OVERVIEW

Women’s bodices elongated in the 1650s coming to a point in the front, but in general evolved only slowly from the fashions of the previous decade; whereas men’s doublets shrunk radically and their breeches expanded, becoming heavily ornamented with ribbon loops. With England under Cromwell’s control, France takes the lead in fashion.

Womenswear

Women’s fashions in the 1650s continued trends of the previous decade; off-the-shoulder necklines, shimmering satins, lace collars and cuffs, and decorative metallic lace trim all remained popular at the start of the decade. Maria Euphrosyne (Fig. 1), sister of King Charles X of Sweden, exemplifies these earlier styles in her 1653 portrait. Indeed, as François Boucher notes in A History of Costume in the West (1997), women’s dress did not change as dramatically as menswear did in this same period (258). The changes that did occur were incremental evolutions of previous styles:

“The boned bodice was stiff, tight-fitting and lengthened in front into a point: the short, full sleeves showed the chemise sleeves, which were likewise full and finished with lace flounces.” (Boucher 259)

Euphrosyne’s more fashion-forward fellow Swede, Jeanne Parmentier (Fig. 2) demonstrates these new trends with her long, pointed bodice with short bodice sleeves and lace cuffs. She also wears her hair flat on the top with long, dense ringlets on either side of her face—a hairstyle that will only grow in popularity. As in the 1640s, a pearl necklace—sometimes with a matching pair of pearl bracelets—was considered the perfect accompaniment to any look.

A portrait of Odilia van Wassenaar (Fig. 3) shows that these new styles extended even to the Netherlands, which had long lagged in adopting European dress trends. But, as Daniel Delis Hill notes in his History of World Costume and Fashion (2011): “The last of the cartwheel ruffs finally vanished by the 1650s even in Holland and Germany” (411). Van Wassenaar wears the long, pointed bodice that gives her torso an elongated look; it would have been worn over a simple chemise (called a smock or shift in England). The bodice itself was boned in this period so no additional stays or corset needed to be worn. Skirts were full, featuring many cartridge pleats at the waist to create the volume—this can be seen in the portraits of both Parmentier and van Wassenaar (Figs. 2-3). These skirts were separate from the bodice and hung naturally from the waist without rigid understructures like the farthingales seen in the 16th century, though a bum roll would often be tied on to create a bit of fullness and attractively set off the narrow waist.

While the upper torso appeared rigid, the lower half was more fluid in strong contrast to the fashions in 1650s Spain, where the farthingale was still worn at court. As Velázquez’s portrait of the Infanta Maria Teresa (Fig. 4) attests, the farthingale in this period had become very elliptical, creating an incredibly wide silhouette; the bodice now extended down over the farthingale in a large peplum. Maria Teresa in 1660 will undergo a dramatic style transformation when she marries King Louis XIV and becomes Queen Consort of France, adopting French-style dress.

Fig. 1 - Hendrick Munnichoven (Swedish, -1664). Portrait of Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie with his wife Maria Euphrosyne, 1653. Oil on canvas; 219 x 201 cm (86.2 x 79.1 in). Mariefred, Sweden: Gripsholm Castle. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 2 - Bartholomeus van der Helst (Dutch, 1613-1670). Jeanne Parmentier, 1634-1710, gift De Geer, 1656. Oil on canvas; 110 x 91 cm. Stockholm: Nationalmuseum, NMLeu 22. Source: NM

Fig. 3 - Abraham van den Tempel Leeuwarden (Dutch, 1622-1672). Portrait of Odilia van Wassenaar, 1655. Oil on canvas; 122.9 x 94.3 cm. Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1953.1080. Source: MBAM

Fig. 4 - Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (Spanish, 1599-1660). Infanta Maria Teresa (1638-1683), 1652-53. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie, 353. Source: KHM

Fig. 5 - Charles Beaubrun and Henri Beaubrun (French, 1604-1692 and 1603-1677, respectively). Portrait of a Lady called Jeanne de Marigny, 1650-60. Oil on canvas; 128 x 84.5 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 566-1882. Bequeathed by John Jones. Source: V&A

