Tissot paid close attention to dress details, but his habit of adding a personal flair into the design sometimes rendered his paintings somewhat out-of-step with contemporary fashion trends.

About the Artwork

E

vening, originally titled The Ball, was created in 1878 by French painter and illustrator Jacques Joseph (James) Tissot (Fig. 1). Tissot was born in Nantes, France in 1836 and had a religious upbringing. He traveled to Paris to study at the famous Ecole de Beaux-Arts after he turned twenty, and in less than three years he had shown his work at the Paris Salon. He swiftly gained notice in the art world for his modern genre paintings and portraits, which focused on observing the mannerisms and fashions of the wealthy people of Paris (Warner 236).

He eventually moved to London and began contributing weekly caricatures to Vanity Fair. While he declined his fellow artist Degas’ invitation to participate in the first Impressionist exhibition, Tissot received high praise at Royal Academy of Art events and was commissioned to paint many leading figures in England (Warner 236). During this time, Tissot met his mistress and muse Kathleen Newton, who inspired many of his paintings.

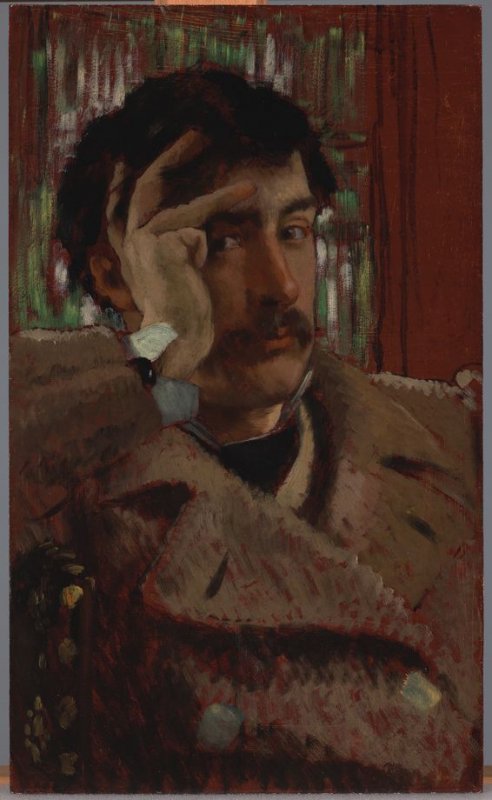

Fig. 1 - James Tissot (French, 1836-1902). Self Portrait, ca. 1865. Oil on panel; 49.8 x 30.2 cm (19 5/8 x 11 7/8 in). San Francisco: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, 1961.16. Source: FAMSF

Evening (Fig. 2) focuses on a young social climber – with the face of Tissot’s mistress – being escorted into a ball by a much older man. The only characteristic we see of the man is his back; white hair and plain black garments are visible, giving the impression that the man is only there to help the young woman with her goals (Groom & Brevik-Zender 183).

Tissot is known for focusing on the daily lives of privileged classes and sometimes poking fun at them. In James Tissot, Russell Ash noted that during the time of the Industrial Revolution,

“The newly rich in particular found themselves uncertain of their place within a much older class structure, nervous about their elevated status and often ill at ease in the social gatherings in which they found themselves.” (9)

This statement is revealing for this painting. While the older man seems to be looking forward with confidence and comfort as they walk in, the woman seems to be unsure of the situation and surveying the view. This represents her nervousness at participating in such a formal event.

This young woman is dressed in a fitted princess-line gown, with pleats galore and white embroidered insets, that shows off (or perhaps creates) her curves. Her fan is open in front of her and attracting attention, signalling that she can hide herself from the viewer but is choosing not to do so. While eye-catching, her dress is modest compared to the older woman in the background, who has bared her decolletage and arms in a dress that is a few years old. While none of the men are visibly looking at the young woman in yellow, the other young woman in the background is looking over at her – possibly contemplating whether or not she is a threat to her chances that night (Groom 183).

Evening is one of fifteen works of art that Tissot created in a series called “La femme à Paris.”

James Tissot (French, 1836-1902). Evening, 1878. Oil on canvas; H. 90; W. 50 cm. Paris: Musée d’Orsay, RF 2253. Source: Musée d’Orsay

About the Fashion

K

nown for documenting the demanding wardrobes of the wealthy, Tissot tended to mix current fashion trends with unique ideas of his own. This aspect of his work has been both criticized and praised, and probably grew out of his childhood around parents who both worked with fabric and fashion. In Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity (2012), Gloria Groom, discusses the success of Tissot’s clothing design in the painting titled Evening and explains that the gown:

“with its tight princess bodice and low, abundantly flounced and pleated train, was hailed as ‘worthy of Worth’; one critic predicted its pleasing trims and colors would be an inspiration to dressmakers.” (183)

Tissot recreated the same scene in a later version of this painting, titled L’Ambitieuse (Fig. 2), and made similar design choices for the dress of the young woman, this time in pink. Her gown has stacks of layered, pleated flounces towards the hem, she is holding a large fan open away from the viewer, the dress’ folds are positioned around the edge of the frame in the same way, and she has the same high neckline in her gown. Russell Ash states:

“To modern viewers the woman’s dress is a sumptuous creation, but Tissot’s contemporaries criticized it for being outmoded, La Vie Parisienne declaring, ‘She can’t aspire to being described as elegant, wearing one of those pink dresses that you wish would finish but never do, of antiqued cut, without any bustle but with a pointed black girdle like those worn twenty years ago.’” (Plate 39)

Indeed, some of the choices Tissot made in depicting the garment in L’Ambitieuse were not in style at the time; by 1883-85 when it was painted, large, protruding bustles had become the fashion, and frothy, light garments like this one had been left behind several years before. To be properly fashionable for 1883-85, the woman in pink would have had to have a silhouette like that of the woman in figure 3, among other elements.

