OVERVIEW

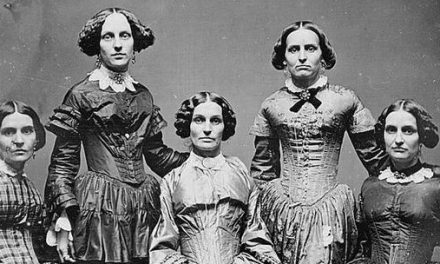

The beginning of 1871 saw a brief pause in fashion change due to the Franco-Prussian War and Paris Commune. The bustle (or tournure) with a half-train was the most desirable silhouette, often paired with a tablier, or apron-fronted skirt.

Womenswear

A January “New York Fashions” column in Harper’s Bazar, subtitled “Change of Styles,” carefully outlined changes between the fashions of 1870 and 1871:

“Although we have had no radical change of fashions within a year, the most casual observer must perceive a difference between the costumes of last winter and of the present. The dashing ‘girl of the period’ styles have passed away, and we have in their stead more quiet, refined dressing, suitable for dignified women, yet not too demure for the most youthful. In lieu of costumes made up of colors in violent contrast, we now have shades of one color pervading the suit; the Grecian-bend panier, with its unsightly puff, has given place to a modest tournure and graceful drapery; towering chignons of false hair are supplanted by natural braids that disclose the contour of the head; plump, healthy-looking waists are preferred to waspish ones; instead of skirts ankle short for promenading, we have more graceful ones just clearing the ground, while voluminous trains are discarded for the more sensible half-train; high, curved, French heels are positively outré, and the jaunty jockey hat, with its defiant aigrette, is gradually receding before the demure-looking gipsy bonnet. The last-mentioned change we regret somewhat, but we congratulate our readers on the tasteful, sensible, and lady-like ensemble that a fashionable dressed woman now presents. There is scarcely a target left at which critics can aim their arrows of malice.” (35)