Fig. 6 - Gerrit van Honthorst (Dutch, 1590-1656). Portrait of Mary, the Princess Royal (1631-1660), ca. 1655. Oil on canvas; 112 x 89.6 cm (44 x 35 1/4 in). Geneva: Private Collection. Source: Historical Portraits

Fig. 7 - Gerrit van Honthorst (Dutch, 1590-1656). Probably Mary, Princess Royal and Princess of Orange, 1650s. Oil on canvas; 106 x 88.3 cm (41 3/4 x 34 3/4 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 1534. Source: NPG

Fig. 8 - Gerard van Honthorst (Dutch, 1590-1656). Portrait of Elisabeth van Nassau-Beverweerd (1633-1718), 1651. Oil on panel; 73 x 57 cm. The Hague: Netherlands Institute for Art History, 37342. Source: RKD

Indeed, France dominates fashion in the second half of the 17th century—a leadership they would retain in womenswear arguably up to the present day. England was in no position to challenge them as “about 1650 … Puritan styles, already worn among the middle classes, were imposed on society at large by the austere government of Cromwell” (Boucher 273). In a portrait of Jeanne de Marigny (Fig. 5), we see the same pointed bodice and short, off-the-shoulder sleeves adopted in Sweden; as Millia Davenport notes in The Book of Costume (1948): “The neckline of the bodice becomes wider, more horizontal and tends to slip off the shoulders.” (519) But in France the lace at the neckline and cuffs has been abandoned in favor of nearly translucent gauzy fabric: “a simple swathe of linen along the necklines marks the move away from heavy lace collars” (Cumming 88).

Mary Stuart, Princess Royal and Princess of Orange, dresses in her 1640s style [see “Fashion Icon” section below] in a portrait by Gerrit van Honthorst (Fig. 6), but soon adopted these new French style trends (her mother, Henrietta Maria, was French—see “Fashion Icon” in the 1630-1639 overview). Note the small dog in the portrait, which became a common companion in female portraits of this period (see also Figs. 1, 3, 14). In this case the dog has added significance as it’s a “King Charles spaniel…a favourite breed of Charles II and his sister Henrietta Anne, and became almost symbolic of that generation of Stuarts” (Mould).

A later portrait thought to be of Mary (Fig. 7) shows her now with the same gauzy fabric edging the neckline of her very low-cut bodice, which comes to a point in the front, just as de Marigny’s does (Fig. 5). Also as Valerie Cumming notes in A Visual History of Costume: The Seventeenth Century (1984): “The rigid line of the bodice was softened by fuller sleeves in the 1650s,” as in this portrait (88). Note that the sheer fabric is pinned to the center front of the bodice with a jeweled brooch as was common at the time; another example can be seen in the portrait of Elisabeth van Nassau-Beverweerd (Fig. 8).

As discussed above, bodices and skirts were separate in this period and so didn’t always need to coordinate, though they typically did in portraiture. A genre scene by Gerard ter Borch the Younger (Fig. 9) shows us a young Dutch woman in a pink skirt paired with a cream bodice with the sleeves attached via green ribbons. Her hair is up in a simple cap. The side view offered allows us to just make out that her bodice is laced up the back, as indeed all these boned bodices were in the period.

Fig. 9 - Gerard ter Borch the Younger (Dutch, 1617-1681). A Young Woman at Her Toilet with a Maid, 1650-51. Oil on wood; 47.6 x 34.6 cm (18 3/4 x 13 5/8 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 17.190.10. Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917. Source: MET

Fig. 10 - Hendrik Munnichhoven (Swedish, -1664). Beata Elisabeth von Königsmarck (1637–1723), 1654. Oil on canvas; 104 x 90 cm (40.94 x 35.43 in). Skokloster, Sweden: Skokloster Castle, SKO 3038. Source: LSH

Fig. 11 - Joan Carlile (British, c. 1606-79). Portrait of an Unknown Lady, 1650-55. Oil on canvas; 110.7 x 90 cm. London: Tate Britian, T14495. Presented by Tate Patrons 2016. Source: Tate

Ribbon embellishments were becoming more and more popular for men’s and women’s wear as can be seen in the portrait of Beata Elisabeth von Königsmarck (Fig. 10). Her silver satin bodice has decorative blue-ribbon closures along the center front, which coordinates with the blue scarf that edges her neckline and similar ribbons gathering her full sleeves at the elbow.

