OVERVIEW

Fashion of the 1850s for both men and women was in a colorful, exuberant style with luxurious fabrics and relaxed cuts. Technological innovation had a large impact on clothing in this period, from the invention of the cage crinoline to the increasing availability of the sewing machine.

Womenswear

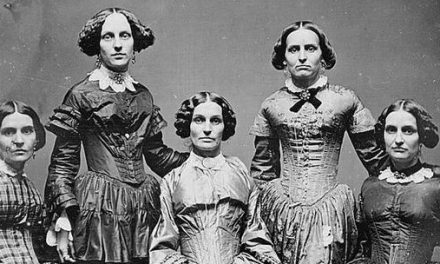

The fashionable silhouette of the 1850s was defined by a small waist, drooping shoulders, and a voluminous skirt that steadily grew in size through the decade. By far, the most important characteristic of 1850s womenswear was the dome-shaped skirt with its fullness evenly distributed (Severa 96). The large skirt was supported underneath by multiple petticoats, sometimes up to seven at once (Fig. 1). At least one of these petticoats would typically be a crinoline, a type of petticoat that was stiffened with horsehair. In 1856, the cage crinoline, a device consisting of a series of concentric steel hoops, was introduced; it provided immediate relief from the multiple heavy and cumbersome petticoats (Bruna 178-179). It allowed skirts to reach new proportions, especially between 1858 and 1862 (Thieme 41). Relatively inexpensive, the cage crinoline was worn at all levels of society (Foster 14). Fashion historian C. Willett Cunnington notes:

“The prevalence of the fashion can be gathered from the statement that in 1859 Sheffield was turning out enough crinoline wire a week for half a million crinolines.” (205)

During the first years of the 1850s, the style of the late 1840s was still seen, marked by the long torso stiffened with constricting corsets (Fig. 2). But by 1853, the long, dropped waistline of the 1840s rose to its natural position, and as a result, the emphasis on tight-lacing lessened as the corset shortened and flared (Fig. 3) (Cunnington 192; Severa 98). Daytime dresses featured high necklines, often completed with a wide white collar, long sleeves, and most frequently, a straight or curved waistline (Severa 175). A common bodice decoration was the V-shaped “bretelles” that spread from the center waist to the outer edges of the dropped shoulders, usually finished in trim (Fig. 4) (Thieme 37). The narrow fitted sleeve of the 1840s began to loosen at the end of the decade, and in the 1850s, sleeves became wide and open, expanding from either the shoulder or the elbow. These sweeping “pagoda” sleeves were worn with removable white undersleeves called engageantes that puffed and closed at the wrist (Fig. 5) (Tortora 363). Reaching the widest point from 1857 to 1860, the pagoda sleeve was often trimmed with bows and fringed epaulettes (Foster 83; Thieme 37). Indeed, passementerie trims such as fringe, tassels, ribbons, braids, and cords were very much in vogue during the 1850s for use on both the bodice and skirt (Fig. 6) (Johnston 178).

Fig. 1 - Designer unknown (American). Petticoat, 1855-1865. Cotton. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.768. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 2 - Photographer unknown (American). Unidentified African American Woman, ca. 1850. Daguerreotype with applied color; 7.0 x 5.5 cm. Rochester, NY: George Eastman Museum, 1969:0201:0020. Source: George Eastman Museum Flickr

Fig. 3 - Maull & Polyblank (British, Firm Active 1854-1865). Unknown Woman, ca. 1855. Albumen print; (7 7/8 x 5 3/4 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG P106(19). Purchase, 1978. Source: National Portrait Gallery

During the 1850s, it became common to have a dress made in two pieces: a skirt and a separate matching bodice. Sometimes a skirt would have two matching bodices, one for day and one for evening. A bodice that was especially fashionable was the basque waist, a jacket-like bodice that extended over the hips (Figs. 3-4, 6-7). The volume of the 1850s skirt was often emphasized by tiered flounces, sometimes made in fabric that was woven a disposition, meaning it was woven specifically for these flounces (Fig. 3, 6, 8) (Severa 96; Thieme 37). In fact, materials were a focal point in fashion, since the huge skirts displayed fabrics to such great effect. Silk was particularly fashionable as it was lightweight over the multiple petticoats but had enough body to hold its shape (Cunnington 171; Tortora 360-361). Patterned silks featuring flamboyant colors in stripes and plaids were the height of fashion (Fig. 5, 7) (Severa 95, 155). In the evening, the high-necked, long-sleeved day bodice was traded for one baring the chest and shoulders. Evening sleeves were short, and frequently, the waistline would end in a point (Fig. 8) (Tortora 365).