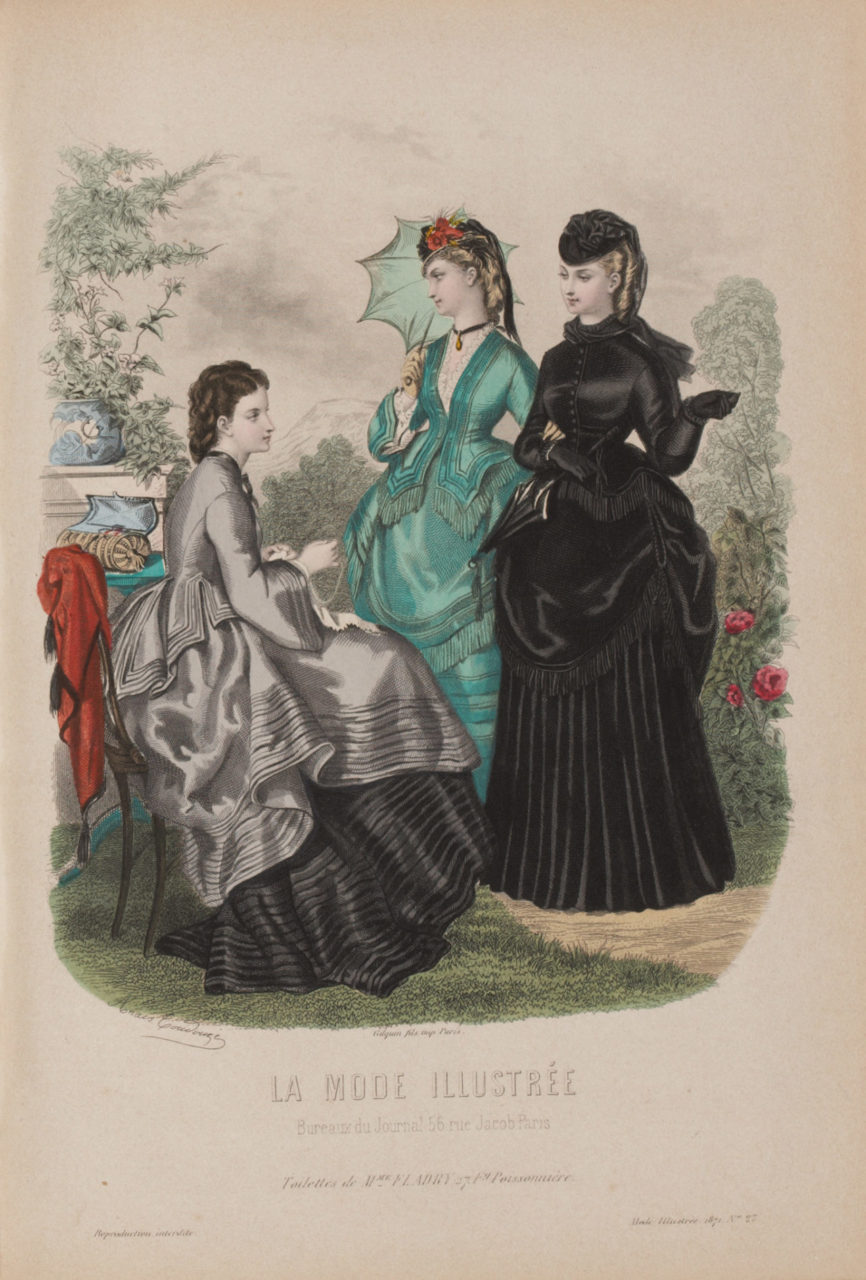

This helpful summary notably makes no reference to the current state of affairs in France, where most French fashion magazines ceased to publish during the Franco-Prussian War, only resuming in April 1871, only to again be interrupted by the outbreak of the Paris Commune. When they finally returned, plates illustrating full mourning dress, rare before the war, were seen in French magazines and their allied publishers in other countries (Figs. 1-2).

Fashion journals in other countries that depended on Paris for fashion innovation and color plates improvised solutions and reported on what news there was. American periodical Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine reported in March 1871, for example: “The new color for winter is a rich shade of red, which, in spite of its repulsive name, sang de Prusse, promises to become very popular” (200). Sang de Prusse (Fig. 3) literally means “blood of the Prussian,” a frightful name, but an unsurprising one given the political circumstances and the tendency to name new colors after contemporary events–magenta takes its name from a bloody battle in Magenta, Italy, for example (Tétart-Vittu 272).

Fig. 1 - E. Preval (French). The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine, (1871): pl. 1014. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 2 - Adèle-Anaïs Toudouze (French, 1822-1899). La Mode illustrée, no. 27 (January 8, 1871). Source: Bunka Gakuen Library

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown. Victoria, (February 1871). Source: Pinterest

Fig. 4 - Édouard Manet (French, 1832–1883). Repose, ca. 1871. Oil on canvas; 148 x 113 cm (59 1/8 x 44 7/8 in). Providence: Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, 59.027. Bequest of Mrs. Edith Stuyvesant Vanderbilt Gerry. Source: RISD Museum

Fig. 5 - William Notman (Scottish-Canadian, 1826-1891). Mlle Fanshawe, Montréal, QC, 1871. Albumen print; 17.8 x 12.7 cm. Montreal: Musée McCord, I-68103.1. Achat de l'Associated Screen News Ltd. Source: Musée McCord

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (European). Afternoon dress, ca. 1871. Cotton. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.38.23.247a–d. Gift of Lee Simonson, 1938. Source: The Met

Fig. 7 - A. Lacourieux? (French). Mode di Parigi, December 1871. Source: Pinterest

The British journal World of Fashion thought the war had improved fashion, writing in February 1871:

“In our opinion indeed, the taste in Fashion has been purer and more really elegant, than it would have been if some of the leaders of Parisian Fashion had reigned at the present time. There has been a cessation of that extreme extravagance, both in style and costliness, which has so often formed the subject of remark” (1).

World of Fashion was not afraid to give England the credit for this improvement, remarking that their French fashion plate artists—temporarily relocated to London—“since their arrival in England have acquired a purer taste, and we have no doubt that there will be a great reform, and that Fashion will now become all that can be desired” (1). Similar hopes for the renewal and reformation of fashion were also expressed in French fashion journals after the war.

