OVERVIEW

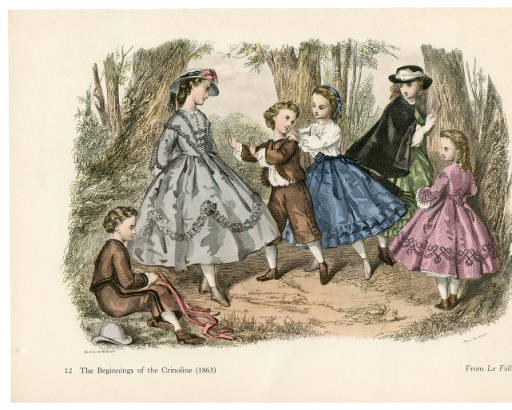

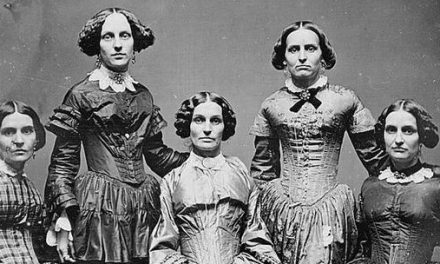

1863 saw the crinoline still reigning triumphant with full bell-shaped skirts and tiny, nipped-in corseted waists the ideal silhouette—in part due to the support of the French Empress Eugénie. In more avant-garde circles, some were beginning to abandon the crinoline.

Womenswear

E

uropean fashion during the 1860s is distinguished by small waists, achieved with corsets, and fuller “bell” skirts. The shapes of these skirts are attained through the use of crinolines and hoops (Wikipedia).

An 1863 “Chitchat Upon New York and Philadelphia Fashions for March” column in Godey’s Lady’s Book emphasized the prominence of the crinoline in 1860s fashion:

“Crinoline reigns triumphant, and, consequently, skirts are still worn very full. The back breadths are faced with a patent lining, a stiff material to be had of all colors, and which causes the dress to spread very gracefully. The newest hoops which we have seen are from Mme. Demorset’s. They are gored, very wide at the bottom, tapering to the waist, so small, indeed, that the hoops fit closely to the figure. Many of the hoops are covered with a white or colored case, on which is buttoned a deep flounce, which may be changed to a white or colored one, as the weather may permit. By adopting this method, a lady may always well jorponèe [sic].” (317)

A Peterson’s Magazine 1863 editorial subtitled “Will Crinoline Last?” remarks that the fall of the crinoline is often predicted, but is never realized. They emphasized that Empress Eugenie’s role in setting fashion:

“The Empress of the French protects it, and it remains fashionable. The Countess Walewski, notwithstanding, appeared at a court ball last month without any crinoline whatever; but that is not sufficient to dethrone it, the example must be set by the Empress Eugenie herself; she it was who made the fashion, and she is not likely to abandon it.” (473)

The column goes on to praise the crinoline, remarking that it “adds dignity to the figure, causes the waist to look smaller, and gives grace to many women, who would look awkward without it” (473).

Fig. 1 - Designer unknown (American). Dress, 1860-1865. Silk, mother-of-pearl. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.69.33.4a–d. Gift of Mary Pierrepont Beckwith, 1969. Source: The Met

Fig. 2 - William Notman (Canadian, 1826-1891). Mrs. Thomas Hodgins, Montreal, QC, 1863, 1863. Silver salts on paper mounted on paper - albumen process; 8 x 5 cm. Montreal: McCord Museum, I-8187.1. Purchase from Associated Screen News Ltd. Source: McCord Museum

Fig. 3 - William Notman (Canadian, 1826-1891). Mrs. D. C. Taylor, Montreal, QC, 1863, 1863. Silver salts on paper mounted on paper - albumen process; 8.5 x 5.6 cm. Montreal: McCord Museum, I-8452.1. Purchase from Associated Screen News Ltd. Source: McCord Museum