In England, styles of the 1640s continued as in Joan Carlile’s portrait of an unknown woman (Fig. 11)—Carlile is notable as one of the first British women artists to paint professionally in oil. The shimmering off-the-shoulder satin bodice is extremely low-cut, and she holds a sheer scarf in her right hand. The portrait is somewhat unusual in that it reflects the rigid line fashionable at the time; it had become quite common to be painted instead in classicized, draped versions of informal dress of the day. Dutch painter Peter Lely specialized in this sort of drapery painting and produced countless versions of it for British aristocrats (Figs. 12-14).

Lely’s portrait of Elizabeth Murray, Lady Tollemache (Fig. 12) depicts her in a brown satin gown that mimics the lines of fashionable dress, but softens them, with no boning apparent in the bodice. She is perhaps meant to be wearing a nightgown, an informal, comfortable style of dress worn without stays (though not worn to sleep in), here accessorized with a blue satin scarf wrapped around her shoulders. Notably Lely depicts a young black servant, whose identity is now lost, alongside Murray, proffering her a platter of roses. The servant is dressed in a blousy striped shirt and wears a prominent large pearl earring in his left ear. It’s possible the young man is a slave as slavery was technically legal in England until 1772, though Britain also had long had a small free black population. It became quite common to feature black slaves or servants alongside white women in 17th-century portraiture (see another example in the “Fashion Icon” section below and in subsequent decade overviews).

Fig. 12 - Peter Lely (Dutch, 1618-80). Elizabeth Murray, Lady Tollemache, later Countess of Dysart and Duchess of Lauderdale (1626-1698) with a Black Servant, ca. 1651. Oil on canvas; 124 x 119 cm. Greater London: National Trust, Ham House, 1139940. Source: National Trust

Fig. 13 - Peter Lely (Dutch, 1618-180). Mary Capel (1630–1715), Later Duchess of Beaufort, and Her Sister Elizabeth (1633–1678), Countess of Carnarvon, ca. 1652-62. Oil on canvas; 130.2 x 170.2 cm (51 1/4 x 67 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 39.65.3. Bequest of Jacob Ruppert, 1939. Source: MET

Fig. 14 - Peter Lely (Dutch, 1618-1680). Sir Thomas Fanshawe of Jenkins (1628–1705), and His Wife, Margaret (1635–1674), 1659. Oil on canvas; 135 x 169 cm. London: Valence House Museum, LDVAL10. Gift from Aubrey Fanshawe, 1963. Source: ArtUK

Mary and Elizabeth Capel (Fig. 13) are swathed in shimmering drapery in Lely’s characteristic style, but one that would not be seen in daily life. As the Metropolitan Museum of Art notes, he:

“pays tribute both to the sitters’ beauty and their accomplishments. Mary, on the left, would become a major patron of botanical research, while Elizabeth displays one of her own flower paintings on the right.”

Margaret Heath appears even more informally in a very loose silver gown, with a draped purple cape, small dog and a pile of roses on her lap (Fig. 14). Her husband’s dress, beyond the billowing sleeve of his white shirt, is also obscured by a black cape or drapery. Thus portraiture becomes an increasingly unreliable guide to fashionable dress in the seventeenth century.

Fashion Icon: Mary Stuart, Princess Royal & Princess of Orange

Mary Stuart was the eldest daughter of King Charles I of England and Henrietta Maria of France. She was the first to hold the title of Princess Royal. She became Countess of Nassau upon her marriage to William II of Orange, when she was nine and he was fifteen. Three years later, in 1644, she moved to the Netherlands. According to the National Portrait Gallery, “Mary was distinguished as a young girl for her intelligence and beauty.”

In 1647 after his father’s death, William II became the stadholder; a portrait from that same year shows the teenage couple (Fig. 1) with Mary in a bright yellow satin dress with low-cut bodice and full, elbow-length sleeves. The dress was either popular with Mary or with portraitists as she was also painted in a green (Fig. 2) and red version (see Fig. 6 above).

