2 in). Fredericton, New Brunswick: Beaverbrook Art Gallery. Source: Wikimedia Commons

While much has been made of their “presentation more or less as social equals” (Butchart 6:10) and Martin’s predilection for this kind of costume (Loven 3:00), these sitters are not truly being presented in the same way. Dido is standing, not seated, and her dress does emphasize her difference because it is different: it has a direct comparison in the same frame from a sitter who is not only in conventional dress but has the more common skin color (Bindman and West 29). However much Dido was loved and felt part of the family, this image represents what she surely could never fully escape from: standing out from the rest of her white English family (English Heritage). Perhaps this dress was her idea, and her way of embracing her difference – we may never know for sure.

Lady Elizabeth Murray

As noted above, the 1770s were notable for the sheer height of fashionable hairstyles, as well as frothy trimmings and several new styles of dress like the polonaise and caraco (Tortora 241). Pleated or ruched self-fabric or transparent organza trim was popular, and gowns were often made with jacket-length bodices and so that they appeared to have a second layer cutting away from the center front (Fig. 16). Fitted-back round gowns were commonly worn, but most women tended to have portraits painted wearing more complex fashions.

Elizabeth, who appears to be in her late teens in this painting, is wearing a pink satin ensemble that on second glance proves rather unusual. An eighteen-year-old in a late 1770s portrait should be dressed similarly to the women in figures 16 and 17, so why does she look so different? What first appears to be a white stomacher on her front is actually the bib of an apron, and because it covers the center front of her bodice we cannot tell what the dress actually looks like. It is doubtful that she is wearing a robe à la française with loose back pleats, as that had mostly gone out of popular fashion by this point (Leventon 167). But she is definitely not wearing any of the new cut-away styles; we would see lines and trim on the side of her bodice (Fig. 17). There are lines on the front of her skirt that seem to indicate a separate petticoat, but it is difficult to interpret them, partially because the entire dress is covered in an additional layer of transparent silk.

Overlining the entire gown in a transparent fabric may have been an artistic decision and not something that was present on the real dress. It is an unusual feature, especially odd because the main part of Elizabeth’s apron seems to be folded to the side underneath it, and she would not have worn an apron under a layer of dress. Her apron, as sheer and white as it is, is already a mark of luxury and taste; why would she obscure it? However, a few other examples of this style exist – notably, all on children’s dress – so perhaps it may have been a British fad in the 1760s and ’70s (Fig. 18).

Elizabeth’s bibbed apron (or pinafore) is important to our understanding of this painting. These were aprons “with a bib extension above the waist” (Cumming 21); the upper portion was pinned on to the gown with straight pins and the lower had ties for the waist. While adult women donned them in other countries, in England bibbed aprons in formal portraiture were an “iconographical [marker] of childhood” (Fig. 19) (Müller 98-99). While aprons were usually both protective and decorative, the aprons in these images are clearly only for decorative use, given their delicacy (Cumming 7). Its presence on Elizabeth tells the viewer that she has not yet entered puberty – strange, in a painting dated to her eighteenth year – and gives us a lead to find dress comparisons (Adams 3).

The young woman in figure 20 is sixteen, even younger than Elizabeth was in 1778, and is already wearing a simple fitted-back gown without an apron. The two girls in figure 21 are approximately eleven and twelve, and their gowns, complete with childish bib aprons, look similar to Elizabeth’s. Perhaps Lord Mansfield was loath to see her grow up? These children are wearing fashionable hairstyles despite their youth, though – where is Elizabeth’s? We find a closer comparison in figure 22, a detail from figure 6 above, which features a British girl of about twelve years of age. She wears the same kind of pink dress, bibbed apron, and short hairstyle festooned with small flowers, but her portrait was painted in the early 1760s.

