Decorative and strengthening embroidery on stockings in Europe and America during the 16th-19th centuries.

The Details

Clocking has been used in hosiery since the 16th century. Historian Daniel Delis Hill writes about the etymology of the term in The History of World Costume and Fashion (2011):

“The ankles of men’s nether hose were also decorated with lavishly embroidered sections called clocks, from a Dutch word meaning bell-shaped.” (398)

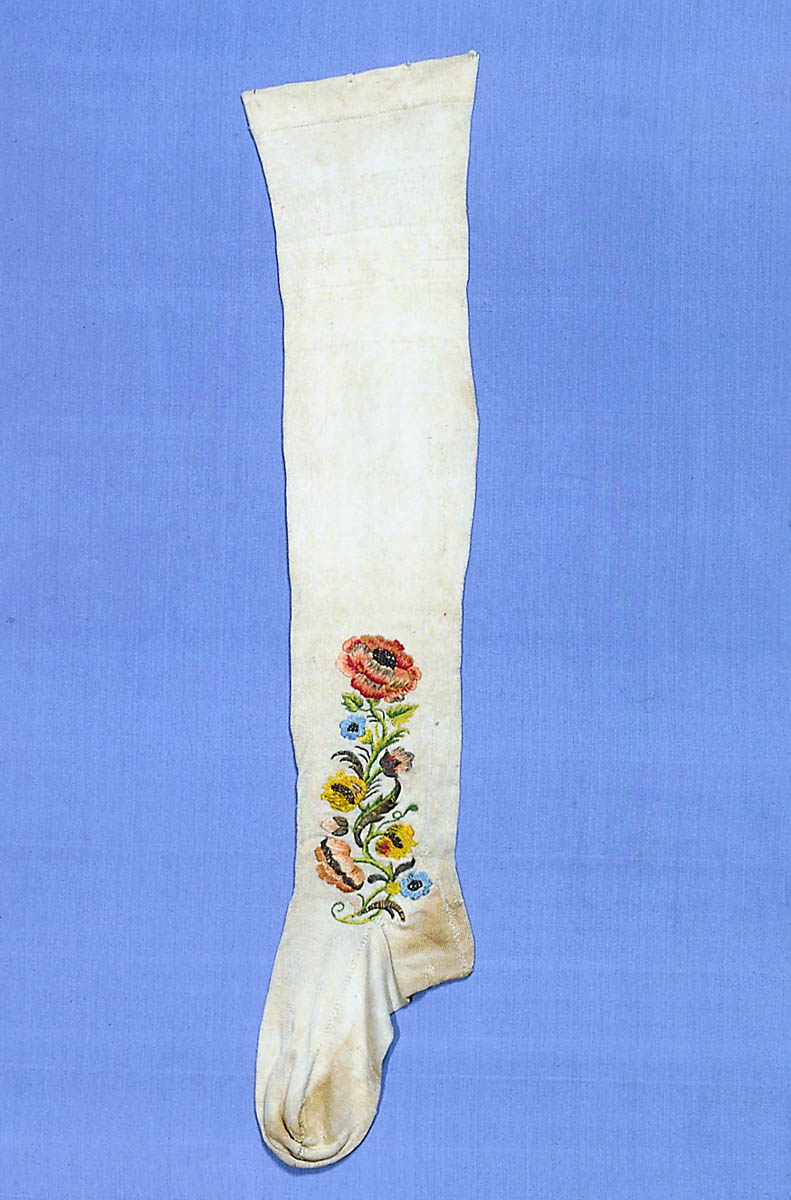

Clocks were a unisex feature: A pair of men’s clocked woolen boot-hose from the 17th century can be seen in figure 1, and a painting of a woman wearing clocked stockings in figure 2.

Jose F. Blanco writes in Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe (2015) that:

“In addition to buckles, decorative stockings worn by men and women enhanced the opulent, patterned textiles of their clothing. In the latter part of the 18th century, fashionable stockings made of silk or cotton were generally white. They were often adorned with knit or embroidered patterns in metallic thread at the ankle, referred to as ‘clocks’ or ‘clocking’. Of course, they existed along with more utilitarian stockings of linen and worsted wool.” (110)

Author Nan H. Mutnick writes for the Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion (2010):

“During the nineteenth century, hosiery was made from cotton, silk, or very fine wool. Those living in the colder climates, such as northern Canada, would have used heavier-weight wool for warmth. Stripes and embroidered patterns called clocks (small embroidered, woven, or knitted decorations on the back of the heel or side of the stocking) were used.” (135-136)