Tragically William II, only 24 years old, died of smallpox in November 1650 and the couple’s only child, Willem, was born a few days later. Mary, now a widow at age 19, became Dowager Princess of Orange and co-regent for her son, who had immediately become Prince of Orange as his father was dead. She would serve as co-regent until 1660.

A 1652 portrait depicts her as Princess of Orange and widow of William II (Fig. 3). As the Rijks Museum explains:

“White is the colour of mourning for people of royal blood. Mary was already a widow by the time she turned 19. Her husband, the Stadtholder William II, died in 1650 of smallpox. Two years later she had herself portrayed as his widow, holding an orange in her hand as a reference to the House of Orange. At the left is the stadtholders’ gate of the Binnenhof with a view of The Hague.”

The dress has the fashionable pointed bodice of the 1650s and the transparent gauzy scarf pinned at the neckline then at the height of fashion. While Mary was reportedly frustrated that as a widow she could not dance at parties, she did apparently enjoy dressing up in costume as a remarkable 1655 portrait (Fig. 4) records (Brown). The Royal Collection Trust explains: “It was perhaps painted to record the Princess’s appearance at an entertainment in The Hague early in 1655, where she appeared ‘very well dressed, like an Amazon.’”

The red feathered cloak was likely Brazilian in origin as Brazil was a Dutch colony at the time as the Trust details: “In the seventeenth century such cloaks were worn by Indians living in the North-East of Brazil.” The elaborately feathered and pearl-draped turban is likely intended to enhance the “exotic” character of the dress but has no known association with Brazil. The white satin dress she wears beneath the cloak closely resembles the one worn in the van Honthorst portrait discussed above (Fig. 7 above). She seems to have favored French fashions and visited Paris and her mother Henrietta Maria in 1656 to great success; according to Rebecca Starr Brown:

“Mary arrived decked out in her finest jewels and gowns, to the point that it garnered raised eyebrows from her mother, who stated her daughter ‘is not like me; she is very lofty with her ideas, with her jewels and her money. She likes splendour.’”

This seems somewhat disingenuous as Henrietta Maria had dressed quite splendidly in her time as queen [see “Fashion Icon” of 1630-1639].

Mary was only 24 and impressed the French with her beauty and fashionability; with one courtier remarking: “The Princess of Orange outshone all our ladies, although the Court was never more crowded with handsome women” (Brown).

She lived to see her brother Charles II restored to the throne and declared King of England, reuniting with him, her siblings and mother in London in 1660. Unfortunately, she contracted smallpox and died shortly after arriving in England at only age 29. Thus, she did not live to see her son Willem become William III, King of England, in the so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688 (which ousted her Catholic brother James II in favor of her Protestant son).

A posthumous portrait in 1664 depicted her yet again in her Brazilian feather cloak, but now with a black servant or slave with large pearl earring alongside her attaching a pearl bracelet to her wrist. There is no information as to the man’s identity, but he could be meant to represent the increasing Dutch presence in Africa, where they were heavily involved in the Atlantic slave trade. Sheldon Cheek, assistant director of the Image of the Black Archive & Library at Harvard University’s Hutchins Center, explains:

“Slavery was technically illegal in the Netherlands at this time, as it was throughout Europe, but the situation was still porous… Often, Africans would be brought into the Netherlands by means of the Dutch slave trade, presented as ‘gifts’ to the wealthy.” (Cook)

As the portrait was painted four years after her death, it’s not clear whether it reflects Mary’s actual household. While at the time he would have been seen merely as a sign of colonial success and as a fashionable accessory to the scene (see Fig. 12 above), today the man’s presence is a powerful reminder of the human suffering that made such fashionability and magnificence possible.