Fig. 4 - Jules David (French, 1808-1892). Le Moniteur de la Mode, March 1863. Source: The Bartos Collection

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown. Godey's Fashions For February 1863, 1863. Print; 21 x 29 cm (8 x 11 1/4 in). New York: The New York Public Library Digital Collections. Source: NYPL

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (American). Morning dress, early 1860s. Cotton. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.60.6.10. Gift of Chauncey Stillman, 1960. Source: The Met

E

uropean day dresses displayed wide pagoda sleeves worn over under sleeves or engageantes (Wikipedia) (Fig. 5). Another notable sleeve style in the 1860s was the bishop sleeve, which is simply the gathering of the full pagoda sleeve into a decorated cuff (Fig. 2). Daywear featured high necklines and are usually emphasized with lace or tatted collars or chemisettes, achieving a demure look (Wikipedia) (Fig. 5). Daywear ensembles also come with matching mantles and cloaks, to be worn outdoors (Fig. 4).

An April 1863 “Fashions” column in The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine noted:

“A great variety is likely to prevail in Mantles and Cloaks this year. The scarf-shaped mantilla will once more be in favour, together with the collets, or round capes, the tight-fitting casaques, and the small saute-en-barques, so much preferred last summer. The shape of these last-named garments is to be slightly modified; the seams will be taken in a little, so that the cloak may fit somewhat closer to the waist, which will certainly be a great improvement, as the very loose saute-en-barque had a very ungraceful appearance, entirely hiding the figure.” (284)

This article further notes that garments that emphasize the figure are ideal. In contrast to the daywear ensembles, evening gowns were much more revealing and had low off-the-shoulder necklines and short sleeves, and were accessorized with short gloves or lace or crocheted finger-less mitts (Wikipedia) (Fig. 7-12).

A January “Fashions” column in The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine 1863, classified the different materials used for evening gowns:

“The material for ball dresses may be classified under two heads: rich and costly silk for the middle-aged matron [Fig. 9], and the light, airy fabrics for young ladies, both married and single [Fig. 7].” (140)

Dresses in the 1860s, both daywear and evening, were embellished with ruffles, pleats, and scallops. Hairstyles during the 1860s often featured a part in the middle. Hair was usually smoothed or waved over the ears. The ends of the hair was worn pinned in a bun or roll. To keep hair in place, braids are used and then pinned in varied fashions to the head. Occasionally, a few curls dangled behind the neck. Holding the hair in place was usually achieved using hair oils and pomades (Wikipedia) (Fig. 3, 9).

Bonnets were prevalent as a hair accessory during the 1860s (Fig. 4).

As for the fashionability of Franz Xaver Winterhalter’s portrait of Marie Henriette (Fig. 7). It is safe to say that her evening ensemble is within the acceptable parameters of fashion at that time. The most telling detail that classifies it as “fashionable” is the silhouette of the dress, with its slim waist and full skirt, achieved with a corset and a crinoline. The exposure of the décolleté are is also considered fashionable during the 1860s. The color and material too, falls within fashionable propriety, emphasizing her youth with white and the lightness of the fabric used.

Fig. 7 - Franz Xaver Winterhalter (German, 1805-1873). Marie-Henriette, Duchesse de Brabant (1836-1902), née Archduchess of Austria, Princess Palatine of Hungary, 1863. Oil on canvas; 157 cm x 106 cm (62 x 42 in). Laeken: Royal Collection, Castle of Laeken. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 8 - Franz Xaver Winterhalter (German, 1805-1873). Portrait of Lady Middleton, 1863. Oil on canvas; 239 x 147.5 cm. Private Collection. Source: Wiki Art

Fig. 9 - Franz Xaver Winterhalter (German, 1805-1873). Portrait of Queen Sophie of Netherlands, Born Sophie of Württemberg, 1863. Oil on canvas. Private Collection. Source: Wiki Art