Fig. 4 - Aristides Oeconomos (Austrian, 1821-1887). Portrait of a Young Woman, Seated, Wearing a Pink dress, 1857. Oil on canvas; (35 13/16 x 27 9/16 in). Source: MutualArt

Fig. 5 - Thomas M. Easterly (American, 1809-1882). Unidentified African American woman with book, Late 1850s-Early 1860s. Daguerrotype. St. Louis: Missouri History Museum. Source: The Civil War in Missouri

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (American). Woman's dress with Day and Evening Bodices, ca. 1858. Silk taffeta and fringe. Philadelphia: The Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1948-74-1a--c. Bequest of Miss Mary Bragg Merrill, 1948. Source: The Philadelphia Museum of Art

Regarding outerwear, the shawl reigned supreme as it draped beautifully across the sweeping skirts. Cashmere shawls, either imported from India for those who could afford it, or the cheaper imitations made in France, England, and Scotland, were the dominant choice (Fig. 9) (Fukai 192; Severa 103). Mantles, a three-quarter length coat fitted in the front but left loose in the back, with long, open sleeves, was also a common option (Cunnington 175-181; Tortora 366). Other elements of dress were also influenced by the crinoline skirt. Before the introduction of the hoop skirt, pantalettes, a set of long, straight-legged drawers, were no longer worn when one reached womanhood. However, once the cage was widely worn, drawers became a staple of the female undergarments once again, as the swinging cage could expose the lower leg (Severa 99; Lynn 170). Additionally, fine heeled boots that laced well above the ankle came into fashion, as the crinoline exposed the feet as well (Laver 184).

The hairstyle in the 1850s was parted in the center, brushed down and arranged heavily on the sides, completely covering the ears (Severa 155). Bonnets, defined as a hat tied with strings under the chin, remained the vastly dominant choice of millinery, but they changed subtly from the inhibiting style of the previous decade. Brims shortened away from a woman’s face, and it was worn further back on the head, exposing more hair (Fig. 10) (Shrimpton 12). In the late 1850s, hair was increasingly worn quite heavy and low at the back. An alternative to the traditional cottage bonnet developed to accommodate this new hairstyle; the fanchon bonnet was a small triangular confection lacking any differentiation between crown and brim (Fig. 11). It also eliminated the bavolet, the panel of fabric attached to the back of a bonnet to conceal the neck (Ginsburg 83).

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown (European). Dress, ca. 1857. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.69.32.1a, b. Gift of Mrs. Edwin R. Metcalf, 1969. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 8 - Artist unknown (American). Graham's Magazine: Evening Dresses, June 1858. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Public Library, rbc4664. Source: Los Angeles Public Library

Fig. 9 - Alfred-Émile-Léopold Stevens (Belgian, 1823-1906). Departing for the Promenade (Will You Go Out with Me, Fido?), 1859. Oil on panel; (24 1/4 x 19 1/4 in). Philadelphia: The Philadelphia Museum of Art, W1893-1-106. The W. P. Wilstach Collection, bequest of Anna H. Wilstach, 1893. Source: The Philadelphia Museum of Art

Fig. 10 - James Collinson (British, 1825-1881). The Empty Purse (Replica of "For Sale"), 1857. Oil on canvas; 610 × 492 cm. London: Tate Museum, N03201. Presented anonymously 1917. Source: Tate Museum

Fig. 11 - Designer unknown (English). Bonnet (Fanchon), ca. 1858-1865. Linen net, lace, silk velvet ribbon, feathers, glass beads. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.2007.211.172. Purchased with funds provided by Suzanne A. Saperstein and Michael and Ellen Michelson. Source: Google Arts and Culture

Fig. 12 - Designer unknown (American). Dress, 1856-1858. Silk taffeta and fringe, machine-embroidered net, bobbin lace. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 50.474a-b. Gift of Mrs. Harriet Ropes Cabot and Edward Jackson Lowell Ropes. Source: Museum of Fine Arts

Fig. 13 - Artist unknown (American). Amelia Bloomer, October 1851. Source: Council Bluffs Public Library

Innovation in technology and chemistry had a large impact on fashion in the 1850s. The sewing machine, first patented in the 1840s, saw many important developments. In 1851, Issac Singer began manufacturing sewing machines, using the lock stitch technology invented by Elias Howe, and by the end of the decade, the Singer sewing machine was used in many households for home sewing (Tortora 352, 358; Brittanica). Patterns and diagrams for the home sewer were newly available in magazines such as Godey’s Lady Book (Severa 90-91). Even Parisian dressmakers were reportedly using the “American sewing machine” by 1858 (Cunnington 192). 1856 saw one of the most important fashion innovations of the nineteenth century; William Perkin, at only eighteen years old, invented the first synthetic aniline dye, a rich purple hue he called “mauveine” (Tortora 361). He made the discovery by accident when he was attempting to produce quinine to treat malaria, and only a year later, Perkin opened his own factory to mass produce his serendipitous new dyestuff (Metych). Mauve quickly became wildly fashionable (Fig. 12), leading to such popularity that the craze was nicknamed “Mauve Measles.” By 1859, chemists were devising new aniline colors such as fuchsine, a deep crimson (Garfield 65, 78). Historian Simon Garfield, in his book Mauve: How One Man Invented a Color that Changed the World, wrote:

