Chantilly lace is a kind of bobbin lace popularized in 18th century France. It is identifiable by its fine ground, outlined pattern, and abundant detail, and was generally made from black silk thread.

The Details

C

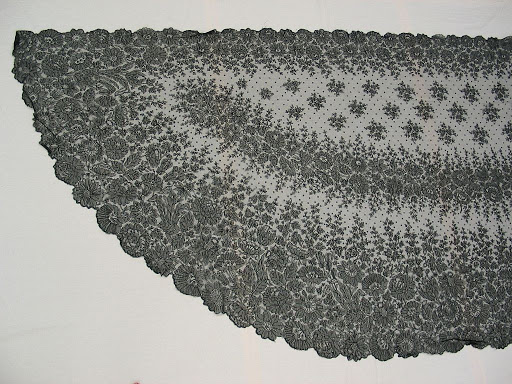

hantilly lace is a relatively new style of lace, originally made by bobbins rather than needles. It is a French style that flourished in the mid-eighteenth century (Fig. 1) and was usually made in black silk thread (Fig. 2) (Earnshaw 96). Other bobbin laces, like Torchon and Genoese, came to popularity in earlier centuries and were often made of linen. French silk lace is often referred to as ‘blonde’ lace, due to the natural color of silk (Earnshaw 16-17).

In Antique Lace, Identifying Types and Techniques (2002), Heather Toomer lays out a clear set of characteristics for identification:

“1. Straight bobbin lace, usually in dull black silk (grenadine) thread but sometimes in ivory.

2. Half stitch pattern areas.

3. Thick gimp outline to the pattern usually formed by a bundle of threads.

4. Splits often found in large pieces – these form along joins between pattern pieces.” (212)

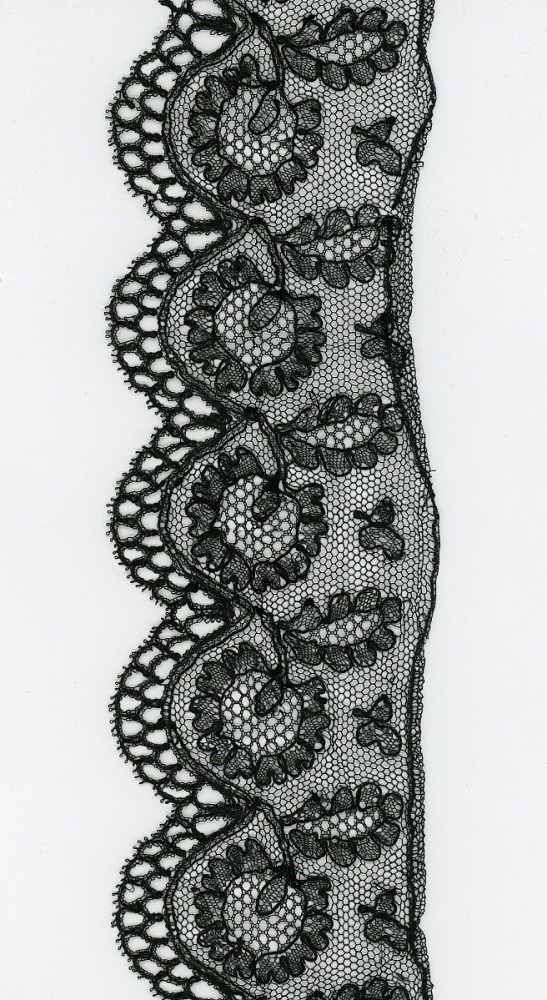

Toomer also describes the two styles of hexagonal ground, (the pattern or mesh that fills in large areas) that are used in the creation of this lace:

“Chantilly ground (kat stitch, point de Paris). The meshes give the appearance of a six-pointed star, with pairs of twisted threads defining a central hexagonal hole surrounded by six smaller triangular holes.