In Evening, the woman in yellow is wearing a gown that draws the eye all around, especially when compared to those in the background. Her gown is made of layers and layers of pleated, multi-colored flounces that seem to gather into the center at the back of her legs. Flounces used as trims towards the hem of the dress were common around 1878. The blue gown in figure 4 has four small rows of tight, pleated flounces around its hem, and the same sort of design around the low posterior that draws the eye past the waist and down. Although this dress was probably worn during the day rather than to an evening ball, an article in Harper’s Bazar from that year talks about the new trends of pleated flounces:

“To trim the foot of silk skirts a new fancy is to make a flounce on a cluster of ten or twelve knife pleats, then put three box pleats each an inch wide, and again a knife-pleated cluster. Such flounces are from six to eight inches deep when finished, are cut straight across the silk, and it is quite the custom to hem the edges on the sewing-machine, though many of the best dress-makers prohibit the use of machine sewing on any part of a silk dress where this sewing is visible.” (219)

Variations on these flounces were common, and Tissot chose to add dozens of extra layers, both white and yellow, of this fashionable trim. It was his way of following a trend but adding his own flair–he had a particular love of yellow and white which is evident here.

Another trend that Tissot depicted in Evening was the combination of multiple fabrics in one garment. It was still quite common during this time to have a dress made entirely of one fabric, as with the blue silk taffeta gown in figure 3. The yellow dress was probably envisioned to consist of a gold silk satin, lighter yellow silk taffeta or yellow cotton organdy, and ivory embroidered cotton insets. In comparison, figure 5 mixes multiple tones and patterns of gold and cream silk along with beaded fringe. A Harper’s Bazar article from later the same year touches on this style of combination:

“Two or three materials appear in a single dress. Thus a costume of India cashmere in plaids of prune and bronze shades will be combined with prune-colored silk and bronze velvet… An elegant dress of brocaded satin, with hazel brown ground and quaint-looking flowers of pale blue, bronze, and Jacqueminot red, is trimmed with bronze satin and velvet.” (571)

But Tissot did not simply follow fashion plates; he always imparted his own touch. It was not the fashion to have a long-sleeved chemisette layered underneath an evening dress; normally, most of a woman’s arms and part of her chest would have been exposed. Yet both the pink and yellow women are covered up. The women in the background of both of his paintings, however, have modishly exposed arms and chests according to the cuts of their gowns. The fashion plate in figure 6 shows a more common neckline for evening gowns of this time.

Tissot is not completely off-trend with the gown’s neckline; this high-collared cut was common for daywear. It seems out of place in this situation, and almost as if she is shielding herself from the many eyes upon her. With the addition of the small hat perched on top of her hair, it looks like she perhaps wandered in wearing a dress from earlier in the day.

An afternoon dress from 1878-80 with a similar cut, more subdued to serve the occasion, can be seen in figure 7. The dress in Evening, while fabulous to modern eyes, at the time would have been a fashion faux pas for such an occasion–as the contrast between the figure in yellow and the other women suggests.

Fig. 2 - James Tissot (French, 1836-1902). L'Ambitieuse, 1883-1885. Oil on canvas; 142.24 x 101.6 cm (56 x 40 in). Buffalo: Albright-Knox Art Gallery, 1909:10. Gift of William M. Chase, 1909. Source: Albright-Knox Art Gallery

Fig. 3 - Mme. Delaunay (French). Magasin des demoiselles: Toilettes de mariée et de cérémonie, 10 March 1885. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17509853. Gift of Woodman Thompson. Source: Watsononline

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (probably American). Dress, ca. 1878. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982.528.4. Gift of Mrs. Charles C. Paterson, 1982. Source: MMA

Fig. 5 - Maison Cecile Laisne (French). Dress, 1878-79. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.45.38.1a, b. Gift of Mrs. Ida Ribera, 1945. Source: MMA

Fig. 6 - Artist unknown (French). Journal des Demoiselles et Petit Courrier des Dames reunis, February 1878. Los Angeles: Casey Fashion Plates, Los Angeles Public Library, rbc6057. Source: TESSA

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown (British). Afternoon dress, 1878-80. Wool and embroidered silk satin. Manchester: Manchester City Galleries, 1947.4118. Source: MCG

Diagram of referenced dress features.

Source: Author

References:

- Ash, Russell, and James Jacques Joseph Tissot. James Tissot. New York: H.N. Abrams, 1992. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/925188690

- Groom, Gloria, and Heidi Brevik-Zender. Impressionism, Fashion & Modernity. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/878842920

- “New York Fashions.” Harpers Bazar XI, No. 14 (April 6, 1878): 219. http://hearth.library.cornell.edu/cache/4/7/3/4732809_1448_014/00000197.tif.1.pdf

- “New York Fashions.” Harpers Bazar XI, No. 36 (September 7, 1878): 571. http://hearth.library.cornell.edu/cache/4/7/3/4732809_1448_036/00000549.tif.1.pdf

- Warner, Malcolm, Anne Helmreich, and Charles Brock. The Victorians: British Painting, 1837-1901. London: Harry N. Abrams, 1997. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/59600277