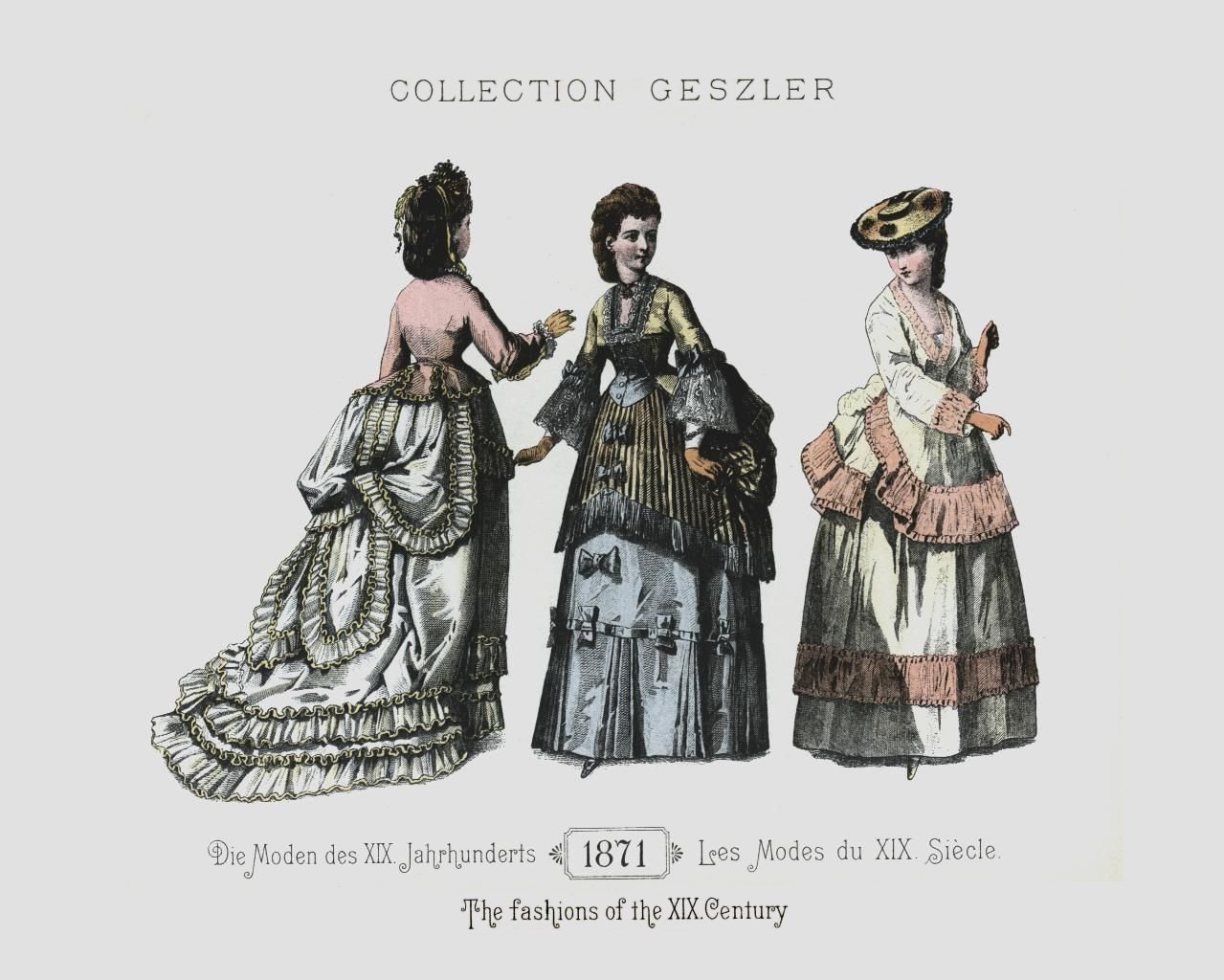

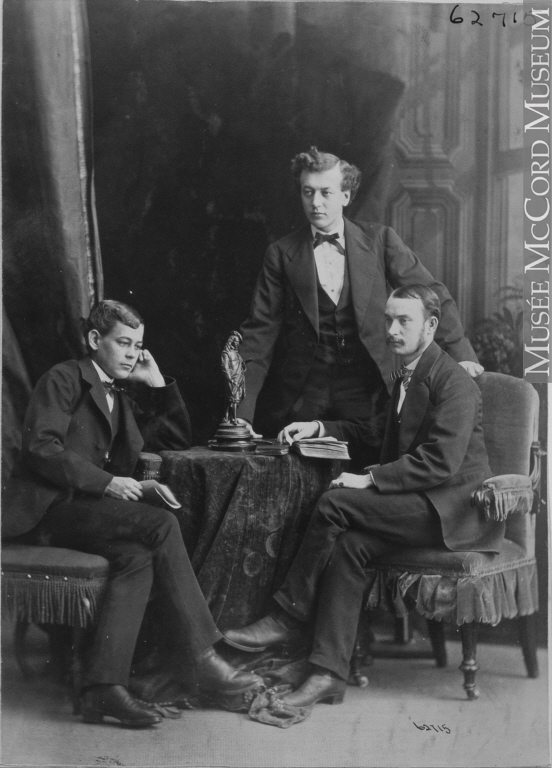

This desire led to an attempt at simplicity in dress (Figs. 4-8) and a great deal of continuity with the prior year’s styles. Monochromatic styles were embraced and the overall silhouette continued to move towards a bustled profile with a modest train (Figs. 5-8). Given the disruption of the Paris Commune, which saw women take up arms in the streets of Paris, there was also a strong emphasis on domesticity and femininity in 1871 styles. Tablier, or apron-front, gowns became especially popular (Figs. 6, 9-10), with Harper’s Bazar commenting in June: “Coquettish little aprons of various materials from Swiss muslin to black silk, now form part of afternoon costumes for the house… the whole tablier is so elaborately trimmed with ruffles, lace, and passementerie that it becomes an ornament for almost any dress” (371).

Fig. 10 - Michele Gordigiani (Italian, 1835-1909). Maria von Berg, 1871. St. Petersburg: Hermitage. Source: Athenaeum

Fig. 11 - Isabelle Toudouze (French, 1850-1907). Magasin des Demoiselles, (September 10, 1871). Source: Pinterest

Fig. 12 - William Notman (Scottish-Canadian, 1826-1891). Miss Dolton, Montreal, QC, 1871. Albumen print; 17.8 x 12.7 cm. Montreal: Musée McCord, I-63890.1. Source: Musée McCord

Fig. 13 - Designer unknown. Light purple silk fringed dress, 1871. Bath: Fashion Museum. Source: Fashion Museum, Bath