Fig. 10 - Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910). Madame Camille Silvy, ca. 1863. Albumen silver print; 8.9 × 6 cm (3 1/2 × 2 3/8 in). Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 93.XD.29.2. Gift in memory of Madame Camille Silvy born Alice Monnier from the Monnier Family. Source: Getty

Fig. 11 - Artist unknown. Woman In Bridal Gown And Women In Formal dress, 1863. Print; 20 x 27 cm (7 3/4 x 10 1/2 in). New York: The New York Public Library Digital Collections. Source: NYPL

Fig. 12 - Designer unknown (French). Wedding ensemble, 1864. Cotton. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 26.250.2a–e. Gift of Mrs. James Sullivan, in memory of Mrs. Luman Reed, 1926. Source: The Met

Menswear

[To come…]

Fig. 1 - Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910). Self-portrait, about 1863. Albumen silver print, card photograph; 8.6 × 5.7 cm (3 3/8 × 2 1/4 in). Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 93.XD.29.1. Gift in memory of Madame Camille Silvy born Alice Monnier from the Monnier Family. Source: Getty

Fig. 2 - Edouard Manet (French, 1832-1883). Luncheon on the Grass, 1863. Oil on canvas; 208 x 264.5 cm. Paris: Musée d'Orsay. Etienne Moreau Nélaton donation, 1906. Source: Musée d'Orsay

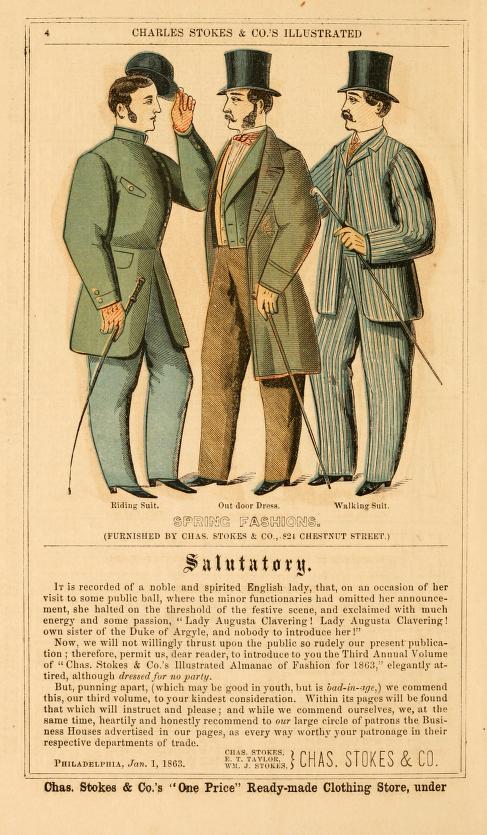

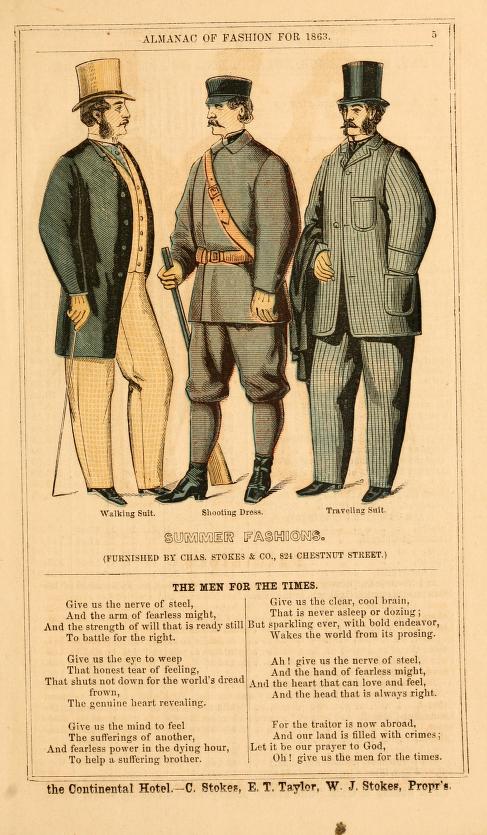

Fig. 3 - Charles Stokes & Co. (Philadelphia) (American). Illustrated almanac of fashion, 1863. Winterthur: Winterthur Museum Library. Source: US National Archive