Elizabeth’s hairstyle is oddly tame for an era in which fashionable hair “expanded to extreme sizes” (Tortora 241). In the Survey of Historic Costume (2003), Phyllis Tortora and Keith Eubank describe hairstyles in the latter half of the eighteenth century:

“In the 1760s: Dressed higher, frizzed around the face, later arranged in sausage curls flat against the head, running from ear to ear.

In the 1770s: Maximum size was reached – a towering structure supplemented by feathers, jewels, ribbons, and seemingly almost anything a lady could perch on top of her head.” (242)

Note the high, piled-up hairstyles of Viscountess Crosbie and Lady Elizabeth Stanley; Elizabeth Murray’s small, flowered hairstyle looks rather out of place. The enormous hairstyles came from France, and while some women ignored them, those that did tended to be either older, less fashionable, or living in places like the colonies that did not keep up with the French mode (Callahan 136). Even children in this era followed such fashions (Fig. 21); “Once a child reached the age of being dressed in clothing that reflected adult styles, hairstyles usually followed adult fashions” (Staples 388). Only very young children wore their hair low and unstyled (Fig. 19). While some rare paintings do feature older children with caps and cropped haircuts, Elizabeth’s hair is styled – just not in the 1778 fashion. Instead, it is in the rounded style popular in Britain from approximately 1763-68, seen on the sitter in figure 23. Hair is the easiest aspect of dress that one can alter in order to keep up with fashion, and thus the most important detail of this painting for dating it.

Another confirmation of her youth appears on her sleeves: compare Elizabeth to Countess Howe in figure 24. The Countess wears fashionable dress for the mid-1760s, including three-tier engageantes, or sleeve ruffles, and the upper arm is plain. No fashionable adult woman in this decade would be caught without elaborate lace or embroidery-covered engageantes (Fig. 23). Children’s gowns, however, had pleating or ruching decorating the upper arms from the 1730s onwards, and while they sometimes had engageantes, Elizabeth’s short, unruffled sleeves are a clear sign of childhood. While adult gowns in the 1770s began to leave off engageantes and take on these previously childish sleeve decorations (Figs. 16 & 17), Elizabeth’s hair is years out of fashion for the 1770s. Given her bib apron, it makes far more sense for her sleeves to be in the context of a long history of children’s gowns instead of a very recent fad for adult wear.

The only jewelry Elizabeth wears is a single strand of pearls looped around her neck twice (Loven 4:40). Children did wear jewelry for portraits like this (Fig. 21), so neither her necklace nor Dido’s pearl jewelry is out of place. Underneath her gown, Elizabeth must be wearing a linen shift, stockings, shoes, and a pair of light, boned stays to improve her posture (Olsen 95). She is probably also wearing several petticoats and some sort of hoop to hold out her dress in the fashionable shape (Olsen 96).

Was the girls’ caretaker ignorant of the previous decade of fashion, or does this portrait actually date much earlier than c. 1778? If this image is of Elizabeth Murray (born 1760) and Dido Belle (born 1761), the bibbed apron tells us that it cannot have been painted after 1772/3, as only after the age of twelve or so did girls assume adult clothing and leave them behind (Tortora 247). Yet that dating would not explain Elizabeth’s earlier styles; her hair, an easily changed aspect of dress, is in the fashion of the mid-to-late 1760s. Dido’s clothing does not help to answer the question of dating; while her Turkish-style ensemble was indeed fashionable in 1778, extremely similar outfits were worn in portraiture from the 1720s to the 1780s. It does, however, have to have been painted after 1765, as Elizabeth only came to live with her uncle the next year.

It simply does not make sense for an eighteen-year-old woman to be wearing a child’s bib apron and a hairstyle ten to fifteen years out of date. The conclusion we arrive at is that this was painted in the late 1760s and Dido and Elizabeth appear to our modern eyes much older than they actually were at the time of this painting – not unusual for art in this era (Beales 379). They were probably around seven to ten years old in this portrait, which may explain the childish delight of Dido’s pose.