Skirts with multiple flounces and trimmings of lace and fringe were frequently seen (Figs. 11-16). A September 1871 column in the British periodical Bow Bells notes an enthusiasm for bright colors and lace flounces: “Satins of the brightest hues, deeply trained and covered with flounced muslin or lace robes…” (139).

Jules Elie Delaunay’s 1871 Portrait of Madame Mestayer (Fig. 14) embodies many of the trends of the day in its restrained color palette—black, with only touches of pink—and yet emphasis on femininity—with bows, ruffles and lace as accents. A dress with a similar neckline and restrained simplicity can be seen in Fig. 7. This deft navigation of the fraught fashion landscape after the Franco-Prussian War and Paris Commune befits Mme Mestayer’s status as “wife of the president of the Nantes Museum board… [and] a close friend of Delaunay and [fashionable painter Auguste] Toulmouche and a cultivated woman whose salon was frequented the city’s intellectuals” (Sciama).

Fig. 14 - Jules Elie Delaunay (French, 1828-1891). Portrait of Madame Mestayer, 1871. Oil on canvas; 78 x 64 cm. Inv. 2270. Mestayer Bequest, 1940. Source: Jules Elie Delaunay

Fig. 15 - Collection Geszler. 1871. Published 1898. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 16 - Héloïse Colin (French, 1819-1873). The Young Ladies' Journal, no. 92 (September 1, 1871). Source: Pinterest