“Within two years of Perkin’s invention it seemed that everyone was having a go at dyemaking. Industry had show Victorian chemists what was possible, and now nothing seemed beyond achievement; an eighteen-year-old had created a new shade for a woman’s shawl, and the full force of chemical ambition was unleashed.” (69)

Any discussion of 1850s womenswear would be incomplete without mention of Bloomers. In Seneca Falls, New York, in 1851, feminist leaders Elizabeth Smith Miller, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Amelia Jenks Bloomer shocked the nation when they stepped out in their reform costume: a shortened skirt worn over “Turkish trousers” (Fig. 13) (Fischer 79). The outfit, and more specifically the trousers, were nicknamed “Bloomers” after Amelia, despite the fact that she did not invent the costume (Tortora 359). An explicit reaction against the increasingly restrictive and burdensome women’s fashions, the Bloomer costume became inseparably associated with the early feminist movement, and it was an 1850s sensation. Reported, and more often savagely ridiculed, throughout the press, bloomers never became mainstream dress. The idea of women wearing trousers offended deeply held beliefs about men and women and their “separate spheres,” and stoked wild fears about a possible sexual revolution (Laver 181-182; Fischer 3, 83-85). While only about 100 notable women are known to have worn the bloomer costume, and even its first proponents eventually abandoned it, it made an indelible mark on the fashion landscape of the mid-nineteenth century, and adaptations survived in later athletic womenswear (Severa 88; Tortora 359).

Fashion icon: Empress Eugénie de montijo (1826-1920)

Empress Eugénie, a Spanish countess born Eugenia de Montijo, was the ultimate fashion leader of the 1850s and 1860s, reigning over the glittering Tuileries Palace in Paris as Empress of the French during the Second Empire until its fall in 1870 (Fig. 1). She was born on May 26, 1826 in Granada, Spain, and married Napoleon III on January 30, 1853 (Seward ch. 1-2). Empress Eugénie, considered a great beauty, was instrumental in returning the court of France to lavish opulence (Fig. 2), and Paris regained its status as a world capital (Tortora 355). The Second Empire as a whole seemed to recall the ancien régime, and Eugénie was particularly drawn to the memory of Marie Antoinette (Versailles). She cultivated a style inspired by the eighteenth century: rich pastel silks, an abundance of bows and ribbons, undulating floral patterns (Trubert-Tollu 35). Many 1850s developments in fashion became associated with Eugénie as well. The popularization of aniline dyes was encouraged by Eugénie’s enthusiasm for mauveine, as she believed it matched her violet eyes (Garfield 59-61). She became synonymous with luxurious crinoline era fashion, nicknamed by Parisians “La Reine Crinoline,” or Queen Crinoline (Seward ch. 3).

Interestingly, Eugénie initially seemed to have little interest for fashion, often preferring to wear a plain black faille dress (Tortora 355; Seward ch. 3). She could be reluctant to wear a new fashion, and wore rather simple dresses in private (Trubert-Tollu 35). However, Eugénie’s numerous official duties required a more luxurious approach to dress, and she soon amassed an impressive wardrobe for such occasions, which she recognized as prime moments to promote French fashion. Paris dressmakers Mmes Vignon and Palmyre and milliner Mme Virot are just a few of the French suppliers she patronized (Seward ch. 3). At the end of the decade, Eugénie helped to launch the career of Paris’ first couturier, Charles Frederick Worth. She was stunned by her friend Princess Pauline von Metternich’s new gown, which Eugénie called a “marvel of simplicity and elegance.” Once Pauline named Worth as its creator, Eugénie requested he see her at the Tuileries the next morning. Thus, Empress Eugénie became Worth’s star client, catapulting him to international acclaim (Trubert-Tollu 33-35).

Fig. 1 - Edouard Dubufe (French, 1819-1883). Eugenie de Montijo de Guzman, Empress of the French, 1854. Oil on canvas; 113 x 97.5 cm. Versailles: Chateau de Versailles, MV 5829. Gift of Baroness Alexandry d'Orengiani, 1920. Source: Chateau de Versailles

Fig. 2 - Franz Xaver Winterhalter (German, 1805-1873). The Empress Eugenie Surrounded by her Ladies in Waiting, 1855. Oil on canvas; 300 × 420 cm (118.1 × 165.4 in). Compiègne: Musée du Second Empire, MMPO 941. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Menswear