If this painting is truly from the late 1770s, then they were purposefully styled to seem dated and extremely childlike – for what reason, we cannot guess. But given that no hard evidence for the c. 1778 dating has been publicized, we feel comfortable re-dating this portrait and revealing that the sitters are not young women but lovingly styled older children.

Fig. 16 - George Romney (British, 1734-1802). Portrait of a Young Woman in Powder Blue, ca. 1777. Oil on canvas; 73.7 x 62.2 cm (29 x 24 ½ in). Private Collection. Source: Fergus Hall Master Paintings

Fig. 17 - Laurent Pécheux (Italian, 1729-1821). Portrait of the Marquise Margherita Sparapani Gentili Boccapaduli (1735-1820), 1777. Museo di Roma. Source: MdR

Fig. 18 - Thomas Beach (British, 1738–1806)). Maria Craven (1769–1851), Later Countess of Sefton, as a Young Girl, 1776. Oil on canvas; 75.5 x 63 cm. Liverpool: Walker Art Gallery, WAG 10502. purchased 1984. Source: ArtUK

Fig. 19 - George Romney (British, 1734–1802). Portrait of a Girl (said to be Miss Collingwood), 1767. Oil on canvas; 50.8 x 43.2 cm. Liverpool: Walker Art Gallery, WAG 2415. Source: ArtUK

Fig. 20 - Jean-Étienne Liotard (Swiss, 1702-1789). Portrait de Marie-Thérèse Liotard (1763-1793), fille de l'artiste, vue de profil à gauche, 1779. Graphite pencil, black and red chalk; 24.2 x 18.9 cm. Musée d'art et d'histoire, Ville de Genève, 1934-0031. Source: MAH

Fig. 21 - Artist unknown (Polish). Charlotte and Ferdinande von Hochberg, sisters of Hans Heinrich VI, ca. 1775. Pszczynie: Muzeum Zamkowym. Source: Spotkania z Zabytkami

Fig. 22 - Joshua Reynolds (British, 1723-1792). (Detail) Elisabeth Cruttenden, b. 1752, ca. 1763. Oil on canvas; 179 x 168 cm. Art Museum of São Paulo, MASP.00196. Source: MASP

Fig. 23 - George Romney (British, 1734-1802). Portrait of Elizabeth Leigh, ca. 1765. Oil on canvas; 76.8 x 63.5 cm (30 1/4 x 25 in). San Marino, CA: The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens., 2008.7. Source: Huntington

Fig. 24 - Thomas Gainsborough (British, 1727-1788). Mary, Countess Howe, ca. 1764. Oil on canvas; 243.2 x 154.3 cm. London: Kenwood (English Heritage), 88028783. Iveagh Bequest, 1929. Source: ArtUK

Its Legacy

This portrait was not associated with Dido Belle until the mid-20th century, when research was done in the family archives. It was labeled “Lady Elizabeth Finch-Hatton with a Negress Attendant” sometime before 1904, and its frame label even in 2018 neglected to mention its Black sitter (Weaver). But Amma Asante, Misan Sagay and Damian Jones saw Dido’s potential and made a movie about her story: Belle (2013) (Fig. 25). With its release, the portrait saw a sharp increase in visitation and interest, and Dido’s story has been heavily publicized.

Fig. 25 - Anushia Nieradzik (Polish, active 1978-present). Gugu Mbatha-Raw as Dido Elizabeth Belle and Sarah Gadon as Lady Elizabeth Murray in “Belle", 2014. Source: The Edmonton Journal

Historical costumers have latched on to Dido’s ensemble and recreated it at least twice, producing research and videos around their versions. In 2018, the BBC4 show A Stitch in Time followed fashion historian Amber Butchart as period tailor Ninya Mikhaila and her team worked to recreate the gown and turban in her size (as they do for every historical costume recreation in the series) (Fig. 26). In 2019, the team at Crow’s Eye Productions also recreated the gown, this time hiring an additional actress to portray the white sitter in an imitation of the actual portrait (Fig. 27). Interestingly, they decided not to recreate the pink ensemble, claiming difficulty and expense (partially due to its transparent overlay).