Fig. 1 - Gerard van Honthorst (Dutch, 1592-1656). Willem II (1626-50), Prince of Orange, and his wife Maria Stuart (1631-60), 1647. Oil on canvas; 302 x 194.3 cm (118.8 x 76.4 in). Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, SK-A-871. Source: Rijks

Fig. 2 - Gerard van Honthorst (Dutch, 1590-1656). Princess Mary Stuart, Princess of Orange (1631 - 1660), ca. 1640-80. Oil on panel; 73.7 x 59.1 cm (29 x 23 1/4 in). Berkshire: Ashdown House, NT 493052. Source: National Trust

Fig. 3 - Bartholomeus van der Helst (Dutch, 1613-1670). Mary Stuart, Princess of Orange, as Widow of William II, 1652. Oil on canvas; 199.5 x 170 cm. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, SK-A-142. Source: Rijksmuseum

Fig. 4 - Adriaen Hanneman (Dutch, c. 1604-71). Mary, Princess of Orange (1631-1660), 1655. Oil on canvas; 120 x 98 cm. London: Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 405877. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 5 - Adriaen Hanneman (Dutch, c. 1604-71). Posthumous Portrait of Mary I Stuart (1631- 1660) with a Servant, ca. 1664. Oil on canvas; 129.5 x 119.3 cm. The Hague: Mauritshuis, 429. Source: Mauritshuis

Menswear

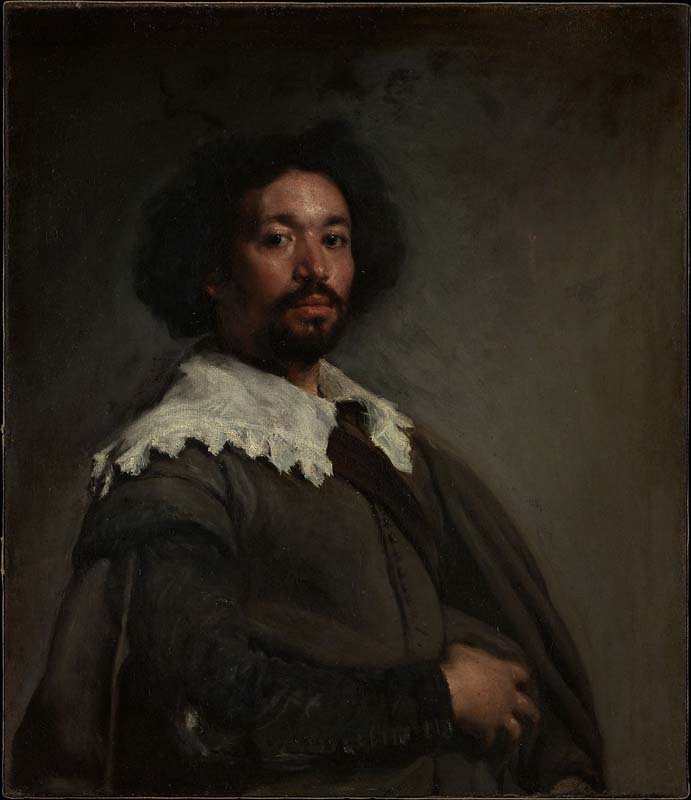

Juan de Pareja, Velázquez’s enslaved assistant (Fig. 1), wears the established fashions of the 1640s, which favored doublets closed with many small buttons, coordinating capes and large lace-edged collars. Yet in the 1650 portrait, the clothes are secondary to Pareja’s strong presence and dignified bearing. Pareja would be freed by Velázquez in 1654 and go on to have a successful painting career of his own. [For more on Pareja, see our analysis of the portrait, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s extensive catalogue entry on this painting or this YouTube video].

The foundation for menswear in the period would continue to be the linen shirt, paired with full breeches and typically topped with a doublet. We’re given a rare complete view of the shirt in Jan Steen’s portrait of the baker Arent Oostwaard (Fig. 2); as Davenport describes: “the Shirt, full and soft, is bloused over the breeches (which now hang unsupported on the hips)” (517).

Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie in his 1653 portrait (Fig. 3) shows the growing enthusiasm for ribbon loop decoration at the waist and along the bottom edges of the breeches. He has replaced the broad lace collar popular in earlier decades with a plain white linen band (collar) with the tasseled band strings hanging beneath his chin. He still wears the elaborate leather boots and boot hose that had been so characteristic of the 1640s.