Clocks could contrast with the color of the rest of the stocking (Fig. 3), and were generally positioned to be seen over shoes. An expensively clocked silk stocking with silver embroidery (now tarnished to black) can be seen in figure 4; as is apparent from the staining, white stockings were harder to keep clean. Both men and women wore clocked hose and stockings until the early 19th century; while breeches were worn, men sported clocks (Fig. 5), but they became a woman’s decorative element after trousers were introduced in menswear. Phyllis Tortora mentions the late 19th century style in Survey of Historic Costume (2015):

“Usually stockings matched the color of the dress or shoes. Embroidered and striped patterns were popular. For evening in the 1870s, white silk stockings with colored clocks (a small design) were preferred, whereas black became popular in the 1880s.” (399)

A pair of late 19th-century white silk stockings with monochromatic blue embroidery can be seen in figure 6.

Jose F. Blanco also describes hosiery in the 1840s and beyond:

“Stockings were another essential accessory that women in the antebellum period rarely did not wear. Most women wore plain white, pale pink, or mauve stockings made of machine-knitted silk or cotton. Some stockings had a decorative design on one side known as clocking.” (27)

“An essential item of underwear worn during this period for men and women was stockings. These were knitted and made of silk, cotton or wool. Decorative embroidery known as clocking decorated the front of the stocking. By the 1840s, stockings were held up above the knee with elastic cords.” (256)

A pair of synthetic-purple machine-knitted girl’s socks can be seen in figure 7; the clocking on them is minimal, and mostly for strength and security, as with the white stitching at heel and toe. As Blanco notes, there is an elasticised section at the top.