Both teams appear to have used silk satin and referenced 18th-century bedgown patterns for Dido’s outfit.

References:

- Adams, Gene. “Dido Elizabeth Belle: A Black Girl at Kenwood.” Camden History Review 12, no. 1-84 (1984): 10-14. https://sharonlathanauthor.com/wp-content/uploads/Dido-Elizabeth-Belle_-a-black-girl-at-Kenwood.pdf

- Beales, Ross Jr. “In Search of the Historical Child: Miniature Adulthood and Youth in Colonial New England.” American Quarterly 27, no. 4 (1975): 379-98. JSTOR (subscription required)

- Bindman, David, and Helen West. “Court and City: Fantasies of Domination.” in Bindman, David, Henry Louis Gates, and Karen C. C. Dalton. The Image of the Black in Western Art. Vol. III. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/862149890

- Butchart, Amber, Ninya Mikhaila, Harriet Waterhouse, and Hannah Marples. “A Stitch in Time S01E04 Dido Belle.” Elizabeth. YouTube, 12 February 2018. Accessed 11 July 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GSDDJrlJukM

- “Dido Elizabeth Belle.” English Heritage. Accessed 11 July 2020. English Heritage

- Doering, Mary D. “Banyan Dressing Gown, 1600-1714.” In Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe. José Blanco, Mary D. Doering, Patricia Hunt-Hurst, and Heather Vaughan Lee, eds. Santa Barbara, California : ABC-CLIO, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/904505699

- Haykin, Michael A. G. “Belle: An 18th-Century Triumph Of Humanity”: A Review Of Belle: The Slave Daughter And The Lord Chief Justice By Paula Byrne.” The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 23 February 2015. Accessed 14 July 2020. AFC|SBTS

- Leventon, Melissa. What People Wore When: A Complete Illustrated History of Costume from Ancient Times to the Nineteenth Century for Every Level of Society. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2008. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/939099057

- Loven, Nic. “Researching David Martin’s Portrait of Dido Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray.” CrowsEyeProductions. YouTube, 15 October 2019. Accessed 11 July 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NXjhjU4JDdA

- Martin, Morag. Selling Beauty: Cosmetics, Commerce, and French Society, 1750-1830. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/276139297

- Müller, Anja. Framing Childhood in Eighteenth-Century English Periodicals and Prints, 1689-1789. Farnham: Ashgate, 2009. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/939766156

- Olsen, Kirstin. Daily Life in 18th-Century England. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1999. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/39913527

- Philip Mould Ltd. “Portrait of William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield (1705 – 1793), c.1770.” Historical Portraits Image Library. Accessed 12 July 2020. HPIL

- Rodgers, David. “Martin, David.” Grove Art Online.

2003; Accessed 12 Jul. 2020. OAO (subscription required) - Roulston, Chris. “Framing Sensibility: The Female Couple in Art and Narrative.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900 46, no. 3 (2006): 641-55. Accessed July 13, 2020. JSTOR (subscription required)

- “Scone Palace and the famous portrait of Lady Elizabeth Murray and Dido Elizabeth Belle featured on Fake or Fortune.” Scone Palace, 28 August 2018. Accessed 12 July 2020. Scone Palace

- Sholtz, Mackenzie Anderson. “Caraco Jacket, 1715-1785.” In Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe. José Blanco, Mary D. Doering, Patricia Hunt-Hurst, and Heather Vaughan Lee, eds. Santa Barbara, California : ABC-CLIO, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/904505699

- Staples, Kathleen A., and Madelyn Shaw. Clothing Through American History: The British Colonial Era. Santa Barbara, Calif: Greenwood, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/882969600

- Waterfield, Giles. “Black Servants.” In Below Stairs: 400 Years of Servants’ Portraits. London: National Portrait Gallery Publ, 2003. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/834455426