A surviving black silk doublet, breeches and cape set (Fig. 4) worn by Karl X Gustav of Sweden shows a very similar pattern of decoration though the applied trim is black rather than gold metallic lace. Both looks feature a surfeit of gold ribbon loop decoration, however. Karl X Gustav’s breeches are the very wide, so-called petticoat breeches then popular. Boucher’s description of the look of the 1650s fits this surviving garment well:

“The doublet worn with these astonishing breeches was now only a sort of bolero, open in front and short enough for the full shirt… to show between the jacket and breeches. The very short doublet sleeves showed the shirt sleeves below. The entire costume was heavily loaded with small bows of ribbon.” (258)

Fig. 1 - Diego Velázquez (Spanish, 1599-1660). Juan de Pareja (1606–1670), 1650. Oil on canvas; 81.3 x 69.9 cm (32 x 27 1/2 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1971.86. Purchase, Fletcher and Rogers Funds, and Bequest of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot (1876-1967), by exchange, supplemented by gifts from friends of the Museum, 1971. Source: MET

Fig. 2 - Jan Steen (Dutch, 1626-1679). The Baker Arent Oostwaard and his Wife, Catharina Keizerswaard, 1658. Oil on panel; 38 x 32 cm (15 x 12 in). Amsterdam: Rijks Museum, SK-A-390. Source: Rijks Museum

Fig. 3 - Hendrick Munnichoven (Swedish, -1664). Portrait of Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie with his wife Maria Euphrosyne, 1653. Oil on canvas; 219 x 201 cm (86.2 x 79.1 in). Mariefred, Sweden: Gripsholm Castle. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (Swedish). Black silk robe coat, worn by Karl X Gustav of Sweden, 1658. Silk. Stockholm: Livrustkammaren, 19396 (3399: c). Source: LSH

Fig. 5 - Designer unknown (Swedish). Coronation suit worn by Karl X Gustav of Sweden, 1654. Gold embroidery. Stockholm: Livrustkammaren, T 4350. Source: LSH

The coronation suit of Karl X Gustav has a similar silhouette; as with the previous doublet, one can see that large open seams were favored in the sleeves where the shirt could then billow out. A matching embroidered baldrick (or sword hanger) resembles that worn by De la Gardie. Fellow Swede Emanuel De Geer (Fig. 6) shows that buff coats continued to be worn and demonstrates the enormous blousing effect the open seams permitted. De Geer also has the large ruffles at the shirt cuffs that were then typical, as Davenport describes: “below the short doublet sleeves, the shirt sleeve’s fullness, pushed up and tied in puffs, is finished at the wrist by a ruffle” (517). Notably he wears a knotted scarf at his neck, which resembles the cravat that will soon become fashionable.

The so-called “Spanish Clothing” worn by Karl X Gustav of Sweden emphasizes the richness of some menswear looks in this period. Here ribbon loops feature at both the waist and the breeches edge. As Cunnington remarks: “The amount of ribbon used for decorating was immense”; the Stapelton archive records in 1659 the purchase of “A suite and cloak of satin, trimmed with thirty-six yards of silver ribbon” (152).

Fig. 6 - Bartholomeus van der Helst (Dutch, 1613-1670). Emanuel De Geer, 1624-1692, 1656. Oil on canvas; 110 x 75 cm. Stockholm: Nationalmuseum, NMLeu 23. Source: NM

Fig. 7 - Design attributed to Fredrich Fewerbrün (Swedish). "Spanish Clothing", worn by Karl X Gustav of Sweden, 1654. Brown-gray cloth with gold and silver embroidery. Stockholm: Livrustkammaren, 24801 (3391). Source: LSH

Dress in England under Cromwell was more muted in palette, with black especially being favored. But the effect could still be luxurious as Oliver St John proves in his 1651 portrait (Fig. 8); his doublet has a dark golden sheen to it and gold and black striped ribbon loops adorn his breeches, hat and cape sleeves. Similarly, Walter Strickland (Fig. 9) wears a predominantly black look, this time with gold embroidery on the doublet, which has fashionably open seams allowing the shirt to be seen. He has discarded the leather boots still favored by St. John in favor of square-toed, high-heeled shoes with ribbon loop decoration. A similar pair of ribbon-adorned heeled shoes were worn by Karl X Gustav of Sweden (Fig. 10).