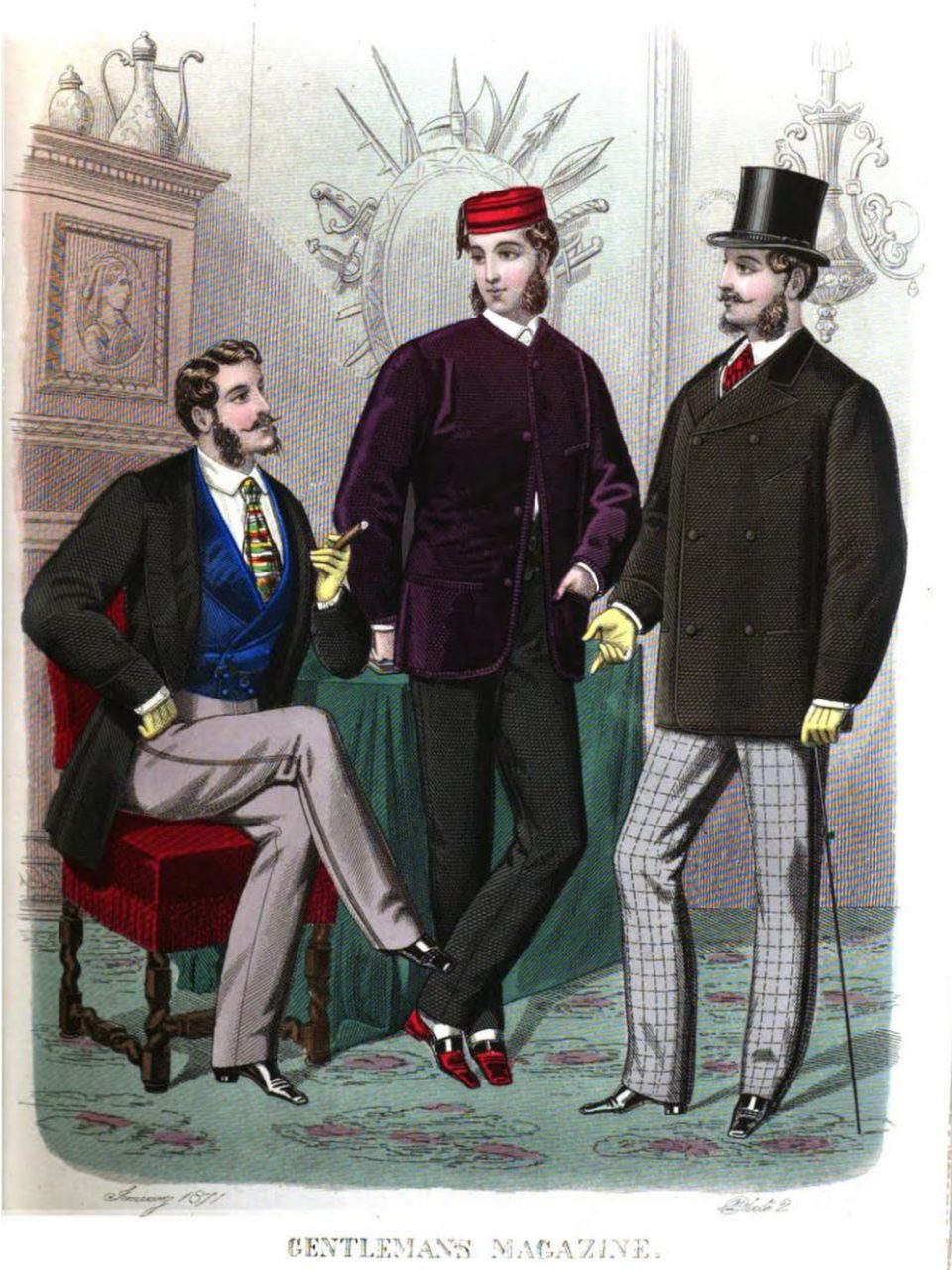

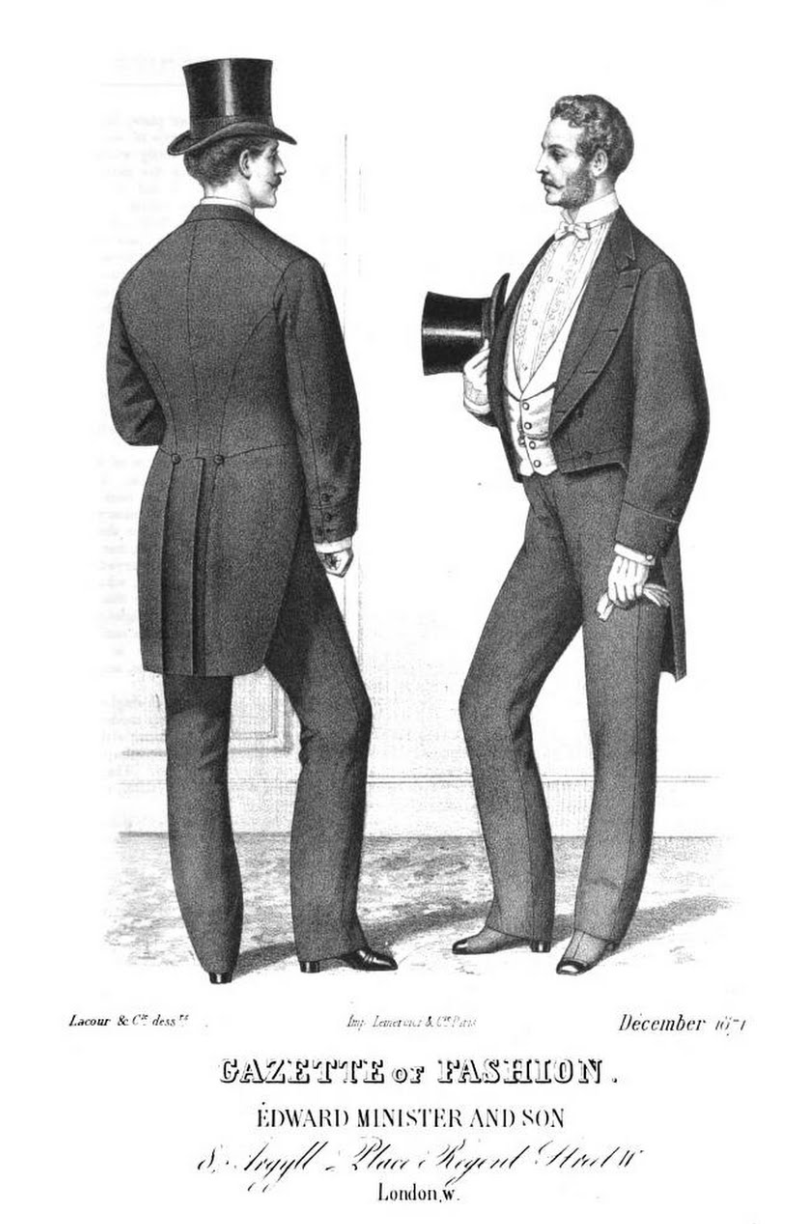

Menswear

[To come…]

Fig. 1 - Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917). Jeantaud, Linet and Laine, 1871. Oil on canvas; 38 × 46 cm. Paris: Musée d'Orsay, RF 2825. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 2 - William Notman (Scottish-Canadian, 1826-1891). Le groupe de D. J. Edwards, Montréal, QC, 1871. Albumen print. Montreal: Musée McCord, I-62715.1. Source: Musée McCord

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown. Gentleman's Magazine of Fashion, vol. 23, no. 265 (January 1871): pl. 2. Source: Google Books

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown. Gazette of Fashion, vol. 26, no. 308 (December 1, 1871). Source: Google Books

Fig. 5 - Maker unknown (Irish). Double-breasted frock coat, 1871. Fine wool; 97 cm chest, length: 88 cm overall. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.47-1947. Given by Mr A. W. Furlong. Source: V&A