Fond simple (East Midlands point ground, Lille ground). Hexagonal mesh with four sides of two twisted threads and two sides of two threads crossed. This is more common in the second half of the 19th century.” (212)

Fig. 1 - Jean-Etienne Liotard (Swiss, 1702-1789). Portrait de Madame Jean Tronchin, née Anne de Molesnes, 1758. Paris: Musée du Louvre. Photo (C) RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Michel Urtado. Source: RMNGp

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown. This Black Chantilly lace lappet or scarf is a sample of early Victorian bobbin lace from about 1870. It is of good quality, but fragile. The fine black silk threads are disintegrating. The ends are of higher quality than the center section., 1860-1870. Silk. American History Museum, Washington DC: National Museum of American History. Source: National Museum of American History

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (Belgian). Black Chantilly lace drawers, ca. 1925. Machined chantilly silk lace. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, BK-1997-82-B. G.A. Brusse-Urtebise Bequest, Amsterdam. Source: Rijksmuseum

Fig. 4 - Maker unknown. Chantilly lace mantilla, 1890. Silk. New Zealand: Museum of New Zealand. Source: Museum of New Zealand

In Lace: Its Origin and History (1904), Samuel L. Goldenberg sheds light on the style, which has been used on everything from shawls to underwear (Fig. 3):

“Chantilly.—One of the blonde laces, of the sort recognizable by their Alençon réseau ground and the flowers in light or openwork instead of solid. It is made both in white and black silk. Black Chantilly lace has always been made of silk, but a grenadine, not a lustrous silk. The pattern is outlined with a cordonnet of a flat, untwisted silk strand.” (35)

Goldenberg describes that it was established in the seventeenth century by the Duchess of Longueville in Chantilly near Paris, but the French Revolution in the 1790s destroyed the industry (35). It was resucitated in the early nineteenth century but had to move away from Chantilly due to costs:

“The supremacy of lacemaking formerly enjoyed by Chantilly has now been transferred to Calvados, Caen, Bayeux and Grammont. The widely-known Chantilly shawls are made at Bayeux, and also at Grammont.” (35)

Keep in mind that he published this more than a century ago, however, and lace is no longer held to the same standards, nor made in the same locales by experts. The Chantilly lace that he was familiar with (Fig. 4) was still good quality in comparison with modern fast-fashion examples.

Fig. 5 - Maker unknown. Chantilly lace, 1800s. Silk. New Zealand: Museum of New Zealand. Source: Museum of New Zealand

While a key sign of Chantilly lace is that it is made of black silk, the structure is what actually makes it Chantilly, and thus white and ‘blonde’ examples do exist (Fig. 5). In The Identification of Lace (2009), Pat Earnshaw elaborates more on the history, structure and look of lace:

“This was a mainly black lace, though white examples are known dating from the early nineteenth century. It is said that production flourished between 1740 and 1785 when it was under patronage of Louis XV (1715-74) and Louis XVI (1774-93), but few eighteenth-century examples have been identified. This may be because the black dye which was used was acid and contained iron. It tended to oxidise, lose its color and rot the fabric.” (96)

This is an example of ‘inherent vice’, which means that the method used to make an object contributes to its destruction. Many textiles made with iron-based black dye suffered the same fate, which is why we have so few of them. Black Chantilly lace shawls were extremely popular in the mid-19th century (Fig. 6), and various other types of headdresses were created with it in earlier decades (Fig. 7). Earnshaw goes on:

“Like other French laces it declined with the Revolution (1789-95), but it was revived about 1804 by the Emperor Napoleon I, who decreed that only Alençon and Chantilly laces should be worn at court. It was made of varying qualities until Edwardian times… similar if rather coarser laces were still produced elsewhere, for example at Calvados, Caen, Bayeux and Le Puy and also a form of not very good quality in Buckinghamshire, where it was known as ‘Amersham Black.'” (96)

The twentieth century represented the demise of traditional lace. While machine-made lace had been available in some form since at least 1809, it was only in the early nineteen hundreds that it was far more cost- and quality-effective to create lace by machine rather than by hand (“Lace: A Sumptuous History”). Gone were the days of hand-made lace mantles (Fig. 8) or fine detailing on gowns (Fig. 9). Earnshaw describes the kinds of garments that were popularly made of Chantilly lace before the Edwardian era:

“[T]he possible width of each strip was limited by the size of the pillow and the difficulty of manoeuvring the bobbins; thus… large items such as stoles, capes or shawls had to be made of smaller pieces invisibly stitched together. Even fascinators, fall caps and fan leaves required some joining. The main designs were floral, with pleasantly naturalistic roses, tulips, daffodils and irises, with swags and ribbons, and occasionally birds, putti or grape and vine leaves with tendrils.” (96)

Lastly, Earnshaw details the fibers and construction of this kind of lace, as well as its ground (toile):

“The earlier Chantilly was made of flax but all the later was of a dull grenadine silk stiffened with gum arabic. The toile was usually of halfstitch and was continuous with the fond simple, or occasionally Point de Paris, reseau. The gimp consisted of several strands of flat untwisted silk.” (96)

The hexagonal halfstitched toile (ground) is clearly seen in figure 10.

Santina M. Levey writes in Lace, A History (1983) about Chantilly lace and the influence of Belgian grounds in the nineteenth century:

“During the 1840s, as the market for larger costume items grew, the Chantilly workers copied the Brussels lace-makers and began to join together strips of lace with the invisible stitch known as point de raccroc… The line of the join was none the less a line of weakness, the linking stitch sometimes coming undone to leave a slit in the fabric.” (89)

Levey also makes note of its presence at Britain’s Great Exhibition in 1851, and the spread of mechanization in the later part of the century:

“The Exhibition report… commented on the decline in the making of blonde lace at the three centers but noted of the black lace that that made in Chantilly itself was ‘less intended for general use than to satisfy the desires of the luxurious, being laces of the very finest textures and most beautiful patterns.’ The ability of the lace manufacturers to combine technical quality with good design was to be of increasing importance during the second half of the nineteenth century as competition from the machines increased.” (89)

Fig. 6 - Charles Nègre (French, 1820-1880). Portrait of an unknown woman in front of a background cloth, 1860-1865. Albumen print; 9.2 × 16.1 cm. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, RP-F-2002-27. Source: Rijksmuseum

Fig. 7 - Francisco Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828). Mourning Portrait of the Duchess of Alba, or The Black Duchess, 1797. Oil on canvas. New York: Hispanic Society of New York. Source: The Hispanic Society of America

Fig. 8 - Diego Velázquez (Spanish, 1599-1660). Lady with a Fan, 1640. Oil on wood. London: Wallace Collection. Source: The Wallace Collection

Fig. 9 - Designer unknown (American). Woman's dress: Bodice, Skirt, and Belt, 1866-68. Magenta silk satin with black silk satin and black cotton lace; waist 58.4 cm (23 in). Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1997-80-1a--c. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. W. W. Keen Butcher, 1997. Source: PMA

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown (American). Black Chantilly Bobbin Lace Border, ca. 1830. Washington, D.C.: National Museum of American History, T14484.000. Mrs. Heloise Durant Seeley. Source: National Museum of American History

Its Afterlife

T he luxury boom of the late 1990s and early 2000s revived the demand for lace. Today, Chantilly lace continues to adorn outfits of the elegant and street-fashionable alike, whether as a punk accompaniment (Fig. 11) or layered on designer ready-to-wear on catwalks around the world (Fig. 12).

Fig. 11 - Punk Rave (Swiss, Founded 2008). Night forest lace skirt, ca. 2018. Lace, elastic, zipper. Source: Tragic Beautiful

Fig. 12 - Tom Ford for Yves Saint Laurent (American, 1961-present). Saint Laurent RTW, Fall 2002. Photo Antoine de Parseval. Source: Vogue

References:

- Earnshaw, Pat. The Identification of Lace. Botley, Oxford: Shire Publications, 2009. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/558578337

- Goldenberg, Samuel L. Lace, Its Origin and History. New York, NY: Brentano, 1904. Worldcat / Project Gutenberg

- “Lace: A Sumptuous History: 1600s–1900s.” San Francisco Airport Museum, Feb 5, 2014. Accessed 16 June 2020. SFO Museum

- Levey, Santina M. Lace: A History. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1983. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/898775723

- Toomer, Heather. Antique Lace: Identifying Types and Techniques. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Pub Ltd, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1023220167