Fig. 8 - Pieter Nason (Dutch, 1612-1688). Oliver St John, 1651. Oil on canvas; 220 x 156.8 cm (86 5/8 x 61 3/4 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 4978. Source: NPG

Fig. 9 - Pieter Nason (Dutch, 1612-1688). Walter Strickland, 1651. Oil on canvas; 213.7 x 151.5 cm (84 1/4 x 59 5/8 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 5235. Source: NPG

Fig. 10 - Maker unknown (Swedish). Men's shoes, worn by Karl X Gustav of Sweden, 1650. Leather. Stockholm: Livrustkammaren, 27468 (06: 5903). Source: LSH

As Davenport describes and can be seen in the portrait of Strickland, shirt collars took on a recognizable shape in this period: “The collar hangs deep on the chest in an oblong which usually has rounded corners; it seldom lies quite flat and its tendency to buckle in the middle will become elaborated into gathered fullness.” (517) Frans Hals’ portrait of an unknown man (Fig. 11) depicts a more restrained version of the fashionable look of the day; here in more matte black, though with plenty of white shirt on view and pale pink and green ribbons at the waist. A surviving doublet in the Victoria & Albert Museum collection (Fig. 12) is flashier in its choice of materials but has the same cropped bolero style silhouette and open seams on the sleeves. Of the materials, the museum writes:

“The spectacular golden effect of the fabric of this example was created by weaving with silk and with threads wrapped with strips of silver gilt. This splendid material was probably imported from Italy, as there was little in the way of silk-weaving in Britain at this time. Adding to the luxurious effect is the lavish use of bobbin lace also made of silver-gilt thread.”

A 1659 portrait by Caspar Netscher (Fig. 13) nicely sums up fashionable dress for the decade with its large billowing shirt emerging from the sleeves, the short, open doublet, the ruffled cuffs, the ribbon loop decoration at waist and knees, and the adoption of heeled, square-toed shoes.

Fig. 11 - Frans Hals (Dutch, 1582/83-1666). Portrait of a Man, early 1650s. Oil on canvas; 110.5 x 86.4 cm (43 1/2 x 34 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 91.26.9. Marquand Collection, Gift of Henry G. Marquand, 1890. Source: MET

Fig. 12 - Designer unknown (British - woven in Italy). Doublet, 1650-1665. Silver-gilt silk tissue, trimmed with silver-gilt bobbin lace, lined with silk taffeta and reinforced with linen, hand-sewn with silk and linen thread. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.91-2003. Source: V&A

Fig. 13 - Caspar Netscher (Dutch, 1639-1684). Portrait of a Man, 1659. Oil on panel; 50.2 x 42.5 cm (19 3/4 x 16 3/4 in). Worcester, Massachusetts: Worcester Art Museum, 1955.56. Source: WAM

Extremely tightly spaced buttons were favored in this period as can be seen on a suit worn by Karl X Gustav of Sweden (Fig. 14), but also on the Jouers de tric-trac (Fig. 15). They also sport the round hats with broad brims (an evolution from earlier Cavalier-style hats) then popular, adorned, when possible, with a feather. While the player in black and observer in yellow are quite fashionable, the other men suggest how simpler versions of the day’s styles were adopted and how older styles continued to be worn among the working classes. [See the Children’s Wear section for a view of even humbler dress in the period.]

Fig. 14 - Designer unknown (Swedish). Suit, worn by Karl X Gustav of Sweden, 1650. Wool, silk. Stockholm: Livrustkammaren, 19033 (3420: b). Source: LSH

Fig. 15 - Le Nain brothers (French, 17th Century). Les joueurs de tric-trac, ca. 1655. Oil on canvas; 96 x 123 cm. Paris: Musée du Louvre. Source: Wikipedia

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Infants and toddlers were dressed predominately in white gowns, as seen in Nicolaes Maes Lacemaker (Fig. 1), as it made changing diapers and cleaning easier. The young child in the scene is also shown wearing a pudding cap, a padded helmet that protected the head while a child was learning to walk. The woman is shown making bobbin (or pillow) lace, which had edged collars in the first half of the century and would edge cravats in the second half—see it also on the doublet illustrated above (Fig. 12).