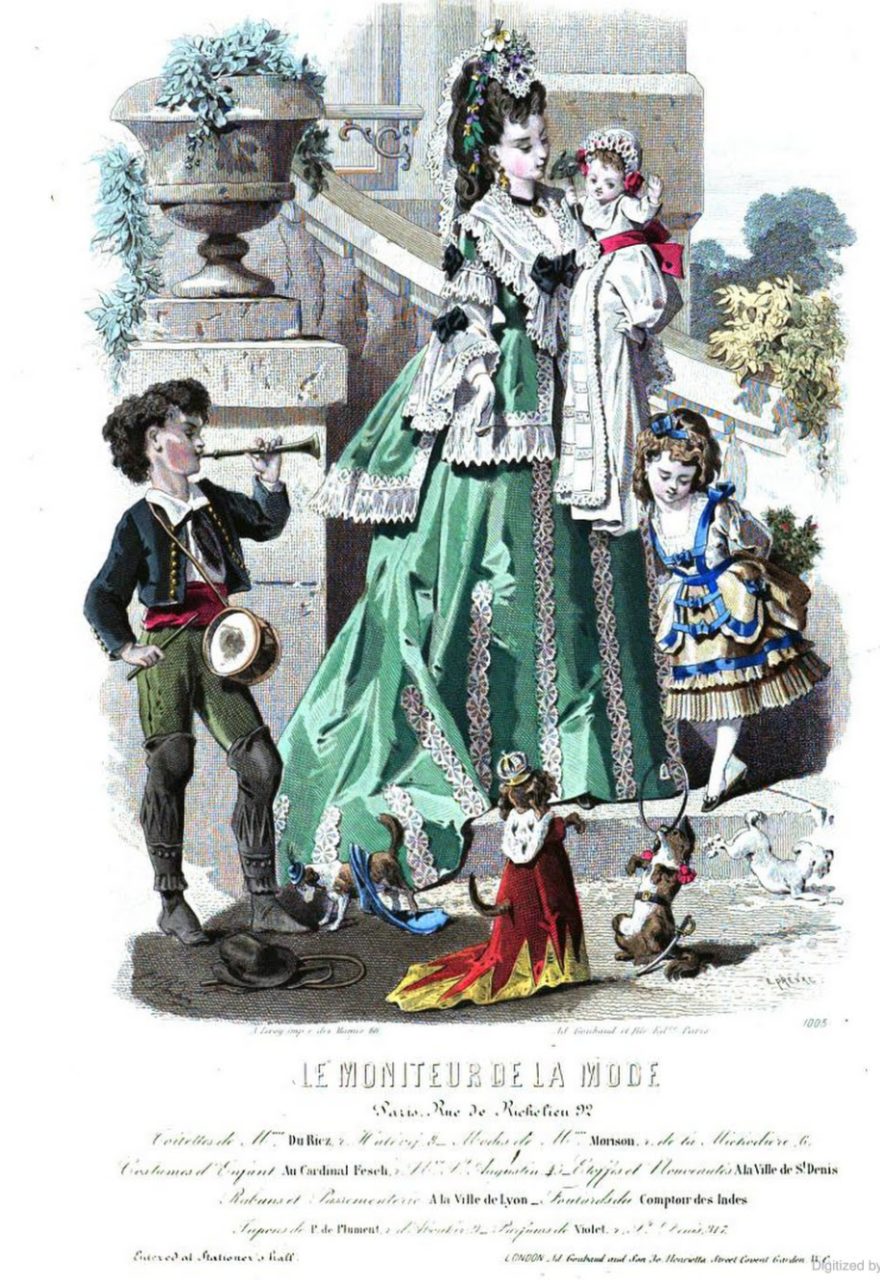

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Fig. 1 - Eduardo Rosales Gallinas (Spanish, 1836-1873). Concepción Serrano, later Countess of Santovenia, 1871. Oil on canvas; 163 x 106 cm. Madrid: Museo del Prado, P06711. Source: Prado

Fig. 2 - Dallinger, Modes, Richmond (British). Dress, ca. 1871. Silk, cotton. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1983.93.3a–c. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Trust Gift, 1983. Source: The Met

Fig. 3 - Photographer unknown (German). Carte de visite, ca. 1871. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 4 - A. Bodin? (French). Moniteur de la mode, (August 1871): pl. 1005. Source: Google Books

References:

- “Central Europe and Low Countries, 1800–1900 A.D.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. Accessed January 31, 2017. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/?period=10®ion=euwc (October 2004)

- “Fashions by Balloon.” Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine LXXXII, no. 13 (March 1871): 200. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=chi.16293935;view=1up;seq=192

- “Fashions for September.” Bow Bells XV, no. 370 (August 30, 1871): 139. https://books.google.com/books?id=hD8lAQAAMAAJ

- “New York Fashions.” Harper’s Bazar IV, no. 3 (January 21, 1871): 35. https://books.google.com/books?id=lKoxAQAAMAAJ

- “New York Fashions.” Harper’s Bazar IV, no. 24 (June 17, 1871): 371. https://books.google.com/books?id=lKoxAQAAMAAJ

- “Observations on London and Parisian Fashions.” The World of Fashion 48, no. 555 (February 1871): 1. https://books.google.com/books?id=rBwGAAAAQAAJ

- Sciama, Cyrille. “Madame Mestayer.” Jules-Elie Delaunay – Musée des Beaux Arts de Nantes. Accessed February 17, 2017. http://www.jules-elie-delaunay.fr/en/7-portraits/19-madame-mestayer

- Tétart-Vittu, Françoise, and Gloria Groom. “Key Dates in Fashion and Commerce, 1851-89.” In Impressionism, Fashion, & Modernity, ed. Gloria Groom, 270-79. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012.

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1871

Rulers:

- America

- President Ulysses S. Grant (1869-77)

- England: Queen Victoria (1837-1901)

- France

- Paris Commune (1871)

- Third Republic: President Adolphe Thiers (1871-73)

- Spain

- Regent: Francisco Serrano y Domínguez (1868-71)

- King Amadeo I (1871-73)