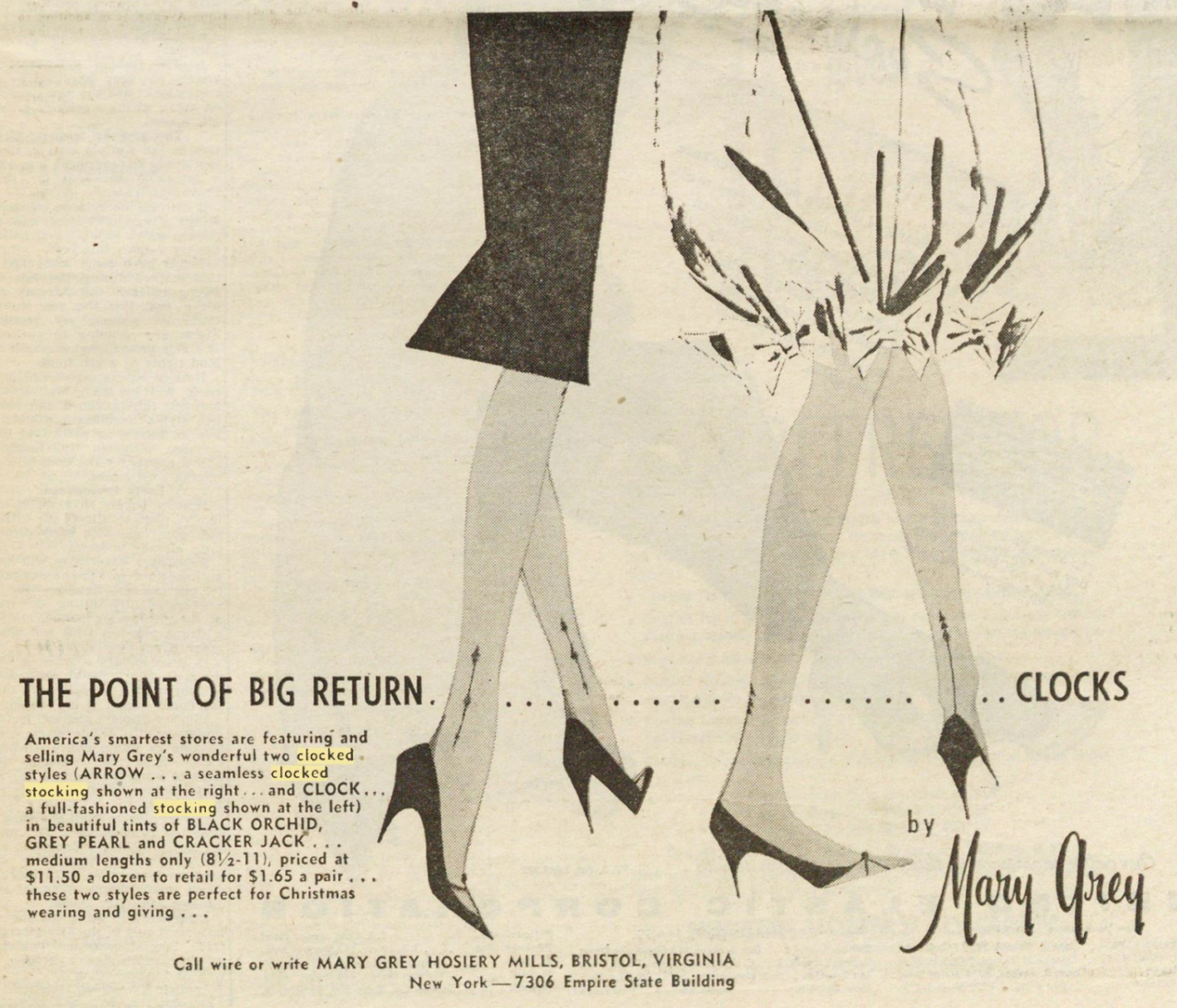

The term ‘clocking’ faded in use after the late 19th century, but certain hosiery designers continued to use it for their products. Mary Grey’s ads for “clocked stockings” in Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and Women’s Wear Daily continued through the 1950s (Fig. 8).

Fig. 1 - Designer unknown (English). Pair of hose, 1640s. Knitted wool; (length: 36.5" leg, 10.25" foot in). London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, T.63&A-1910. Source: VAM

Fig. 2 - William Hogarth (English, 1697-1764). Detail from The Tavern Scene (A Rake's Progress), between 1732 and 1735. Oil on canvas; full painting 62.5 x 75 cm (24.6 x 29.5 in). London: Sir John Sloane's Museum, 1868,0822.1530. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (England). Stocking worn in Westmoreland by Sir William Fleming, ca. 1750. Frame-knitted linen with silk design; (overall length 24 in, foot length 10 in). Colonial Williamsburg, 1967-131,1. Museum purchase. Source: CW

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (European). Pair of clocked stockings, 1750-1800. Silk; white knitted silk with polychrome silk and silver embroidered clocks; 21 x 56 cm (8 1/4 x 22 1/16 in). Boston: The Museum of Fine Arts, 43.1952a-b. The Elizabeth Day McCormick Collection. Source: MFA

Fig. 5 - Pierre Maleuvre (engraver) (French, 1740-1803). Pierson, Róle de Blaizot, dans la Pie Voleuse, Early 19th c.. Printing ink; paper; paint; wash; 22.5 x 15.5 cm. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, S.1033-2010. Harry R. Beard Collection, given by Isobel Beard. Source: VAM

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (French). Stockings, 19th century. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.54.7.4a, b. Gift of Mr. Edgar Tallman, 1954. Source: MMA

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown (American). Girl's socks, ca. 1860. Silk knit; 12.7 x 8.9 cm (5 x 3.5 in). Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1976-56-8a,b. Gift of Mrs. A. Douglas Oliver, 1976. Source: PMA

Fig. 8 - Mary Grey (American, active 1946-1972). The Point of Big Return...Clocks, 1958. Newspaper. Women's Wear Daily, Vol. 97, Iss. 97 (Nov 14, 1958): 19. Source: ProQuest