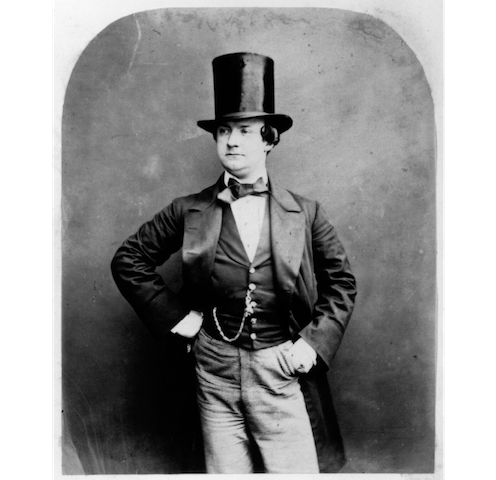

Fig. 1 - Herbert Watkins (British, 1828-1916). Augustus Frederick Glossop Harris, Late 1850s. Albumen print; (7 3/8 in x 6). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG P301(103). Purchase, 1985. Source: National Portrait Gallery

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (Northern Irish). Frock Coat and Trousers, ca. 1852. Wool, linen. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.2010.33.8a-b. Purchased with funds provided by Michael and Ellen Michelson. Source: Los Angeles County Museum of Art

“a growing air of ease, a move towards less restricting, more comfortable clothes.” (32)

The sewing machine, made available for commercial use at the end of the 1840s, led to a huge rise in the availability of ready-to-wear men’s clothing, including everything from shirts to suits and coats (Tortora 358). The production time was dramatically reduced with the sewing machine: A man’s shirt took fourteen and a half hours by hand, but only a little over an hour by machine, while a frock coat could take almost seventeen hours by hand, but two and a half by machine (Severa 92). This abundance of ready-made clothing led to a democratization of fashion in the 1850s and throughout the rest of the century. American newspaper editor Horace Greeley noted in the mid-1850s:

“No distinction in clothing between gentlemen and otherwise can be seen in the United States, as was true of Europe. Every sober mechanic has his one or two suits of broadcloth, and, so far as mere clothes go, can make as good a display when he chooses, as what are called the upper classes.” (Severa 85)