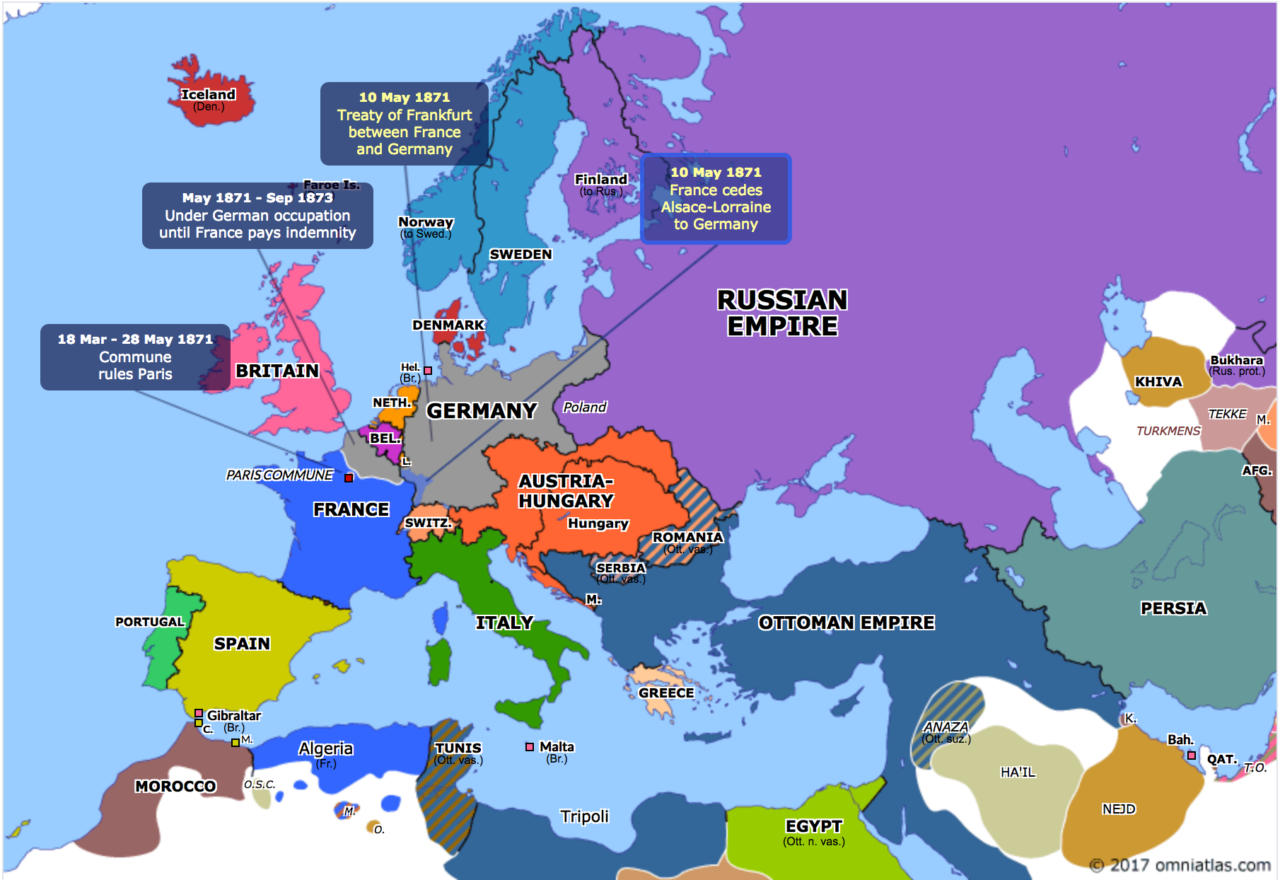

Treaty of Frankfurt, 1871. Source: Omniatlas

Events:

- 1870-71 – Prussians besiege Paris

- “During the siege of Paris, many designers, including Worth and Madame Maugas, organize ambulances for the men protecting the city. Department stores remain open, but some, like Les Grands Magasins du Louvre (located on the Rue de Rivoli) and Pygmalion (on the rue Saint-Denis) are damaged by fires.” (IFM 274)

- “Prussia defeats France in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), instigated by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898) with the aim of a unified Germany. Bismarck triumphs, and William I, king of Prussia (r. 1861–88), is crowned emperor of Germany (r. 1871–88) in the same year. As a result of the war, Germany gains the greater part of former French territories Alsace and Lorraine.” (The MET)

- March 26 – The Paris Commune is formally established in Paris.

- May 30 – French Third Republic: Government suppression of the Paris Commune rebellion is completed.

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Fashion Plate Collections (Digitized)

- Costume Institute Fashion Plate collection

- Casey Fashion Plates (LA Public Library) - search for the year that interests you

- New York Public Library:

NYC-Area Special Collections of Fashion Periodicals/Plates

- FIT Special Collections (to make an appointment, click here)

- Costume Institute/Watson Library @ the Met (register here)

- Journal des demoiselles, 1870-79 (AP20 .J76 RARE BOOK)

- La Mode illustrée, 1870-79 (AP21.A3 M6 Q)

- New York Public Library

- Brooklyn Museum Library (email for access)

Womenswear Periodicals (Digitized)

Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Menswear Periodicals / Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Secondary Sources

Also see the 19th-century overview page for more research sources... or browse our Zotero library.