Fig. 4 - Charles Stokes & Co. (Philadelphia) (American). Illustrated almanac of fashion, 1863. Winterthur: Winterthur Museum Library. Source: US National Archive

Fig. 5 - A. P. Rego (Portuguese). Military uniform, ca. 1863. Woll, metal, leather. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.2453a–e. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mrs. William Reeves, 1957. Source: The Met

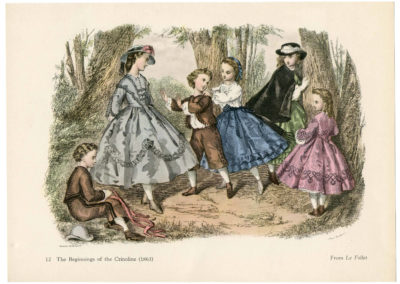

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Fig. 1 - Designer unknown (American). Dress, 1860–69. Cotton. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.934. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of The Jason and Peggy Westerfield Collection, 1969. Source: The Met

Fig. 2 - Myron H. Kimball (American). Rebecca, Charley and Rosa, Slave Children from New Orleans, 1863-64. Albumen silver print from glass negative; 8.4 x 5.4 cm (3 5/16 x 2 1/8 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011.478. The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Fund, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2011. Source: The Met

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown. Children 1860-1864, Plate 064, 1860-64. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17509853. Gift of Woodman Thompson. Source: The Met

Fig. 4 - William-Adolphe Bouguereau (French, 1825-1905). Portrait of Mlle Brissac, 1863. Oil on canvas; 91 x 71 cm. Private Collection. Source: Wiki Art

References:

- “1860s in Western fashion,” Wikipedia, accessed March 2017, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=1860s_in_Western_fashion&oldid=769002916

- “Chitchat Upon New York and Philadelphia Fashions for March.” Godey’s Lady’s Magazine 66-67 (1863): 317. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015020057520;view=1up;seq=317

- “Editorial Chit-Chat: Will Crinoline Last?”. Peterson’s Magazine 43-44 (January-June 1863): 473. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101076519949;view=1up;seq=485

- “Fashions.” The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine 6, no. 33 (Jan. 1863): 141. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015022690567;view=2up;seq=454

- “Fashions.” The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine 6, no. 36 (Apr. 1863): 284. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015022690567;view=2up;seq=604

- Tétart-Vittu, Françoise, and Gloria Groom.”Key Dates in Fashion and Commerce, 1851–89″. Impressionism, Fashion and Modernity, ed. Gloria Groom. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012.