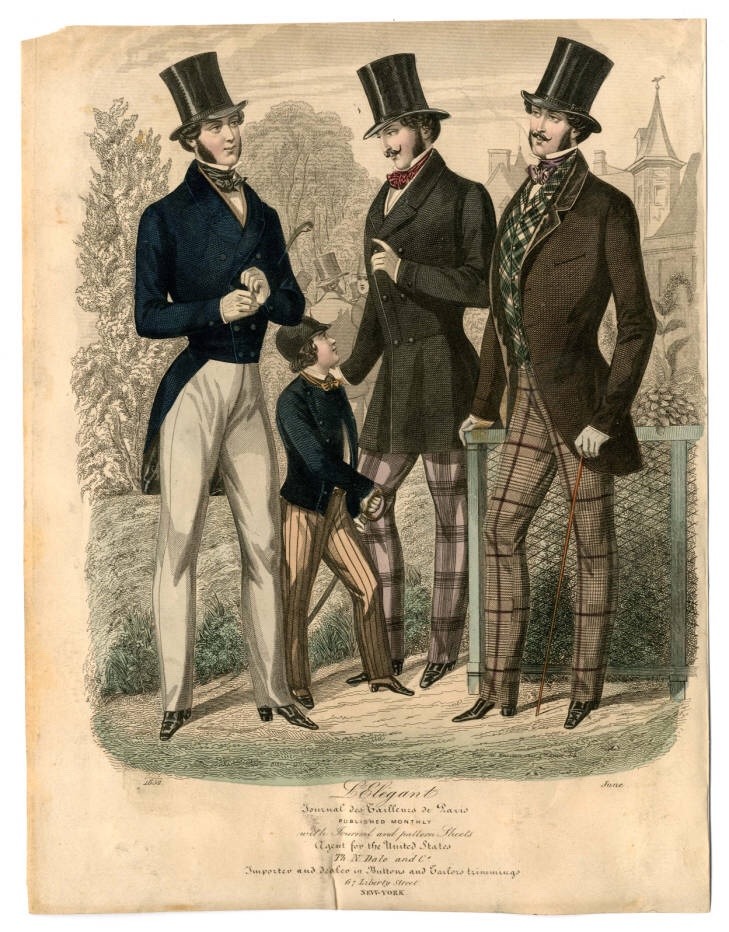

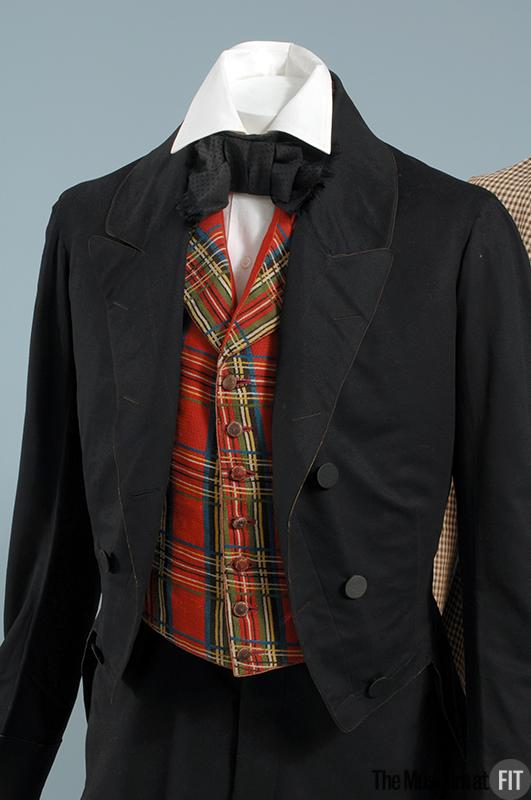

For daytime formal wear, a man usually wore a frock coat (Fig. 2), defined by its waistline seam and full skirts (Cumming 87). An alternative was the morning coat, or cutaway, that also featured a waistline seam, but cut sharply away towards the back; the man at the far right of Figure 3 wears a morning coat. For casual or sporting events, the sack or lounge jacket was a new choice, introduced in the 1840s. Cut straight, without a waist seam, and featuring small lapels, the sack jacket was a comfortable, relaxed alternative that became a staple of the male wardrobe later in the century (Tortora 370; Shrimpton 31-34). Coats, whichever a man chose, were usually made in dark colors, although light linens could be worn in summer. It would be paired with a vest and trousers. Generally, coats and trousers were made in different colors. In fact, plaids and checks remained fashionable for trousers (Fig. 3), although plain black became more common toward the end of the decade. Vests could be made of bright, elaborate silks for dress occasions (Fig. 4), but were frequently seen in dark colors matching the coat (Severa 105). Tailcoats, with a square-cut waist in front and long tails (Figs. 3-4), while still seen as formal daywear in the early 1850s, were relegated to formal evening events by 1860 (Tortora 370).

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown (French). L'Elegant: Men's Fashion Plate, June 1852. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17509853. Gift of Leo Van Witsen. Source: The Met Digital Collections

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (American). Man's Tail Coat, ca. 1850. Wool. New York: The Museum at FIT, 82.33.2. Gift of Robert Riley. Source: The Museum at FIT

Fig. 5 - Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917). Portrait of the Artist, 1855. Oil on paper mounted on canvas; 81.5 x 65 cm. Paris: Musée d'Orsay, RF 2649. Source: Musée d'Orsay