Its Afterlife

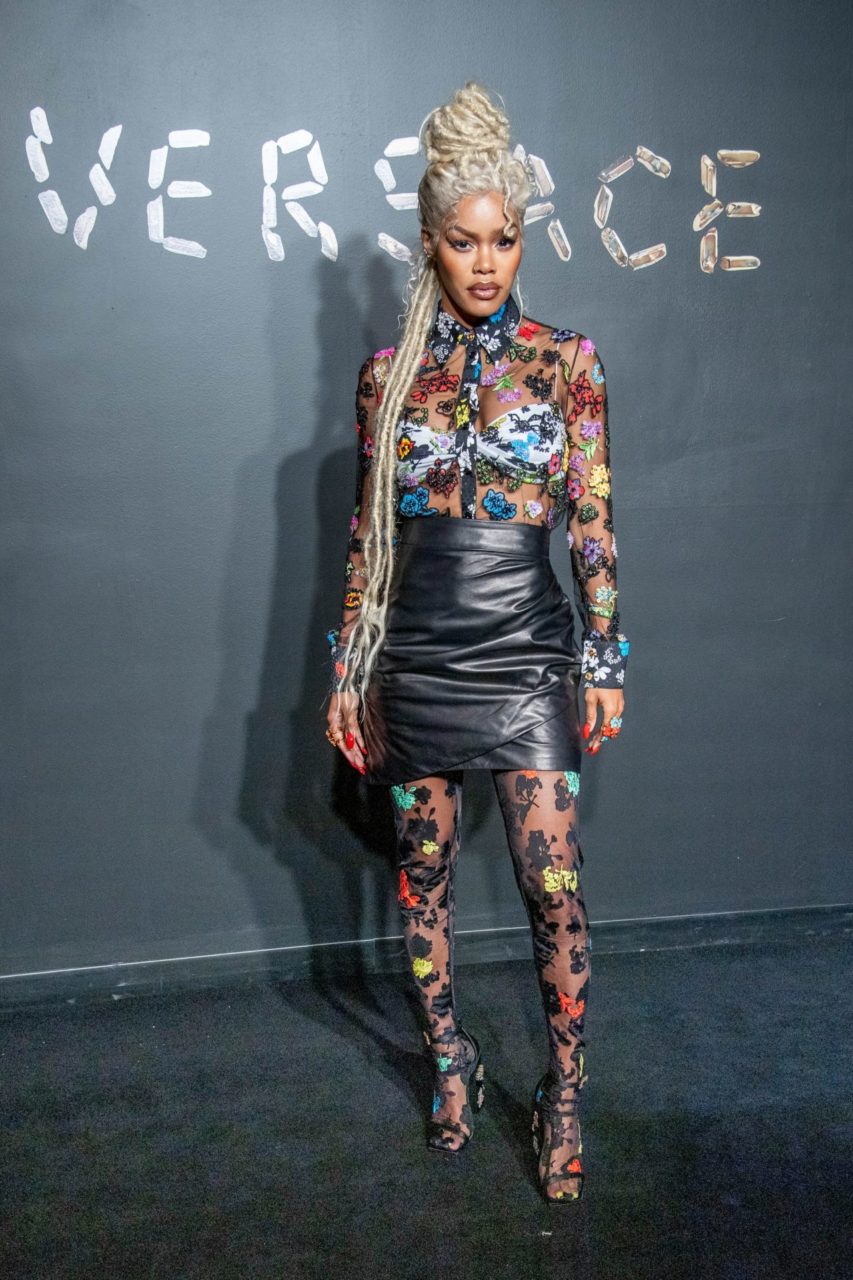

While the term ‘clocking’ is no longer used, its legacy is clear. Embroidered patterns on stockings experienced a resurgence in popularity in the 2010s. While they are rarely so sparse and asymmetrical as traditional clocking, unique designs abound (Fig. 9). Embellishment is popularly machine-made synthetic lace and appliqué work (Fig. 10), but rhinestoning is also popular, if harder to maintain day-to-day (Fig. 11). Such tights are often seen on the street, but usually in subtle or monochromatic patterning, as with the Rodarte and Stèphane Rolland examples here. The Dolce & Gabbana tights are suitable for the runway and red carpet, but the Versace tights in figure 12 might be seen on the very fashionable.

Fig. 9 - Dolce & Gabbana (Italian, active 1985-). Spring 2016 RTW, Spring 2016. Source: Vogue

Fig. 10 - Rodarte (American, active 2005-). Look 1, Fall 2010 RTW. Photo by Marcio Madeira, Model Antonella Graef. Source: Vogue

Fig. 11 - Stéphane Rolland (French, active 2007-). Tights at Stéphane Rolland Couture Fall 2010, Fall 2010. Imaxtree. Source: Livingly

Fig. 12 - Versace (Italian, active 1978-). Teyana Taylor Matched Her Sheer Embroidered Blouse With Her Tights, Spring 2019 Collection. Photo by Roy Rochlin. Source: Popsugar

References:

- Blanco, José F. Clothing and Fashion. American Fashion from Head to Toe. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/908333896

- Hill, Daniel Delis. History of World Costume and Fashion. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/939043732

- Mutnick, Nan H. “Hosiery.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: The United States and Canada, edited by Phyllis G. Tortora, 135–136. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Accessed October 03, 2018. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/BEWDF/EDch3020

- Tortora, Phyllis G. and Sara B. Marcketti. Survey of Historic Costume: Student Study Guide. 6th edition. New York ; London: Fairchild Books : Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Inc, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/910929404