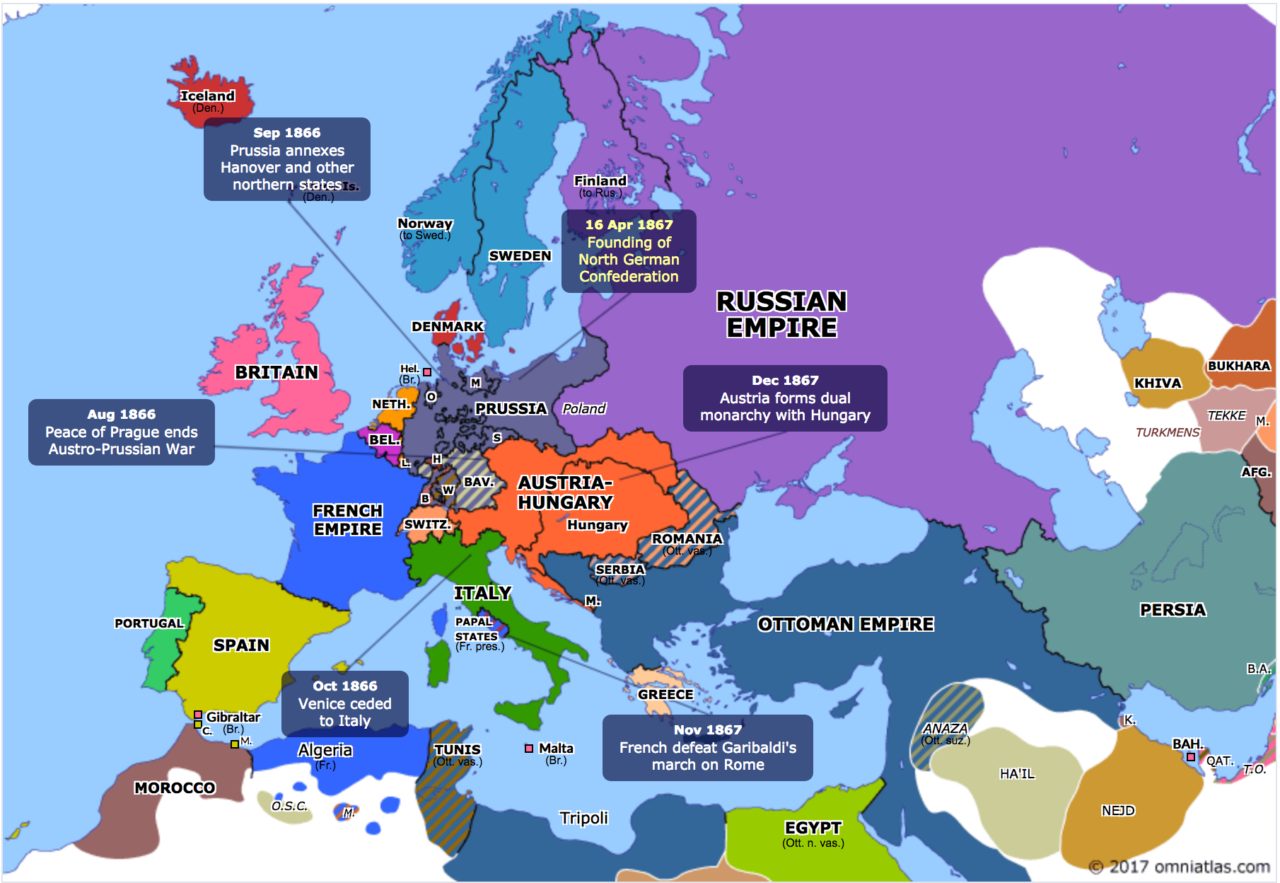

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1863

Rulers:

- America:

- President Abraham Lincoln (1861-65)

- England: Queen Victoria (1837-1901)

- France

- Emperor Napoleon III (1852-70)

- Spain

- Queen Isabel II (1833-68)

Europe 1867. Source: Omniatlas

Events:

- 1863 – Salon des refusés in Paris

- The department store Au Louvre is renamed Les Grands Magasins du Louvre (Tétart-Vittu 273).

- First listing of the couturier Émile Pingat (1820–1901) in the Bottin du commerce. A rival to Worth as a designer and as a tastemaker, the dressmaker Pingat, also specializes in outerwear, such as opera coats, jackets, and mantles (Tétart-Vittu 273).

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Fashion Plate Collections (Digitized)

- Costume Institute Fashion Plate collection

- Casey Fashion Plates (LA Public Library) - search for the year that interests you

- New York Public Library:

NYC-Area Special Collections of Fashion Periodicals/Plates

- FIT Special Collections (to make an appointment, click here)

- Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine (London: 1852-79), 1860-64, 1867-69 (TT500 .E6)

- Costume Institute/Watson Library @ the Met (register here)

- New York Public Library

- Brooklyn Museum Library (email for access)

Womenswear Periodicals (Digitized)

Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Menswear Periodicals / Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Secondary Sources

Also see the 19th-century overview page for more research sources... or browse our Zotero library.