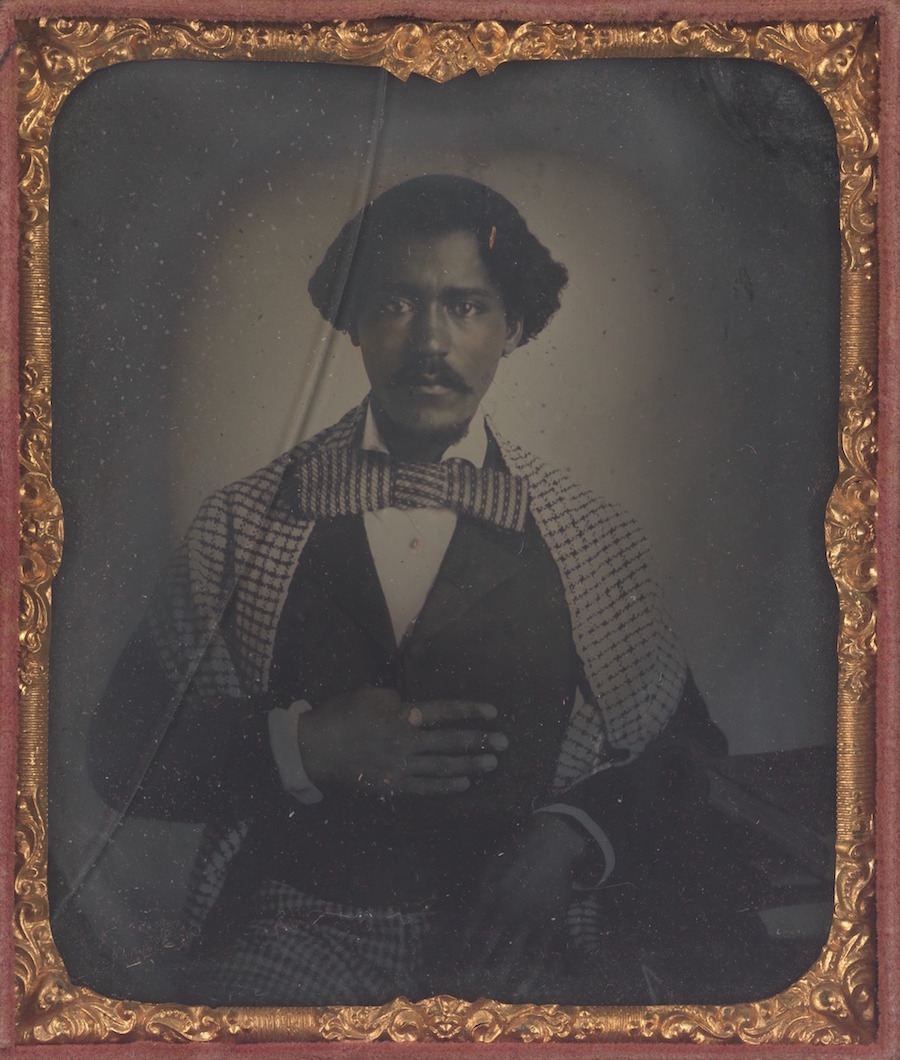

Fig. 6 - Photographer unknown (American). Tintype of John H. Copeland in an embossed leather case, 1850s. Collodion and silver on iron tintype; 9.2 x 8.3 cm. Washington, D.C.: National Museum of African American History & Culture, 2014.174.7.2ab. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Source: NMAAHC

Fig. 7 - J. B. Starkweather (American). Miners in the Auburn Ravine, ca. 1852. Quarter plate daguerreotype. Sacramento: California State Library. Source: California State Library

Shirts were most frequently white, and featured either separate or attached collars. The height of collars lowered, and wide cravats of earlier years were replaced with slim, silk neckties tied in a flat bow (Figs. 5-6) (Shrimpton 32); in the early 1850s, there was a trend for tying bows with one end jauntily extended, creating an asymmetrical effect (Figs. 1-2) (Severa 121). The top hat was, by far, the dominant hat choice for all occasions. The 1850s saw the introduction of a new hat style that would eventually rival the top hat for supremacy later in the century: the hard felt, dome-crowned bowler (Cumming 28). The famous, aristocratic hatter, Locke’s of St. James, introduced the style, and it became an alternative to the top hat for daytime wear in town (Ginsburg 87-88; Hughes 122). For more casual, country wear, the wide-awake hat, a low-crowned, wide-brimmed felt was popular (Tortora 372; Severa 106).

Interestingly, two future powerhouses of American menswear saw their beginnings in the 1850s. Opened in 1818 under a different name, the enterprising menswear company in New York City inspired by the Savile Row tailors of London, changed its name to Brooks Brothers in 1850. It soon adopted its “golden fleece” logo, and made the savvy and forward-thinking choice to begin stocking ready-made clothing for men. Their high quality ready-to-wear menswear became a foundational pillar of American style (Betts 10-11). Meanwhile, across the country in California, during the height of the Gold Rush, a man named Levi Strauss began making work pants for miners out of heavy-duty canvas (Fig. 7). He came San Francisco in 1850 and planned to sell canvas for tents and wagon covers, but discovered the material could hold up to the hard wear of gold mining. Within a few years, he began making his sturdy work pants out of denim, a heavy twill-weave cotton, dyed blue with indigo, and blue jeans were born (Tortora 356; McNeil 331). Strauss’ jeans were a huge success becoming standard work-wear for farmers, miners, and cowboys throughout the nineteenth century, and eventually becoming fashionable everyday wear in the twentieth century.

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Fig. 1 - Designer unknown (American). Child's dress, 1850-55. Wool, silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.927. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

As throughout most of the nineteenth century, babies of the 1850s wore long, white dresses with short sleeves. During this period, though, the dresses became fuller and longer, sometimes up to a yard in length, and more elaborate featuring whitework (Buck 154). When infants reached six to nine months old, they were put into shorter dresses so they could learn to walk. Little boys and girls dressed very similarly as toddlers; both wore short dresses with frilled drawers peeking out underneath. Tiny prints were fashionable for such dresses (Fig. 1) (Severa 107-108). Boys’ dresses were often made in brighter colors such as bold red with black trim (Marshall 23).

Little girls, three to ten years old, wore simplified dresses that mimicked the overall silhouette of adult fashions with an emphasis on the waistline and full skirts. Before mid-decade, the waistline remained lower, as in the 1840s, and then climbed to the natural point (Figs. 2-3) (Severa 152). Dresses were often high-necked loose tops set into a plain waistband with pleated or gathered skirts. A dressier style featured an off-the-shoulder neckline (Fig. 2) (Severa 108; Buck 127). At this stage, little girls wore their hair ear-length, parted in the center, and either combed straight behind the ears or hanging in ringlet curls (Severa 128, 181; Tortora 373).

Fig. 2 - Francis Grice (American). Two Unidentified Young Girls, ca. 1850-55. Daguerreotype; 8.1 x 7 cm. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, DLC/PP-2017:034. Purchase by Lynn Maillet, 2017. Source: Library of Congress

Around eleven or twelve, girls were dressed as miniature adults in dresses that were only differentiated from their mothers by their shortened length that gradually grew to reach their ankles at age sixteen (Figs. 4-5). During this phase, girls began to grow their hair long and put it up into adult styles. They also abandoned the flat-crowned, wide-brimmed hats of childhood for adult bonnets (Buck 243; Severa 108). Long, white pantalettes, frequently with openwork embroidery, could be seen underneath girls’ shortened skirts (Figs. 2, 4) (Laver 178). Girls of all ages wore the requisite petticoats, and late in the decade, older girls even adopted the cage crinoline (Buck 241, 227).