Slightly older children aged 3-6 of both sexes would continue to be dressed in gowns, though in styles that more closely reflected the fashions of the day and in a broader range of fabrics. Gerard ter Borch the Younger’s portrait of the Van Moerkerken family (Fig. 2) includes their young son in a gown with its front covered by an apron. The child’s hair is contained in a white cap that is then topped by a flat, black bonnet complete with ostrich feather and what appears to be metallic lace or ribbon.

At age 5 or 6 boys would be “breeched” and put into breeches like their fathers as seen in Jean Michelin’s Baker’s Cart (Fig. 3). From then on, boys and girls would be dressed as miniature adults.

Fig. 1 - Nicolaes Maes (Dutch, 1634–1693). The Lacemaker, ca. 1656. Oil on canvas; 45.1 x 52.7 cm (17 3/4 x 20 3/4 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 32.100.5. The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931. Source: MET

Fig. 2 - Gerard ter Borch the Younger (Dutch, 1617–1681). The Van Moerkerken Family, ca. 1653–54. Oil on wood; 41.3 x 35.6 cm (16 1/4 x 14 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982.60.30. The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection, 1982. Source: MET

Fig. 3 - Jean Michelin (French, ca. 1616–1670). The Baker's Cart, 1656. Oil on canvas; 98.4 x 125.4 cm (38 3/4 x 49 3/8 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 27.59. Fletcher Fund, 1927. Source: MET

References:

- “Adriaen Hanneman (1604-71) – Mary, Princess of Orange (1631-1660).” Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.rct.uk/collection/405877/mary-princess-of-orange-1631-1660.

- Boucher, François, Yvonne Deslandres, and John Ross. A History of Costume in the West. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/443676264.

- Brown, Rebecca Starr Brown. “The First English Princess of Orange.” Rebecca Starr Brown (blog), March 14, 2017. https://rebeccastarrbrown.com/2017/03/14/the-first-english-princess-of-orange/.

- Cook, Greg. “Were Those Black ‘Servants’ In Dutch Old Master Paintings Actually Slaves?” Accessed June 23, 2020. https://www.wbur.org/artery/2016/01/15/black-servants-old-master-art-slavery.

- Cumming, Valerie. A Visual History of Costume: The Seventeenth Century. 3. London: Batsford, 1984. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/9761398.

- Cunnington, C. Willett, and Phillis Emily Cunnington. Handbook of English Costume in the Seventeenth Century. Boston: Plays, Inc, 1972. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/755269282.

- Davenport, Millia. The Book of Costume. New York: Crown Publishers, 1948. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/922657048.

- V and A Collections. “Doublet | V&A Search the Collections,” June 24, 2020. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O85964.

- Hill, Daniel Delis. History of World Costume and Fashion. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/768100950.

- “Mary, Princess Royal and Princess of Orange – National Portrait Gallery.” Accessed June 23, 2020. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp03000/mary-princess-royal-and-princess-of-orange.

- Rijksmuseum. “Mary Stuart, Princess of Orange, as Widow of William II, Bartholomeus van Der Helst, 1652.” Accessed June 23, 2020. https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/SK-A-142.

- Mould, Philip. “Mary, the Princess Royal | Studio of Gerrit van Honthorst.” Philip Mould. Accessed June 23, 2020. http://www.historicalportraits.com/Gallery.asp?Page=Item&ItemID=2254&Desc=Mary,-the-Princess-Royal-|-Studio-of-Gerrit-van-Honthorst.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Sir Peter Lely (Pieter van Der Faes) | Mary Capel (1630–1715), Later Duchess of Beaufort, and Her Sister Elizabeth (1633–1678), Countess of Carnarvon | The Met.” Accessed June 23, 2020. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436871.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Velázquez (Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez) | Juan de Pareja (1606–1670) | The Met.” Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437869.

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1650-1659

Rulers:

- England

- Oliver Cromwell (1653-1658)

- Richard Cromwell (1658-1659)

- France: Louis XIV (1643-1715)

- Spain: Philip IV (1621-1665)

Europe, 1650. Source: Pinterest

Events:

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Primary/Period Sources

Secondary Sources

Also see the 17th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.