Fig. 3 - Photographer unknown (American). Young African American Girl, ca. 1855. The Kinsey African American Art & History Collection. Source: Black History Album

Fig. 4 - Louis Benlier and Heloise Leloir (French). L'Iris: Children's Fashion Plate, 1858. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17509853. Gift of Woodman Thompson. Source: The Met Digital Collections

Fig. 5 - Leonida Caldesi (Italian, 1823-1891). Princess Helena and Princess Louise with Princesses Clotilde and Amélie of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, April 14, 1859. Albumen print; 14.2 x 19.1 cm. London: Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 2900171. Source: Royal Collection Trust

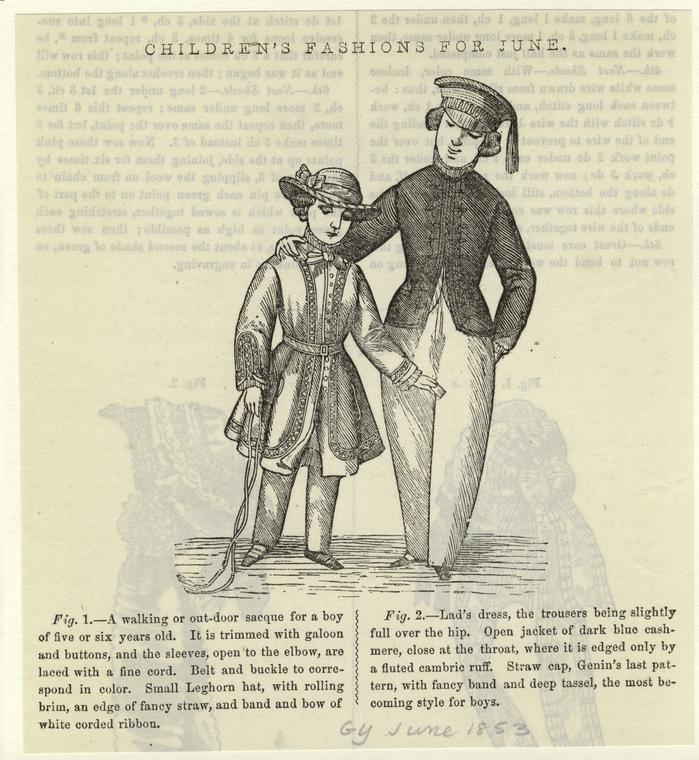

Until about the age of four, boys remained in the dresses of toddlerhood, then they were breeched, or given their first pair of trousers–a rite of passage (Shrimpton 45). After breeching, boys of the 1850s wore long, loose trousers, which were now made with a fly-front, with a long tunic that more closely followed the lines of womenswear than men’s (Buck 222). These tunics were either made in the sacque style, cut loosely from the shoulder and often belted (Figs. 6-7), or more fitted with a set-in waistband (Rose 97; Severa 108, 156). Sometimes, younger boys would persist in wearing frilled drawers with such tunics instead of true trousers (Fig. 7). During this transitional phase between the age of four and ten or eleven, sailor suits, with their distinctive collar, were alternatives to tunics and trousers (Tortora 373). Around eleven, boys could begin to wear trousers, shirts, and jackets. A particularly common jacket type for boys was the roundabout (Fig. 8), a closely-fitted front-buttoning jacket cut to the waist (Severa 547). Young boys wore straw sailor hats with trailing ribbons and various types of caps; a cap with a stiffened peak and decorative tassel hanging to one side was favored (Buck 138). By fourteen years old, boys became young men, and dressed like their fathers (Severa 108).

Fig. 6 - Artist unknown (American). Children's Fashions for June, June 1853. New York: The New York Public Library, PC COSTU-185-Am. Source: The New York Public Library

Fig. 7 - Photographer unknown (American). Thomas Munroe Shepherd at Four Years Old, ca. 1859. Ambrotype. Northampton, MA: Historic Northampton, 59.384. Source: Historic Northampton Online Digital Catalog

Fig. 8 - Designer unknown (American). Boy's Suit, ca. 1855-1860. Silk, cotton. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.6262a, b. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

References:

- Betts, Kate. Brooks Brothers: 200 Years of American Style. New York: Rizzoli, 2017. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1083139481

- Bruna, Denis, ed. Fashioning the Body: An Intimate History of the Silhouette. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/945435796

- Buck, Anne. Clothes and the Child: A Handbook of Children’s Dress in England, 1500-1900. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1996. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/243852072

- Cumming, Valerie ed., The Dictionary of Fashion History. New York: Berg, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1003643284

- Cunnington, C. Willett. English Women’s Clothing in the Nineteenth Century: A Comprehensive Guide with 1,117 Illustrations. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/868281120

- “Eugénie de Montijo.” Chateau de Versailles. http://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/history/great-characters/eugenie-montijo

- Fischer, Gayle V. Pantaloons and Power: A Nineteenth-Century Dress Reform in the United States. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2001. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/918164896

- Foster, Vanda. A Visual History of Costume: The Nineteenth Century. London: BT Batsford, 1984. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/28405843

- Fukai, Akiko, ed. The Collection of the Kyoto Costume Institute: Fashion, A History from the 18th Century to the 20th Century. Kyoto: Taschen, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/81452017

- Garfeild, Simon. Mauve: How One Man Invented a Color That Changed the World. New York: W.W. Norton, 2000. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/881522529

- Ginsburg, Madeliene. The Hat: Trends and Traditions. London: Studio Editions, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/22914760

- Hughes, Clair. Hats. London: Bloomsbury, 2017. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1083133990

- Johnston, Lucy, Marion Kite, Helen Persson, Richard Davis, and Leonie Davis. Nineteenth Century Fashion in Detail. London: V&A Publications, 2005. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/61302743

- Laver, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History, 5th ed. London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/966352776

- Lynn, Eleri, Richard Davis, and Leonie Davis. Underwear: Fashion in Detail. London: V&A Publications, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/929249496

- Marshall, Noreen. Dictionary of Children’s Clothes: 1700s to Present. London: V&A Publications, 2008. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/328862693

- McNeil, Peter and Vicki Karaminas, ed. The Men’s Fashion Reader. Oxford: Berg, 2009. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/892521813

- Metych, Michael. “Sir William Henry Perkin.” Brittanica Online. Last updated July 10, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Henry-Perkin

- Ray, Michael. “Elias Howe.” Brittanica Online. Last updated September 20, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Elias-Howe

- Rose, Clare. Children’s Clothes: 1750-1985. London: BT Batsford, 1989. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/317672212

- Severa, Joan L. Dressed for the Photographer: Ordinary Americans and Fashion 1840-1900. Kent, OH: Kent State UP, 1995. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/552147475

- Seward, Desmond. Eugénie: The Empress and Her Empire. London: Thistle Publishing, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/923889871

- Shrimpton, Jayne. Victorian Fashion. Oxford: Shire Publications, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/896980798

- Thieme, Otto C., Elizabeth A. Coleman, Michelle Oberly, and Patricia Cunningham. With Grace and Favor: Victorian & Edwardian Fashion in America. Cincinatti: Cincinatti Art Museum, 1993. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/260147672

- Tortora, Phyllis G. and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume, 5th ed. New York: Fairchild Books, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/865480300

- Trubert-Tollu, Chantal, Françoise Tétart-Vittu, Jean-Marie Martin-Hattemberg, and Fabrice Olivieri. The House of Worth 1858-1954: The Birth of Haute Couture. London: Thames & Hudson, 2017. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1027406188

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1850-1859

Rulers:

- England: Queen Victoria (1837-1901)

- France: Napoleon III (1852-1870)

- Spain: Queen Isabella II (1833-1868)

- United States:

- Millard Fillmore (1850-1853)

- Franklin Pierce (1853-1857)

- James Buchanan (1857-1861)

Events:

- 1850 – The Compromise of 1850 establishes California as a free state and re-organizes the Mexican Cession in the Utah Territory and the New Mexico Territory.

- 1851 – The Great Exhibition is held in the Crystal Palace in London. It was a hugely successful celebration of the world’s cultural and technological innovation in the wake of the Industrial Revolution.

- 1851 – Napoleon III seizes power in a coup d’état in France, becoming Emperor of the Second French Empire.

- 1852 – The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine is published, including advice on needlework from domestic writer Mrs. Beeton.

- 1852 – Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin is published.

- 1853-1855 – The Crimean War is fought between the Russians and the British, French, and Ottoman Turkish.

- 1854 – With the birth of photography comes the carte de visite, a fashionable visiting card that includes a photograph of the traveler. Immense popularity leads to the publication of the cards of prominent figures, whose fashions are followed.

- 1859 – Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species is published.

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Fashion Plate Collections (Digitized)

- Costume Institute Fashion Plate collection

- Casey Fashion Plates (LA Public Library) - search for the year that interests you

- New York Public Library:

NYC-Area Special Collections of Fashion Periodicals/Plates

- FIT Special Collections (to make an appointment, click here)

- Journal des demoiselles (vol. 19-60, 1851-1892, with gaps) – AP20.J76

- Costume Institute/Watson Library @ the Met (register here)

- New York Public Library

- Brooklyn Museum Library (email for access)

Fashion Periodicals (Digitized)

Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Secondary Sources

Also see the 19th-century overview page for more research sources... or browse our Zotero library.